How to conduct a literature review

The purpose of literature reviews and how to execute them.

Agencja Fotograficzna Caro / Alamy Stock Photo

In recent decades, the ‘evidence-based medicine’ movement has become widely accepted and, consequently, decisions regarding what is best practice are informed by the best available evidence [1] . However, an ever-increasing quantity of evidence published in literature has meant that healthcare providers, researchers, and policy makers are inundated with unmanageable amounts of information, which can hinder, rather than inform, rational decision making [2] . It is therefore vital that healthcare professionals, including pharmacists, appreciate the importance of evaluating the available evidence when attempting to answer a clinical question [3] . A literature review can therefore be considered “the comprehensive study and interpretation of literature that relates to a particular topic” [4] .

When conducted correctly, a literature review can be viewed as more than simply a cursory overview of the literature on a given topic. Indeed, they are often viewed as a piece of research in their own right. A historical example of the value of literature reviews in informing evidence-based practice is that of streptokinase in the treatment of myocardial infarction (MI). In the 1970s, 33 separate clinical trials comparing streptokinase with a placebo for the treatment of MI had been conducted and their results published. Individually, these trials provided inconclusive evidence regarding the role of streptokinase. However, a re-analysis of their combined results clearly demonstrated the beneficial effect of streptokinase. As a result the medicine became part of the standard treatment following MI, thereby transforming care and saving lives [2] .

Narrative versus systematic literature reviews

Literature reviews can be broadly divided into narrative (descriptive) reviews and systematic reviews [5] . The most important difference between the two categories of reviews is the difference in their level of associated scientific rigour. Narrative literature reviews provide an overview of the literature, typically from the perspective of an ‘expert in the field’ [1] . Such reviews often report findings in a format that includes a brief summary of each included study. While such reviews can be informative, particularly when there has been no previous attempt to assimilate the literature in a given area, narrative reviews are often criticised as having a high risk of various types of bias associated with them [6] . Narrative reviews typically rely on subjective and non-systematic methods of selecting and reviewing data. Consequently, authors may intentionally or unintentionally cite only those literature sources that reinforce the author’s preconceived hypotheses or promote their own views on a topic [7] .

In contrast to a narrative review, a systematic literature review aims to identify all the available evidence on a topic and appraise the quality of that evidence [4] . Therefore, such reviews have the ability to either answer the research question or, failing that, identify gaps in the existing literature which highlight the need for further high quality research into a specific area [8] . Established in 1993, the Cochrane collaboration is an international organisation that produces systematic reviews, often regarded as the gold standard of evidence, concerning the effectiveness of healthcare interventions.

The purpose of a literature review

Literature reviews may be conducted for a variety of reasons, for example, to form part of a research proposal or introductory section in an academic paper, or to inform evidence-based practice [8] . The original focus of evidence-based medicine concerned mainly clinical research questions, such as the streptokinase example. However, increasingly, more research is being conducted in the area of health services research, which incorporates social science perspectives with the contribution of individuals and institutions that deliver care. Pharmacy practice research (a sub-type of health services research) is concerned with investigating how and why people access pharmacy services, new roles for pharmacists, and outcomes for patients as a result of pharmacy services [9] . Whether conducting either a clinical pharmacy or a pharmacy practice literature review, the following basic principles outlined in this article should be followed.

Searching with a strategy

While time and resource constraints may not allow for a definitive systematic review to be conducted, those attempting to undertake a literature review should nevertheless adopt a ‘systematic approach’ [10] . The first step in any literature review is to define the research question (i.e. the scope of the review). This will inform which studies or other forms of evidence are to be included and excluded from the literature review.

Questions that should be asked at this stage include:

- Which study designs are relevant to the review? For example, double-blind randomised controlled trials, observational studies or qualitative research.

- Is there a particular population of interest? For example, paediatrics, pregnant women or people living in care homes.

- Are there particular outcomes of interest? For example, mortality, costs or quality of life.

The literature search strategy is a fundamental component of any literature review, because errors in the search process could produce an incomplete and therefore biased evidence base for the review. Where possible, reviewers should consult with a pharmacy or healthcare librarian who can assist in developing and refining an appropriate search strategy [11] . The search should be conducted in more than one electronic database to help ensure all relevant papers are identified. The main medical literature databases are Medline and Embase. International Pharmaceutical Abstracts (IPA) is also an important database to consider because it indexes many pharmacy-specific journals not found in the larger databases. It should also be remembered that pharmacy literature often overlaps with other disciplines therefore consideration should be given to databases such as the Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL), as well as condition-specific databases, for example PsycInfo.

When conducting searches on electronic databases, thought must be given to the search terms used. Several keywords can exist for each search term and all should be included in the search (e.g. older adult/elderly/aged, are all terms that could be used synonymously). Most databases also have the facility to identify all possible endings of the key terms; this is usually denoted with an asterisk. For example, by searching for ‘pharm*’, articles containing any of the following would be retrieved: pharmacist, pharmacists, pharmacy, pharmaceutical. Boolean operators (e.g. ‘and’, ‘or’, ‘not’) can also be used to combine search terms to refine the search results [12] .

Avoiding publication bias

It has been well documented that studies that report significant results are more likely than those reporting non-significant results to be published, cited by others and produce multiple publications, introducing what is known as ‘publication bias’. Consequently, such studies are also more likely to be identified and included in systematic reviews [13] .

For this reason, efforts should be made to identify all relevant literature on the review topic so the search should not be limited solely to electronic databases [14] . Additional search strategies include hand-checking relevant article reference lists and personal communication with experts in the field. Searching the ‘grey literature’ is of particular importance for pharmacy practice literature reviews because relevant articles written by non-academic pharmacists are often not published in traditional academic journals [15] .

The importance of such additional search strategies cannot be underestimated. Greenhalgh and Peacock reported that, in a literature review concerning innovations in healthcare organisations, 51% of the sources included in the eventual review were identified by hand-searching reference lists, while an additional 24% were identified through personal communications [7] . The search strategy, including databases searched, all search terms used, the limits of the search (for example, written in the English language, published in the last decade), the number of results retrieved from each resource and the date the search was conducted should be carefully documented. Although it can never be guaranteed that the entirety of relevant literature will be identified, conducting the search in a systematic manner will help avoid omissions, and where they do exist they can be said to be unintentional [9] .

Once the search has been performed, the next step is to screen the titles or abstracts (or both) of the identified articles against the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. If the article cannot be excluded on the basis of the information contained in the abstract, efforts must be made to access the full paper in order to reach a decision. Conducting a literature review can be a time-consuming process and the time taken to complete is directly related to number of citations identified by the initial search. Allen et al . [16] calculated that it would take a reviewer more than 1,000 hours to complete a literature review involving the screening of 2,500 articles. For this reason, it is worth considering the use of free citation management software, such as Refworks, Mendeley and Endnote, which can be used to manage references retrieved from the literature search.

Drawing conclusions

Studies identified as part of a literature review may report contradictory findings and the quality of the individual studies will have a direct impact on the overall findings of the literature review. When assimilating the evidence identified, the reviewer should attempt to assess the quality of the evidence provided by the individual studies to arrive at valid conclusions [6] . It is recommended that when conducting a literature review, the author should make a judgement of the quality of the evidence provided within the included studies or articles using appropriate assessment guidelines [17] . For example, the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk-of-bias tool attempts to aid quality assessment in terms of assessing potential sources of bias in studies.

