Framework for the development and evaluation of complex interventions: gap analysis, workshop and consultation-informed update

Affiliations.

- 1 Medical Research Council/Chief Scientist Office Social and Public Health Sciences Unit, Institute of Health and Wellbeing, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK.

- 2 Medical Research Council Lifecourse Epidemiology Unit, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK.

- 3 Medical Research Council ConDuCT-II Hub for Trials Methodology Research and Bristol Biomedical Research Centre, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK.

- 4 Health Economics and Health Technology Assessment Unit, Institute of Health and Wellbeing, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK.

- 5 Public Health Scotland, Glasgow, UK.

- 6 Manchester Centre for Health Psychology, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK.

- 7 London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK.

- 8 Faculty of Health and Medicine, Lancaster University, Lancaster, UK.

- 9 Medical Research Council Epidemiology Unit, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK.

- PMID: 34590577

- PMCID: PMC7614019

- DOI: 10.3310/hta25570

Background: The Medical Research Council published the second edition of its framework in 2006 on developing and evaluating complex interventions. Since then, there have been considerable developments in the field of complex intervention research. The objective of this project was to update the framework in the light of these developments. The framework aims to help research teams prioritise research questions and design, and conduct research with an appropriate choice of methods, rather than to provide detailed guidance on the use of specific methods.

Methods: There were four stages to the update: (1) gap analysis to identify developments in the methods and practice since the previous framework was published; (2) an expert workshop of 36 participants to discuss the topics identified in the gap analysis; (3) an open consultation process to seek comments on a first draft of the new framework; and (4) findings from the previous stages were used to redraft the framework, and final expert review was obtained. The process was overseen by a Scientific Advisory Group representing the range of relevant National Institute for Health Research and Medical Research Council research investments.

Results: Key changes to the previous framework include (1) an updated definition of complex interventions, highlighting the dynamic relationship between the intervention and its context; (2) an emphasis on the use of diverse research perspectives: efficacy, effectiveness, theory-based and systems perspectives; (3) a focus on the usefulness of evidence as the basis for determining research perspective and questions; (4) an increased focus on interventions developed outside research teams, for example changes in policy or health services delivery; and (5) the identification of six 'core elements' that should guide all phases of complex intervention research: consider context; develop, refine and test programme theory; engage stakeholders; identify key uncertainties; refine the intervention; and economic considerations. We divide the research process into four phases: development, feasibility, evaluation and implementation. For each phase we provide a concise summary of recent developments, key points to address and signposts to further reading. We also present case studies to illustrate the points being made throughout.

Limitations: The framework aims to help research teams prioritise research questions and design and conduct research with an appropriate choice of methods, rather than to provide detailed guidance on the use of specific methods. In many of the areas of innovation that we highlight, such as the use of systems approaches, there are still only a few practical examples. We refer to more specific and detailed guidance where available and note where promising approaches require further development.

Conclusions: This new framework incorporates developments in complex intervention research published since the previous edition was written in 2006. As well as taking account of established practice and recent refinements, we draw attention to new approaches and place greater emphasis on economic considerations in complex intervention research. We have introduced a new emphasis on the importance of context and the value of understanding interventions as 'events in systems' that produce effects through interactions with features of the contexts in which they are implemented. The framework adopts a pluralist approach, encouraging researchers and research funders to adopt diverse research perspectives and to select research questions and methods pragmatically, with the aim of providing evidence that is useful to decision-makers.

Future work: We call for further work to develop relevant methods and provide examples in practice. The use of this framework should be monitored and the move should be made to a more fluid resource in the future, for example a web-based format that can be frequently updated to incorporate new material and links to emerging resources.

Funding: This project was jointly funded by the Medical Research Council (MRC) and the National Institute for Health Research (Department of Health and Social Care 73514).

Keywords: COMPLEX INTERVENTION; COMPLEXITY; CONTEXT; DEVELOPMENT; EVALUATION; FEASIBILITY; IMPLEMENTATION; INTERVENTION REFINEMENT; PROGRAMME THEORY; STAKEHOLDERS; SYSTEMS; UNCERTAINTIES.

Plain language summary

Interventions are actions taken to make a change, for example heart surgery, an exercise programme or a smoking ban in public. Interventions are described as complex if they comprise several stages or parts or if the context in which they are delivered is complex. A framework on how to develop and evaluate complex interventions was last published by the Medical Research Council in 2006 (Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and Evaluating Complex Interventions . London: Medical Research Council; 2006). This document describes how the framework has been updated to include advances in research methods and thinking and presents the new framework document. The updating process had four stages: (1) review of the literature to identify areas requiring update; (2) workshop of experts to discuss topics to update; (3) open consultation on a draft of the framework; and (4) writing the framework. The updated framework divides the research process into four phases: development, feasibility, evaluation and implementation. Key updates include: the definition of a complex intervention was changed to include both the content of the intervention and the context in which it is conductedaddition of systems thinking methods: an approach that considers the broader system an intervention sits withinmore emphasis on interventions that are not developed by researchers (e.g. policy changes and health services delivery)emphasis on the usefulness of evidence as the key goal of complex intervention researchidentification of six elements to be addressed throughout the research process: context; theory refinement and testing; stakeholder involvement; identification of key uncertainties; intervention refinement; and economic considerations. The updated framework is intended to help those involved in funding and designing research to consider a range of approaches, questions and methods and to choose the most appropriate. It also aims to help researchers conduct and report research that is as useful as possible to users of research.

Publication types

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Forecasting

- Referral and Consultation*

Grants and funding

- SPHSU14/CSO_/Chief Scientist Office/United Kingdom

- MC_UU_00022/2/MRC_/Medical Research Council/United Kingdom

- SPHSU18/CSO_/Chief Scientist Office/United Kingdom

- NIHR200174/DH_/Department of Health/United Kingdom

- MC_PC_13027/MRC_/Medical Research Council/United Kingdom

- SPHSU16/CSO_/Chief Scientist Office/United Kingdom

- MC_UU_12017/11/MRC_/Medical Research Council/United Kingdom

- MC_UU_12017/14/MRC_/Medical Research Council/United Kingdom

- MC_UU_00022/1/MRC_/Medical Research Council/United Kingdom

- MC_UU_00022/3/MRC_/Medical Research Council/United Kingdom

- MC_UU_12011/4/MRC_/Medical Research Council/United Kingdom

- IS-BRC-1215-20007/DH_/Department of Health/United Kingdom

- SPHSU17/CSO_/Chief Scientist Office/United Kingdom

- MC_UU_12017/15/MRC_/Medical Research Council/United Kingdom

Internet Explorer is no longer supported by Microsoft. To browse the NIHR site please use a modern, secure browser like Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox, or Microsoft Edge.

NIHR publishes new framework on complex interventions to improve health

Published: 01 October 2021

The NIHR and The Medical Research Council (MRC) has launched a new complex intervention research framework.

The new framework provides an updated definition of complex interventions, highlighting the dynamic relationship between the intervention and its context.

Complex interventions are widely used in the health service, in public health practice, and in areas of social policy that have important health consequences, such as education, transport, and housing.

Interest in complex interventions has increased rapidly in recent years. Given the pace and extent of methodological development, there was a need to update the core guidance and address some of the remaining weaknesses and gaps.

