SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

The impact of boarding school on student development in primary and secondary schools: a meta-analysis.

- School of Education, Minzu University of China, Beijing, China

As a long-established model of schooling, the boarding system is commonly practiced in countries around the world. Numerous scholars have conducted a great deal of research on the relationship between the boarding school and student development, but the results of the research are quite divergent. In order to clarify the real effects of boarding school on students’ development, this study used meta-analysis to quantify 49 (91 effect sizes) experimental or quasi-experimental studies on related topics at home and abroad. The results find that: (1) Overall, boarding school has no significant predictive effect on student development, with a combined effect size of 0.002 ( p > 0.05); (2) Specifically, boarding school has a significant positive predictive effect on students’ cognitive development ( g = 0.248, p < 0.001), a significant negative predictive effect on students’ affective and attitudinal development ( g = −0.159, p < 0.05), and no significant predictive effect on students’ behavioral development ( g = −0.115, p > 0.05) and physical development ( g = −0.038, p > 0.05); (3) The relationship between the two is moderated by the school stage and the type of boarding school, but not by the instruments; (4) Compared with primary school students, senior high school students and urban boarding students, the negative predictive effect of boarding system on junior middle school students and rural boarding students is more significant. In addition, there are some limitations in the study, such as the limited number of moderator variables included, the results of the study are easily affected by the quality of the included literature, and the dimensionality of the core variable “student development” is not comprehensive enough. In the future, further validation should be conducted through in-depth longitudinal or experimental studies.

Introduction

Boarding school, which began in British public schools, is a common form of schooling that provides students with accommodation and food, and integrates personal lives of students with their academic lives ( Dong, 2012 ). In boarding schools, a relatively closed school management model is generally adopted, and dormitories, canteens and other related living facilities are equipped to meet the basic living needs of students. The boarding school, as a mode of schooling, not only has a relatively long history in the West, but also has been practiced in China for nearly 40 years or so, covering all stages from kindergarten to university. There has been a great deal of academic research around boarding school, mainly including studies on the functions of boarding school ( White, 2004 ), the internal management problems of schools ( Zhang, 2006 ), the impact of boarding school on the physical and mental development of students ( Kahane, 1988 ), and the relationship between boarding school and families ( Ben-David and Erez-Darvish, 1997 ). With the increasing size of boarding school and the younger age of boarding students, boarding school has become an important and unique part of the school system. In recent years, research on the boarding school has gradually shifted from exploring the value implications to promoting students’ development, such as the impact of boarding on students’ academic performance ( Foliano et al., 2019 ) and the impact of boarding on students’ mental health ( Yang and Yan, 2022 ). However, these studies only discuss the relationship between boarding school and one aspect of student development. Indeed, student development encompasses multiple aspects of the educational process and developmental content ( Pan, 2019 ). At the same time, some studies have pointed out that although boarding school helps students accept multiculturalism, promote students’ socialization ( White, 2004 ) and enhance students’ academic performance ( Zhou and Xu, 2021 ), there are also some negative effects, such as affecting the formation of students’ personality ( Schaverien, 2010 ) causing social and emotional distress to students ( Kleinfeld and Bloom, 1977 ), and affecting physical development ( Xu et al., 2014 ). So, how does boarding actually affect the overall development of students? Are there differences in the role of different aspects of student development in a boarding environment? It is not only a summary of the effectiveness of the boarding school that has been implemented for a long time, but also an important question that needs to be answered urgently in order to promote the normalization and under-aging of boarding school.

The correlation between boarding school and the development of students

Many studies have centered on the impact of boarding school on student development at different school stages, types of boarding school and instruments. However, there are some differences in the findings of the studies, which are broadly divided into three categories.

The first view is that boarding school has a significant positive predictive effect on student development. On the one hand, boarding school increases and standardizes the study time of students by providing a collectivized learning and living environment ( Yao et al., 2018 ), which in turn improves students’ academic achievement ( Curto and Fryer, 2014 ; Behaghel et al., 2017 ; Foliano et al., 2019 ). At the same time, boarding school also reduces students’ undesirable behaviors, such as a decline in absenteeism ( Martin et al., 2014 ), and has a positive impact on students’ cognitive development. A survey by the American Association of Boarding Schools (2013) found that 68% of boarding school students believed that boarding school had helped them improve self-discipline, maturity, independence, cooperative learning, and critical thinking. On the other hand, group home living increases contact between students and promotes emotional communication and companionship among peers ( Martin et al., 2014 ; Bosmans and Kerns, 2015 ). This close peer relationship not only helps boarding students better adapt to school life ( Segal, 2013 ) and enhance their ability to live independently ( Ma, 2012 ), but also increases student satisfaction with school and life, and promotes the development of students’ healthy personality ( Wu et al., 2011 ). In addition, good peer relationships also serve as role models that can continuously stimulate students’ motivation and promote their interest in learning ( Kennedy, 2010 ). Multi-subject attachment theory suggests that the scope of the attachment relationship is not limited to the parent–child relationship, and that teachers, as one of the important attachment objects for boarding students, can to some extent “substitute for the parents” and “compensate” for the lack of parent–child relationship of boarding students ( Verschueren and Koomen, 2012 ). Supported by the theory of humanities and sociology and with the help of students’ autobiographies, White (2004) also amply substantiated the important role of boarding school in the development of students.

The second view is that boarding school has a significant negative predictive effect on student development. First of all, boarding school adopts a relatively closed management mode, which weakens the influence of the family and society in the growth of students, and causes certain harm to the physical and mental development of students ( Schaverien, 2010 ). Especially for younger students, they are more dependent on their families, so the role of family environment is more important for their socialization ( Yan et al., 2013 ). Secondly, boarding school is strictly regulated and competition within schools is fierce ( Yao et al., 2018 ). Coupled with the dilution of parent–child relationship, students lack effective emotional support ( Ye and Pan, 2007 ). As a result, boarding students are more likely to develop aversion to studying, leading to a decline in academic performance ( Lu and Du, 2010 ), which in turn leads to undesirable behaviors, such as truancy, school bullying and dropping out of school ( Pfeiffer and Pinquart, 2014 ; Shi and Zhao, 2016 ). Finally, the boarding environment increases the density of interactions between students, which tends to produce the contagion of negative emotions among peers ( Li and Lin, 2019 ). It usually manifests itself in the form of interpersonal hypersensitivity, accompanied by depression, anxiety, paranoia and various other negative emotions and psychological problems ( Niknami et al., 2011 ; Mander et al., 2014 ).

The third view is that boarding does not show significant differences in learning goals, learning engagement and mental health of students ( Li, 2007 ; Martin et al., 2014 ). On the one hand, although boarding students have more psychological problems at the time of admission, as they move up the grades, they become more resilient to school life and their psychological problems gradually decrease ( Liu et al., 2004 ; Xiao et al., 2010 ). On the other hand, boarding students can only communicate with their parents by phone as well as at home on weekends, which can not only dilute parent–child conflicts, but also satisfy students’ psychology of freedom and independence. Therefore, it is conducive to the development of parent–child relationship ( Shen, 2021 ). Additionally, the problem of parental attachment is mitigated due to the growing influence of teacher-student and peer relationships on students ( Wu et al., 2021 ).

Potential moderators of the association between boarding school and the development of students

Different school stages can affect the effectiveness of boarding school on student development. Most studies identify age characteristics as the main factor influencing students’ mental health ( Papworth, 2014 ; Wang and Mao, 2015 ). Primary school boarding students are young and have an imperfect level of physical and mental development. When primary school students are faced with an unfamiliar living environment, they often experience psychological maladaptation and difficulties in interpersonal interactions ( Wang, 2015 ). Due to their relatively complete physical and mental development, junior middle school boarding students have basically formed psychological qualities such as cooperation, self-discipline and freedom, and have a relatively favorable psychological environment. It further supports the negative effects of underage boarding on children’s emotions and socialization ( Wang, 2015 ). In addition, research is more divergent when it comes to academic development. Some scholars believed that there is no significant difference in the impact of boarding school on the academic performance of students in different grades ( Bozdoğan et al., 2014 ), and at the same time, boarding has the same degree of positive impact on students in all grades ( Gao, 2017 ). However, some scholars used instrumental variable regression to show that boarding has a more significant impact on the academic performance of primary school students, but not on junior middle school students ( Qiao and Di, 2014 ). Thus, the effect of boarding school on student development may be moderated by different school stages.