In an effort to draw quantitative conclusions within a systematic review, data from individual studies may be pooled quantitatively and reanalysed. A meta-analysis is a statistical method used to combine the outcomes of individual studies to produce data with more power than the individual studies. By pooling the results of individual studies, the sample size is effectively increased, thereby increasing the statistical power of the analysis, which in turns narrows the confidence interval around the effect size, with the result that the overall estimate of effect is more robust [9] . Individual studies included in the analysis are assigned weights, with greater weight assigned to studies with larger sample sizes. The results of a meta-analysis are often displayed graphically in what is known as a “forest plot” [18] .

Publishing your literature review

Targeting an appropriate journal.

- Ensure the scope of your review aligns with the scope of the journal. Familiarise yourself with the journal’s mission statement and the typical content of the journal.

- Be aware of the journal’s target audience in relation to the scope of the review (e.g. does the journal have a pharmacy-specific or multidisciplinary audience? Does the journal have a national or international readership?)

- Consider whether the journal offers open-access publishing. Increasingly, funding bodies stipulate that articles are published only in open-access journals.

- Look at the journal’s impact factor. While articles published in journals with higher impact factors tend to get cited more, high-impact journals have lower article acceptance rates, making it potentially more challenging to get your review published.

Submitting the manuscript

- Familiarise yourself with the journal’s ‘guidelines for authors’. These will dictate the accepted word limit of a review in addition to other formatting and submission stipulations surrounding tables, figures and references, etc.

- Write a cover letter, addressed to the editor of the journal, to accompany your manuscript submission. The cover letter should highlight why the review is important and why you think it is a good fit for the chosen journal.

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal . You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click:

[1] Akobeng AK. Understanding systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child 2005;90:845–848. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.058230

[2] Mulrow CD. Systematic Reviews: Rationale for systematic reviews. The BMJ 1994;309:597. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6954.597

[3] Guyatt G, Cairns J, Churchill D et al . Evidence-based medicine: a new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. JAMA 1992;268:2420–2425. doi: 10.1001/jama.268.17.2420

[4] Aveyard H. Doing a literature review in health and social care: a practical guide. 3rd Edn. Open University Press 2014. doi: 10.7748/ns.29.27.30.s33

[5] Grant MJ & Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J 2009;26:91–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

[6] Green BN. Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: secrets of the trade. J Chiropr Med 2006;5:101–117. doi: 10.1016/S0899-3467(07)60142-6

[7] Greenhalgh T & Peacock R. Effectiveness and efficiency of search methods in systematic reviews of complex evidence: audit of primary sources. The BMJ . 2005;331:1064–1065. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38636.593461.68

[8] Jesson J & Lacey F. How to do (or not to do) a critical literature review. Pharmacy Education 2006;6:139–148. doi: 10.1080/15602210600616218

[9] Babar Z. Pharmacy Practice Research Methods: Adis/Springer International Publishing, Switzerland, 2015.

[10] McKee M & Britton A. Conducting a literature review on the effectiveness of health care interventions. Health Policy Plan 1997;12:262–267. doi: 10.1093/heapol/12.3.262

[11] McGowan J & Sampson M. Systematic reviews need systematic searchers. J Med Libr Assoc 2005;93:74–80.

[12] Cronin P, Ryan F & Coughlan M. Undertaking a literature review: a step-by-step approach. BJN 2008;17:38–43. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2008.17.1.28 059

[13] Sterne J, Egger M & Smith GD. Investigating and dealing with publication and other biases in meta-analysis. The BMJ 2001;323:101. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7304.101

[14] Crumley ET, Wiebe N, Cramer K et al . Which resources should be used to identify RCT/CCTs for systematic reviews: a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol 2005;5:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-5-24

[15] Charrois T, Durec T & Tsuyuki R. Systematic reviews of pharmacy practice research: methodologic issues in searching, evaluating, interpreting, and disseminating results. Ann Pharmacother 2009;43:118–122. doi: 10.1345/aph.1l302

[16] Allen E & Olkin I. Estimating time to conduct a meta-analysis from number of citations retrieved. JAMA 1999;282:634–635. PMID: 10517715

[17] Jüni P, Altman DG & Egger M. Assessing the quality of controlled clinical trials. The BMJ 2001;323:42–46. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7303.42

[18] Lewis S & Clarke M. Forest plots: trying to see the wood and the trees. The BMJ 2001;322:1479–1480. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7300.1479

You might also be interested in…

Case-based learning: social prescribing and pharmacy professionals

Government introduces ‘emergency ban’ on overseas prescriptions for puberty blockers

Our experience as pharmacists in ‘SPACE’

- University of Michigan Library

- Research Guides

Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Literature Reviews

- Drug Information

- Point of Care Resources

- Finding & Using Data & Statistics

- Patient Safety

- Citation Management (EndNote, Mendeley, Zotero) This link opens in a new window

- Mobile Resources

- Creating a Well-Focused Question

- Searching PubMed

- PubMed - Article Abstract Page

- Searching Other Databases - Embase

- Searching Other Databases - International Pharmaceutical Abstracts

- Academic/Professional Integrity at UM

- Research Data Management This link opens in a new window

- NIH Public Access Policy

- Research Funding & Grants This link opens in a new window

Writing literature reviews - an article from Nature

Tips from 8 authors.

- How to Write a Superb Literature Review

What is a Literature Review?

A literature review surveys scholarly articles, books, dissertations, conference proceedings & other resources that are relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory & provides context for a dissertation by identifying past researchon a topic.

Research tells a story, & the existing literature helps us identify where we are in the story currently. It is up to those working on a research project to continue that story with new research and new perspectives, but they must first be familiar with the story before they can move forward.

Purpose of a Literature Review

A literature review:

- Helps you to discover the research that has been conducted on a topic already & identifies gaps in current knowledge

- Increases the breadth of your knowledge in your area of research

- Helps you identify seminal works in your area

- Allows you to provide the intellectual context for your work & position your research with other, related research

- Provides you with opposing viewpoints

- Helps you to discover research methods that may be applicable to your work

Greenfield, T. (2002). Research methods for postgraduates. 2nd ed. London: Arnold.

While there are many specific types of literature reviews, you will be writing a critical literature review to demonstrate your knowledge of a specific area & that your project is viable.

To read more about the different types of reviews, read this article, which provides a good overview: Maria J. Grant & Andrew Booth. "A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies". Health Information and Libraries Journal (26):91–108. DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

The Process of Writing a Literature Review

Frequently asked questions.

What kinds of literature are appropriate for my research question? This will depend on your area of research, but in the health sciences, you will most often rely on scholarly journal articles, patents, conference proceedings, & data sets.

How much literature should I use? There is no standard answer to this question, but make sure that you have enough literature to tell your story. Discuss this question with your advisor & peers.

How will I find all appropriate information to inform my research? You should consult multiple databases & resources appropriate for your research area so that you can have a comprehensive view of the research that has already been done in your area. Browse the Pharmacy research guide for databases & other recommended resources. Also consult with your informationist at the Taubman Health Sciences Library to determine the resources you should investigate.

How will I evaluate the literature to include trustworthy information and eliminate unnecessary or untrustworthy information? Start with scholarly sources, such as peer-reviewed journal articles & books. Always pay attention to creditability of the source(s) & the author(s) you cite. Citation analysis (see research guides http://guides.lib.umich.edu/citeanalysis & http://guides.lib.umich.edu/citation ) can be useful to check the creditability of sources & authors.

How should I organize my literature? What citation management program is best for me? Citation management software, such as Mendeley, a free citation management program, helps you collect & organize references & easily insert citations & format citations & bibliographies in thousands of styles in your Word document.

