The Effect of Market Orientation on Marketing Performance: A Case Study on Commercial Bank of Ethiopia

Journal title, journal issn, volume title, description, collections.

Ideas and insights from Harvard Business Publishing Corporate Learning

Market Orientation: Why It Matters for Leaders at all Levels

It can be tempting, very tempting. You’re focused on your job, your department, your team, and you just have so much to do. So you leave worrying about your organization’s market orientation—understanding who your customers are, what value you create for them, why they choose your organization, what your competition’s doing—to someone else. You have enough on your plate already, so you delegate accordingly. Need to know basis only , you tell yourself. And maybe you don’t feel you need to know.

But you should.

Leaders at all levels and functions must build their business acumen . And fundamental to business acumen is identifying your organization’s market orientation.

Why market orientation matters

When you know your organization’s customers and what they value, you’re able to make smarter choices in your role. To demonstrate this, a product manager, for instance, might come up with a new product feature that delights customers. Another case could be an HR professional who proposes new benefits that help their organization out-recruit the competition and close critical skill gaps that meet an emerging market need.

When you’re fluent in the language of business – your business – you’re better equipped to persuade decision makers to rally around your plans.

As a leader, you often need to gain approval for your ideas or build coalitions in support of your strategy . When you’re fluent in the language of business – your business – you’re better equipped to persuade decision makers to rally around your plans. And when you’re looking to level up in your career, having solid business acumen can carry as much weight as your domain expertise.

Know your organization’s story

Fundamental to building your market orientation savvy is knowing your organization’s story. The elements of this story include:

- Who your customers are

- What customers value most about your offerings

- How you bring those offerings to your customers

- What differentiates you from your competitors

- How your organization makes money by doing all this

Where will you find your organization’s story? By knowing the business model. All organizations — from small businesses to scrappy startups to Fortune 500 companies — need a business model to succeed. Your organization may not have a document explicitly labeled as its business model, but the elements that comprise your business model should be there for the asking — including your organization’s story.

Key elements of your organization’s story

The first part of your organization’s story covers who your customers are and how you satisfy their needs. The story should also include:

- How your organization attracts and retains customers,

- how it grows its base,

- and how it entices customers to buy more of its products and services.

Your value proposition: Critical for market orientation

Your value proposition may be the most important part of the business model to get right. That was the thinking of Mark Johnson, Clayton Christensen, and Henning Kagermann in “ Reinventing Your Business Model ,” a timeless article that appeared in Harvard Business Review in 2008. In defining the value proposition, they wrote:

A successful company is one that has found a way to create value for customers – that is, a way to help customers get an important job done. By “job” we mean a fundamental problem in a given situation that needs a solution.

How critical is it to get the value proposition right?

CBInsights analyzed over 100 startup postmortems and found that 35% of failed startups cited “lack of market need” as one of the reasons for their failure. In other words, they hadn’t found a way to create value for customers.

35% of failed startups cite “lack of market need” as one of the reasons for their failure. In other words, they didn’t find a way to create value for customers.

Of these failed startups, 20% also cited losing to their competition. Your organization’s business model may not directly call out how it’s different from your competitors. However, the value proposition can help you understand why customers choose you over others in your category. As you increase your market orientation, it’s important to know who your competitors are and where you win or lose against them.

A business model should also include information about the channels you use to reach and serve customers, as well as what your customers are willing to pay for your offerings.

Once you understand your organization’s business model, you’ll gain a clear view of your market orientation. This new focus will help you expand your business acumen and increase the value you provide to your organization.

And not to worry: you’ll still get things done. Now, though, you’ll understand why you do what you do — and who benefits from it.

Let’s talk

Change isn’t easy, but we can help. Together we’ll create informed and inspired leaders ready to shape the future of your business.

© 2024 Harvard Business School Publishing. All rights reserved. Harvard Business Publishing is an affiliate of Harvard Business School.

- Privacy Policy

- Copyright Information

- Terms of Use

- About Harvard Business Publishing

- Higher Education

- Harvard Business Review

- Harvard Business School

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience. By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

Cookie and Privacy Settings

We may request cookies to be set on your device. We use cookies to let us know when you visit our websites, how you interact with us, to enrich your user experience, and to customize your relationship with our website.

Click on the different category headings to find out more. You can also change some of your preferences. Note that blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience on our websites and the services we are able to offer.

These cookies are strictly necessary to provide you with services available through our website and to use some of its features.

Because these cookies are strictly necessary to deliver the website, refusing them will have impact how our site functions. You always can block or delete cookies by changing your browser settings and force blocking all cookies on this website. But this will always prompt you to accept/refuse cookies when revisiting our site.

We fully respect if you want to refuse cookies but to avoid asking you again and again kindly allow us to store a cookie for that. You are free to opt out any time or opt in for other cookies to get a better experience. If you refuse cookies we will remove all set cookies in our domain.

We provide you with a list of stored cookies on your computer in our domain so you can check what we stored. Due to security reasons we are not able to show or modify cookies from other domains. You can check these in your browser security settings.

We also use different external services like Google Webfonts, Google Maps, and external Video providers. Since these providers may collect personal data like your IP address we allow you to block them here. Please be aware that this might heavily reduce the functionality and appearance of our site. Changes will take effect once you reload the page.

Google Webfont Settings:

Google Map Settings:

Google reCaptcha Settings:

Vimeo and Youtube video embeds:

You can read about our cookies and privacy settings in detail on our Privacy Policy Page.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 04 October 2023

Market orientation practices of Ethiopian seed producer cooperatives

- Dawit Tsegaye Sisay ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1829-4214 1 ,

- Frans J. H. M. Verhees 2 &

- Hans C. M. van Trijp 2

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 637 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

781 Accesses

1 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Business and management

The practices of market orientation are context-specific. This paper focuses on the concept and practices of market orientation in Ethiopian seed producer cooperatives (SPCs). Based on 44 semi-structured interviews with experts and practitioners (SPC leaders and member farmers), we identify key market orientation elements in the SPCs’ context. Market orientation criteria in the Ethiopian SPC context could meaningfully be grouped into five underlying dimensions: quality of produce, business organization, external orientation, value addition activities, and supplier access. The understanding of market orientation by practitioners, particularly by member farmers, is limited to quality seed production. There is considerable recognition among respondents of the importance of customer orientation in the SPC context. Information on produced seeds, market prices, and profits is considered important. Information on competitors, although recognized by experts as important, is not really gathered by SPCs. Experts believe that the SPC committees should be responsible for information dissemination, but in practice, there is also an important role for the SPC chairman personally. Market-oriented practices in SPCs contribute to increasing employment and productivity and ensuring food security. Policymakers should devise strategies to support SPCs in becoming more market-oriented and successful in their business ventures. Specific market orientation practices by SPCs are discussed in detail.

Similar content being viewed by others

A scoping review of market links between value chain actors and small-scale producers in developing regions

Lenis Saweda O. Liverpool-Tasie, Ayala Wineman, … Ashley Celestin

Sustainability standards in global agrifood supply chains

Eva-Marie Meemken, Christopher B. Barrett, … Jorge Sellare

Growers’ perceptions and attitudes towards fungicide resistance extension services

Toto Olita, Michelle Stankovic, … Mark Gibberd

Introduction

Market orientation lies at the heart of marketing theory (Ozkaya et al., 2015 ) and is seen as a key contributor to organizational performance in terms of profitability, sales growth, return on investment, customer perceived quality, customer satisfaction and loyalty, employee’s satisfaction, esprit de corps, and organizational commitment (Kirca et al., 2005 ; Kohli and Jaworski, 1990 ; Maydeu-Olivers and Lado, 2003 ; Narver and Slater, 1990 ; Raaij and Stoelhorst, 2008 ).