Different types of boarding school affect the effectiveness of boarding on student development. In general, boarding school can be categorized into rural boarding school and urban boarding school. Studies with rural boarding students concluded that boarding school has a positive impact on the academic performance of rural students ( Gao, 2017 ), which is consistent with the findings of numerous studies ( Du et al., 2010 ; Kennedy, 2010 ); but studies with urban boarding students found that urban boarding students have a significant advantage in academic performance ( Xu, 2019 ) and a better psychological condition than rural boarding students ( Luo, 2013 ). Compared to rural boarding students, urban boarding students have better access to social resources, boarding environment, faculty, and more advanced concept of family education ( Tan, 2020 ). In summary, there are some differences in the impact that different types of boarding school have on student development.

In terms of instruments, standardized scales, standardized tests, and self-administered questionnaires are widely used at present. Therefore, they can be divided into two categories: standardized and non-standardized instruments. The use of different instruments may affect the effectiveness of boarding on student development. For example, a self-administered questionnaire, the Mental Health Questionnaire for Junior Middle School Students, was used to measure the mental health level of students, and the results showed that the mental health of boarding students is significantly higher than that of non-boarding students ( Zhang, 2020 ); the results measured using the Diagnostic Test of Mental Health (MHT) is the opposite of the former, showing that the mental health of non-boarding students is significantly better than that of boarding students ( Chen, 2016 ). It follows that the effect of boarding school on student development may be moderated by the instruments.

Current study

In summary, the overall effect of boarding school on student development needs to be further tested. In addition, factors such as different school stages, types of boarding school, and instruments may moderate the relationship between boarding school and student development. Established research mainly discusses one aspect of student development and the findings are not consistent. Therefore, this study adopts the meta-analytical approach to integrate, evaluate and analyze the existing empirical studies on boarding school and student development in order to draw general and generalized conclusions.

Materials and methods

Data retrieval strategies.

This study utilized a variety of sources to collect literature related to the impact of boarding school on student development over the past three decades, both domestically and internationally. Specifically, firstly, the foreign language databases “Web of Science,” “Springer” and “Google Scholar” were searched with “boarding school,” “boarding” and “effect” and “impact” as the subject words, and a total of 1,325 foreign language documents were obtained. Secondly, in the Chinese databases of “CNKI,” “Wanfang Data” and “VIP “, a total of 1,524 Chinese literature was obtained by searching “boarding” and “boarding school” as the titles. The date of the search was 21 October 2023.

Inclusion criteria

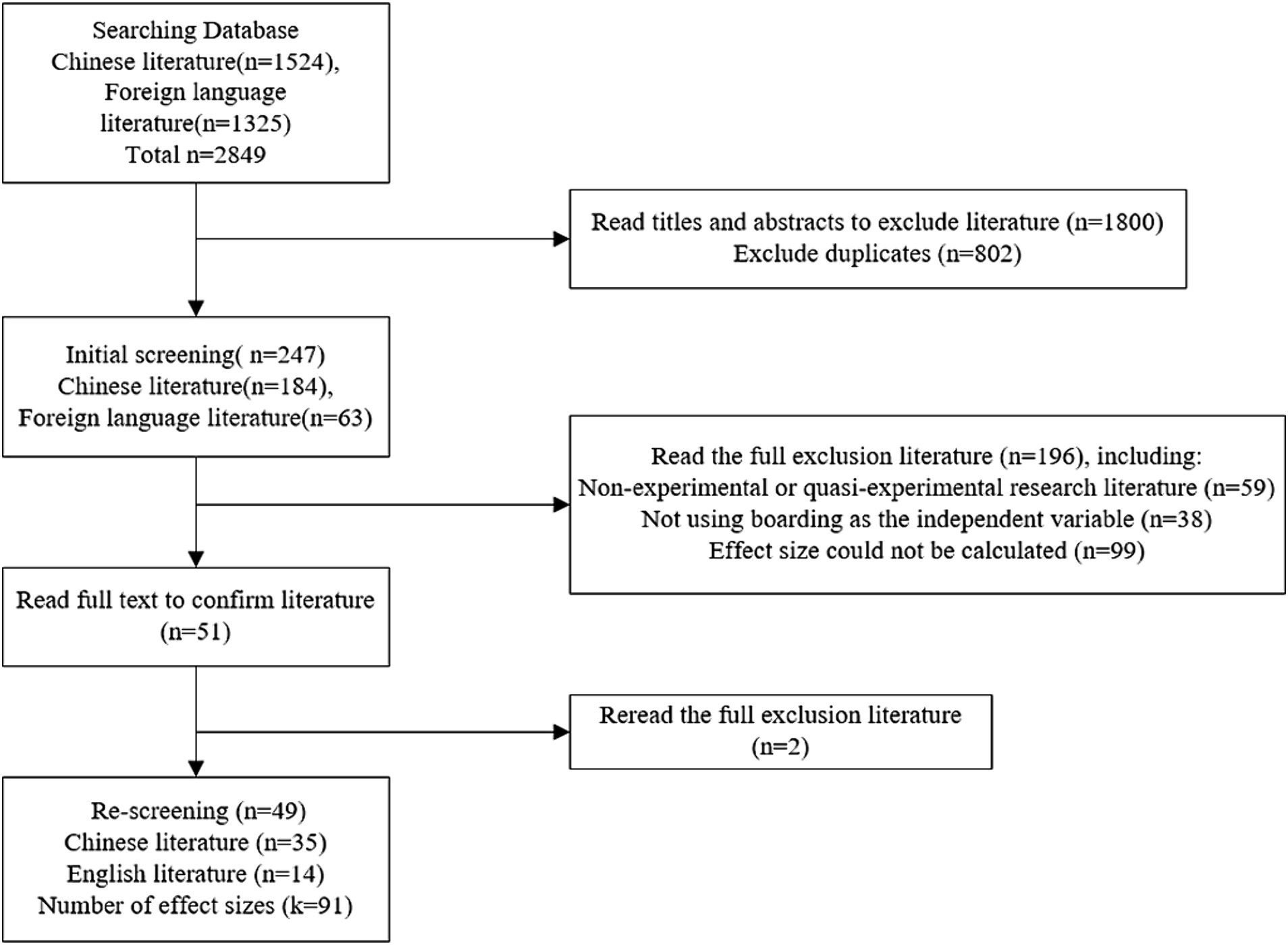

In this study, the Endnote20 literature management tool was used to screen the included literature according to the following criteria: (a) The topic of the study was the effect of boarding on students’ development; (b) The research subjects were primary and secondary school students; (c) The study needs to take boarding school as the independent variable; (d) The type of the study is an experiment or quasi-experiment comparing the differences in the development of boarding and non-boarding students, in which a single group of experiments need to provide pre- and post-tests data; (e) The study provides complete data that can calculate the effect size, such as the sample size (N), the mean (Means), the standard deviation (SD), or the p -value, t-value, and the correlation coefficient (r), and so forth; (f) Identical studies that had been published in a different format are excluded. After several rounds of literature screening and elimination of literature that did not meet the criteria, 49 papers were finally included and a total of 91 effect sizes were generated that could be used for meta-analysis. Among them, there were 35 articles in Chinese and 14 articles in foreign languages. The literature span from 1986 to 2023, but it was primarily focused on the last decade ( Figure 1 ).

Figure 1 . Flowchart of the inclusion protocol.