Using the framework’s core elements

There are four main phases of research: intervention development or identification, e.g. from policy or practice, feasibility, evaluation, and implementation.

At each phase, the guidance suggests that six core elements should be considered:

- how does the intervention interact with its context?

- what is the underpinning programme theory?

- how can diverse stakeholder perspectives be included in the research?

- what are the key uncertainties?

- how can the intervention be refined?

- do the effects of the intervention justify its cost?

These core elements can be used to decide whether the research should proceed to the next phase, return to a previous phase, repeat a phase, or stop.

The journey of a research project through the phases of complex intervention research is illustrated in the below NIHR-funded study: Football Fans In Training (FFIT) .

A randomised controlled trial set in professional football clubs established the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the Football Fans in Training (FFIT) programme. FFIT aimed to help men lose at least 5-10% of their weight and keep it off over the long term. The programme was developed to appeal to Scottish football fans and to help them improve their eating and activity habits.

Researchers found that participation in FFIT leads to significant sustained weight loss and improvements in diet and physical activity. As well as losing weight, participants benefited from reduced waist size, less body fat and lower blood pressure, which can all be associated with a lower risk of heart disease, diabetes and stroke. The study team considered all of the 6 core elements of complex intervention research, during each of the four phases of the research.

Implementation was considered from the outset, the study team engaged with key stakeholders in the development phase to explore how the intervention could be implemented in practice, if proven to be effective.

A cost effectiveness analysis demonstrated that FFIT was inexpensive to deliver, making it appeal to decision makers for local and national health provision. The positive and sustainable results have made the programme appealing for nations with similar public health priorities such as the reduction of obesity, heart disease and improvement of mental health.

Professor Hywel Williams, NIHR Scientific and Coordinating Centre Programmes Contracts Advisor, said: “This updated framework is a landmark piece of guidance for researchers working on such interventions. The updated guidance will help researchers to develop testable and reproducible interventions that will ultimately benefit NHS patients. The guidance also represents a terrific collaborative effort between the NIHR and MRC that I would like to see more of.”

Professor Nick Wareham, Professor Nick Wareham, Chair of MRC’s Population Health Sciences Group, said: “Previous versions of the guidance on the development and evaluation of complex interventions have been extremely influential and are widely used in the field. We are delighted that the successful partnership between MRC and NIHR has enabled the guidance to be updated and extended. It is particularly important to see how the new framework brings in thinking about the interplay between an intervention and the context in which it is applied.”

Dr Kathryn Skivington, Research Fellow, MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit and lead author of the framework, said: “The new and exciting developments for complex intervention research are of practical relevance and I feel sure they will stimulate constructive debate, leading to further progress in this area.”

Read the full paper, published in the British Medical Journal

Find out more in the NIHR Journals Library

Latest news

NIHR awards £5m for a HealthTech Research Centre Network to provide national leadership for the development of medical devices, diagnostics and digital technologies

Nurses and midwives awarded £3m from the NIHR Research for Patient benefit programme across 16 projects

Children’s mental health research project wins £1.5m research funding

New funding initiatives for novel brain tumour research as part of £40m investment

NIHR-funded calculator uses NHS data to predict patients’ risk of falling

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 23 January 2018

Using the Medical Research Council framework for development and evaluation of complex interventions in a low resource setting to develop a theory-based treatment support intervention delivered via SMS text message to improve blood pressure control

- Kirsten Bobrow ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2452-2482 1 , 2 , 7 ,

- Andrew Farmer 3 ,

- Nomazizi Cishe 4 ,

- Ntobeko Nwagi 4 ,

- Mosedi Namane 5 ,

- Thomas P. Brennan 6 ,

- David Springer 6 ,

- Lionel Tarassenko 6 &

- Naomi Levitt 1 , 2

BMC Health Services Research volume 18 , Article number: 33 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

15k Accesses

23 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

Several frameworks now exist to guide intervention development but there remains only limited evidence of their application to health interventions based around use of mobile phones or devices, particularly in a low-resource setting. We aimed to describe our experience of using the Medical Research Council (MRC) Framework on complex interventions to develop and evaluate an adherence support intervention for high blood pressure delivered by SMS text message. We further aimed to describe the developed intervention in line with reporting guidelines for a structured and systematic description.

We used a non-sequential and flexible approach guided by the 2008 MRC Framework for the development and evaluation of complex interventions.

We reviewed published literature and established a multi-disciplinary expert group to guide the development process. We selected health psychology theory and behaviour change techniques that have been shown to be important in adherence and persistence with chronic medications. Semi-structured interviews and focus groups with various stakeholders identified ways in which treatment adherence could be supported and also identified key features of well-regarded messages: polite tone, credible information, contextualised, and endorsed by identifiable member of primary care facility staff. Direct and indirect user testing enabled us to refine the intervention including refining use of language and testing of interactive components.

Conclusions

Our experience shows that using a formal intervention development process is feasible in a low-resource multi-lingual setting. The process enabled us to pre-test assumptions about the intervention and the evaluation process, allowing the improvement of both. Describing how a multi-component intervention was developed including standardised descriptions of content aimed to support behaviour change will enable comparison with other similar interventions and support development of new interventions. Even in low-resource settings, funders and policy-makers should provide researchers with time and resources for intervention development work and encourage evaluation of the entire design and testing process.

Trial registration

The trial of the intervention is registered with South African National Clinical Trials Register number (SANCTR DOH-27-1212-386; 28/12/2012); Pan Africa Trial Register (PACTR201411000724141; 14/12/2013); ClinicalTrials.gov ( NCT02019823 ; 24/12/2013).

Peer Review reports

Raised blood pressure is an important and common modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular and related diseases including stroke and chronic kidney disease [ 1 ]. Although evidence exists that lowering blood pressure substantially reduces this risk, strategies to achieve sustained blood pressure control are complex. These include modifying a range of behaviours related to health including attending clinic appointments, taking medication regularly and persisting with treatment [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ].

Mobile communications technology has the potential to support behaviour change and treatment adherence in real time by facilitating remote, interactive, timely access to relevant information, providing context-specific support and prompts to action [ 6 ].

Systematic reviews of health behaviour change interventions delivered by mobile phones or devices (m-health) have shown small beneficial effects for some conditions in some settings but results are not consistent [ 7 , 8 ]. Some though not all trials have shown modest effects on treatment adherence and disease outcomes for m-health interventions among adults living with HIV [ 9 , 10 ]. Similar results have been found in trials of m-health interventions to support behaviour change for people with high blood pressure, diabetes, and heart disease [ 11 , 12 ].

Behavioural interventions, including those delivered using m-health technologies are often not systematically developed, specified, or reported [ 13 ]. The potential to accumulate evidence of effectiveness and to identify the “active components” in successful m-health interventions depends in part on replication of successful interventions across settings and in part on refining interventions (adding or subtracting elements) using evidence of behaviour change [ 14 ]. Adequate descriptions of the theory of the intervention and specific intervention components are needed to extend the evidence base in the field and to facilitate evidence synthesis [ 15 ].

Several frameworks are now available to guide intervention development but there is limited evidence of their application to describe the development of m-health interventions particularly in resource constrained settings [ 16 , 17 ]. The Medical Research Council (MRC) Framework for the development of complex interventions (initially published in 2000 and up-dated in 2008) has been used successfully across disciplines which suggest its flexible, non-linear approach may be usefully applied to the iterative design processes used in the development of new technology-based systems [ 15 , 18 , 19 , 20 ].