Empirically, the concept and practices of market orientation and its effect on business’ performance are well-documented for large companies in developed countries (Bhattarai et al., 2019 ; Cano et al., 2004 ; Ellis, 2006 ; Harris and Ogbonna, 2001 ; Homburg and Pflesser, 2000 ; Kirca et al., 2005 ; Langerak, 2001 ). The general finding is that, in developed countries with mature economies characterized by the prevalence of buyer’s markets, stable growth, and intense competition, market orientation positively contributes to the company’s sustainable competitive advantage (Ellis, 2005 ). Market-oriented businesses can satisfy the expressed and latent needs of their customers (Farrell, 2000 ; Harris and Ogbonna, 2001 ; Homburg and Pflesser, 2000 ; Inoguchi, 2011 ; Langerak, 2001 ).

As a positive market orientation-performance relation in large businesses exists, it is postulated that the market orientation practices also are applicable to and profitable for small businesses (Bamfo and Kraa, 2019 ; Blankson and Stokes, 2002 ; Verhees and Meulenberg, 2004 ). Although based on relatively few studies, the available evidence suggests that this is indeed the case (Blankson and Cheng, 2005 ; Chao and Spillan, 2010 ; Inoguchi, 2011 ; Pelham, 2000 ; Renko et al., 2009 ).

Studies regarding market orientation practices in the context of developing and emerging (D&E) economies are scarce (Coffie et al., 2020 ; Mahmoud, 2011 ). Several scholars have urged for exploring the tenability of marketing theory taking into consideration the specific situation of D&E economies (e.g., Burgess and Steenkamp, 2006 ; Sheth, 2011 ). Most D&E economies are highly local and suffer from inadequate infrastructure, lack of access to technologies, and chronic resource shortages (Sheth, 2011 ). Such challenges are highly determinant, particularly for small businesses. The direct transferability to the D&E economies of the market orientation theories and practices which were developed on the assumptions of the Western world might be difficult (Burgess and Steenkamp, 2006 ). The context of D&E economies differs considerably from high-income countries’ (HICs) context. The institutional context of D&E economies departs from the assumptions of theories developed in HICs (Wright et al., 2005 ).

Because of the wide technical, managerial, financial, political, socio-economical, and infrastructural differences between large businesses in developed nations and small businesses in D&E economies, market orientation thinking, and practices may need to be adjusted to the context of small businesses in D&E economies (Burgess and Steenkamp, 2006 ; Sheth, 2011 ). It should be considered the specific context in the implementation of the market orientation practices. Moreover, understanding the unique situation of D&E economies may give fertile ground to develop new perspectives and practices in the marketing discipline (Burgess and Steenkamp, 2006 ; Sheth, 2011 ). For example, competitor orientation is considered one of the key components of market orientation that significantly contributes to firm performance in HICs (Narver and Slater, 1990 ). However, studies in the D&E economies show that competitor orientation has a limited contribution to the livelihood performance of Ethiopian pastoralists (Ingenbleek et al., 2013 ). This indicates that the practices of market orientation and their influence on performance may vary in D&E economies which are characterized by specific cultural contexts. Thus, specific market orientation practices of D&E economies need to be understood for the proper implementation of the concept of market orientation. Therefore, there is a need to conduct more research in diverse cultures and contexts to boost conviction in the nature and power of market orientation (Burgess and Steenkamp, 2006 ; Narver and Slater, 1990 ).

Specific to the Ethiopian context, we have limited information about the implementation of market orientation (Oduro and Haylemariam, 2019 ). our understanding is partial regarding how market orientation is interpreted and practiced in the context of small agricultural marketing cooperatives in Ethiopia. Our case study focuses on the Ethiopian seed sector with specific consideration for seed producer cooperatives (SPCs) and how the concept of market orientation is understood and applicable in their context. We consider SPCs as a case of small agricultural marketing cooperatives in D&E economies. Therefore, the main aims of this paper are: (1) to explore the understanding and interpretation of market orientation in the context of small agricultural marketing cooperatives taking Ethiopian SPCs as a case, and (2) to make an inventory of the current practises in the domain of market orientation components proposed by Kohli and Jaworski ( 1990 ).

The structure of the paper is as follows. First, the paper briefly introduces the market orientation concept in general and the evidence of its applicability to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in D&E economies. Next, it describes the context of the study. This is followed by a description of the methodology of the study and a presentation of the results. The paper continues with the conclusion and discussion and ends with suggestions for further research.

Market orientation

Market orientation is defined as the implementation of the marketing concept, which is the cornerstone of the marketing discipline and contributes to long-term profitability (Deshpande and Farley, 2004 ). Narver and Slater ( 1990 ) and Kohli and Jaworski ( 1990 ) studied market orientation empirically in different industries. Market orientation has been approached as a company culture building on three components: orientation on the customer and on competitors, and cross-functional coordination within the company to effectively and efficiently respond to and anticipate the challenges in the external environment (Narver and Slater, 1990 ). In terms of market intelligence functions, market orientation practices involve the generation and dissemination of market intelligence and the responsiveness to such intelligence (Kohli and Jaworski, 1990 ). These two seminal works provided conceptualizations, definitions, and measures of the market orientation constructs.

Market orientation provides a business with a better understanding of its customers, competitors, and environment, which subsequently provides necessary inputs based on which superior business performance can be built (Kirca et al., 2005 ). A market-oriented business is one that successfully applies the marketing concept (create value for customers), which indicates that the key to organizational success is through the determination of the needs of target markets and satisfaction of these needs for profit and/or other objectives (Blankson and Stokes, 2002 ; Deshpande and Farley, 2004 ; Jeong, 2017 ). Market-oriented firms are known for their superior understanding of the expressed and latent needs of existing and potential customers and by their ability to offer solutions to those needs (Amirkhani and Fard, 2009 ; Ellis, 2006 ; Sampaio et al., 2020 ). Market-oriented businesses should focus on customers’ satisfaction and sustainable profits and should also develop close relationships with important customers to gain deeper insight into those customers’ desires (Slater and Narver, 1998 ; Yang, 2013 ). Moreover, they do not only focus on short-term profit, but focus on sustainable profits (e.g. Narver et al., 2004 ). Market-oriented firms are more flexible in their market exit decisions than less market-oriented organizations (Yayla et al., 2018 ). Meta-analysis assessments reveal that market orientation has predominantly positive relationships with various performance measures including profits, sales and market share, customer satisfaction, new product performance, team spirit, and job satisfaction (Cano et al., 2004 ; Kirca et al., 2005 ).

Market orientation in small businesses

The understanding of the concept of market orientation and its implementation practices vary between large companies and SMEs (Hernández-Linares et al., 2020 ). However, market orientation has also a positive impact on the performance of SMEs (Acikdilli et al., 2020 ; Bamfo and Kraa, 2019 ; Kasim et al., 2018 ; Zhang et al., 2017 ). The typical features of SMEs render the implementation of the market orientation concept more challenging than for large companies. This is because SMEs typically do not have specialized functions and departments (under one roof) and are constrained by technical and financial resources. Because of the differences in infrastructure, the availability of and access to resources (skilled labor, finance), the number and type of customers, and the firm’s technological competence, both the processes of information generation and dissemination, as well as the process of coordinated response are more fluid, less structured and possibly less articulated (Blankson and Stokes, 2002 ; Mahmoud, 2011 ; Verhees and Meulenberg, 2004 ). As a result, in SMEs market orientation practices reside much more at the individual level, rather than at the formalized departmental level as in large companies. Studies on the impact of market orientation on SMEs are limited particularly the organizational innovation (Alhakimi and Mahmoud, 2020 ; Didonet et al., 2016 ).