Coding procedure

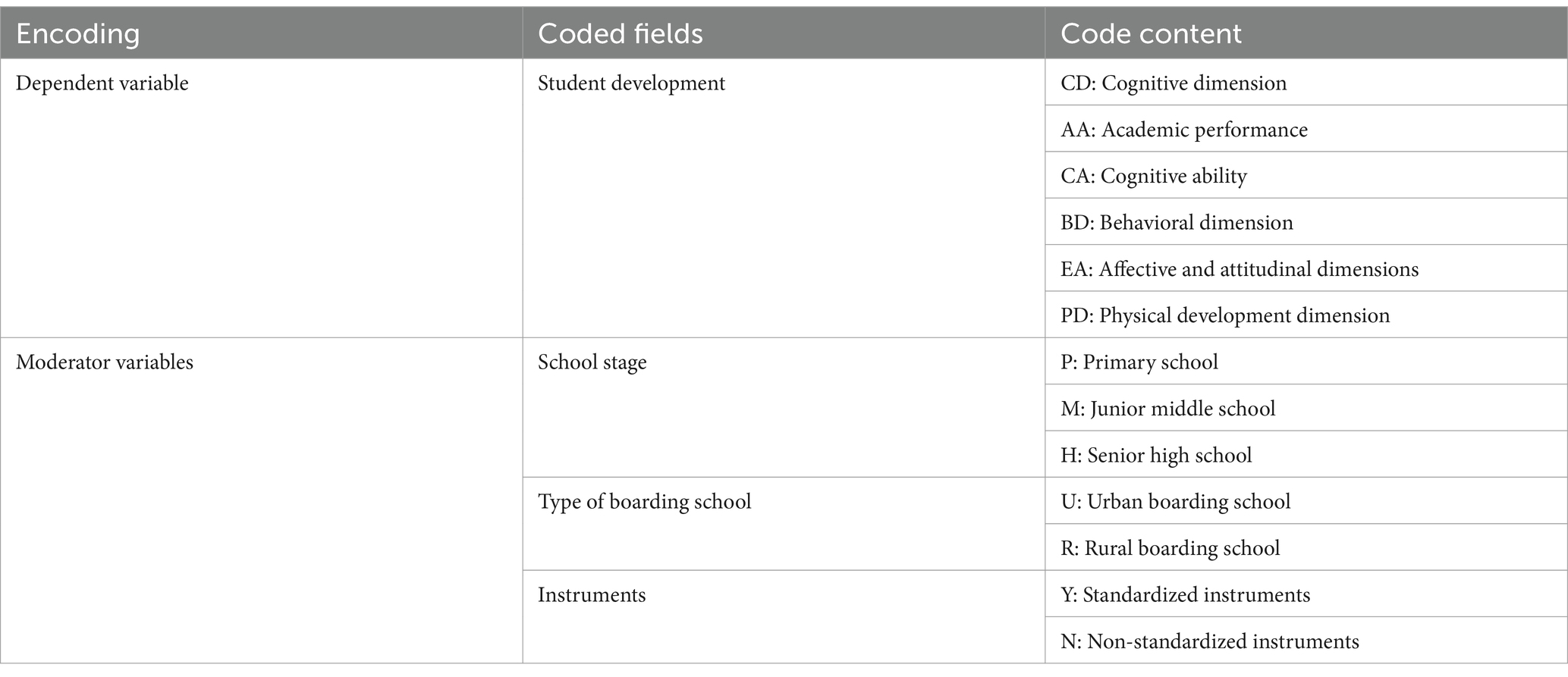

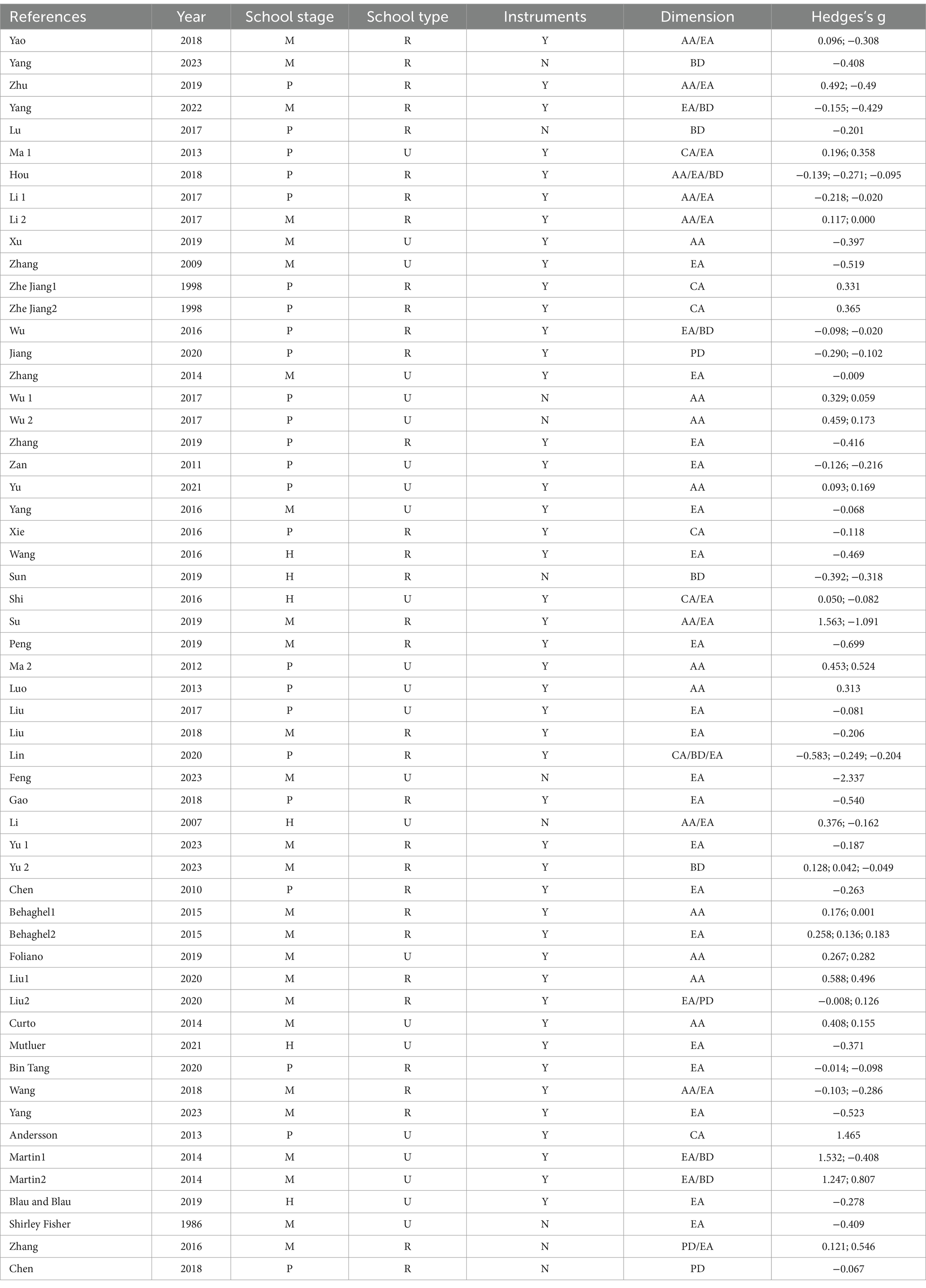

To further explore and analyze the impact of boarding school on students’ development, the key information was extracted and features coded from the included literature. In this study, 49 articles were independently coded by two coders to ensure reliability and consistency of the coding. There are three main aspects of coding:

The first is the basic information aspect of the literature, including the names of the authors, the time of publication, and data about the effect sizes.