The aim of this paper is to describe our experience of using the 2008 MRC framework to develop and test a theory-based behaviour change intervention to support adherence to high blood pressure treatment delivered by mobile phone text message; to reflect on the benefits and challenges of applying this framework in a resource constrained setting, and to describe the final intervention in line with reporting guidelines for a structured and systematic description [ 13 ].

We used a non-sequential, flexible approach guided by the 2008 MRC Framework for the development and evaluation of complex interventions (see Fig. 1 ) [ 18 ]. Table 1 shows the stages of the 2008 MRC framework alongside with the activities we undertook in the development process. Implicit in this development process is the identification of contextual factors that can affect outcomes [ 21 ].

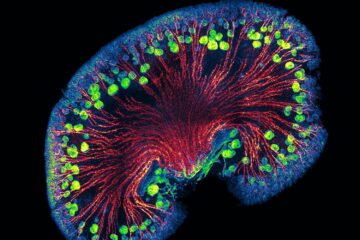

Process of intervention development adapted from Smith et al. [ 20 ]

Developing a complex intervention

Identifying the evidence base.

We searched PubMed, Cochrane reviews, and Google for systematic reviews and published original studies from 2000 onwards that were written in English. We used search terms including “mobile health, text-message, adherence, high blood pressure, hypertension and adherence”. We revisited the literature and narrowed the focus of our reviews as development of the intervention progressed. We set up automatic alerts to monitor the relevant literature for updates.

There is some evidence that clinical outcomes for treatment of chronic conditions can be modestly improved through targeting adherence behaviour [ 4 , 22 ], with a number of trials in hypertension [ 5 , 23 , 24 , 25 ]. The most effective strategies for improving adherence were complex including combinations of more instructions and health education for patients, disease and treatment-specific adherence counselling, automated and in-person telephone follow-up, and reminders (for pills, appointments, and prescription refills) [ 22 ]. In addition some strategies can be costly, for example with case management and pharmacy-based education. These approaches may not be practical in a low-resource setting.

Some studies report that mobile phone messaging interventions may provide benefit in supporting the self-management of long-term illnesses [ 7 , 26 ], and have the potential to support lifestyle change, including smoking cessation [ 7 , 27 ]. However randomised trials of the effectiveness of mobile phone messaging in the management of hypertension are few, include additional components (telemonitoring), often focus on high-risk groups such as stroke survivors and renal transplant recipients, and are based in high-resource settings [ 23 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 ].

Identifying appropriate theory

We set up an expert multi-disciplinary group comprising two specialist general practitioners, two specialist physicians, three biomedical engineers, a health systems researcher, and an epidemiologist. As a team we met formally to agree upon the research problem and the underlying principles guiding the intervention development process. Thereafter we worked in smaller groups to develop the intervention. We maintained written logs of the iterative steps of the intervention development and remained in regular contact with the full group via email and teleconference. When the group met formally we reported on technical progress, resource allocation, implementation issues, and new evidence from the literature or the field.

We used semi-structured interviews and focus groups with three stakeholder groups: (1) Patients with high blood pressure and other chronic diseases ( n = 35), (2) primary care health professionals (general practitioners, professional nurses, staff nurses, pharmacists, allied health professionals, reception staff) ( n = 12), (3) health care system service providers and subcontractors (provincial health systems managers ( n = 5), third party providers of off-site pre-packaged repeat prescription services ( n = 3)).

South Africa is a middle-income country with high levels of income inequality and a quadruple burden of disease (HIV/AIDS, maternal and child, non-communicable diseases, violence.) [ 32 , 33 ] Health care is provided for most South Africans (over 80%) by publicly funded state run facilities the foundation of which are primary care facilities. Medical doctors and nurses (some who have the right to prescribe medications) staff facilities and provide diagnostic, and monitoring services; treatment including all medications is free for patients attending primary care (user fees for primary care were abolished in 1997.) [ 34 ] National guidelines for the treatment of high blood pressure exist and are regularly updated [ 35 ].There is an essential drugs list and medicines for high blood pressure available in primary care include thiazide and other diuretics, calcium channel blockers, ace-inhibitors, and beta-blockers. Patients maybe prescribed other anti-hypertensive agents like ARBs by specialists. Statins and Aspirin are also available [ 36 ].

With the stakeholders described above we explored the problem of high blood pressure and poor control in busy and resource constrained publically-funded primary care facilities. A range of problems were identified that were seen as barriers to providing optimal care and potential targets for intervention. These included organisation of care (failure of systems for referral between primary and secondary care and medication access), service provision (failure of clinicians to adhere to management guidelines), and patient-level factors such as sub-optimal self-management and treatment adherence. From discussion with the various stakeholder groups it emerged that patient-level factors resulting in failure to attend clinic appointments and collect and take medication regularly was both a major concern and a feasible and acceptable potential target for developing an intervention to improve blood pressure control. The underlying hypothesis was that facilitating communication between patients and the health care system might lead to changes in treatment adherence behaviour and improve health outcomes.

Use of mobile devices for intervention delivery

We framed the use of mobile phones as contextual tools that could deliver support messages when and where needed i.e. at times and places outside of a health care visit (ecological momentary intervention) [ 6 ]. We focused on using widely available existing communication protocols (for example short message service or SMS text messages) that are back-compatible (even the most basic device can send and receive text messages), and adapting participants’ existing technical skills to health specific behaviours rather than focusing on acquisition of new technical skills (for example by giving participants smart phones and asking them to use an app-based intervention).

Behaviour change theory

We explored a range of social cognition models and selected the I-CHANGE model that integrated multiple different elements (awareness, motivation, and action) which have been shown to be important in adherence and persistence with chronic medications [ 22 , 37 ].

Behaviour change techniques

We used behaviour change theory to identify areas of belief or behaviour that might contribute to problems in collecting or taking medication. We then developed and refined the message content and mapped the messages to a common taxonomy of evidence-based behaviour change techniques [ 38 ].

Modelling (phase I)

We tested assumptions about the clarity, perceived usefulness and importance of individual text messages with stakeholder groups. To decide on the most appropriate tone and style of content delivery we tested individual SMS text messages using three different communication styles (directive, narrative vignette, or request). Stakeholders were asked when and how frequently adherence support messages should be sent. Messages that were unclear or ambiguous were modified; messages that were perceived by both patients and providers as not being useful or important were discarded. Patients’ thoughts and comments were also used to generate new content for new messages which were then again mapped to the taxonomy of behaviour change techniques and added to the message library. In addition, we engaged with the two local Community Advisory Boards (made up of community members and clinic patients who act as elected liaisons between the health facility and the community) who provided additional guidance and feedback on the intervention components and other study materials.

Using evidence from the literature alongside the findings from the semi-structured interviews of clinic and pharmacy staff at four representative primary care facilities in Cape Town the group agreed that in order to change adherence-related behaviours the intervention would need to,

Remind patients about up-coming scheduled clinic appointments

Provide relevant health-related information

Help participants plan and organise various treatment adherence behaviours including medication collection and taking, diet, and exercise

Support positive adherence-related behaviours

Help navigate the health care system (e.g. what to do if the patient ran out of medications)

Table 2 gives examples of the SMS texts that were developed, mapped to the taxonomy of behaviour change techniques (along with definitions and message timing) [ 38 ].