To choose the program that's right for you, consider which one works best with your literature search & writing process. This guide compares different types of citation management software & provides tutorials for each type. You may also ask your library informationist for advice.

How do I ensure academic integrity (i.e., avoid plagiarism)? Familiarize yourself with different types of intentional and unintentional plagiarism and learn about the University's standards for academic integrity here. Remember, citation management tools can help you avoid unintentional plagiarism by making it easy to collect & cite sources.

What Kind of Literature Should You Choose?

Different types of information sources may be critical for particular disciplines. Please contact your library informationist for additional guidance on information sources appropriate to your research. In addition to books, reference resources, journal articles, & datasets, these sources may be helpful.

Government documents

The U.S. Government Printing Office produces a great deal of information that is useful to researchers. Congress, the Supreme Court, the Office of the President & federal agencies are rich sources of policy information, legislation, & historical records. The University of Michigan's Clark Library is a federal depository library. Librarians there can help you find documents and records created by the federal government, as well as state & local laws & legislation. International government information can be found in United Nations documents , available in print & online since 1946. Also check the Grey Literature guide for more resources.

Statistics reported by government or private sources can be useful, but can also be difficult to find. Use the Health Statistics research guide for more information on how to search & for sources.

Grey Literature

Theses & Dissertations : Dissertations on topics similar to yours may contain information & technical details not published in other forms. You may also be inspired by how others approach similar topics.

Conference proceedings : For many fields, researchers present their most up-to-date research results at professional conferences. These results will later be published in conference proceedings, abstracts, or preprints.

Other unpublished information : For all of the above and resources, including clinical & pharmaceutical research, FDA reports, & more, visit the Grey Literature research guide .

Related Research Guides

- Grey Literature Resources & strategies for searching for information not contained in databases.

- Finding Tests & Measurement Instruments Resources, tips, & tricks for finding tests & measurement instruments in the health & social sciences.

- Bioinformatics Resources on the interdisciplinary science that uses information technology to solve molecular biology problems.

- Research Impact Assessment (Health Sciences) Explore methods and tools for assessing your research impact, including citation tracking and altmetrics.

Writing Help

- Graduate Students - Sweetland Center for Writing One-on-one assistance & workshops, all free.

- Graduate Student Writing Clinic

Pharmacy research project guidance: Doing your literature review

- Project Management

- Ethical Approval

- Doing a systematic literature search

- Evaluating your sources

- Doing your literature review

- Citing references

- Using EndNote

- File and Data Management

- Your Lab/Log Book

- Reflective Writing

- Supervisory Expectations

- Frequently Asked Questions

Introduction

All projects will include a literature review:

- In a lab-based project the review may just be part of the introduction helping to outline the state of the knowledge and gap you are trying to address.

- For literature-based projects this will be the bulk of your discussion, although the way your report is structured will depend on the type of review you are doing. If you are doing a systematic review you will need to follow a specific protocol for writing it up. See ' Doing a systematic literature search ' for guidance and links.

Getting started

- Video tutorial on doing a literature review

A literature review sets up your project and positions it in relation to the background research. It also provides evidence you can refer back to later to help interpret your own results. When getting started on your literature review, it helps to know what role this plays in your overall project.

A literature review:

- Provides the background / context to your topic

- Demonstrates familiarity with previous research

- Positions your study in relation to the research

- Provides evidence that may help explain your findings later

- Highlights any gaps in the research

- Identifies your research question/s

In your literature review you should include:

- Background to the topic (e.g. general considerations, mechanisms of formation, analytical techniques, etc…)

- Why it is important (e.g. food with improve flavour, less carcinogens, more taste, less processed foods, new probiotics ......... & etc.)

- What research has been performed and what has been found out

- The specific area you are interested in (e.g. cheese, snacks, fruits, ….)

- Current ideas and hypotheses in this area

- The key research questions which remain

It can seem difficult to know where to start with your literature review, but to a certain extent it doesn’t matter where you start…as long as you do!

If you like understanding the bigger picture and seeing the whole of an idea before getting into the detail – try starting with a general text and then using the bibliography of this to find more specific journal articles.

If you like to start small with one idea or study, find a relevant journal article or single study and then build up by trying to find related studies and also contrasting studies.

Further help

For more on this view the video tutorial on the other tab in this box, or take a look at these study guides:

- Starting a literature review

- Undertaking a literature review

If you are unable to view this video on YouTube it is also available on YuJa - view the Doing your literature review video on YuJa (University username and password required)

Read the script for the video (PDF)

Note-taking

- Tips on note-taking

- Video tutorial on critical note taking

A key to a good literature review, is having a good system for recording and keeping track of what you are reading. Good notes means you will have done a lot of the thinking, synthesising, and interpreting of the literature before you come to write it up and it will hopefully make the writing process that bit smoother. Systematic note-taking will also ensure you have all the details you need to write your references and won’t accidentally plagiarise.

Have a format for recording your notes that suits you – whether this is in a table, bullet points, spider diagrams, using a programme like Evernote, or in a traditional notebook!

Tables can be a useful way of recording notes for a literature review as it enables you to compare and contrast studies side-by-side in the table. It also forces you to write a concise summary or it won’t fit into the table!

e.g. A suggested outline for a note-making table

Have a system for distinguishing quotations and your own words – you don’t want to accidentally include something only to discover it was someone else’s words and you may have plagiarised by mistake. Always make sure your quotation marks are clear in your notes (it is easy to miss them in a hurry) and it really helps to record the page number of any direct quotation so you can go back to check easily.

Avoid the temptation to copy out text – copying out large chunks of text is slow and also means you tend not to process and understand what you copy. Summarising and writing short phrases instead means you are likely to have a better understanding and will remember it and be able to use your notes more easily later.

Summarise – writing a short summary or overview of what you have just read helps you to clarify their argument and position. It also means you have a handy short reminder when you come back to it later – you don’t want to be re-reading notes that are as long as the original text in the first place!

Always record the full bibliographical details – it only takes a few moments to write down everything you need for your reference. You may think it is fine to leave it as you will be able to find these details later…but you probably won’t and you will waste time searching for them when your deadline is fast approaching.

A top tip if you find it hard to put things in your own words – try reading a longer section of the text before taking notes. It is very difficult to paraphrase something line-by-line as you go along, because everything seems important and it is too easy to just lift the phrases the author has used. Reading a longer section will give you a better overview and fuller understanding, meaning you can choose what is important and relevant to your own project.

For more on this watch the video tutorial on the other tab in this box, or take a look at these study guides:

- Managing academic reading

- Effective note-taking study guide This guide produced by the Study Advice Team gives tips on note-taking and outlines some different approaches.

If you are unable to view this video on YouTube it is also available on YuJa - view the Critical note taking video on YuJa (University username and password required)

Referencing and avoiding plagiarism

- Managing references

- Video tutorial on avoiding unintentional plagiarism

It is a good idea to keep your references up to date as you write so that you know exactly where each idea comes from (and it will save a tedious job at the end ).

Make sure you reference every idea that comes from another source, which includes things like images, diagrams, and statistics, not just word-for-word quotations.

Use the referencing style detailed in the 'Referencing' page in this guide and stick to it consistently! Don’t switch between styles or formats. It may seem petty, but meticulously formatted referencing shows you have taken care in your work and have a professional academic approach (and it will get you marks!). You could consider using a reference management tool, such as EndNote Online, for storing your references and inserting them into your report (see the 'Referencing' page ) - this will be essential if you are doing a literature-based project or a systematic review.