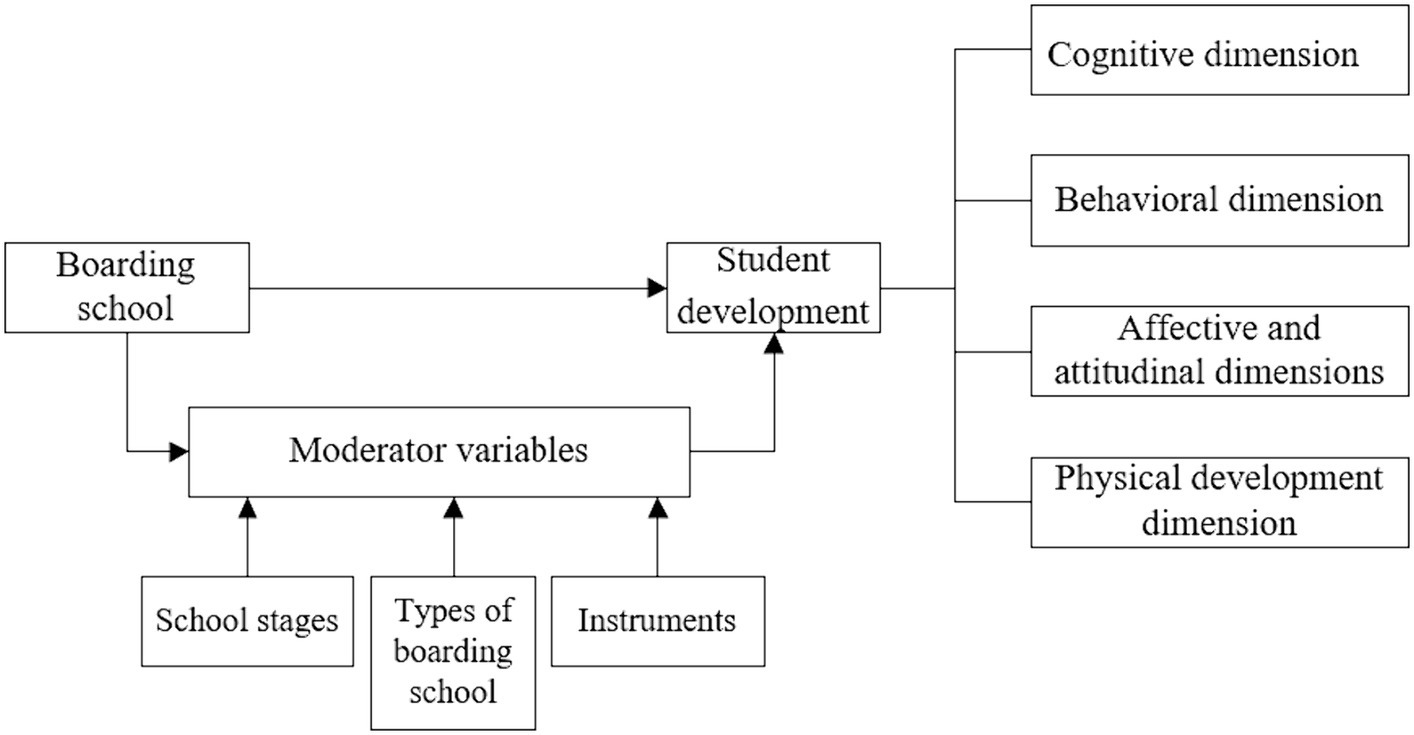

Secondly, in terms of the dependent variable, this study used student development as the dependent variable. According to Benjamin Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives ( Anderson, 2009 ), student development is categorized into three dimensions: cognition, behavior, and affect and attitude. In addition, the dimension of physical development has been added in line with the boarding schools’ provision of food and accommodation. Among them, the cognitive dimension mainly consists of students’ academic performance and cognitive ability. Academic performance is a sufficient but not necessary condition for the cognitive development, thus a distinction is made here between academic performance and cognitive ability. The behavioral dimension includes both pro-social behaviors, etc., as well as problematic behaviors such as school bullying and absenteeism. The affective and attitudinal dimension includes students’ emotions, self-esteem, and motivation, etc. The physical development dimension includes the student’s BMI, nutrition, etc.

The third is the moderator variables, including three variables: school stage, the type of boarding school and instruments. First of all, the development of students is stage-specific and sequential, and the impact of choosing boarding at different school stages is also different, mainly including three stages: primary school, junior middle school and senior high school. Secondly, boarding schools can be divided into different types according to different classification criteria. In order to harmonize the definition of boarding school in domestic and foreign studies, this study mainly categorized boarding school into urban boarding school and rural boarding school according to geography. Finally, according to the degree of standardization of the instruments, they are divided into standardized and non-standardized instruments, where standardized instruments refer to the use of standardized questionnaires, scales, etc. to measure student development.

The included literature were coded according to the above characteristics, including author information, year of publication, dependent variable dimensions, school stages, school types, instruments, and effect size. The effect sizes d reported in the collected literature were transformed by the following equation: g = d [1−(3/(4 df−1)), df = n 1 + n 2 -2. If the included studies did not report an effect size d, they were calculated from raw data such as sample size, mean, and standard deviation: d = (M1–M2)/Spooled, Spooled = [(n 1 –1) s 1 2 + (n 2 –1) s 2 2 /n1 + n 2 -2] 1/2 . In addition, if the included studies did not fully report raw data such as sample size, mean, standard deviation, etc., they were transformed by the χ 2 value, F value or t value of the raw data: d = 2[ χ 2 /(N− χ 2 ) 1/2 ; d = 2/F (n 1 + n 2 )/n 1 n 2 ] 1/2; d = t /(n 1 + n 2 /n 1 n 2 ) 1/2 .

Effect size

Due to the small sample size of this study, Hedges’ g -value was selected to measure the impact of boarding school on students’ development. According to Cohen’s criterion for judging the effect size: when the effect size is less than 0.2, its influence is small; when the effect size is more than 0.2 and less than 0.5, there is a moderate influence; when the effect size is more than 0.8, it has a large influence ( Figure 2 ).

Figure 2 . Meta-analytic framework diagram.

Statistical analysis

The concept of meta-analysis was pioneered by Glass, an American psychologist. Meta-analysis, which aims to synthesize existing research, is a research process and systematic method for quantitatively combining and analyzing the effects of multiple conflicting studies on a given topic ( Glass, 1976 ). In this study, the meta-analysis software Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Version 3.0 was used for data processing and analysis, and relevant data from the literature, such as the values of sample size, standard deviation, and mean, were entered into CMA for relevant calculations.