Patients and providers reported their thought that all people with high blood pressure could benefit from an intervention. Stakeholder groups reported disliking the idea of trying to target the intervention to particular patient groups, for example those with poor blood pressure control or those who only attend the clinic infrequently. Providers and health system managers cited concerns over the logistics of identifying such groups while patients reported concerns over perceptions of favouritism unrelated to illness severity. Patient groups expressed the opinion that “everyone with high blood pressure” should be offered the intervention and that people who didn’t want the intervention should be allowed to opt out.

Health care providers, particularly front-line staff preferred individual texts presented in a directive-style, for example, “You must take your medicine even if you feel well”. Reasons for this included the need to convey to patients the importance of the information being presented. In contrast all of the patient groups strongly preferred messages that were styled as polite requests, for example, “Please keep taking all your medicine even if you feel well”. Both groups were ambivalent about the use of narrative vignettes (for example “Busi in Langa: I bring my empties to clinic, then they can see I eat my pills right”.) Contextual aspects of the messages were also important (information specific to the clinic) as was the perceived authority of the message – messages signed off by a named provider were valued more highly by participants who felt they would be more likely to respond to such a message. Participants also reported that this was more important than using their name at the start of a message. Providers reported that it would be acceptable for senior staff at the facility to be named (i.e. sign off) in an SMS text as long as the messages were in line with Department of Health guidelines.

Individual SMS text messages are typically limited to 160 characters including spaces. We found that using short simple words was more acceptable to stakeholders than “textese” (a form of text-based slang using non-standard spelling and grammar). We minimised the use of contractions, using only “pls” for “please” and “thnks” for “thank you” and an abbreviation for the clinic name. All stakeholders groups reported on the value of having messages available in a variety of local languages though they did acknowledge that most people text in English (in part because of ambiguities in meaning that can arise from informal word shortening).

Participants reported that they valued the idea of being able to choose the time at which a message was sent so that it would not interfere with other commitments e.g. work or religious-activities. All stakeholders reported valuing the idea of a follow-up text message in the event a participant missed a scheduled appointment. On the basis of these discussions we decided to send follow-up messages to all participants thanking those who had attended on time and encouraging those who had not attended to please rebook their appointment. However, concerns were raised by providers and participants about the appropriate length of time between reminder messages and appointment dates so that people could make changes to their schedule or get in touch with the clinic to change their appointment. As a result, the messages were sent 48 h before and after a scheduled appointment.

Concerns about the potential costs of the intervention to the user were raised by all stakeholder groups. Specific concerns were raised about how to deliver an interactive intervention at little or no cost to the end-user. Solutions which have been used in other settings such as providing small amounts of credit to end-users to engage with an interactive system were rejected by health systems managers and sub-contractors due to concerns that the intervention would be too costly to deliver sustainably at scale. As a result of the telecommunications market in South Africa at the time it was not possible to use free-to-user short codes for interactive SMS text messagss.

Final interventions

The final interventions consisted of an adherence support intervention delivered by a weekly information-only (unidirectional) or interactive (bidirectional) SMS text message delivered at a time and in a language of the user’s choice. Messages were endorsed (signed off by a named provider) and contained content that was credible to both providers and patients and addressed a broad range of barriers to treatment adherence common in the local context. Reminder prompt text messages were sent 48 h before a scheduled clinic appointment (for a follow-up visit or to collect medication) with a follow-up message 48 h later either to thank participants for attending their appointment or to encourage them to rebook in the event of a missed appointment. To enable the system to be interactive we developed a system using free-to-user “Please Call Me” (or Call Me Back Code which is a service available on all local networks which allows a user to prompt someone else to call them) or missed-calls that enabled users to generate automated responses that allowed them to cancel or change their appointment, and change the time and language of the SMS text-messages.

By designing an intervention that was perceived in user-testing to be sent suitably frequently to keep users engaged (but not annoy them), contained content that was useful and could be trusted, and was phrased using polite and respectful language we felt the intervention would increase awareness and support motivation and actions to improve adherence to treatment for high blood pressure.

Modelling process and outcomes

We used a causal model to link theoretically relevant behavioural determinants to specific adherence related behaviours. We linked these to health impacts and outcomes along a hypothesised casual pathway [ 7 , 8 ]. We used validated measures to assess important variables along the causal pathway. (See Fig. 2 ).

Hypothesised causal pathways and measures for evaluation for SMS text Adherence suppoRt (StAR) trial

Assessing feasibility and piloting methods

Availability and use of mobile phones among adults with chronic diseases attending primary care services in south africa.

To test assumptions about access to and use of mobile phones we conducted a cross-sectional survey among adult patients attending any one of five community health centres in the Western Cape Metro Health Districts for treatment of hypertension and other chronic diseases. These outpatient facilities provide comprehensive primary care services for people living in the surrounding areas.

At primary health care level, the service is based on prevention by educating people about the benefits of a healthy lifestyle. Every clinic has a staff member who has the skills to diagnose and manage chronic conditions, from young to elderly patients. Patients can see the same nurse for repeat visits if they come regularly on the hypertension, diabetes or asthma clinic day. Counselling, compliance, and health education are also part of usual care. The service is led by clinical nurse practitioners and supported by doctors.

Arrangements are made by the clinic to minimise patient travel (especially by the elderly) by prescribing supplies of drugs that last one to 3 months. Staff often facilitate the initiation of clubs and special support groups for people with chronic diseases. In this way, a patient can get more information on special care and health education pertaining to their condition.

These primary-level services are supported and strengthened by other levels of care, including acute and specialised referral hospitals. If complications arise, patients will be referred to the next level of care [ 39 , 40 ].

The interviewer-administered questionnaire asked about socio-demographic factors, contact with the clinic, chronic diseases and treatment burdens and about access to and the use of mobile phones. We sampled consecutive consenting adults from outpatient services over a period of 6 weeks. A total of 127 willing and eligible adult patients completed the survey (see Table 3 ). Mean age (SD) was 53.3 (14) years, 73% were women, and two-thirds had at least some high-school education. Ninety percent of participants reported having regular (daily) access to a mobile phone and 80% reported that their phone was with them most or all of the time. Most participants did not share their phones (76%); women reported sharing more frequently than men (24% versus 13%). Most participants (76%) reported having registered their phone numbers in their name and that they had had the same mobile phone number for two or more years (63%).

70% of participants reported feeling very confident about using their phone to receive an SMS text messages, while fewer participants (55%) were as confident about sending SMS text messages. Most (70%) felt very confident about sending a “Please Call Me” a free service provided by South African telecommunications providers across all local networks. Fewer than 10% of participants reported knowing how to use unstructured supplementary service data (USSD) communication protocol services like mobile-phone banking.

When asked about preferred ways for the clinic to be in touch, more women (74%) than men (47%) preferred SMS text messages to phone calls or other methods like home visits. The majority of participants reported that they would find reminders to attend up-coming clinic appoints (92%), collect medications (94%), and take medications (87%) helpful.