A top tip is to have a proof-read through for referencing only – print out your literature review as it is easier to spot mistakes on paper than on screen.

Referencing checklist

- Is every idea from another source referenced?

- Does every word-for-word quotation have quote marks and is referenced?

- Are all paraphrases in your own words (not just changing a few words) and referenced?

- Does every in-text reference match a full reference in the bibliography?

- Are all names and titles in the references spelled correctly?

- Have you followed the department’s preferred referencing style consistently?

For more on this watch the video tutorial on the other tab in this box.

For detailed help on citing references see the Referencing page in this guide:

- Referencing guidance for the Pharmacy research project

If you are unable to view this video on YouTube it is also available on YuJa - view the Avoiding Unintentional Plagiarism video on YuJa (University username and password required)

Structuring your review

A literature review compares and contrasts the research that has been done on a topic. It isn’t a chronological account of how the research has developed in the field nor is it a summary of each source in turn like a ‘book review’. Instead a literature review explores the key themes or concepts in the literature and compares what different research has found about each theme.

Use sub-headings to structure your literature review as this helps you group the different studies to compare and contrast them and avoids a straight chronological narrative.

To help find your sub-headings:

- Brainstorm all the different concepts or themes in the research that relate to your topic or title

- Identify the ones that are important to your research question – think of what the reader needs to know about to understand the different aspects of your project

- Place the themes in an order that would make sense to your reader – usually going from broad themes to themes more directly related to your project (see funnel diagram in Getting started)

- Turn these into sub-headings

- Use these sub-headings as an outline plan for your literature review – what will come under each sub-heading

Below is an example structure of a literature review that starts broad and starts to narrow by linking the concepts that are specific to this project:

For more on this see the following study guide:

Writing the literature review

When writing a literature review, you want to be comparing and contrasting the studies to build up a picture of what the research says about your topic.

This means you should be using comparative and evaluative language more than descriptive language:

For more examples of the kinds of comparative and evaluative language used in literature reviews see:

- Academic Phrasebank Use this site for examples of linking phrases and ways to refer to sources.

Be selective

Also you want to be selective in how you refer to the literature . In a literature review, you don’t have to refer to each study in the same depth. Think of the points you want to make and then include just enough detail about the study to provide evidence for this. For example, you don’t have to analyse the strengths and weaknesses of the methodology for each study in depth, you only need to do this if you are making a point which relates to the methodology or a point about the findings which depends on the methods being robust and valid (e.g. the authors claim there are wide-spread applications of their trials, but they have used a very small sample size, which suggests they can’t make such a bold assertion).

For example - the summary below maps out the state of current research and the positions taken by the key researchers. A significant amount of reading and in-depth understanding of the field has gone in to being able to summarise the research in these few sentences.

Sometimes you need to go into greater depth and refer to some sources in more detail in order to interrogate the methods and stand points expressed by these researchers. Even in this more analytical piece of writing, only the relevant points of the study and the theory are mentioned briefly - but you need a confident and thorough understanding to refer to them so concisely.

For example:

See the following study guide for more on this:

- Developing your literature review

Returning to your literature review - link to the discussion

Once you have written your literature review, its job doesn’t end there. The literature review sets up the ideas and concepts that you can draw upon later to help interpret your own findings.

Do your own findings confirm or contradict the previous research? And why might this be?

If your literature review funnels down from broad to narrow, you can think of your discussion like the other half of the hour-glass, broadening out to the wider applications of your project at the end:

So although you may draft your literature review as one of your first steps, you will probably come back to it towards the end of your project to redraft it to help fit in with your discussion. You may need to emphasise some studies that didn’t initially seem that important, but which are now more useful because of what you have found in your own experiments.

This is an example of the thinking that might go on behind interpreting a result and linking it to the previous literature:

- << Previous: Evaluating your sources

- Next: Citing references >>

- Last Updated: Jun 4, 2024 2:51 PM

- URL: https://libguides.reading.ac.uk/pharmacy-research-project-guide

- Open access

- Published: 11 May 2022

Systematic literature review of pharmacists in general practice in supporting the implementation of shared care agreements in primary care

- Naveed Iqbal ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1807-1424 1 ,

- Chi Huynh ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6982-6642 1 &

- Ian Maidment ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4152-9704 1

Systematic Reviews volume 11 , Article number: 88 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

4871 Accesses

4 Citations

8 Altmetric

Metrics details

Rising demand for healthcare continues to impact all sectors of the health service. As a result of the growing ageing population and the burden of chronic disease, healthcare has become more complex, and the need for more efficient management of specialist medication across the healthcare interface is of paramount importance. With the rising number of pharmacists working in primary care in clinical roles, is this a role that pharmacists could support to ensure the successful execution of shared care agreement (SCA) in primary care for these patients?

Aim of the review

Systematic review to identify activities and assess the interventions provided by pharmacists in primary care on SCA provision and how it affects health-related quality of life (HRQoL) for patients.

Primary studies in English which tested the intervention or obtained views of stakeholders related to pharmacist input to shared care agreement within primary care were included. The following electronic databases were systematically searched from the date of inception to November 2021: AMED®, CINAHL®, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), EMBASE®, EMCARE®, Google Scholar, HMIC®, MEDLINE®, PsycINFO®, Scopus and Web of Science®. Grey literature sources were also searched. The search was adapted according to the respective database-specific search tools. It was searched using a combination of Medical Subject Heading terms (MeSH), free-text search terms and Boolean operators.

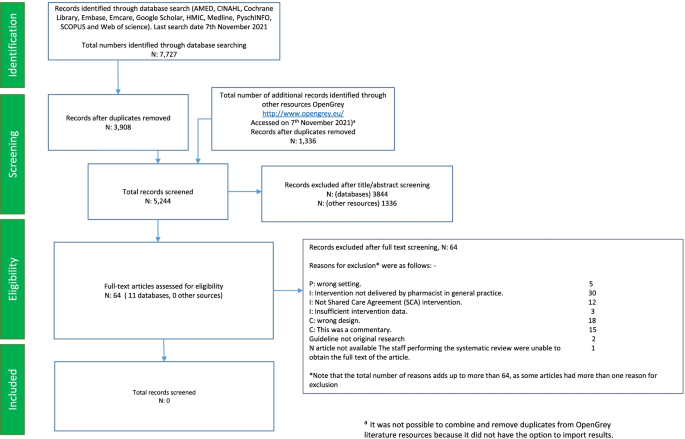

A total of 5244 titles/abstracts were screened after duplicates were removed, and 64 full articles were assessed for eligibility. On examination of full text, no studies met the inclusion criteria for this review.

This review highlights the need for further research to evaluate how pharmacists in general practice can support the safe and effective integration of specialist medication in primary care with the use of SCA.

Systematic review registration

NIHR PROSPERO No: 2020 CRD42020165363 .

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Healthcare systems in the world are facing significant challenges as a result of severe funding pressure, a growing ageing population, societal changes, rising demand and a limited supply of some healthcare professional groups [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. This is compounded by the increasing prevalence of long-term conditions (LTC), in particular, people having two or more conditions which are being supported by different parts of the healthcare system [ 4 ]. The UK is home to the National Health Service (NHS), one of the largest healthcare systems in the world. In the UK, LTCs account for 70% of the NHS healthcare budget [ 4 ]. With the continued demands in the NHS, the current models of dealing with long-term conditions are not sustainable; the need to innovate in order to continue to deliver world-class healthcare outcomes within a limited financial envelope is critical [ 5 ]. Care needs to be provided in the right place and at the right time to ensure that the healthcare system meets the current and future needs of a nation’s healthcare provision [ 6 ]. In response to this new normal, care must not be fragmented between healthcare systems, e.g. pre-hospital, hospital and specialist care [ 7 ].