Publication bias analysis

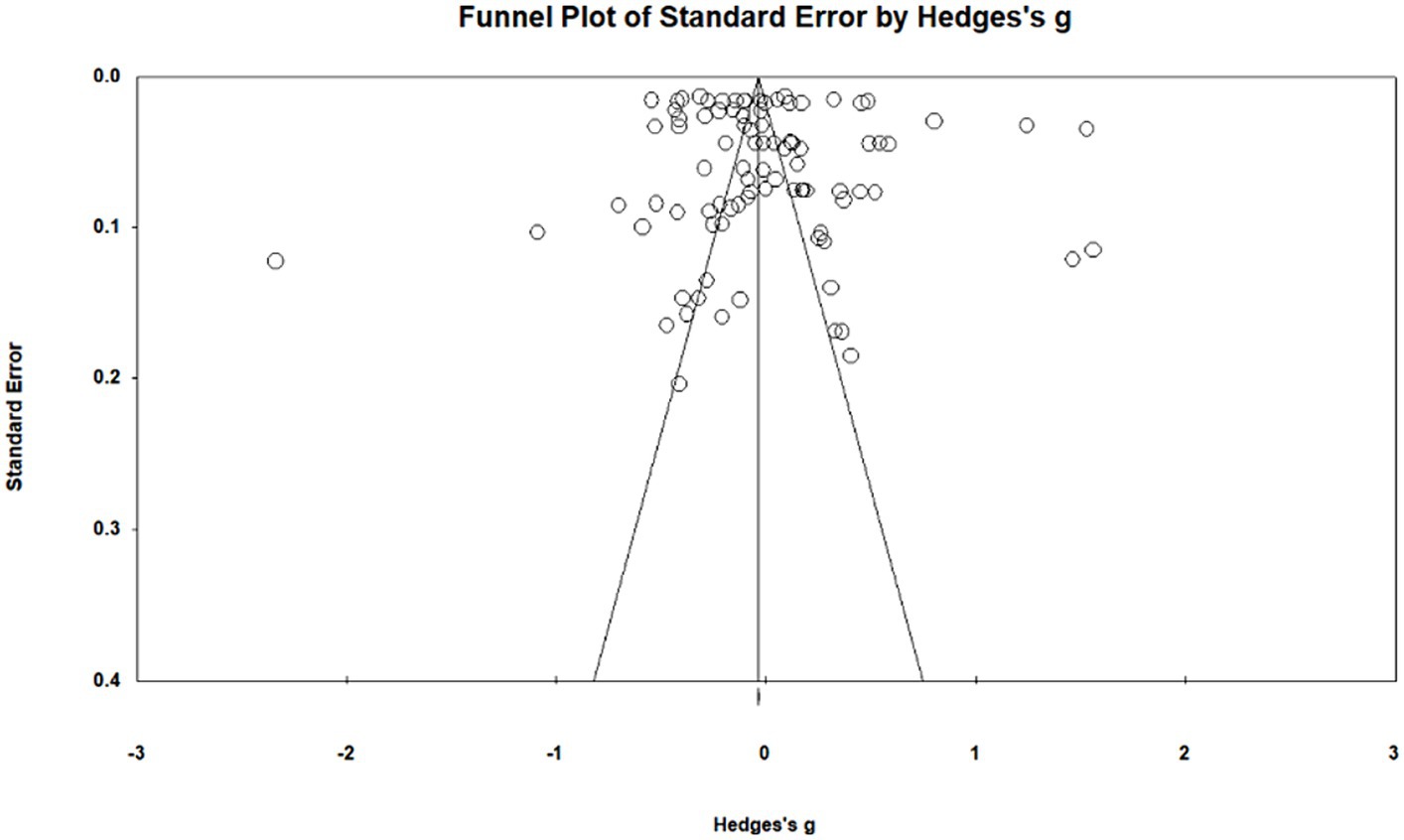

A publication bias analysis is first required before any specific data analysis of the sample literature can be conducted ( Viechtbauer, 2007 ). Qualitative funnel plots and quantitative Egger’s were used for publication bias tests. Based on the funnel plot indicating ( Figure 3 ) that the effect sizes of the study sample were focused on the upper middle region and more evenly distributed on both sides of the axis, it is initially judged that there is less likelihood of publication bias in the data. The study further utilized Egger’s method and the results of the data showed that t = 0.914 < 1.96 and p = 0.182 > 0.05, which satisfied the conditions of no publication bias ( Egger et al., 1997 ). In summary, the results of meta-analysis were less likely to be biased for publication ( Tables 1 , 2 ).

Figure 3 . Funnel plot.

Table 1 . Coding table for meta-analytic variables.

Table 2 . Summary of studies included in the meta-analysis.

Heterogeneity analysis

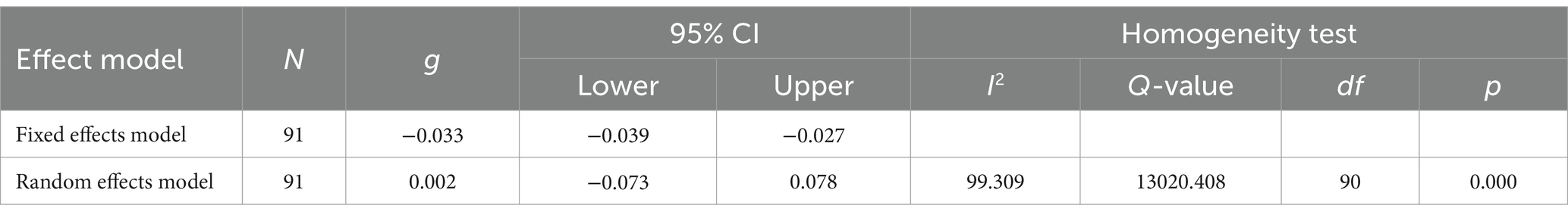

There may be differences between the different studies included due to a number of factors. To avoid the inability to combine effect sizes due to the presence of heterogeneity in the study, the I 2 statistic is generally used to determine the degree of heterogeneity in the sample, and thus to determine an effect model that is more appropriate for the study ( Higgins, 2003 ). When I 2 < 75%, a fixed effects model is used; when I 2 > 75%, a random effects model is used. According to the test results, I 2 = 99.309% > 75% and Q = 13020.408 ( p < 0.001), the study had high heterogeneity ( Table 3 ). Therefore, the random effect model would be chosen to analyze the effect of boarding school on student development in this study.

Table 3 . Heterogeneity test results.

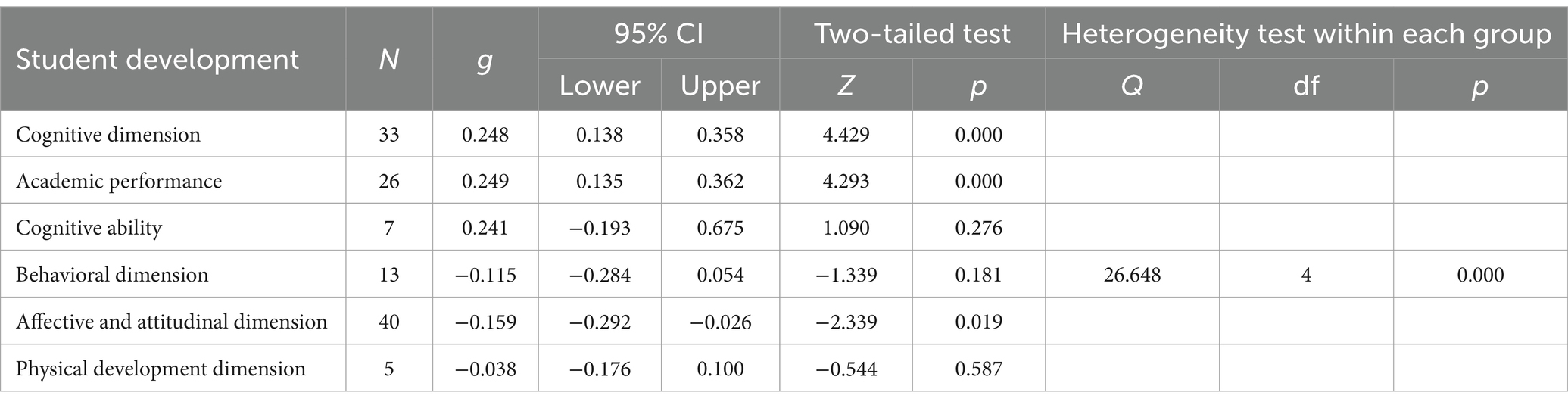

Main effects test

The results of the study indicated that boarding school was not a significant predictor of overall student development ( g = 0.002, 95%CI = [−0.073, 0.078], Z = 0.053, p > 0.05). The study further examined the effect of boarding school on different dimensions of student development. According to the results of Table 4 , the effect sizes from large to small were cognitive dimension ( g = 0.248, p < 0.001) > affective and attitudinal dimension ( g = |−0.159|, p < 0.05) > behavioral dimension ( g = |−0.115|, p > 0.05) > physical development dimension ( g = |−0.038|, p > 0.05). The results of the meta-analysis showed that boarding school had little effect on students’ overall development, but there were significant differences across the sub-dimensions. Specifically, boarding school has a moderate positive impact on students’ cognitive development and a small negative impact on students’ behavioral development, affective and attitudinal development, and physical development.

Table 4 . The overall impact of boarding school on student development.

Moderating effect test

Although the overall effect of boarding school on student development was small, there was significant heterogeneity in the effect size of different dimensions. Therefore, subgroup analyses are required. Moderating effect test was conducted using random effect model around different school stages, types of boarding school, and instruments.