Testing procedures

To optimise the intervention and test the technical systems responsible for message delivery we service tested the full intervention package with 19 patients recruited from patient-stakeholder focus groups. We tested the messages in the three languages most commonly used in Cape Town (English, Afrikaans, isiXhosa). Participants were contacted on a weekly basis by a researcher (experienced in qualitative methods) for a semi-structured interview on their experience of the intervention and the SMS text message delivery system. Suggestions were discussed with the intervention development team and changes were made where necessary.

Estimating recruitment and retention

In consultation with the local department of health we identified primary care health centres with high patient loads which might be suitable for a clinical trial to test the intervention. We visited each site to confirm the numbers of patients with high blood pressure using clinic registers, to map out patient flow through the clinic so we could operationalise trial procedures and identify potential challenges and barriers to implementation. One of the requirements for approval from the local department of health for research in public facilities is that normal activities are not interrupted. We therefore selected a health centre with a high caseload of patients with “chronic diseases of lifestyle” where we could recruit, screen, and enrol trial participants without interrupting the usual flow of patients through the clinic services.

We estimated we would be able to screen and recruit between 45 and 120 participants per week based on the functioning of the clinic and the experience of other local researchers [ 41 ]. We tested our capacity to recruit and screen participants using a clinical service offering blood pressure measurement to all patients attending the clinical service prior to the start of the trial. We tested trial registration and enrolment procedures including the receipt of an initial SMS text message at the time of enrolment. We collected detailed contact information on participants as well as the details of two next of kin (or similar) to maximise our chances of remaining in contact with participants for the duration of the trial. We monitored recruitment and retention on an ongoing basis.

Determining sample size

Adequately powered trials of the effects of m-health interventions on important clinical outcomes are required to develop the evidence base for these approaches [ 7 , 8 ]. As blood pressure is strongly and directly related to mortality we selected change in mean systolic blood pressure at 12-months from baseline as our primary outcome (clinical). We selected medication adherence (behavioural) as a secondary outcome. We decided not to report these as co-primary outcomes. As there were no previous trials of the effect of adherence support delivered by SMS text on blood pressure measures we used data from published trials of behavioural interventions delivered using other methods to estimate sample size [ 42 ]. A decrease in systolic blood pressure of 5 mmHg is associated with clinically important reduction in the relative risk of stroke and coronary heart disease events [ 43 ]. Based on a study population similar to that expected for the trial population we used the standard deviation (SD) of systolic blood pressure (22.0 mmHg) to calculate the required sample size [ 44 ]. We proposed an intended target sample size of 1215 participants, allowing for 20% loss to follow-up, (at least 405 in each group) to detect an absolute mean difference in SBP of 5 mmHg (SD 22) at 12 months from baseline, with 90% power and 0.05 (two-sided) level of significance. We used an intention to treat (ITT) approach for all analyses.

Evaluating a complex intervention

Assessing effectiveness.

We decided that the most appropriate design to evaluate the effectiveness of adherence support via SMS text message would be a large single blind (concealed outcome assessment), individually randomised controlled trial. As the effect on clinical outcomes of an informational versus interactive system of SMS text messages was unclear from the published literature we decided to include two interventions; information-only SMS texts, and interactive SMS texts [ 8 , 45 ]. To try to assess the effects of the behavioural intervention beyond receipt of an SMS text message from the clinic, we decided the control group would receive simple, infrequent text messages (less than one per month) related to the importance of ongoing trial participation [ 46 ]. Details of the intervention can be found in the TIDieR checklist (Table 4 ).

The trial is registered with the South African National Clinical Trials Register number (SANCTR DOH-27-1212-386; 28/12/2012); Pan Africa Trial Register (PACTR201411000724141; 14/12/2013); ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02019823; 24/12/2013).

Understanding change processes

Implementation. fidelity assessment.

SMS text messages were sent using an automated system independent of trial and clinical staff. Participants were informed that not everyone would be receiving the exact same messages. Participants were also asked not to share the SMS text messages with others. Intervention fidelity was ensured by confirming the receipt at least of an initial “Welcome” SMS text message for all enrolled trial participants prior to randomisation. Message delivery reports were monitored throughout the trial to check the intervention was being delivered as planned. In addition, we also set up a system of sentinel-phones (using the five most common entry-level handsets in South Africa) registered and allocated to receive messages in the same way as trial participants.

The trial interventions were delivered separately from the health care workers providing usual clinical care for participants. For each anticipated study visit (enrolment, 6-month follow-up, 12-month follow-up) standardised protocols were used. Structured logs were used to record detailed information for any interactions between trial staff and participants outside of expected study visits.

Contextual factors

In the final stages of the trial we conducted an independent process evaluation to explore the implementation of the intervention, contextual factors, and potential mechanisms of action. We employed a qualitative design using focus groups and in-depth interviews. The findings from the evaluation have been reported separately [ 47 ].

Cost-effectiveness analyses

We collected information on the costs of developing and delivering the intervention. The findings from this analysis will be reported separately.

Implementation and beyond

Dissemination.

The potential to accumulate evidence of effectiveness and to identify the “active components” in successful m-health interventions depends in part on replication of successful interventions across settings and refining interventions (adding or subtracting elements) using evidence of behaviour change. To facilitate use and adaptation of our intervention we have used recommendations for reporting intervention development to ensure we have described the intervention and its delivery in sufficient detail [ 13 ]. We have registered the trial and published the trial protocol [ 48 ], and we will publish the trial results (using CONSORT reporting guidelines) in an open access journal. We have also published the findings from the process evaluation [in press]. We have reported findings to participants, health care workers, policy makers, and funders.

Surveillance, monitoring, and long-term follow up

We obtained permission to collect routine health data (dispensing and adherence data) from trial participants for a period of 6 months after the trial ended to explore for persistence of effects of the intervention (if any).

Main findings

Using the MRC Framework was feasible in a low-resource multi-lingual setting. The adoption of the framework enabled us to develop a theory- and evidence-based intervention; to specify a proposed causal pathway to modify adherence behaviour and clinical outcomes; to test and refine the intervention delivery system; to design a randomised evaluation of the intervention; and to test and evaluate proposed study procedures.

What is already known on this topic

Mobile devices are a promising approach for delivering health interventions [ 7 , 8 ]. Replication of study findings is hampered by the lack of adequate description of specific intervention components and their theoretical basis [ 13 , 14 , 15 ]. A number of frameworks have been proposed in the health and technology fields to aid the design of technology-based interventions [ 16 , 49 , 50 , 51 ]. The 2008 MRC Framework has been used to design and evaluate interventions across disciplines which suggest its flexible, comprehensive, non-linear, iterative approach may be applicable to the design and evaluation of m-health interventions [ 15 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ].

What this study adds

This paper shows how the framework can be operationalised for an m-health intervention by explicitly mapping the activities, development, and testing to the stages of the 2008 MRC framework. We have also included detailed descriptions of the various aspects of the intervention and its delivery, reported in-line with TIDieR guidelines, which will enable comparison with other m-health interventions and support development of new interventions. Lastly, we have demonstrated that it is feasible and beneficial to use this approach in a multi-lingual low-resource setting.