Small businesses have limitations in technical, managerial, and financial capabilities to run their business. Unlike large companies, they do not have marketing specialists to generate information about customers’ needs (preferences) and competition or to make good forecasts. The owner (manager) of the business is largely responsible for marketing, and hence for the survival of the business (Rizzoni, 1991 ). SMEs are constrained by scarce resources and poorly developed management systems to access information (Carpenter and Petersen, 2002 ). Their market intelligence is mostly based on external (personal) contacts with customers and suppliers (Verhees and Meulenberg, 2004 ).

The dissemination of market intelligence provides a shared basis for concerted actions by the different departments (Kohli and Jaworski, 1990 ). For small businesses owned by one individual person, coordination between internal departments is not an issue because the owner makes the major decisions (Inoguchi, 2011 ). Literature supports the omission of the intelligence dissemination component of market orientation for small businesses (Verhees and Meulenberg, 2004 ). Importantly, information dissemination increases employee motivation, which has a direct impact on external market orientation (Ian and Gordon, 2009 ).

Small businesses run by the owner can respond with alacrity and flexibly to market intelligence because decision-making is non-bureaucratic, and the decision-maker is able to oversee the whole production and marketing process (Carson et al., 1995 ; Verhees and Meulenberg, 2004 ). The coordinated response towards the information generated is the key element for successful business performance (Hult and Ketchen, 2001 ). The predominant view is that limited financial and technical resources can hinder small businesses from responding to customers’ needs, particularly in unexpected phenomena such as the covid 19 pandemic (Alekseev et al., 2023 ; Bartik et al., 2020 ). However, some researchers have reported that responding to market intelligence seems to be easier for small businesses compared to larger organizations because of their size (Inoguchi, 2011 ). Besides their limited resources and narrow range of technological competencies, the owner’s (manager’s) technical capabilities also hinder the firm’s response to customer’s needs. The owner often focuses on the efficiency of current operations (Niemimaa et al., 2019 ).

Market orientation in D&E economies

The market situation in D&E economies puts a further challenge on the implementation of market orientation, both in terms of business structures as well as regarding the socioeconomic, cultural, and political contexts (Ho et al., 2018 ). Basic marketing infrastructures such as marketing data, communication availability, electricity, roads, e-banking (e-commerce), and skilled manpower are largely absent or poorly developed in D&E economies (Sheth, 2011 ). In most cases, markets in D&E economies are local, very fragmented, and small. Underperformance of formal institutions, uneven distribution of value added in supply chains, underperformance of spot markets, weak institutional environments, and politically affiliated marketing systems are some of the key limitations in D&E economies (Guo et al., 2019 ). However, despite these bottlenecks, there is rapid economic growth in many developing countries.

The limited technical and managerial capabilities of firms in D&E economies together with poor marketing infrastructure hinder the level of implementation of market orientation. Firms may not have well-organized and structured information-gathering schemes and capabilities, and market intelligence is costly for individual firms to generate. In most cases, market information is generated through secondary data using both formal and informal approaches such as customer surveys, meetings and discussions with customers and trade partners, and analysis of sales reports. Advances in information technology are potentially helpful in generating intelligence (Ngamkroeckjoti and Speece, 2008 ) but require skills and infrastructural facilities. Particularly for small businesses in rural areas of emerging economies, accessing intelligence via advanced technologies is limited. However, the increasing coverage of mobile phones in emerging economies provides a good opportunity to facilitate the decision-making process regarding the type of goods to produce and sales prices (Arinloye, 2013 ). Besides the limited resources available to the companies, the poor infrastructural development hinders firms from responding to customers’ needs. E-banking (e-commerce) is very limited, or even absent in some countries, which makes reaching customers and expanding business troublesome (Asikhia, 2009 ).

However, with all limitations regarding infrastructure development and context-specificity, there are studies that report the positive effect of market orientation on firm performances in the D&E too (Masa’deh et al., 2018 ; Wakjira and Kant, 2022 ). Studies reported a positive relationship between market orientation, innovation, and firm performance (Prifti and Alimehmeti, 2017 ). The positive relationship was also reported from several developing countries, including Brazil (Frank et al., 2016 ), China (Zhang et al., 2021 ); Iran (Salehzadeh et al., 2017 ), and Ethiopia (Wakjira and Kant, 2022 ).

The implementation of market orientation in D&E economies particularly in small businesses is expected to involve unique market orientation practices, beyond those identified in “general” marketing theory. It has context-specific features concerning customers’ needs identification, dissemination of information within the business, and implementation of a coordinated response to the information generated and disseminated.

Obviously, the arguments of the market orientation theories and practices are assumed to be constant and equally applicable in other environmental conditions. However, the context of D&E economies differs considerably from the HICs’ context in which market orientation theory was originally developed (Ellis, 2005 ). Most countries in D&E economies suffer from inadequate infrastructure, lack of access to technologies, and resource shortages (Sheth, 2011 ). The institutional context of D&E economies departs from the assumptions of theories developed (Wright et al., 2005 ). Hence, firms in D&E economies may not be able directly to incorporate and apply the knowledge of marketing that is derived almost exclusively from high-income, industrialized countries (Burgess and Steenkamp 2006 ).

Market orientation of small agricultural producer cooperatives in D&E

The concept of market orientation can also be applied to the context of cooperatives; however, it may take on diverse forms and attributes (Sisay et al., 2017b ; Agirre et al., 2014 ). Studies show that the application of the concept of market orientation in the cooperative context should consider the issue of governance mechanisms and organizational structures of the cooperatives (Benos et al., 2016 ). These unique organizational arrangements of agricultural cooperatives are an area that should be considered while market-oriented strategies are sought (Kyriakopoulos et al., 2004 ). As intense market competition exists, cooperatives should deliver higher value to customers through the implementation of market orientation (Bijman, 2010 ). Hence, they should be market-oriented enterprises to respond to the existing highly competitive markets (Kyriakopoulos et al., 2004 ; Ketchen et al., 2007 ; Agirre et al., 2014 ).

The implementation of the market orientation concept in the cooperative context is highly determined by the economic status where they are operating (developed vs. developing economies) and the specific cultural, organizational and human resource capabilities within the cooperatives. High attention by cooperative management towards the implementation of the marketing concept is also another factor (Agirre et al., 2014 ). Most studies focus on how internal factors (e.g., organizational structure, human resource capacities, etc.) and external factors (e.g., policy framework) affect the implementation of market orientation within the cooperative. Cooperative organizational attributes positively influence the implementation of market orientation (Benos et al., 2016 ). Agirre et al. ( 2014 ) reported the influence of internal organizational factors of the cooperatives (organizational commitment, integration of cooperatives) on the degree of market orientation of the cooperatives.

Studies on the association between market orientation and performance in the agricultural cooperative context are limited. The positive influence of market orientation on the performance of agribusiness cooperatives in Greece is reported by Benos et al. ( 2016 ). They measured the performance of the agribusiness cooperatives in Greece in terms of sales volume, new market entry, and market share (Benos et al., 2016 ). Agirre et al. ( 2014 ) explained the benefits of market orientation for the business performance of the worker cooperative organization of the Mondragon group of Spain. They reported the positive influence of market orientation on cooperative performance in terms of efficiency (i.e., profitability, return on investment) and effectiveness (i.e., growth of sales, growth in the market, growth in profits).