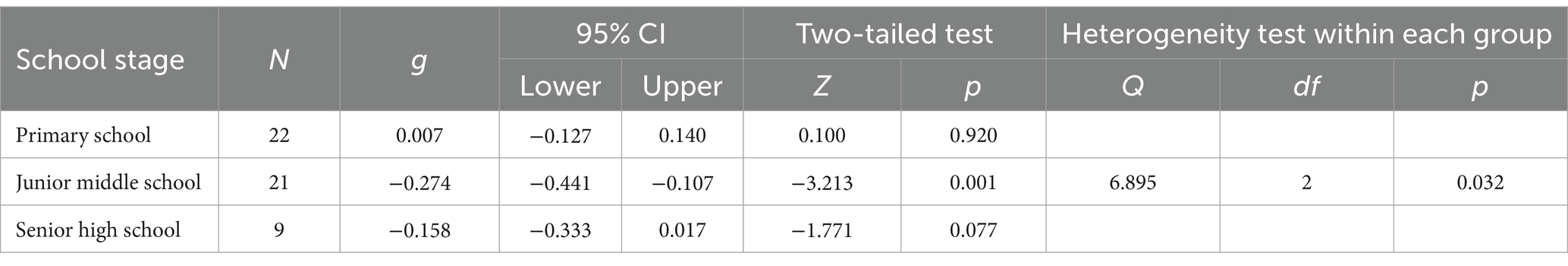

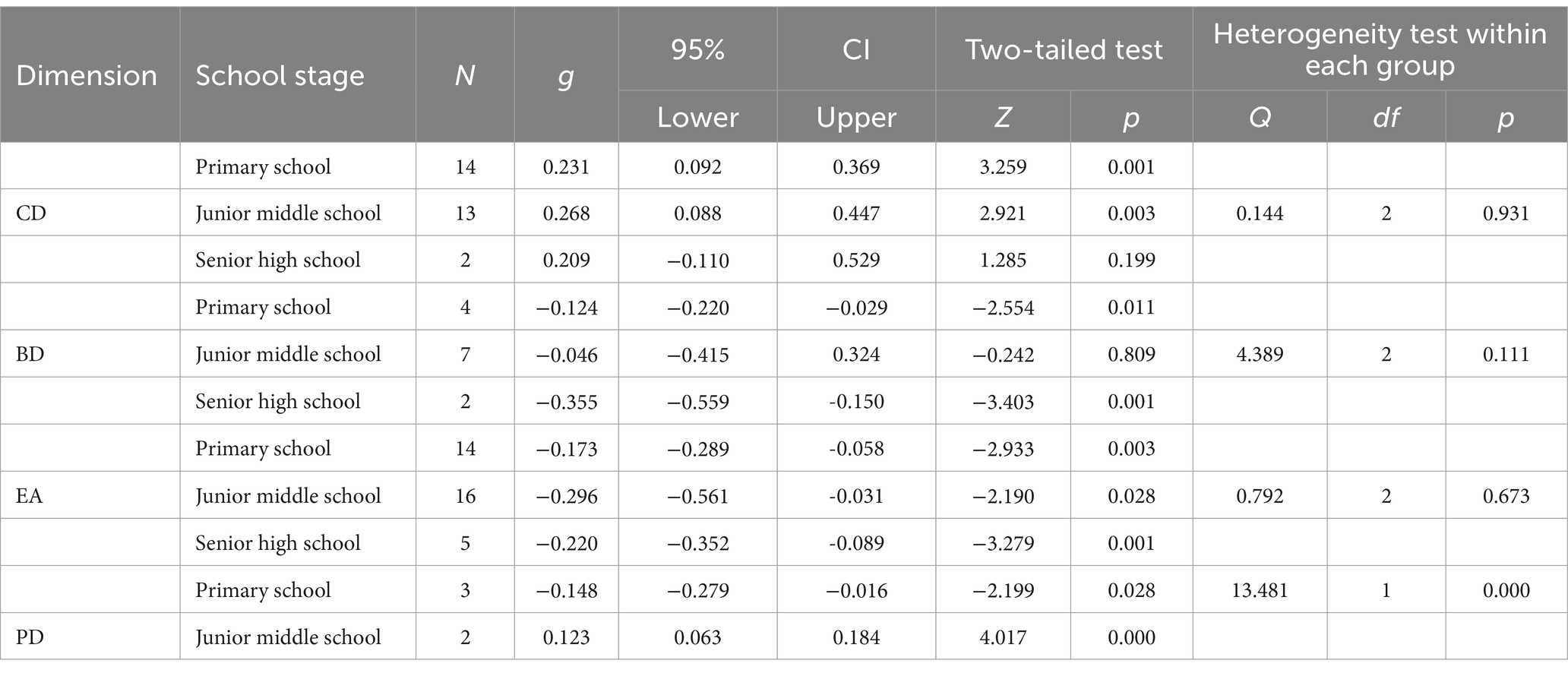

School stage

This study focuses on the impact of boarding school on the development of students in primary and secondary schools, so the school stages are coded into three groups: primary school, junior middle school and senior high school according to the current classification standards. Overall, there was a significant difference in the overall effect of different school stages on student development ( Q = 6.895, p < 0.05), with the effect strengths between school stages in the following order: junior middle school ( g = |−0.274|) > senior high school ( g = |−0.158|) > primary school ( g = 0.007) ( Table 5 ). Specifically, there was a significant difference in the effect of boarding school on students’ physical development in the physical development dimension ( Q = 13.481, p < 0.001). Among them, boarding school had a negative effect on the physical development of primary school students ( g = −1.48, p < 0.05), while it had a positive effect on the physical development of junior middle school students ( g = 0.123, p < 0.001). In addition, there was no significant difference in the cognitive dimension ( Q = 0.144, p = 0.931), behavioral dimension ( Q = 4.389, p = 0.111) and affective and attitudinal dimension ( Q = 0.792, p = 0.673) ( Table 6 ).

Table 5 . The moderating effect of school stages on boarding school and student development.

Table 6 . The moderating effect of sub-dimension across school stages.

Type of boarding school

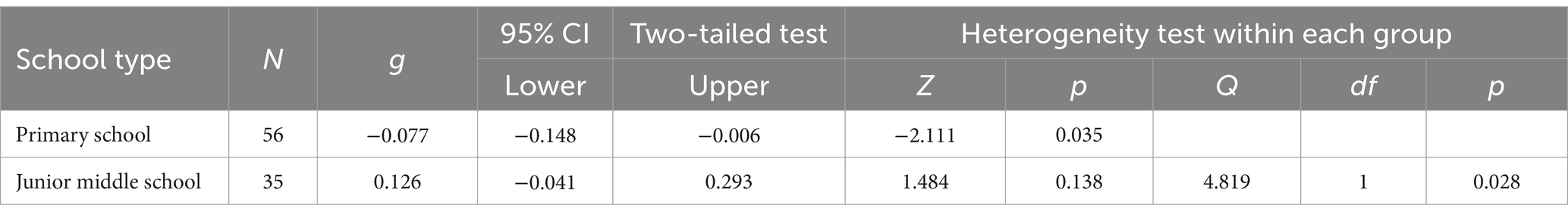

In this study, boarding schools were categorized into two types, rural boarding schools and urban boarding schools according to geography. Overall, there was a significant difference in the overall effect of different school types on student development ( Q = 4.819, p < 0.05), with effect strengths in the following order: urban boarding ( g = 0.126) > rural boarding ( g = |−0.077|) ( Table 7 ). Specifically, on the cognitive development dimension, there was a significant difference in the effect of boarding school on students’ cognitive development ( Q = 5.903, p < 0.05). In this case, boarding school had no significant effect on the cognitive development of rural boarding students ( g = 0.040, p < 0.05), while it produced a significant positive effect on the cognitive development of urban boarding students ( g = 0.289, p < 0.001). In addition, there was no significant difference in the development of students across school types by boarding school on either the behavioral dimension ( Q = 0.360, p = 0.549) or the affective and attitudinal dimension (Q = 0.251, p = 0.617) ( Table 8 ).