Limitations of this study/framework

Sufficient time and resources need to be available to apply the Framework and benefit from the iterative development process and from testing of study-related procedures. For example, it took us several months longer than anticipated to complete the intervention development and testing in part because in resource constrained settings like the public health facilities in South Africa it can be challenging for frontline service staff to find time to engage in intervention design activities (interviews, discussions, message library review.)

Whilst the intervention development work was carried out at several sites the clinical trial was at a single-site. In future, we will engage in both development and testing across sites to tease out factors that are common and unique for specific mHealth interventions.

Lastly, attention also needs to be given to field testing of recruitment and retention strategies as there are many instances where trials of mHealth interventions in similar settings are inconclusive because of poor recruitment and high rates of loss to follow-up [ 52 , 53 ].

The MRC Framework can be successfully applied to develop and evaluate m-health interventions in a multi-lingual resource-constrained setting. Detailed descriptions of the development process, the intervention and its delivery may advance the evidence-base for m-health interventions, enabling comparison, adaption, and development of interventions.

Abbreviations

Medical Research Council

SMS text Adherence suppoRt trial

Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2224–60.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R, Prospective Studies Collaboration. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360(9349):1903–13.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Burnier M. Medication adherence and persistence as the cornerstone of effective antihypertensive therapy. Am J Hypertens. 2006;19(11):1190–6.

Viswanathan M, Golin CE, Jones CD, Ashok M, Blalock SJ, Wines RCM, et al. Interventions to improve adherence to self-administered medications for chronic diseases in the United States: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(11):785–95.

Gwadry-Sridhar FH, Manias E, Lal L, Salas M, Hughes DA, Ratzki-Leewing A, et al. Impact of interventions on medication adherence and blood pressure control in patients with essential hypertension: a systematic review by the ISPOR medication adherence and persistence special interest group. Value Health. 2013;16(5):863–71.

Heron KE, Smyth JM. Ecological momentary interventions: incorporating mobile technology into psychosocial and health behaviour treatments. Br J Health Psychol. 2010;15(Pt 1):1–39.

Free C, Phillips G, Galli L, Watson L, Felix L, Edwards P, et al. The effectiveness of mobile-health technology-based health behaviour change or disease management interventions for health care consumers: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2013;10(1):e1001362.

Beratarrechea A, Lee AG, Willner JM, Jahangir E, Ciapponi A, Rubinstein A. The impact of mobile health interventions on chronic disease outcomes in developing countries: a systematic review. Telemed J E Health. 2014;20(1):75–82.

Lester RT, Ritvo P, Mills EJ, Kariri A, Karanja S, Chung MH, et al. Effects of a mobile phone short message service on antiretroviral treatment adherence in Kenya (WelTel Kenya1): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9755):1838–45.

Mbuagbaw L, Thabane L, Ongolo-Zogo P, Lester RT, Mills EJ, Smieja M, et al. The Cameroon Mobile Phone SMS (CAMPS) Trial: A Randomized Trial of Text Messaging versus Usual Care for Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(12):e46909. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0046909

Yasmin F, Banu B, Zakir SM, Sauerborn R, Ali L, Souares A. Positive influence of short message service and voice call interventions on adherence and health outcomes in case of chronic disease care: a systematic review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016;16(1):46.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Adler AJ, Martin N, Mariani J, Tajer CD, Owolabi OO, Free C, et al. Mobile phone text messaging to improve medication adherence in secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. In: The Cochrane Collaboration, editor. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. Chichester: Wiley; 2017. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD011851.pub2 . Cited 19 Jun 2017.

Google Scholar

Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348:g1687.

Michie S, Brown J, Geraghty AWA, Miller S, Yardley L, Gardner B, et al. Development of StopAdvisor. Transl Behav Med. 2012;2(3):263–75.

Lakshman R, Griffin S, Hardeman W, Schiff A, Kinmonth AL, Ong KK. Using the Medical Research Council framework for the development and evaluation of complex interventions in a theory-based infant feeding intervention to prevent childhood obesity: the baby milk intervention and trial. J Obes. 2014;2014:646504.

Nhavoto JA, Grönlund Å, Chaquilla WP. SMSaúde: design, development, and implementation of a remote/mobile patient management system to improve retention in care for HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis patients. JMIR MHealth UHealth. 2015;3(1):e26.

Modi D, Gopalan R, Shah S, Venkatraman S, Desai G, Desai S, et al. Development and formative evaluation of an innovative mHealth intervention for improving coverage of community-based maternal, newborn and child health services in rural areas of India. Glob Health Action. 2015;8:26769.

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1655. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a1655 .

Paul G, Smith SM, Whitford D, O’Kelly F, O’Dowd T. Development of a complex intervention to test the effectiveness of peer support in type 2 diabetes. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7(1):136.

Smith SM, Murchie P, Devereux G, Johnston M, Lee AJ, Macleod U, et al. Developing a complex intervention to reduce time to presentation with symptoms of lung cancer. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62(602):e605–15.

Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, Bond L, Bonell C, Hardeman W, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2015;350:h1258.

Nieuwlaat R, Wilczynski N, Navarro T, Hobson N, Jeffery R, Keepanasseril A, et al. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;11:CD000011.

Márquez Contreras E, de la Figuera von Wichmann M, Gil Guillén V, Ylla-Catalá A, Figueras M, Balaña M, et al. Effectiveness of an intervention to provide information to patients with hypertension as short text messages and reminders sent to their mobile phone (HTA-Alert). Atencion Primaria. 2004;34(8):399–405.

Márquez Contreras E, Vegazo García O, Martel Claros N, Gil Guillén V, de la Figuera v, Wichmann M, Casado Martínez JJ, et al. Efficacy of telephone and mail intervention in patient compliance with antihypertensive drugs in hypertension. ETECUM-HTA study. Blood Press. 2005;14(3):151–8.

Morikawa N, Yamasue K, Tochikubo O, Mizushima S. Effect of salt reduction intervention program using an electronic salt sensor and cellular phone on blood pressure among hypertensive workers. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2011;33(4):216–22.

de Jongh T, Gurol-Urganci I, Vodopivec-Jamsek V, Car J, Atun R. Mobile phone messaging for facilitating self-management of long-term illnesses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD007459.

PubMed Google Scholar

Buhi ER, Trudnak TE, Martinasek MP, Oberne AB, Fuhrmann HJ, McDermott RJ. Mobile phone-based behavioural interventions for health: a systematic review. Health Educ J. 2012; https://doi.org/10.1177/0017896912452071 .

Carrasco MP, Salvador CH, Sagredo PG, Márquez-Montes J, González de Mingo MA, Fragua JA, et al. Impact of patient-general practitioner short-messages-based interaction on the control of hypertension in a follow-up service for low-to-medium risk hypertensive patients: a randomized controlled trial. IEEE Trans Inf Technol Biomed. 2008;12(6):780–91.

Blasco A, Carmona M, Fernández-Lozano I, Salvador CH, Pascual M, Sagredo PG, et al. Evaluation of a telemedicine service for the secondary prevention of coronary artery disease. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2012;32(1):25–31.

Logan AG, Irvine MJ, McIsaac WJ, Tisler A, Rossos PG, Easty A, et al. Effect of home blood pressure telemonitoring with self-care support on uncontrolled systolic hypertension in diabetics. Hypertension. 2012;60(1):51–7.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

McKinstry B, Hanley J, Wild S, Pagliari C, Paterson M, Lewis S, et al. Telemonitoring based service redesign for the management of uncontrolled hypertension: multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2013;346:f3030.