Studies on the market orientation of agricultural cooperatives in D&E are scanty. A study in Rwanda shows that the participation of farmers in cooperatives improves market orientation, resulting in an increase in the share of farm produce sold (Verhofstadt and Maertens, 2014 ). A positive contribution of market orientation to the business unit of cattle milk cooperatives was reported in Indonesia (Al Idrus et al., 2018 ). The success of cooperatives in becoming market-oriented is based on their selected strategies regarding membership, commodities, etc. (Bijman and Wijers, 2019 ).

There are arguments for and against the contribution of market orientation to the performance of agricultural cooperatives in Ethiopia. It is evident that there is a significant difference between cooperatives in Ethiopia regarding service delivery, market orientation, composition, and socio-economic context (Chagwiza et al., 2016 ). The objective of establishing a cooperative is one main determining factor for being a market-oriented business (Subedi and Borman, 2013 ). Most of the agricultural cooperatives in Ethiopia have established the so-called ‘service delivery’ mentality while leaving the key elements of market orientation (Emana, 2009 ). This is related to the lack of market information and the absence of a marketing plan by agricultural cooperatives, as they mainly focus on production. Other studies, however, reported a positive association between market orientation and cooperative performance in Ethiopia, depending on the specific businesses they engage in, such as coffee (Ruben and Heras, 2012 ) and seed (Sisay et al., 2017a ). However, the performance of cooperatives is associated with specific market orientation components, indicating they are partly market-oriented (Sisay et al., 2017b ; Wassie et al., 2019 ). Studies show that Ethiopian seed producer cooperatives are not competitor-oriented, but customer orientation, inter-functional coordination, and supplier orientation contribute to higher business performance (Sisay et al., 2017b ). Studies in Ethiopia on the contribution of market orientation to smallholder farmers and factors affecting market orientation are available, though limited (e.g., Gebremedihin and Jaleta, 2013 ; Ingenbleek et al., 2013 ). However, research on the specific practices of market orientation for agricultural cooperatives is scarce.

Context of the study

Improving agricultural productivity is indispensable, in the aim to increase food supply for a growing population and for improving the economic status of Ethiopia (Hopfenberg and Pimentel, 2001 ). Seed is one of the basic inputs in agriculture and plays a vital role in the sustainable development of the Ethiopian agricultural sector (Alemu, 2011 ). Seed security and food security are linked together with agricultural economic development (Louwaars and de Boef, 2012 ; Thijssen et al., 2008 ). To satisfy the seed demand of farmers, public and private seed companies have been trying to provide quality seeds for farmers. However, they focus only on a few cereal crops, can supply only about 10% of the seed farmers use, and cannot satisfy the diversified seed needs of farmers (Bishaw et al., 2008 ).

In terms of customer demand, farmers’ seed demand varies between locations. Agro-ecological adaptability, sociocultural interest, irrigation facilities, local market demand, technical and financial capabilities, and government regulations are some of the factors that determine farmers’ choice of specific varieties and seeds (Thijssen et al., 2008 ). To satisfy the diversified seed demand of farmers and to contribute to seed security at the local level and beyond, the government and development partners support the establishment and strengthening of SPCs in various parts of the country (Sisay et al., 2017a ). The support aims to promote sustainable local seed businesses so that they become technically well-equipped, professional, market-oriented, and self-reliant in their seed business. SPCs are small seed enterprises and autonomous organizations established by a group of individual farmers from a given locality, organized as agricultural marketing cooperatives. They produce quality seed and become profitable using contractual seed production and direct selling to final customers (Tsegaye, 2012 ). Rural communities, but also other stakeholders, including policymakers, recognize SPCs’ contributions to the seed sector (Alemu, 2011 ). The government of Ethiopia sees a key role in a well-functioning agricultural cooperative sector, with cooperatives being self-sustaining economic enterprises, to support economic growth (ATA, 2012 ).

Seed producer cooperatives are not managed by one person, unlike typical small businesses. Most SPCs have three separate committees with clear roles and responsibilities, although the organizational setup varies. These committees are an executive committee (SPC leaders), a seed quality control committee, and a managerial and financial control committee. Committee members are selected out of the members of the cooperative. Some SPCs do also have other committees such as a marketing committee and a purchasing committee. The executive committee is responsible for managing the overall seed business activities. This committee develops annual budgets, implements bylaws approved by members, hires employees, manages all the resources of the cooperative, searches for market opportunities, accesses agricultural inputs (basic seeds for commercial seed production, fertilizers, crop protection chemicals, farm implements) for members, takes disciplinary actions against members that violate the bylaws and regularly report to the general assembly. The seed quality control committee is responsible for all seed quality-related issues. This committee monitors and controls the quality of the seed at all levels: in the field, during storage, packaging, and transportation. The control committee is responsible for managerial and financial-related issues and is accountable to the general assembly. In the general assembly, members of the SPC participate in decision-making on major issues. The general assembly is nominating, electing, and re-electing committee members.

Although market orientation is seen as an important feature to further develop the seed sector in Ethiopia and has been implemented as a strategic intent of the Ethiopian SPCs, there is a lack of understanding to what extent and in which form this strategic intent has been put into practice. To fill the gap in understanding market orientation practices and experiences within the D&E small marketing cooperative context, we employ a case study approach (Yin 2003 ).

Methodology

The purpose of using the case study method is to emphasize detailed contextual analysis of a limited number of events or conditions to examine contemporary real-life situations (Yin, 2003 ). We used a case study for intensive analysis of a specific situation in the Ethiopian SPCs context as a single case because no detailed information regarding SPCs’ current market orientation practices. The case study offers a rich method for investigating and researching a single case (Widdowson, 2011 ). For context-dependent experiences such as small businesses in D&E, the use of case studies is suggested to investigate the specific phenomenon (e.g. Flyybjerg, 2006 ). Moreover, the use of case studies could generate context-dependent knowledge which is an appropriate form of knowledge base in social sciences (Flyybjerg, 2006 ). This study of Ethiopian SPCs explores the understanding and interpretation of market orientation in the context and takes inventory of current practices in the domain of market orientation components: information generation, information dissemination, and responsiveness to this information. In this section, we describe the study area, case selection, data collection, and data analysis procedures.

Study area and case selection

To ensure adequate coverage of potential heterogeneity in the Ethiopian situation, four SPCs were selected from four regional states in Ethiopia: Amhara region, Oromia region, Southern Nations Nationalities and Peoples region (SNNPR), and Tigray region. These four SPCs vary in terms of their organizational structure, formation history, production potential, seed marketing experience, number of members, marketing strategy and market arrangement, and agroecological conditions. The first SPC is in the northern dryland area of the country. The area is characterized as one of the dryland areas in the country. The SPC is experienced in seed potato and food barley seed production and sells its products to customers (i.e. farmers) in the vicinity and beyond, but most of its seed is sold at the local market. The SPC sometimes sells its seed directly to institutional buyers such as NGOs. In the area, farmers often use a simple bartering system for seed exchange. The cooperative has 33 members and is led by a committee selected from its members. The SPC has nine years of seed production and marketing experience. The SPC is also produce other locally demanded crop varieties. The second SPC is in the northwest highland part of the country. This part of the country is known for its high production potential and its being a food secure area. The SPC produces mainly cereal crop varieties: hybrid maize, tef, and malt barley. Most of the time it sells its products based on a contractual arrangement with public seed enterprises. This cooperative is led by an executive committee along with other supporting committees such as the controlling committee and quality control committee. This SPC has more than eight years of seed production and marketing experience. The third SPC is in the central part of the country. The area has high production potential and better infrastructures (road, electricity, proximity to potential markets, etc.) than most parts of the country. The SPC has been involved in bread wheat, chickpea, tef, and lentil seed production and marketing since 2007. It sells its seeds directly to farmers and institutional buyers. It has good experience in working with researchers in a variety of promotion, demonstration, and dissemination. The SPC is led by an executive committee. Moreover, it has a quality control committee, purchasing committee, and control committee. The fourth SPC is in the southern part of the country and has the potential to produce various crops. Executive committee members are responsible for leading and supervising the cooperative’s seed business activities. It has diversified seed marketing approaches: direct marketing to customers (i.e. farmers) and contractual arrangements with unions. Tef and haricot beans are the main seeds produced and marketed by the cooperative. The cooperative has more than six years of seed production and marketing experience.