Table 7 . The moderating effect of school types on boarding school and student development.

Table 8 . The moderating effect of sub-dimension across school type.

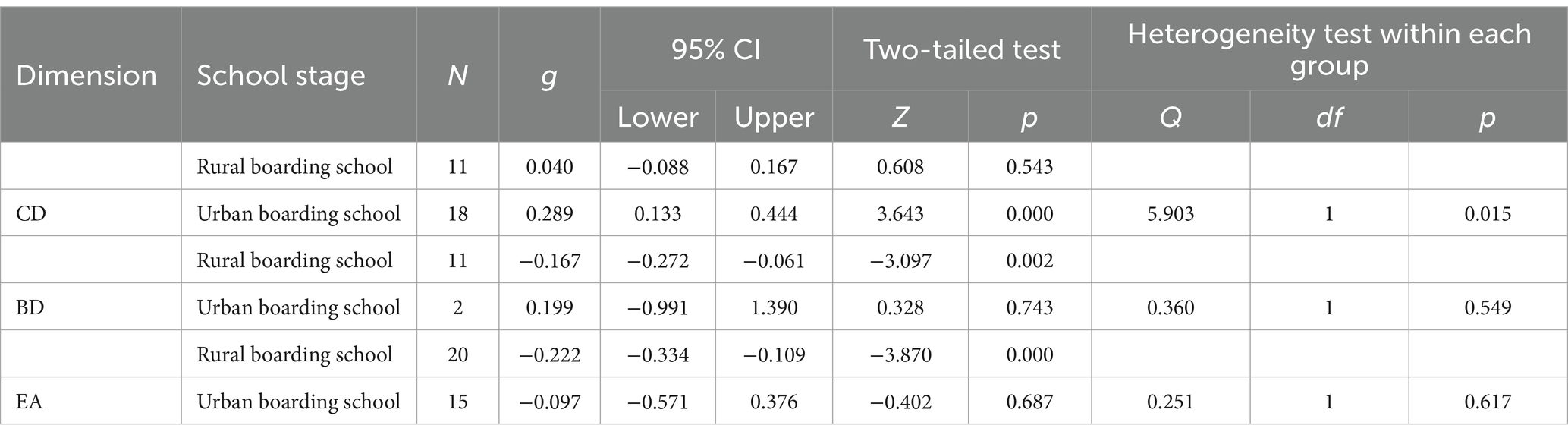

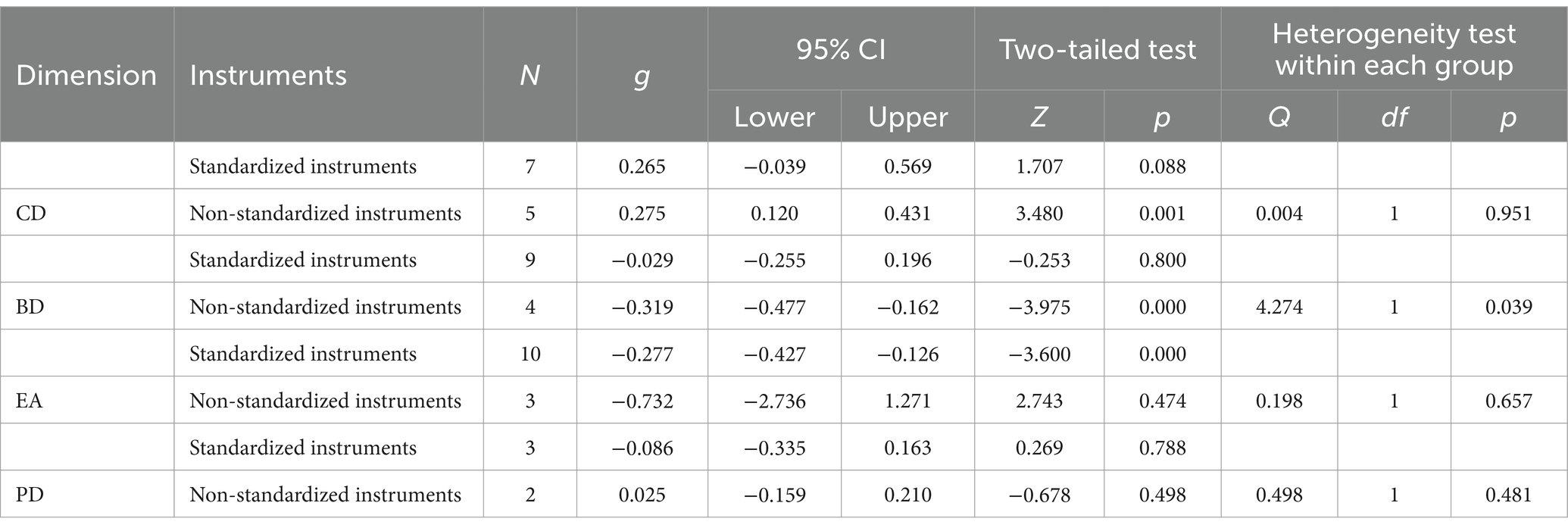

Instruments

The reliability and scientificity of the findings of quantitative research will be affected to some extent by the research tool. As can be seen from the sample of literature, most of the studies used standardized tests or maturity scales to measure student development, while a small number of studies developed self-administered questionnaires to report students’ development. Therefore, the instruments were categorized into standardized and non-standardized instruments to further explore the moderating effect of instruments on the relationship between boarding school and student development. Overall, there was no significant difference in the overall impact of the different instruments on student development ( Q = 0.128, p > 0.05). Specifically, on the behavioral dimension, there was a significant difference in the effect of boarding school on students’ behavioral development ( Q = 4.274, p < 0.05). In particular, there was no significant negative effect of boarding school on students’ behavioral development when standardized instruments were used ( g = −0.029, p > 0.05), while boarding school had a significant negative effect on students’ behavioral development when non-standardized instruments were used ( g = −0.319, p < 0.001; Table 9 ). In addition, there were no significant differences between the boarding school on the cognitive dimension ( Q = 0.004, p = 0.951), the affective and attitudinal dimension ( Q = 0.198, p = 0.657), and the physical development dimension ( Q = 0.498, p = 0.481) ( Table 10 ).

Table 9 . The moderating effect of instruments on boarding school and student development.

Table 10 . The moderating effect of sub-dimension across instruments.

The association between boarding school and the development of students

Compared with non-boarding school, boarding school has a smaller effect on student development ( g = 0.002, p > 0.05), which supports the third view that there is no significant predictive effect of boarding on student development ( Xiao et al., 2010 ; Martin et al., 2014 ; Sparks, 2015 ). The reason for this has much to do with the multidimensional concept of “student development.” There are many theories about the student development, the more typical ones are Social Learning Theory, Person-Environment Theory, Ecosystem Theory and so on. Together, these theories emphasize that student development is influenced by various factors, such as genetic, environmental, educational, and individuals. The boarding school provides students with a relatively closed learning environment, while integrating their studies and lives organically. In boarding schools, the extent to which students can be influenced by the environment in their interactions with it depends not only on the environment itself, but also on the students’ own initiative and motivation, school education, family environment and other factors ( Du et al., 2010 ).