Mayosi BM, Lawn JE, van Niekerk A, Bradshaw D, Abdool Karim SS, Coovadia HM. Health in South Africa: changes and challenges since 2009. Lancet. 2012;380(9858):2029–43.

Ataguba JE-O, Day C, McIntyre D. Explaining the role of the social determinants of health on health inequality in South Africa. Glob Health Action. 2015;8:28665. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v8.28865 .

Wilkinson D, Gouws E, Sach M, Karim SS. Effect of removing user fees on attendance for curative and preventive primary health care services in rural South Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79(7):665–71.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Seedat Y, Rayner B, Veriava Y. South African hypertension practice guideline 2014. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2014;25(6):288–94.

Essential Drugs Programme (EDP) [Internet]. [cited 2017 Jun 21]. Available from: http://www.health.gov.za/index.php/essential-drugs-programme-edp

de Josselin de Jong S, Candel M, Segaar D, Cremers H-P, de Vries H. Efficacy of a web-based computer-tailored smoking prevention intervention for Dutch adolescents: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(3):e82. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2469 .

Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46(1):81–95.

Healthcare 2030: A Future Health Service for the Western Cape [Internet]. Western Cape Government. [cited 2017 Jun 21]. Available from: https://www.westerncape.gov.za/news/healthcare-2030-future-health-service-western-cape

Chronic Care [Internet]. Western Cape Government. [cited 2017 Jun 21]. Available from: https://www.westerncape.gov.za/service/chronic-care

Stewart S, Carrington MJ, Pretorius S, Ogah OS, Blauwet L, Antras-Ferry J, et al. Elevated risk factors but low burden of heart disease in urban African primary care patients: a fundamental role for primary prevention. Int J Cardiol. 2012;158(2):205–10.

Schroeder K, Fahey T, Ebrahim S. Interventions for improving adherence to treatment in patients with high blood pressure in ambulatory settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD004804/abstract .

Collins R, Peto R, MacMahon S, Hebert P, Fiebach NH, Eberlein KA, et al. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Part 2, short-term reductions in blood pressure: overview of randomised drug trials in their epidemiological context. Lancet. 1990;335(8693):827–38.

Tibazarwa K, Ntyintyane L, Sliwa K, Gerntholtz T, Carrington M, Wilkinson D, et al. A time bomb of cardiovascular risk factors in South Africa: results from the heart of Soweto study ‘heart awareness days’. Int J Cardiol. 2009;132(2):233–9.

Finitsis DJ, Pellowski JA, Johnson BT. Text message intervention designs to promote adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART): a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e88166.

Free C, Knight R, Robertson S, Whittaker R, Edwards P, Zhou W, et al. Smoking cessation support delivered via mobile phone text messaging (txt2stop): a single-blind, randomised trial. Lancet. 2011;378(9785):49–55.

Leon N, Surender R, Bobrow K, Muller J, Farmer A. Improving treatment adherence for blood pressure lowering via mobile phone SMS-messages in South Africa: a qualitative evaluation of the SMS-text Adherence SuppoRt (StAR) trial. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16(1):80.

Bobrow K, Brennan T, Springer D, Levitt NS, Rayner B, Namane M, et al. Efficacy of a text messaging (SMS) based intervention for adults with hypertension: protocol for the StAR (SMS Text-message Adherence suppoRt trial) randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):28.

Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1322–7.

Spoth R, Rohrbach LA, Greenberg M, Leaf P, Brown CH, Fagan A, et al. Addressing Core challenges for the next generation of type 2 translation research and systems: the translation science to population impact (TSci impact) framework. Prev Sci. 2013;14(4):319–51.

Crosby R, Noar SM. What is a planning model? An introduction to PRECEDE-PROCEED. J Public Health Dent. 2011;71(Suppl 1):S7–15.

Rubinstein A, Miranda JJ, Beratarrechea A, Diez-Canseco F, Kanter R, Gutierrez L, et al. Effectiveness of an mHealth intervention to improve the cardiometabolic profile of people with prehypertension in low-resource urban settings in Latin America: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;4(1):52–63.

Lau YK, Cassidy T, Hacking D, Brittain K, Haricharan HJ, Heap M. Antenatal health promotion via short message service at a midwife obstetrics unit in South Africa: a mixed methods study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:284.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the patients; health-care workers; pharmacist; clinic administrative staff for their assistance. We are grateful to the Department of Health of the Western Cape for their support and access to facilities. We are grateful to Professor Krisela Steyn and Professor Brian Rayner for their insight and support. We are also grateful for the administrative support from the Chronic Diseases Initiative for Africa secretariat. We are especially grateful to Sr Carmen Delport and Ms. Liezel Fisher.

This research project is supported by the Wellcome Trust and the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council. AF is a Senior NIHR Investigator, and AF and LT are supported by funding from the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Materials used are publically available Medical Research Council (MRC) Framework on complex interventions. TIDieR check list describing final intervention included in supplementary materials. Additional anonymised data from focus groups and cross-sectional survey available on request.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Chronic Disease Initiative for Africa, Cape Town, South Africa

Kirsten Bobrow & Naomi Levitt

Division of Diabetic Medicine and Endocrinology, Department of Medicine, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa

Primary Care Clinical Trials Unit, Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

Andrew Farmer

Women’s Health Research Unit, School of Public Health & Family Medicine, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa

Nomazizi Cishe & Ntobeko Nwagi

Western Cape Province Department of Health, Cape Town, South Africa

Mosedi Namane

Institute of Biomedical Engineering, Department of Engineering Science, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

Thomas P. Brennan, David Springer & Lionel Tarassenko

Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, Radcliffe Observatory Quarter, University of Oxford, Oxford, OX2 6GG, UK

Kirsten Bobrow

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

KB, AF, TB, NL, BR, MN, LT conceived the study. KB and AF designed and coordinated the study and wrote the protocol. The protocol was refined with contributions from TB, DS, NL, BR, KS, MN, LT, who also contributed to study coordination. NN, NC contributed to the data collection and coding, analysis and edited the manuscript. TB, DS and LT developed and implemented the technical system for sending the SMS text-messages and contributed to the manuscript. LT is the grant holder for the program that supported this work. KB and AF (as joint first authors and equal contributors) wrote the first draft of the manuscript, which was critically revised for important intellectual content by all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. KB and AF are the guarantors of the manuscript, and affirm that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the research being reported; and that no important aspects of the study have been omitted.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kirsten Bobrow .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Cape Town (HREC UCT 418/211, 017/2014), the Oxford Tropical Research Ethics Committee (OXTREC 03–12, 13–14), and the Metro District Health Services, Western Cape (RP 141/2011). Trial conduct was overseen by a trial steering committee. All participants provided written informed consent. All the requirements of the Helsinki Declaration of 2008 were fulfilled.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Bobrow, K., Farmer, A., Cishe, N. et al. Using the Medical Research Council framework for development and evaluation of complex interventions in a low resource setting to develop a theory-based treatment support intervention delivered via SMS text message to improve blood pressure control. BMC Health Serv Res 18 , 33 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2808-9

Download citation

Received : 21 September 2015

Accepted : 15 December 2017

Published : 23 January 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2808-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Intervention development

- MRC framework

- Health care

- Self-management

- Behaviour modification

BMC Health Services Research

ISSN: 1472-6963

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Medical Research Council (MRC)

MRC funds research at the forefront of science to prevent illness, develop therapies and improve human health.