Data collection

Primary data were collected from individual interviews to get an inside perspective on opinions, ideas about, and experiences with the concept and practices of market orientation. In-depth face-to-face interviews were conducted with three groups of interviewees: SPC leaders, member farmers, and experts who have knowledge about and experience with the market orientation practices of SPCs.

Interview guides were similar between the different groups of respondents, with the exception that the interview guides for experts were framed normatively as what “should” be done, whereas for practitioners these were framed descriptively in terms of actual practices conducted. Also, the questions for experts referred to SPCs in general (“an SPC”), whereas those for SPC leaders and farmers made explicit reference to their specific SPC (“your SPC”).

Interview guides consisted of two main parts. The first part focussed on understanding and interpretation of the market orientation concept generally, guided by two open-ended questions: (1) “W hen do you consider your (/an) SPC to be market-oriented?” , and (2) “ What activities does your SPC (/should an SPC) do to be market-oriented?” The second part focussed on each of the specific components of market orientation: information generation, dissemination, and responsiveness. Again, first, an open question was asked (e.g., “what kind of information does your (/should an) SPC gather about the market?” ) to allow respondents to express their understanding and experiences in their own words. Then more specific questions were asked for further details (how, from whom, who, etc.) on each of these market orientation practices.

Prior to the interview, respondents were briefed about the purpose of the interview and research, the reason why they were selected, the importance of participation, and the anonymity and confidentiality of the interview (Saunders et al., 2000 ). Before the interview the concept of market orientation was explained to the interviewees, using the following description: “It basically refers to the organization-wide information generation, dissemination, and appropriate response to satisfy customers’ needs.” In the beginning, a few farmer respondents did not have clear opinions about the open-ended questions regarding the meaning of the concept of market orientation. To them, the meaning of the questions was explained at the level of their understanding in terms of consequences of market orientation (i.e. to explain when they consider the SPC to be successful in terms of members’ satisfaction, obtaining better income, and other objectives such as satisfying customers’ need), after which they expressed their opinions.

Pilot interviews were carried out with seven respondents (three experts, two SPC leaders, and two member farmers) to check the ease with which respondents responded and to check the appropriateness of the interview guide. For actual data collection, field assistants were recruited to facilitate effective communication between the researcher and the respondents (i.e. translation to/from local languages). Each interview question was translated in such a way that interviewees could easily understand and respond. Overall, we obtained a purposive sample in which in-depth interviews were conducted with a total of 44 respondents: 16 SPCs leaders, 12 member farmers, and 16 experts. Experts included those who have in-depth knowledge and experience on the SPCs regarding their organization, seed production, and marketing activities. Experts include those who have relevant educational backgrounds and experience in research, seed projects, NGOs, and government offices either in marketing, cooperative marketing or agribusiness, economics, or seed development and extension. During interviews, a digital voice recorder was used to gather all the information and to increase the accuracy of data presentation.

Data analysis

The data collected were analyzed using full transcripts of the individual interviews. We used Atlas.ti software to analyze the transcribed data. A total of 44 documents were uploaded into the software. Data were classified along the two main parts of the interview: market orientation understanding and market orientation practices, differentiating between the three groups of respondents. For market orientation practices we further differentiated the data among the three components of market orientation: information generation, information dissemination, and responsiveness.

Upon careful reading of all transcripts, an inductive data analysis was used for coding, categorizing, and identifying the key themes (Lincoln and Guba, 1986 ). This was a ‘bottom-up’ approach, progressing from a very detailed level to greater generality by assigning text fragments without prior assumptions. Inductive data analysis refers to approaches that primarily use detailed readings of raw data to derive concepts, themes, and/or models through interpretations made from the raw data by an evaluator or researcher (David, 2006 ). We analyzed our data as they became available to check and refine emerging understandings. Line-by-line coding was applied to interview transcripts. We identified representative primary codes (quotations of the respondents with similar meanings) from text fragments that were related to the market orientation understanding and market orientation practices. We further added codes and then finally condensed codes (family codes) to those that can capture critical aspects of the market orientation practices.

The concept of market orientation

The concept of market orientation understanding was expressed as a mix of more conceptual (“when do you consider your (/an SPC) to be market-oriented?”) and behavioral (“what activities does your (/should an SPC) do to be market-oriented?” ) quotations which are combined in the analysis.

From the primary codes that we extracted from the interview transcripts, a clear pattern emerged in terms of twelve key topics (elements) of market orientation, which could further be classified into five major themes (see Table 1 ). These major themes of market orientation are described below in detail.

Quality of produce emerged as the dominant theme from the interviews. In a sense, seed quality refers to having the necessary elements of the seeds that customers want including good germination and moisture content, free from unwanted seed and inert materials, and high market value. Buyers require quality seeds to increase yields and obtain high incomes. It was expressed in a more/narrow product quality sense as the supply of quality product and in the value/economic sense as the supply of high market value products . At the level of individual quotes, quality of the produce was referred to as ‘focus on seed quality’, ‘provision of quality seed to the market’, ‘production of market demanded seed’, ‘production of improved seed’, ‘sufficient quality seed production’, ‘supply of quality seed for customers’, ‘timely provision of quality seed’, ‘work on providing quality seed production’, etc. Respondents stated:

“If we use all the required agricultural inputs and produce quality seed, I can say our cooperative is market-oriented.” (farmer11)

“Customers do not have any complaint on the seed that we delivered. In general, we are providing quality seed for our customers.” (farmer2)

Value-adding activities emerged as a second important theme in relation to the market orientation of SPCs. It was expressed in terms of internal activities such as seed value addition , external activities of the SPC in terms of selling the seed directly to customers and developing better market strategies , as well as the outcome level in terms of profitability . Profitability was emphasized as most respondents believe that profit is the key for the consistent growth of the business. Practitioners explained:

“… a cooperative is market oriented when it produces quality seed and sells its seed with reasonable profit.” (leader2)

“… a seed producer cooperative can produce improved quality seed and become profitable. It also obtains high income….. because of this its members and other farmers in the community can benefit from producing improved seed …” (farmer1)

In addition, several respondents expressed value-adding activities in terms of quotes related to ‘provide the seed with reasonable profit’, ‘sell the seed with profit’, and ‘when using value additions profitably’. Experts particularly linked the high profitability with the value-addition capabilities of the SPCs. For example, one expert said:

“I can say a given cooperative is market-oriented when the seed (it produces) is cleaned and sold directly to its customers by its own capacity…. it can obtain higher prices and become profitable by packaging its own seed.” (expert2)

External orientation came out as a third key theme of market orientation in SPCs and basically relates to the concept of information-based competitive advantage in the market place. External orientation covers the topics of access to market information , customer focus, and competitor orientation . Results show that most SPCs are more customer-focused rather than competitor-oriented. Several respondents shared the opinion that the SPCs should try to satisfy their customers and should be customer-oriented. It was mentioned by the respondents that customers are satisfied when they get what they want, which in turn will turn them into loyal customers. For example:

“… for SPC to be market oriented first it should collect information about the benefit of seed production and marketing. Then, it should produce seed that customer farmers need…. able to process and pack accordingly. If SPC is in a position to do all these activities, I can say the cooperative is market-oriented.” (expert4)

“… Furthermore, from a marketing point of view the cooperative should know in advance who really demands its seed, when they need the seed, which quality standards, and the amount of the seed they want to buy …” (expert5)

“In addition, I can say a cooperative is market-oriented when it is able to process and pack its seed by itself and satisfy its customers. Customers can only be satisfied when we deliver quality seed …” (leader4).