This is of particular importance in countries where healthcare systems are well developed where care needs to move seamlessly from the gatekeeping primary care systems to the hospital and specialist services for the benefit of patient care [ 8 ]. Effective communication and cooperation between primary and secondary care are critical to making the best use of limited resources [ 9 ] and to ensure the patient receives high-quality joined-up care [ 8 , 10 , 11 ]. A tool that has been used in the literature to support effective integrated care between primary and secondary care is the shared care agreement (SCA) [ 12 , 13 , 14 ]. The SCA was designed to provide a framework for the seamless sharing of care and to facilitate the passage of hospital-prescribed medication or a consultant-managed patient into primary care.

The term shared care agreement has various definitions, none of which is universally agreed on [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ]. The primary description to describe shared care was by Hickman et al. in their seminal paper on the taxonomy of shared care in 1994 [ 15 ]. The original definition of shared care described shared care as The joint participation of general practitioners and hospital consultants in the planned delivery of care for patients with chronic inflammatory musculoskeletal disorders, informed by an enhanced information exchange over and above the routine clinic, discharge and referral letters [ 15 ]. A more recent evolved definition describes these arrangements as the joint participation of primary and speciality care practitioners in the planned delivery of care for patients with a chronic condition, informed by enhanced information exchange, over and above routine discharge and referral notices [ 16 ]. This evolved definition takes into account the changes in primary care since the primary definition was described.

Since the introduction of an executive letter EL (91) 127 by the NHS in 1991 described SCA to support prescribing between hospitals and GPs [ 19 ], several problems have marred the integration of SCA into primary care, and in 2017, the British Medical Association (BMA) stated that shared care is still not working effectively [ 20 ]. General practitioners have expressed concern about poor communication between primary and secondary care, lack of follow-up and monitoring and the medico-legal responsibilities for the prescriber when they accept shared care [ 16 , 21 , 22 , 23 ]. After 30 years, EL (91) 127 has been superseded by the new national guidance released in 2018 for England [ 24 ]. The guidance was designed to overcome the challenges of shared care that have been exhibited in the healthcare system over the last 30 years [ 21 ]. The document has described a role for the pharmacist in general practice in supporting joint working and collaboration to ensure that primary care prescribers have access to information on new or less familiar medicines and how they can support the introduction of medicines into primary care [ 21 ]. Evidence indicates that pharmacists have a significant role in medicine optimisation and improving safe and effective medication use in primary care [ 25 ]. In addition, the literature has shown that pharmacists in general practice are increasingly playing a central role in managing medicines [ 26 ], such as setting up systems for safe monitoring and prescribing high-risk medicines such as direct oral anticoagulants, lithium, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) prescribing and medicine safety requirement in general practice. With the support of government initiatives to increase the number of pharmacists in general practice to support new models of care, the pharmacist could be seen as a vital component in bridging the transfer of care from secondary to primary care settings [ 4 , 27 , 28 ]. This paper aims to review the literature on the role of a pharmacist in general practice with regard to SCA support, their roles and identify the potential benefits, barriers and facilitators to their potential integral role.

This study aimed to identify activities and assess the interventions provided by pharmacists in primary care on SCA provision. The specific objectives were to determine the following:

The types of interventions/activities being provided by pharmacists in supporting SCA in a general practice setting

The effectiveness of these interventions/activities on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) for patients, to consider the impact of clinical pharmacist supporting shared care agreement in a general practice setting.

Study registration

The review protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register for Systematic Review (PROSPERO database; registration number CRD42020165363). The review was guided by the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [ 29 ]. The reporting of the review complies with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement and checklist (refer to supplementary information S 2 and S 3 ) [ 30 ].

Eligibility criteria for study inclusion

The search was focused on locating studies eligible for inclusion or excluded based on the criteria below.

Inclusion criteria

The following are the inclusion criteria:

Only primary studies (qualitative, quantitative and mixed studies)

Studies which have tested an intervention and/or have obtained views of stakeholders (pharmacists, GPs, medical specialists, practice staff and patients) related to SCA in the primary care setting

Studies in which a pharmacist has input within a primary care setting to provide non-dispensing care

Exclusion criteria

The following are the exclusion criteria:

Studies in which the intervention has been provided only in secondary or tertiary care settings (hospitals, specialist clinics and national and regional specialist centre)

Studies written in a language other than English

Studies presented as editorials, protocols and commentaries

Information sources and search strategy

Specific search strategies were developed with expert information specialists and included broad and narrow, free-text and thesaurus-based terms. The term pharmacist was used as a general term to allow greater scope to find multiple roles provided by pharmacists, which included prescribers. Boolean operators and truncation were used to ensure we maximised our search strategy. The following eleven databases were systematically searched from date of inception to November 2021: Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED®) (1985 to 07.11.2021) Platform: Ovid®; Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL®) (1950 to 07.11.2021) Platform: EBSCO®; Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) (accessed on 07.11.2021) Platform: Wiley® online library; Excerpta Medica database (EMBASE®) (1974 to 07.11.2021) Platform: Ovid®; EMCARE® (1995 to 07.11.2021) Platform: Ovid®; Google Scholar (accessed on 07.11.2021) Platform: Google UK®; Healthcare Management Information Consortium (HMIC®) (1979 to November 2021) Platform: Ovid®; Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE®) (1946 to 07.11.2021) Platform: Ovid®; PsycINFO®, Psychology and Behavioural Sciences Collection, Health Business Elite, Biomedica Reference Collection: Comprehensive Library, Information Science & Technology Abstracts (1967 to 07.11.2021) Platform: EBSCOhost®; and Scopus (2004 to 07.11.2021) Platform: Elsevier, Web of Science® Core Collection (1970-07.11.2021) Platform: Clarivate Analytics®. The search was adapted according to the respective database-specific search tools. It was searched using a combination of Medical Subject Heading terms (MeSH) where available, free-text search terms and Boolean operators. Refer to supplementary information S 1 ‘Search terms’ for the specific detail of the search used for each database. Search results in languages other than English were noted, but for practical reasons, only search results in English or translated into English were included in this review. In an effort to identify unpublished studies, a search of grey literature was performed ( http://www.opengrey.eu/ on 07.11.2021) to identify studies not indexed in the databases listed above. The term grey literature in this paper refers to sources used to describe a wide range of information produced outside of traditional publishing and distribution channels and which is often not well represented in indexing databases.

Data collection and analysis

All references from database search were downloaded into EndNote® X8.2 [ 31 ] reference manager, which was used to collate and remove duplicate records, to screen titles and abstracts and to store the full text of retrieved studies. Citations from OpenGrey could not be uploaded to EndNote® reference manager and therefore were uploaded to a Microsoft Excel® 2016 spreadsheet. Duplicate citations were removed by the automatic de-duplicating option in EndNote®X8.2 and were supplemented by hand-searching. Two researchers (NI and CH) examined the titles and abstracts of all eligible articles according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria listed above. References to be screened were allocated into groups and was divided into ‘include’, ‘exclude’ and ‘potential’ groupsets. The full-text articles of any abstracts classified as potentially meeting the inclusion criteria were retrieved and analysed independently by two authors (NI and CH) against the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria with differences between reviewers resolved by consensus. The principal authors of all included papers were contacted to explore the potential for any studies considered vital to them that may have been missed in the search strategy. A data extraction form from the Cochrane collaboration was utilised to extract data from eligible papers [ 32 ]. Raw data from quantitative studies were extracted onto Microsoft Excel® 2016 spreadsheet. If data could not be pooled for meta-analysis, the plan was to undertake a narrative synthesis of results. The qualitative data synthesis methodology was decided upon after the quantity, quality, conceptual richness, and contextual thickness of the qualitative studies were determined. The intended results and data synthesis were to be conducted by authors NI and CH independently to assure the data extraction integrity.