MRC content

- Funding, assessment and award management

- Strategy, remit and programmes

- People, skills and fellowships

- Investments, impacts and engagement

- Institutes, facilities and resources

MRC impact showcase

MRC funded discovery science underpins gene therapy cures

18 April 2024

Potential new treatment strategy for aggressive leukaemia

Trial finds first potential drug for gut damage in malnutrition

15 April 2024

Specific nasal cells protect against COVID-19 in children

View all MRC news

Work in partnership to power more equitable health research

3 April 2024

Extreme pregnancy sickness: the quest for a cause

View all MRC blog posts

Funding opportunities

Mrc centre of research excellence: round two: invited full application.

Apply for MRC CoRE funding to tackle complex and interdisciplinary health challenges.

You must be invited to apply for this stage of the funding opportunity.

Funding for early stage development of new healthcare interventions

Apply to the Developmental Pathway Gap Fund (DPGF) to generate critical preliminary data and de-risk your development strategy for a new medicine, medical device, diagnostic test, or other medical intervention.

You must be based at a research organisation eligible for Medical Research Council (MRC) funding.

View all MRC opportunities

Medical Research Council (MRC) Polaris House, North Star Avenue, Swindon, SN2 1FL

Connect with MRC

Subscribe to ukri emails.

Sign up for news, views, events and funding alerts.

There are no upcoming MRC events at this time.

View all events

This is the website for UKRI: our seven research councils, Research England and Innovate UK. Let us know if you have feedback or would like to help improve our online products and services .

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 04 September 2017

Development of a framework for the co-production and prototyping of public health interventions

- Jemma Hawkins ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1998-9547 1 ,

- Kim Madden 2 ,

- Adam Fletcher 3 ,

- Luke Midgley 1 ,

- Aimee Grant 2 ,

- Gemma Cox 4 ,

- Laurence Moore 5 ,

- Rona Campbell 6 ,

- Simon Murphy 1 ,

- Chris Bonell 7 &

- James White 1 , 2

BMC Public Health volume 17 , Article number: 689 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

19k Accesses

149 Citations

59 Altmetric

Metrics details

Existing guidance for developing public health interventions does not provide information for researchers about how to work with intervention providers to co-produce and prototype the content and delivery of new interventions prior to evaluation. The ASSIST + Frank study aimed to adapt an existing effective peer-led smoking prevention intervention (ASSIST), integrating new content from the UK drug education resource Talk to Frank ( www.talktofrank.com ) to co-produce two new school-based peer-led drug prevention interventions. A three-stage framework was tested to adapt and develop intervention content and delivery methods in collaboration with key stakeholders to facilitate implementation.

The three stages of the framework were: 1) Evidence review and stakeholder consultation; 2) Co-production; 3) Prototyping. During stage 1, six focus groups, 12 consultations, five interviews, and nine observations of intervention delivery were conducted with key stakeholders (e.g. Public Health Wales [PHW] ASSIST delivery team, teachers, school students, health professionals). During stage 2, an intervention development group consisting of members of the research team and the PHW ASSIST delivery team was established to adapt existing, and co-produce new, intervention activities. In stage 3, intervention training and content were iteratively prototyped using process data on fidelity and acceptability to key stakeholders. Stages 2 and 3 took the form of an action-research process involving a series of face-to-face meetings, email exchanges, observations, and training sessions.

Utilising the three-stage framework, we co-produced and tested intervention content and delivery methods for the two interventions over a period of 18 months involving external partners. New and adapted intervention activities, as well as refinements in content, the format of delivery, timing and sequencing of activities, and training manuals resulted from this process. The involvement of intervention delivery staff, participants and teachers shaped the content and format of the interventions, as well as supporting rapid prototyping in context at the final stage.

Conclusions

This three-stage framework extends current guidance on intervention development by providing step-by-step instructions for co-producing and prototyping an intervention’s content and delivery processes prior to piloting and formal evaluation. This framework enhances existing guidance and could be transferred to co-produce and prototype other public health interventions.

Trial registration

ISRCTN14415936 , registered retrospectively on 05 November 2014.

Peer Review reports

There are a range of approaches to public health intervention development [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ]. The UK’s Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance, the most widely cited approach, recommends that intervention development should consist of theory development, identification of an evidence base (typically through a recent or new systematic review), and modelling of processes and outcomes [ 13 ]. Other approaches provide more detailed guidance on: developing intervention or program theory [ 2 , 6 , 9 ]; using mapping techniques to inform the components required in an intervention [ 1 , 5 , 7 , 10 ]; cycles of testing and refinement [ 3 , 8 ] and the use of partnerships with individuals, communities, and service providers [ 4 , 7 , 8 , 12 ]. These guidelines support development of a theoretical rationale for an intervention, but provide scant pragmatic instruction on how to develop intervention materials and delivery methods.

Theory needs to be translated into intervention design in a way that facilitates adoption across settings and maximises implementation. The RE-AIM framework helped to re-focus away from efficacy to effectiveness, and assess the degree of reach, adoption, implementation and maintenance of effects [ 14 ]. As well as identifying reasons for (in)effectiveness, an assumption is that barriers to adoption, implementation and maintenance that are identified in evaluations are addressed in the adaptation of existing or design of new interventions. It is not clear whether this occurs. Even if barriers are addressed, as the policy and practice landscape can change with country, health system and time, some barriers identified may not be relevant in a new system. A method for the rapid identification of potential barriers to effectiveness, possible solutions, testing and re-testing of materials would save the costly implementation of interventions that do not adequately account for variations in context. The involvement of customers in the prototyping of new products has long been used in manufacturing [ 15 ], as a method for gaining feedback and improving design. Intervention design may benefit from incorporating the principles of iterative product development and testing intervention components, or prototyping, with those who deliver and receive interventions [ 16 ].

The concept of Transdisciplinary Action Research (TDAR) [ 12 ] has been developed to support effective collaboration between behavioural researchers, policy makers, frontline public services staff and communities. Building on Lewin’s [ 17 ] concept of ‘action research’ that combines scientific and societal value, TDAR is an approach where researchers from multiple disciplines work with a range of stakeholders and intended beneficiaries to jointly understand social problems and identify practical solutions to them, such as through co-producing new public health interventions [ 5 ]. A key component of this approach to applied social science is the development of sustainable, replicable processes to support effective collaboration between researcher teams, frontline practitioners and communities in order to harness the latent expertise of key stakeholders (for example, those who deliver health promotion to the target population, gatekeepers within settings such as school teachers, managers, owners) so that the acceptability and feasibility of the intervention is addressed and maximised at the development stage [ 5 , 12 , 18 , 19 , 20 ].

We present the framework for co-production and prototyping which was used to guide the adaptation of the ASSIST smoking prevention intervention to develop detailed content and delivery processes for two new peer-led drug prevention interventions, one as an adjunct to the ASSIST intervention (+Frank) and the other a standalone drug prevention intervention (Frank friends).

Case study: ASSIST + Frank intervention development study