Business organization came out as a relevant theme, although less frequently articulated than the previous themes. It relates to the performance of the SPC in terms of it being a well-organized and managed cooperative with committed and capable members who are professionally disciplined to supply quality seed. Most respondents emphasized that SPCs should be well organized and their members should be committed to becoming profitable and stay in the business. For example:

“Our cooperative is working hard to produce and maintain quality seed …” (leader9)

“We have our own bylaws to maintain the seed quality.” (farmer12)

At the more specific level of quotes, the business organization was expressed in such terms as ‘strong relationship with partners (i.e. supporting organizations)’, ‘when SPCs are able to obtain support from partners’, ‘when SPCs are able to develop a plan for quality seed production and marketing’. Moreover, respondents explained the commitment in terms of high member participation, and members’ integrity and hard work.

Supplier access is the final theme that emerged from the interviews, reflecting the important task of cooperatives to ensure access to inputs and services for their members to enable them to produce the required quality and quantity of seed. Cooperatives are supporting their members to access the necessary inputs and services at the right time and at the desired level, which was expressed by respondents as inputs and services access for members . The argument centers on access to basic seed. Because of the high basic seed shortage in the country, the SPCs usually approach partners (agriculture office, cooperative promotion office, research institutes, public seed enterprises, seed-related projects, etc.) to get support to access basic seed from available sources. Respondents explained:

“In general, SPCs should access quality basic seed from seed sources and distribute it to their members.” (expert10)

“We accessed basic seed from seed sources through the support of district offices of agriculture and cooperative promotion.” (leader5)

Experts’ vs. practitioners’ interpretation of market orientation

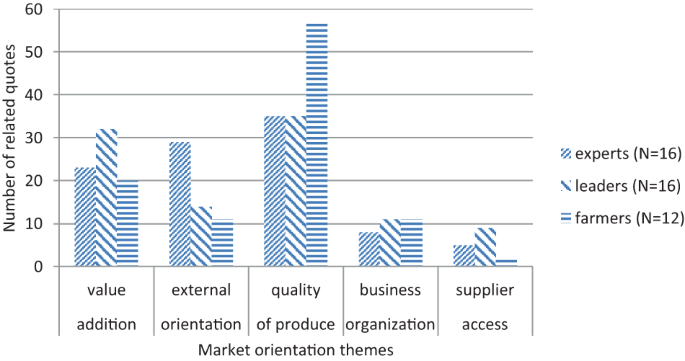

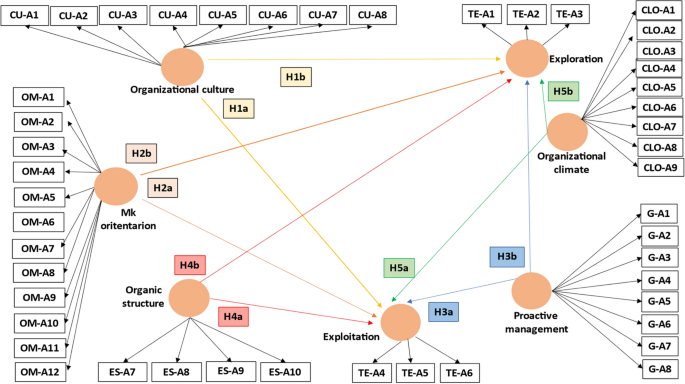

Figure 1 shows the occurrence of quotes related to the five themes of market orientation in the context of Ethiopian SPCs as obtained from three respondent categories. From the occurrence of quotes (relative number of quotes within each of the five themes), several similarities and differences stand out. First of all, the quality of produce is seen as the dominant element of market orientation for all respondent groups but is particularly prominent in the perception of farmers/members. Experts emphasize external orientation as a crucial element of the market orientation concept much stronger than the SPC leaders and member farmers. SPC’s value-adding activities are perceived by all respondent groups as an important component of market orientation, but more so by SPC leaders than by member farmers and experts. All groups see business organization as a component of market orientation without too much distinction between respondent groups. Access to seed is seen as a less central element of market orientation, although more prominent by leaders than by experts and particularly farmers.

Response pattern of experts, leaders and farmer members on market orientation themes.

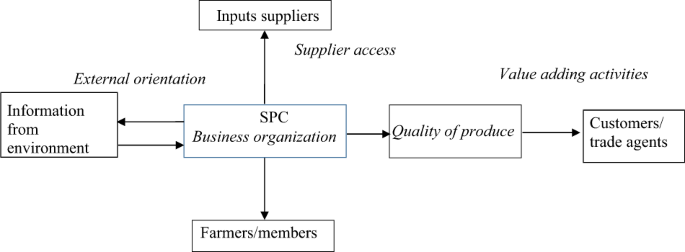

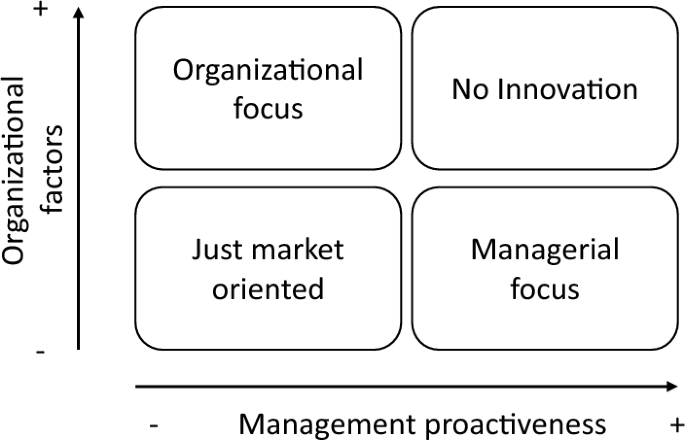

Overall, when reflecting on market orientation as a general concept in the context of SPCs, experts, and practitioners do agree on five key themes, although they do emphasize specific themes to different degrees. We developed the conceptual model shown in Fig. 2 on the basis of this qualitative research. Business organization leads to better access to inputs from potential suppliers. Inputs may include seeds, fertilizers, and agrochemicals, but centrally focuses on accessing basic seed from certified suppliers such as research centers, universities, and big seed companies. Sometimes SPCs’ access to basic seed depends on the business-to-business relationship with suppliers. Well-organized SPCs have strong relationships with suppliers, which results in accessing the right input at the right time. The business organization also contributes to better-coordinating members of the cooperatives. SPCs search for and provide the necessary inputs to their members to satisfy their basic seed demand and help them to produce the best quality seed that customers need. The quality of seed can influence buyers to pay higher prices and contribute to a higher market share. The business organization also links with gathering relevant information from the environment in terms of customers’ needs and competitors´ actions. It also depends on the organizational capacity of the cooperative to disseminate the information gathered to members and respond accordingly. Business organization also leads to more customer satisfaction by adding value to the product. Value addition in the seed business may include sorting, grading, transporting, and packaging.