The Mixed Method Appraisal Tool (MMAT) 2018 version was used to appraise and describe the methodological quality of included quantitative, qualitative and mixed-method studies. A pilot test of two articles was conducted to ensure consistent interpretation between the two authors (NI and CH). Discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consensus with the research team. If further information was required to appraise a particular study, an attempt was made to contact the authors by phone or email. Quality scores will be calculated using the MMAT tool. However, this did not solely determine if studies were of “low” or “high” quality, as a descriptive summary using MMAT criteria was considered [ 33 ]. If a study received a low score, it was compared with those with a higher score (higher quality studies) to consider if this modifies the outcome and interpretation of our synthesis.

The database search yielded 7727 citations. After duplicates were removed, the database search identified 3908 citations. Based on the title and abstract information, 3844 citations were ‘excluded’, leaving 64 citations identified as ‘potentially relevant’ articles requiring a full-text article text review. In addition to the 3908 citations that were yielded by the databases, 1336 additional citations were retrieved from http://www.opengrey.eu/ and were screened separately as they could not be uploaded onto EndNote® X8.2 [ 31 ] reference manager. After screening, no pertinent articles that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were extracted from grey literature sources.

On the examination of the full text of the 64 studies in the ‘potentially relevant’ category, no publications addressing evidence to identify activities and to assess interventions provided by pharmacists in primary care on SCA provision were identified (see Table 1 , which includes a tabulated list of the 64 excluded studies along with reasons for exclusion, with some articles having more than one reason for exclusion). Out of the 64 excluded studies, one study (a conference proceeding) could not be found, and an attempt was made to contact the author to obtain further information (full set of results). The author did not respond; hence, this article was excluded from our review as the reviewers could not assess the eligibility based on the information from the abstract. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) flow chart (Fig. 1 ) shows the identification, screening and selection of papers for this review. There were no included studies for which to assess the risk of bias or to apply for evidence synthesis.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) flow chart

This paper aimed to systematically assess the pharmacist’s role in general practice in supporting the implementation of SCA in primary care. No articles met our inclusion criteria. Several studies have tried to define the role of pharmacists in general practice, but the working definition has not been defined by healthcare organisations or the research community [ 98 , 99 ]. Another reason for there to be no studies available is because the GP pharmacist’s role is still a relatively new role in healthcare and little existing literature in role evolution is available [ 100 ].

Comparison with other studies

There is an agreement in the literature that the pharmacist role is developing at pace within the general practice setting and recent international systematic reviews and meta-analyses demonstrate positive effects on medication use and clinical outcomes [ 99 , 101 ]. Pharmacists integrated into general practice teams can perform a variety of roles. This includes direct patient care, medicines reconciliation and education to members of the healthcare team and in the detection and resolution of medication-related problems [ 102 , 103 , 104 ]. A recent review of the impact of integrating pharmacists into primary care teams on health systems indicators on healthcare utilisation by Hayhoe et al. did highlight the activities provided by pharmacists in general practice. Still, it failed to discover activities to support SCA in the published literature [ 105 ]. Internationally, other terminologies and contexts vary, giving one example being collaborative care agreements by Stuhec et al. in Slovenia [ 106 , 107 , 108 , 109 ]. The focus has been aimed in this international context as clinical pharmacists share a role within their own heterogeneous setting and sharing this with various physicians in managing a patient with chronic conditions, not necessarily in the same setting such as GP surgery in the UK where the GP is seen anecdotally as the main gatekeeper and first point of contact for all medication issues related to the patient. The observational studies by Stuhec et al. have focused on older patient and psychiatric patients. Further research would be required to homogenise and formalise an internationally recognised term for shared care agreements.

The most recent Cochrane systematic review, which assessed the effectiveness of shared care across the interface between primary and speciality care in the management of long-term conditions, did not consider models of integrating care between pharmacists and primary care physicians [ 18 ]. The authors of the Cochrane review stated that this limited its generalisability to all types of collaborative care due to the contextual specificity. The review did note that several other models of shared or collaborative care should be considered for review. This systematic review has highlighted that the model of care involving a pharmacist in primary care supporting SCA is not currently present in the literature and should be considered for further investigation.

Implications of the review findings on clinicians and decision-makers in healthcare and future studies

The changing needs of the population make it increasingly important that the patient’s multiple needs are met in a well-coordinated way. To respond effectively to these changing needs, healthcare teams need to utilise the skills available across our healthcare teams. To help alleviate these pressures, it has been recommended that the NHS should maximise the opportunities offered by pharmacists [ 9 , 110 , 111 ]. Pharmacists can take on significant amounts of work currently done by GPs and other staff in general practice [ 111 ]. To explore whether shared care management could be implemented successfully by the pharmacist in general practice, we need to understand the relevant and important pharmacist related barriers and facilitators concerning the implementation of this role. The influence of these factors needs to be recognised and considered and how this can inform further research into this area.

Decision-making

Collaboration between pharmacists and the healthcare team is of paramount importance, and understanding the skills of multiple healthcare professionals will help support an integrated system [ 112 ]. We need to understand the role in which pharmacists will support SCA and how general practitioners are willing to integrate pharmacists within this process. A finding from earlier research has shown that general practice has a positive experience of pharmacist recommendations in a range of conditions [ 113 , 114 , 115 ]. However, how would this apply to SCA when patients and healthcare staff need to understand the role of the pharmacist and agree to the SCA? Would patients accept pharmacists undertaking this new role within the general practice?

Funding and workload

General practice continues to be concerned with the inappropriate funding associated with supporting shared care medication [ 21 ]. Commissioners have always stated that the funding of specialist’s drugs has been agreed so cost should not be an issue. General practitioners have expressed concerns that the additional workload required to support the integration of specialised medication is a factor they believe has not been appreciated [ 116 ]. This has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has seen a rise in how general practice is expected to manage care which would typically be carried out in a hospital setting which in turn has contributed to a growing workload in primary care [ 117 ]. Previous studies have suggested that the impact of practice-based pharmacists will not be on workload but quality and safety [ 118 ]. It is reasonable to ask whether GPs would support pharmacists taking on this role without appropriate funding and whether this intervention will reduce workload in general practice.

Working definition and liability

We need to consider a working definition of the practice pharmacist role in shared care. The differences in pharmacists’ primary care roles have been identified in the international literature. The lack of clarity and knowledge of this primary care role can negatively affect their potential integration into the primary care team [ 119 ]. The knowledge, skills and attitudes required to support SCA should be made readily available to practice pharmacists, primary care teams and the general public. This would enable SCA management to be developed and applied nationally across primary care. The rapid emergence of new professional roles for pharmacists also means that arrangement in respect of liability needs to keep up with the changing nature of pharmacy practice within this more complex intervention.