Conceptual model of market orientation in SPCs.

Specific market orientation practices

Information generation, information dissemination, and coordinated responsiveness to that information are core behaviors within market orientation theory. In the second part of the interviews, these behaviors were assessed and made explicit by respondents as they apply to their specific context, again in terms of “what is being done” (practitioners) and “what should be done” (experts). In this section, we discuss these specific market orientation behaviors in terms of information generation, information dissemination, and responsiveness.

Information generation

Information generation about the seed that the SPC is producing and/or wants to produce came out as a major theme, together with information on market prices, customers’ needs, and to a lesser degree information about competitors. Experts consider information on seeds that have high market value important, which is also dominant in the current practices of SPCs. Two experts stated that:

“In the first place they (SPCs) should gather information about the varieties demanded by the market, and the place where these varieties can be sold.” (expert4)

“When we say collecting market information, it includes information about whether the crop/seed aligns with market demand. Before they start seed production, they have to know which crops/varieties are really demanded by the market.” (expert13)

Information that SPCs are gathering about products (seed) includes the seed demand (quality and variety) by customers, the adaptability of the seed to the locality, the seed productivity (production potential), availability of alternative varieties, and the place to market the seed. They gather market price information from local markets and markets outside their vicinity.

“We access market information from partners about which crops/varieties we need to produce to profit, and how to sell our product (seed) for a reasonable price.” (leader2)

Experts also emphasized the importance of collecting information about customers as a basis for SPCs to design appropriate strategies and to find all possible ways to satisfy their customers and obtain a better income.

“… They should also collect information about customers’ needs and how they can satisfy their needs …” (expert16)

Collecting market information about customers is, however, not very much considered in the current practices of SPCs. The emphasis in information gathering is on prices. The market price information is useful to set the seed price while considering customers’ willingness to pay. SPCs also access information about their competitors through external contacts. Some respondents consider big government seed enterprises as their competitors, but most consider them as partners. In some cases, respondents consider other SPCs as their competitors. For example:

“We also gather information about other seed producer cooperatives, and we understand where we stand as compared to other cooperatives …” (leader5)

Both experts and SPC leaders/farmers emphasize partners in the network as important sources through which information can be obtained. Experts suggest that SPCs should collect and access information through external contacts such as district offices, research institutes, seed-related projects, Universities, NGOs, and cooperative Unions. Experts’ suggestions take into account that most of the existing SPCs have limited technical and financial capabilities to gather market information by themselves, and do not have their own employees responsible for gathering market information. One expert said:

“There are stakeholders supporting the seed producer cooperatives. For example, … in connection with marketing and market linkage SPCs should gather information from district office of marketing and cooperative promotion. In addition, SPCs should access information from other organizations including NGOs …” (expert5)

This is also reflected in current SPC practices, where respondents stated that SPCs are gathering information from partners and intermediaries (e.g., big seed enterprises). Particularly local-level government offices, which are closely working with SPCs, are supporting the cooperatives in information gathering. One SPC leader explained:

“Our cooperative is gathering information from the district office of cooperative promotion, district office of agriculture, the ISSD project and seed enterprises.” (leader1)

Experts suggested that SPCs should not only rely on information from partners and intermediaries but also collect such information themselves. However, this is not a well-developed practice in SPCs yet.

In line with market orientation theory, experts indicated that customers, particularly farmers in the direct vicinity can be an important source of information to SPCs, but this practice is implemented only to a limited degree in SPCs. An expert from the district office of cooperative promotion and marketing suggested:

“Information should be gathered from experts, the market place (traders), and customers. I said from customers, that is, from customer farmers. They should ask customer farmers to give feedback about their seed … they should gather information about customers’ preference from farmers themselves.” (expert6)

In agreement with market orientation theory, competitor intelligence came up as a theme among experts (“should be done”), but also this theme seems weakly developed in current SPC practices. Competitors in a sense may include other SPCs within and outside their locality, as well as private and government seed companies. Experts explained:

“I think SPCs should also collect information from other seed producer cooperatives…” (expert5)

“…furthermore, SPCs should know their competitors’ price and competitors’ product. They should know where their competitors are found … are they near to their place or far away? Do competitors have transportation facilities and road access?” (expert12)

In terms of how SPCs should collect market information, experts suggested that SPCs should gather market information through both formal and informal mechanisms. Formal information-gathering mechanisms include collecting market information by asking and interviewing partners, reviewing documents, and through structured information-gathering techniques. Experts also acknowledged the importance of various informal ways of collecting market information through personal contacts and communication. Experts suggested SPCs should use the various social gatherings to collect market information from customers and other supporting organizations.

“SPCs should also gather market information from the community … when people gather for various activities-for instance in Church …” (expert1)

In fact, SPCs are gathering information (e.g., on market prices) when collecting/purchasing the seeds from their members and when they are selling to customers. Members also gather price information from the market place when they go there for their own purposes, as well as from neighbors, friends, and relatives. Accordingly, members inform cooperative leaders about the price information they come across. SPCs also exchange market information with each other.

“We collect information from farmers in neighboring villages …” (leader14)

“We also ask market information from office of marketing and cooperative promotion.” (leader8)

“There are other SPCs in other areas of the region… we ask them through telephone about the market price of the seed in their respective areas.” (leader9)

Experts see an important role for SPC committees in gathering market information and a role for the SPC chairman. Depending on the existing situation of a given SPC, the committee responsible for gathering market information would be either a marketing committee, selling committee, or executive committee. Experts suggested that the executive committee members should be responsible for collecting the market information because in most cases they have a better education, more experience, and more social status than other SPC members. A few suggested that the chairman of the cooperative should be responsible. Some others also suggested that SPCs should have employees responsible for both gathering market information and supporting the SPCs in other technical activities. Experts explained:

“In my opinion, the capacity of the cooperative determines who should be responsible to gather market information. If the cooperative has financial capacity, it can hire a professional/expert … if it is not able to hire an expert, the leaders of the cooperative should be responsible to gather market information.” (expert2)

“From my experience, the chairman of the cooperative should be responsible for gathering market information.” (expert16)

SPCs have various committees with specific responsibilities. Several interviewees stated that these committees are gathering market information. Some respondents said that information is gathered by the chairman of the cooperative, indicating the chairman is fully responsible for information generation. Although different committees are involved in gathering market information depending on the organizational structure of the SPCs, most interviewees believed that it should be the responsibility of the executive committee.

“Market information is gathered by various committees of the cooperative.” (leader5)

“We made the chairman responsible. Thus, he has to gather information about the market.” (farmer3)

Information dissemination

Information dissemination is a common practice within the SPC, as indicated by SPC leaders/farmers. They share and discuss market information within the business, particularly about market prices, market places, expected profit, quality of product, and customers’ preferences as suggested by experts. However, different from what experts envisioned, this sharing focuses on customer needs and not on competitor information. Both the committees and the chairman take a leading role in this information dissemination. One farmer said:

“We, members, usually discuss where, how and for how much to sell our seed to buyers.” (farmer2)

Market information should be shared and discussed within the SPC, according to experts. They suggested that information about market prices, market places, expected profit, quality of products, customers’ preferences, and competitors should be shared and discussed within the SPC. In the SPCs’ context, members of the cooperatives are owners of the business and therefore information should be shared among members.

Both experts and SPC leaders/farmers acknowledge the importance of formal and informal ways of information dissemination. According to experts, information should be disseminated during the general assembly facilitated by the executive committee and assemblies of other sub-committees. Sharing information at local and religious festivals and through contacts within their neighborhood are recommended channels for information dissemination. In most cases, SPCs use informal events, for example, social gatherings, religious places, and community-based organizations. The internal hierarchical structure of the cooperative also helps to disseminate information from committees to members, and between committees. The chairperson of the SPC and other committees disseminate the information to all members through internal mechanisms which may vary among SPCs depending on specific social, cultural, and religious practices.

“One of the mechanisms of information dissemination within SPC is through the general assembly….” (expert3)

“Executive committee members discuss the market information…. and then this information is further disseminated to and discussed with members. We know that there will be a problem, if we do not discuss the market information with members.” (leader8)

“We also share information during informal meetings in the Church. We use local community-based organizations to share market information.” (farmer3)

Concerning the responsibility for information dissemination, leaders and members believed that cooperative leaders should take responsibility. However, a few of them preferred the chairperson to be responsible mainly because of individual commitment and capabilities. Some respondents described that all members are equally responsible for disseminating information. One farmer explained:

“… we shouldn’t keep silent by saying it is only the responsibility of the executive committee. We should support the executive committee …” (farmer7)

Responsiveness

Responsiveness to market information about customers’ preferences by setting seed prices, providing the right quality seed in sufficient quantities, and adding value to the seed is suggested by experts. Experts particularly advised SPCs to respond based on seed pricing mechanisms considering production costs, a profit margin, and whether the seed quality meets the needs of customers and competitors’ seed prices.

“In relation to their competitors, SPCs should understand what their competitors are doing at present. Accordingly, they should respond to the market information by considering the pricing mechanism of the competitors.” (expert1)

Experts agreed that SPCs should be responsive to market knowledge by providing quality seed and by considering the specific needs of their customers. SPCs should not produce seeds with low market demand and seeds that can be easily produced by other farmers. They should adapt themselves to produce more than one crop (and variety) and satisfy their customers’ preferences by widening their product portfolios i.e. product diversification. They also stated that SPCs should focus on providing seed that receives limited attention and interest from public and private seed companies. Locally demanded crops and varieties are often ignored by large seed companies because the demand and profit margin are too small for these companies to justify their investment. This provides a good opportunity for SPCs to satisfy specific target customers’ demands and eventually obtain better profit. Moreover, experts suggested more value additions to the product in relation to market responsiveness. Almost all experts stressed that SPCs should be responsive to customers’ preferences. To achieve that, the SPCs should know what their target customers really want to have and understand the places where their buyers want to obtain their seeds.

“I think the key thing that is expected from the SPCs is to provide the product in accordance with the interest of customers.” (expert11)

“It would be better if the SPCs had its own branches and shops to distribute their seed to buyers.” (expert2)

SPC leaders/farmers said that the SPCs are making efforts to respond to the market by supplying quality seed and fixing the price by considering their production cost and profit. However, current SPC practices to add value to the seed are limited. When SPCs sell their seed without further processing and packaging, it limits their profit and their future competitive capabilities. Particularly the SPCs producing seed in contractual agreements with big seed enterprises sell their seed with limited value addition.

“Currently, we are providing quality seed to our customers based on an agreement. Because of limited capabilities, we are not able to reach a position to provide quality seed using post-harvest technologies such as treating, processing and packaging.” (leader1)

On the other hand, those SPCs selling their seed directly to farmer customers have more experience in value additions including through seed processing and packaging. Farmers said:

“We are distributing our seed with different packaging size. For instance, we distribute with 15 kg and 100 kg bags.” (leader6)

“We usually process and pack our seed before selling.” (farmer5)

SPCs also respond to the market by providing alternative crops/varieties. When SPCs understand that a given crop/variety is not profitable, they change the variety based on market interest, which is indicative for their adaptation strategy. Moreover, SPCs encourage their members to provide large quantities of quality seed to the cooperative. It is observed that some SPCs award prizes for members who provide the largest quantities of quality seed. Farmers that provide higher quantities of seed receive higher dividends and thus have a better income than other members.

In the Ethiopian SPCs context, we have compiled a number of context-specific market orientation practices. The five market orientation themes (quality of produce, value addition activities, business organization, external orientation, and supplier access) can be related to the “prototypical” market orientation model. The themes of external orientation and supplier access capture the orientation on developments and constraints in the environment. Through their external networks, SPCs gather market information from the external environment including mainly from customers (buyers), trade agents, partners, intermediaries, and in very rare cases from competitors. As a unique case for SPCs, they work with the external environment to access the required inputs and services, and more specifically to get access to basic seed. SPCs usually approach research centers, universities, seed companies, and other partners to access the basic seed. Business organization relates to what is recognized as antecedents of market orientation such as top management characteristics, organizational structures, and interdepartmental dynamics (Jaworski and Kohli, 1993 ). Like other businesses, better organizational capabilities of SPCs matter a lot in successful business venture. Value-adding activities of the SPC , represent a consequence of market orientation which relates directly to the performance of the business in terms of customer satisfaction, profit (financial performance), and employees’ satisfaction. In the case of SPCs, members’ satisfaction can be also considered (Opoku et al., 2014 ). Higher quality of members’ produce plays a mediating role between market orientation and consequences. The effect of quality of produce reflects itself in higher price and higher market share. Our study is in alignment with literature that captures a broader concept of market orientation related to the capabilities of market-driven organizations, which makes less distinctions between the concept of market orientation, its antecedents, and consequences (Li et al., 2018 ). Our results suggest that indeed the concept of market orientation has equal recognition in the D&E context.

Our results deviate from the predominant view about the importance of competitor orientation. SPCs largely emphasize customer satisfaction with less focus on competitor orientation. Experts emphasize external orientation more strongly than SPCs currently do. Farmers emphasize the consequence of market orientation for their performance (quality of produce) and SPC leaders seem to put relatively more emphasis on the value-adding activities and supplier access. This is reflective of the different roles that experts, SPC leaders, and farmer members hold in the complex supply chains that characterize D&E markets. However, the different components of the market orientation model in marketing theory seem to be well captured. Importantly, as cooperatives, SPCs serve two customer groups both buyers (farmers, unions, traders, and big seed companies) and member farmers.

The present study identified supplier access as an important factor in the conceptualization of market orientation, next to customer and competitor orientation and inter-functional coordination. This finding reflects that in complex and fragmented value chains in D&E countries and particularly in the context of seed production, free access to high-quality inputs cannot be taken for granted. Rather it needs to be carefully managed through sensing and responding activities. Supplier orientation can be recognized as a key component of market orientation within a value chain context. Our results suggest that in D&E context supplier orientation may be an important part of the market orientation concept.

The specific market orientation behaviors of information generation, dissemination, and responsiveness are well recognized also in a D&E context. Both experts and SPC members emphasize the importance of generating information about the quality of inputs (basic seed as input to produce commercial seed). Moreover, SPC members emphasize a focus on information about the market value of the produce (in terms of price and profit), more so than experts think they should. On the other hand, whereas experts emphasize the importance of collecting competitor information, this is not practiced by most SPCs. The latter finding relates well to other research on market orientation in D&E countries and Ethiopia in particular (e.g., Ingenbleek et al., 2013 ). The concept of competitor orientation does not resonate well in cultures with high levels of embeddedness and a focus on social capital, which is typical for D&E economies (Steenkamp, 2005 ). Together these findings suggest that in a D&E context competitor orientation may not be a central component of the market orientation concept.