This empty review can act as a platform to inform policymakers in healthcare that there is a lack of robust evidence that evaluates the role and potential value of pharmacists supporting SCA in general practice. Healthcare systems must seek out the best possible evidence to support patients within this new healthcare environment. However, the absence of research in this area does not justify the rejection of this intervention [ 120 ]. As the role is relatively new, there is still work to be done to develop the evidence base of pharmacists working in general practice to support SCA and the benefits of this role within the healthcare system.

Limitations

A limitation of this review is that the search strategy included a literature search of articles only in the English language. Other articles may have been published on pharmacists supporting SCA in general practice in non-English journals. Personal commentaries, blogs and opinion pieces were excluded from this systematic review due to the research design. This may have excluded observations that are occurring in general practice but have not been critically appraised. Another limitation is that the term SCA may be used as an alternate term from an international perspective. Despite the use of 12 healthcare-related bibliographical databases and the extensive use of keywords to maximise the sensitivity of relevant studies, after removal of duplicates, this yielded a low number of citations of titles and abstracts, another limitation. This systematic review used database word stock to establish standard search terms; however, it cannot be discounted that this may not have retrieved all articles relating to this intervention. Another limitation that needs to be considered is that abstracts from conference proceedings were not included in the synthesis, which could account for the empty return due to the high evidence bar for the systematic review.

This systematic review identified no eligible studies on the interventions provided by a pharmacist in supporting SCA in general practice. It is not possible to formulate what the role pharmacists can play in supporting SCA in general practice based on scientific evidence. There is an urgent need for studies that identify, observe and evaluate GP-based pharmacists’ roles concerning SCA that currently occur in clinical practice. Comparing and contrasting each general practice’s approach will ensure the development of a consensus for the role of GP pharmacists on SCA based on the current SCAs occurring in general practice, and how to implement this intervention consistently. The role of the pharmacist is expanding in general practice, and interventions which prove beneficial for patients and the healthcare system are required to meet the ever-changing demand in healthcare and to ensure that these new interventions follow the evidence. This empty systematic review serves as a starting point for further clinical research in this area.

Availability of data and materials

We provide all supporting data in the manuscript in Fig. 1 , and Table 1 , Search Strategy S 1 , PRISMA statement (S 2 ) and abstract checklist (S 3 ).

Abbreviations

Shared care agreement

Health-related quality of life

Medical Subject Heading terms

- Long-term conditions

National Health Service

British Medical Association

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Mixed Method Appraisal Tool

High-level commission on health employment and economic growth. Working for health and growth: investing in the health workforce. World Health Organization. 2016. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/250047/9789241511308-eng.pdf?sequence=1 . Accessed 03 Aug 2020.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World population ageing 2019 (ST/ESA/SER.A/444): United Nations; 2020. https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/files/documents/2020/Jan/un_2019_worldpopulationageing_report.pdf . Accessed 03 Aug 2020

Book Google Scholar

Campbell J, Dussault G, Buchan J, Pozo-Martin F, Guerra Arias M, Leone C, et al. A universal truth: no health without a workforce. Forum Report 2013, Third Global Forum on Human Resources for Health, Recife, Brazil. Geneva: Global Health Workforce Alliance and World Health Organization; 2013. https://www.who.int/workforcealliance/knowledge/resources/GHWA-a_universal_truth_report.pdf?ua=1 . Accessed 10 Aug 2020

Google Scholar

NHS England, Public Health England, Care Quality Commission, Monitor, NHS Trust Development Authority, Health Education England. NHS five year forward view: NHS England; 2014. https://www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/futurenhs/ . Accessed 10 Aug 2020

Rosen R. Delivering general practice with too few GPs: Nuffield Trust; 2019. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/files/2019-10/general-practice-without-gps-v2.pdf . Accessed 14 Aug 2020

Jones R, Jones R, Newbold M, Reilly J, Drinkwater R, Stoate H. The future of primary and secondary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63:379–82. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp13X669400 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Scally G, Jacobson B, Abbasi K. The UK’s public health response to covid-19. BMJ. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1932 .

Sampson R, Cooper J, Barbour R, Polson R, Wilson P. Patients’ perspectives on the medical primary-secondary care interface: systematic review and synthesis of qualitative research. BMJ Open. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008708 .

Naylor C, Alderwick H, Honeyman M. Acute hospitals and integrated care: from hospitals to health systems: King’s Fund; 2015. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field_publication_file/acute-hospitals-and-integrated-care-march-2015.pdf . Accessed 26 Aug 2020

Cresswell A, Hart M, Suchanek O, Young T, Leaver L, Hibbs S. Mind the gap: improving discharge communication between secondary and primary care. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjquality.u207936.w3197 .

Epstein RM. Communication between primary care physicians and consultants. Arch Fam Med. 1995;4:403–9.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Drummond N, Abdalla M, Buckingham JK, et al. Integrated care for asthma: a clinical, social, and economic evaluation. Grampian asthma study of integrated care (GRASSIC). BMJ. 1994;308:559–64. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.308.6928.559 .

Integrated care for diabetes: a clinical, social and economic evaluation. Diabetes integrated care evaluation team. BMJ. 1994;308:1208–12. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.308.6938.1208 .

Midlands Therapeutics Review and Advisory Committee. Independent review of medicines for primary care. http://ccg.centreformedicinesoptimisation.co.uk/mtrac/ . Accessed 03 Aug 2020.

Hickman M, Drummond N, Grimshaw J. A taxonomy of shared care of chronic disease. J Public Health Med. 1994;16:447–54.

Horne R, Mailey E, Frost S, Lea R. Shared care: a qualitative study of GPs’ and hospital doctors’ views on prescribing specialist medicines. Br J Gen Pract. 2001;51:187–93.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Specialist Pharmacy Service. RMOC work programme: NHS England; 2020. https://www.sps.nhs.uk/topics/?with=rMOc . Accessed 03 Mar 2020

Smith SM, Cousins G, Clyne B, Allwright S, O’Dowd T. Shared care across the interface between primary and specialty care in management of long term conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004910.pub3 .

National Health Service Management Executive. Responsibility for prescribing between hospitals and GPs. London: NHS Management Executive; 1991.

British Medical Association. Primary and secondary care interface guidance. https://www.bma.org.uk/collective-voice/committees/general-practitioners-committee/gpc-current-issues/nhs-england-standard-hospital-contract-guidance-2017-2019/primary-and-secondary-care-interface-guidance . Accessed 03 Mar 2020.

Shared care protocols – have they had their day? Drug Ther Bull. 2017;55:133 https://dtb.bmj.com/content/55/12/133 . Accessed 03 Mar 2020.

Wilcock M, Rohilla A. Three decades of shared care guidelines: are we any further forward? Drug Ther Bull. 2020; https://dtb.bmj.com/content/58/5/67 . Accessed 03 Mar 2020.

Crowe S, Cantrill JA, Tully MP. Shared care arrangements for specialist drugs in the UK: the challenges facing GP adherence. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2009.035857 .

NHS England. Responsibility for prescribing between primary & secondary/tertiary care; 2018. https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/responsibility-for-prescribing-between-primary-and-secondary-tertiary-care/ . Accessed 03 Aug 2020

Tan EC, Stewart K, Elliott RA, George J. Pharmacist services provided in general practice clinics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2014:608–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2013.08.006 .

Wood S. Safer prescribing and monitoring of high-risk medicines. Prescriber. 2020;31(4):10–5.

Article Google Scholar

NHS. The NHS long term plan; 2019. https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/ . Accessed 03 Mar 2020

Petty D. Clinical pharmacist roles in primary care networks. Prescriber. 2019;30(11):22–6.

Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.0 (updated July 2019). Cochrane; 2019. https://training.cochrane.org/cochrane-handbook-systematic-reviews-interventions . Accessed 05 May 2020.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535 .

Clarivate Analytics. EndNote. Version X8.2. Philadelphia: Clarivate Analytics; 2018.

Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). Data collection form. In: EPOC Resources for review authors: Cochrane; 2017. https://epoc.cochrane.org/resources/epoc-resources-review-authors . Accessed 04 Mar 2020.

Hong QN, Pluye P, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), version 2018. Registration of Copyright (#1148552), Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada. Available at: - http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf . Accessed 12 April 2022

Adams B. NHS alliance: The evolution of primary care. Prescriber. 2015;26(3):32–4. Available: - https://wileymicrositebuilder.com/prescriber/wpcontent/uploads/sites/23/2015/12/NHS-Alliance-the-evolution-of-primary-care.pdf . Accessed 12 Apr 2022.

Agyapong VI, Conway C, Guerandel A. Shared care between specialized psychiatric services and primary care: the experiences and expectations of consultant psychiatrists in Ireland. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2011;42(3):295–313. https://doi.org/10.2190/2FPM.42.3.e .

Al-Alawi K, Al Mandhari A, Johansson H. Care providers' perceptions towards challenges and opportunities for service improvement at diabetes management clinics in public primary health care in Muscat, Oman: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-3866-y .

Alhabib S, Aldraimly M, Alfarhan A. An evolving role of clinical pharmacists in managing diabetes: Evidence from the literature. Saudi Pharm J. 2016;24(4):441–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2014.07.008 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Ali S, Smith TL, Mican L, Brown C. Psychiatric providers' willingness to participate in shared decision-making when prescribing psychotropic medications. J Pharm Pract. 2013;26(3):334. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F8755122515578288 .

Aljumah K, Hassali MA. Impact of pharmacist intervention on adherence and measurable patient outcomes among depressed patients: A randomised controlled study. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0605-8 .

Almunef M, Mason J, Curtis C, Jalal Z. Management of chronic illness in young people aged 10-24 years: A systematic review to explore the role of primary care pharmacists. Arch Dis Child. 2019;104(7):e2.39–e2. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2019-nppc.44 .

Alshehri AA, Cheema E, Yahyouche A, et al. Evaluating the role and integration of general practice pharmacists in England: a cross-sectional study. Int J Clin Pharm. 2021;43:1609–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-021-01291-6 .

Anderson K, Freeman C, Rowett D, Burrows J, Scott I, Rigby D. Polypharmacy, deprescribing and shared decision-making in primary care: the role of the accredited pharmacist. J Pharm Pract. 2015;45(4):446–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/jppr.1164 .

General Practitioner/pharmacy interface a local initiative Pharm J. 1994;253(6812):574.

The role of pharmacists in primary care groups (PCGs): a strategic approach. Pharm J. 1999;262(7038):445–6.

Pharmacy in a new age: the role of government. Pharm J. 1995;255(6863):1995.

Shared care addiction scheme starts. Pharm J. 2003;270(7252):782.

Ashcroft DM, Clark CM, Gorman SP. Shared care: A study of patients’ experiences with erythropoietin. Int J Pharm Pract. 1998;6(3):145–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-7174.1998.tb00930.x .

Bains S, Naqvi M, West A. S126 The pharmacist-led accelerated transfer of patients to shared care for the monitoring and prescribing of immunomodulatory therapy during covid-19. Thorax. 2021;76:A75. https://thorax.bmj.com/content/76/Suppl_1/A75.2 .

Bajramovic J, Emmerton L, Tett SE. Perceptions around concordance–focus groups and semi-structured interviews conducted with consumers, pharmacists and general practitioners. Health Expect. 2004;7(3):221–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-7625.2004.00280.x .

Barnes E, Ashraf I, Din A. New roles for clinical pharmacists in general practice. Prescriber. 2017;28(4):26–9. https://wileymicrositebuilder.com/prescriber/wpcontent/uploads/sites/23/2017/04/Pharmacist-new-roles-EB-edit-AC-made-lsw.pdf .

Bellingham C. How to improve medicines management at the primary/secondary care interface. Pharm J. 2004;272(7287):210–1.

Berendsen AJ, de Jong GM, Meyboom-de Jong B, Dekker JH, Schuling J. Transition of care: experiences and preferences of patients across the primary/secondary interface–a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9(1):62. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-9-62 .

Bojke C, Philips Z, Sculpher M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of shared pharmaceutical care for older patients : RESPECT trial findings. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60(570):e20–7. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp09X482312 .

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

British National Association of Health and Trusts. NAHAT Update: asthma care - the challenge ahead. Conference 1994.

Cain RM, Cain RM. The physician-pharmacist interface in the clinical practice of pharmacy. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40(12):2240–2. https://doi.org/10.1345/aph.140048 .

Carrington I, McAloon J. Why shared-care arrangements for prescribing in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder may not be accepted. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2018;25(4):222–4.

Chana N, Porat T, Whittlesea C, Delaney B. Improving specialist drug prescribing in primary care using task and error analysis: an observational study. Br J Gen Pract. 2017;67(656):e157–67. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp17x689389 .

Chartrand M, Maheu A, Guenette L, Martin E, Moisan J, Gregoire JP, Lauzier S, Blais L, Perreault S, Lalonde L. Implementation and evaluation of pharmacy services through a practice-based research network (PBRN). Journal of Population Therapeutics and Clinical Pharmacology. 2013;20(3):e272–3.

Cox WM. Evaluation of a shared-care program for methadone treatment of drug abuse: An international perspective. Journal of Drug Issues. 2002;32(4):1115–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F002204260203200407 .

Crowe S, Tully MP, Cantrill JA. The prescribing of specialist medicines: what factors influence GPs’ decision making? Family practice. 2009;26(4):301–8.

Crowe S, Cantrill JA, Tully MP. Shared care arrangements for specialist drugs in the UK: the challenges facing GP adherence. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(6):e54.

Duggan C, Beavon N, Bates I, Patel S. Shared care in the UK: Failings of the past and lessons for the future. Int J Pharm Pract. 2001;9(3):211–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-7174.2001.tb01051.x .

Fearne J, Grech L, Inglott AS, Azzopardi LM. Development and evaluation of shared paediatric pharmaceutical care plan. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40(1):263–4.

Finch E, Ford C [ed]. Shared care at the primary and secondary interface: GPs and specialist drug services. Drug misuse and community pharmacy 2002 1st Edition. eBook ISBN 9780429229848.

Grixti D, Vella J, Fearne J, Grech L, Pizzuto MA, Serracino-Inglott A. Development of shared care guidelines in rheumatology. Int J Clin Pharm. 2014;36(4):850.

Gu Y, Humphrey G, Warren J, Tibby S, Bycroft J, editors. An Innovative Approach to Shared Care–New Zealand Pilot Study of a Technology-enabled National Shared Care Planning Programme. Health Informatics New Zealand Conference; 2012

James O, Cardwell K, Moriarty F, Smith SM, Clyne B, on behalf of the General Practice Pharmacist (GPP) Study Group. Pharmacists in general practice: a qualitative process evaluation of the General Practice Pharmacist (GPP) study. Family Practice. 2020;37(5):711–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmaa044 .

Johnson C. Adult attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) clinic: A collaboration between psychiatry, primary care and pharmacy to improve access, care experience and affordability. JACCP. 2018;1(2):318.