The results of the data show that boarding school reached a statistically significant level on cognitive development and affective and attitudinal development of the students. Therefore, the study only focuses on these two sub-dimensions for discussion. Boarding school has a positive and significant predictive effect on students’ cognitive development ( g = 0.248, p < 0.001), which is consistent with previous findings ( Kennedy, 2010 ; Lu and Du, 2010 ; Gao, 2017 ). Boarding life promotes the development of students’ self-awareness and increases their independence and self-discipline ( Ma, 2012 ). These positive psychological qualities can be transferred to students’ learning, which in turn promotes the development of their cognitive abilities ( TABS, 2023 ). Boarding school presents a negative and significant predictive effect on students’ affective and attitudinal development ( g = −0.159, p < 0.05), which provides evidence for the second view ( Ye and Pan, 2007 ; Mander et al., 2014 ). When a student enters a boarding school, he or she will be faced with a completely new environment, as well as the stripping away of parental attachments. Attachment theory suggests that stable attachment relationships are critical for students’ academic, emotional, and social development ( Granot and Mayseless, 2001 ), while parents are the most important attachment relationship in students’ development ( Bosmans and Kerns, 2015 ). In addition, boarding schools often have a closed management model, which can easily lead to problems such as academic overload and depression among students ( Schaverien, 2010 ).

School stage as a moderator

The relationship between boarding school and student development is moderated by different school stages ( Q = 6.895, p < 0.05). Among them, boarding school has a significant negative effect on the development of junior middle school students, which may be related to the stage of physical and mental development that students are in ( Wang, 2015 ). According to Piaget’s Cognitive-developmental Theory, junior middle school students are in the transition from the stage of concrete operations to the stage of formal operations, a period in which students shift from perceptual thinking to logical thinking. With the increasing difficulty of knowledge acquisition, it is a great challenge for students’ cognitive development. In addition, students’ physical functions and forms continue to develop and improve during this period, but their psychology is in a semi-mature and emotionally unstable stage. Some students will face a crisis of self-identity and a conflict of role confusion ( Chen and Liu, 2019 ). Therefore, teachers should not only help students to stimulate their interest in learning, but also strengthen the support of families for students, and parents should be involved in students’ lives and learning.

Type of boarding school as a moderator

According to the results of the data, the type of boarding school plays a moderating role between boarding school and student development ( Q = 4.819, p < 0.05). Among them, rural boarding school has a negative effect on student development, which supports the views of Chen et al. (2018) , Lu et al. (2017) , Jiang and Xu (2020) , and others. The result that urban boarding school has a positive effect on student development supports Luo (2013) , Xu (2019) , Blau and Blau (2021) and others. The main reason for the disparity lies in the economic differences between urban and rural areas. From the students’ point of view, rural boarding students are more likely to come from rural areas, where their families are economically limited and their parents are generally less educated. From the perspective of schools, urban boarding schools have better accommodations, hardware facilities, and teachers than rural boarding schools ( Chen and Qi, 2010 ). Thus, it can be seen that boarding schools create variability in student development through differences in student population and level of schooling. In order to change the negative impact of the boarding school on rural students, the most important thing is to increase the total amount of financial input, and the gap between urban and rural areas is essentially an economic development gap. In addition, it is necessary to constantly expand the sources of funding to ensure the effective operation of the rural boarding school.

Instruments as a moderator

There is no significant difference in the effect of the instruments on student development under the boarding condition, which suggests that the relationship between boarding school and student development is not moderated by the instruments ( Q = 0.128, p > 0.05), but it is still of some analytical value. First, in terms of the specific effect size of the instruments, the effect size of using standardized instruments is smaller than that of non-standardized instruments. Although this difference does not reach the statistically significant level, it reflects the development trend of the two, that is, the measurement results of the non-standardized instruments are inflated compared with the standardized instruments. This is because standardized instruments are usually designed to be rigorous and preset the results within a certain range; whereas non-standardized instruments are usually a form of self-assessment and are more subjective, with flexible and open-ended results. Therefore, it can be presumed that standardized instruments are more realistic and reliable. Secondly, in terms of the scientific validity of the instruments, although the non-standardized instruments have not been recognized by the academic community and tested in practice like the mature standardized instruments, the operational procedures have been strictly followed and their reliability and validity tests have been tested, thus guaranteeing the scientificity and effectiveness of the instruments. This may also be one of the reason why the between-group effect failed to reach a statistically significant level.

Limitations and future directions

The study used a meta-analytic approach to systematically analyze the effects of boarding school on the overall development of primary and secondary school students as well as on different sub-dimensions. In addition, the study explored the moderating effects of different school stages, types of boarding school and instruments. However, there are some limitations to this study. First of all, the number of moderating variables included is limited. There are many factors that affect student development, such as gender, family economic situation, peer relationships, etc., and more moderating variables should be included in the future. Secondly, the results of the study are based on the literature sample, which will be affected by factors such as the quality of the literature sample, the sample size and the research period. Finally, student development is a comprehensive and multidimensional concept that should also include the development of students’ skills, literacy, information literacy, etc. ( Pan, 2019 ). Therefore, in the future, the validity of the findings of this study should be further verified by adopting a more scientific and comprehensive dimensionalization of the core concept of “student development.”

This study utilized a meta-analytic research methodology to explore the impact of boarding school on student development in primary and secondary schools. The results showed that boarding school had no significant predictive effect on students’ overall development, but it was a significant positive predictor of cognitive development and a significant negative predictor of affective and attitudinal development. The relationship between boarding school and student development was also moderated by the stage and type school. The conclusions of the study provide some reference significance for the subsequent theoretical research, and provide new insights and suggestions for the implementation and improvement of the boarding school in practice.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

ZZ: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. YF: Writing – original draft. YX: Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

The author (s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Anderson, L. W. (2009). Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives (Jiang, X. P, Luo, J. J, & Zhang, Q. M.) . Bei jing: Wai yu jiao xue yu yan jiu chu ban she.

Google Scholar

Behaghel, L., Chaisemartin, C., and Gurgand, M. (2017). Ready for boarding? The effects of a boarding school for disadvantaged students. Am. Econ. J-Appl Econ. 9, 140–164. doi: 10.1257/app.20150090

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Ben-David, A., and Erez-Darvish, T. (1997). The effect of the family on the emotional life of Ethiopian immigrant adolescents in boarding schools in Israel. Resid. Treat. Child. Yo. 15, 39–50. doi: 10.1300/j007v15n02_04

Blau, R., and Blau, P. (2021). Identity status, separation, and parent-adolescent relationships among boarding and day school students. Resid. Treat. Child. Yo. 38, 178–197. doi: 10.1080/0886571X.2019.1692757

Bosmans, G., and Kerns, K. A. (2015). Attachment in middle childhood: Progress and prospects. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2015, 1–14. doi: 10.1002/cad.20100

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Bozdoğan, A. E., Günaydın, E., and Okur, A. (2014). An examination of secondary school students’ academic achievement in science course and achievement scores in performance assignments with regard to different variables: a boarding school example. Particip. Educ. Res. 1, 95–105. doi: 10.17275/per.14.13.1.2

Chen, S. C. (2016). The relationship between mental health, social support and subjective well-being of boarding school students . Doctoral dissertation Qinghai Normal University.

Chen, Q., Chen, Y., and Zhao, Q. (2018). Impacts of boarding on primary school students’ mental health outcomes – instrumental-variable evidence from rural northwestern China. Econ. Hum. Biol. 39:100920. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2020.100920

Chen, Qi. & Liu, R. D. (2019). Dang Dai Jiao Yu Xin Li Xue . Beijing: Beijing shi fan da xue chu ban she

Chen, W. H., and Qi, Y. B. (2010). Survey and analysis of the “rural boarding system project” in Guizhou Province. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 38 , 1503–1506. doi: 10.13989/j.cnki.0517-6611.2010.03.162

Curto, V. E., and Fryer, R. G. (2014). The potential of urban boarding schools for the poor: evidence from seed. J. Labor Econ. 32, 65–93. doi: 10.1086/671798

Dong, S. H. (2012). Study on problem of boarding School in Rural Area in China . Master dissertation, Wuhan, HB, China: Central China Normal University.

Du, P., Zhao, R. Y., and Zhao, D. C. (2010). A study on the academic achievement and school adaptability of rural elementary school boarding students from five provinces and autonomous regions in Western China. J. Educ. Stud. 6, 84–91. doi: 10.14082/j.cnki.1673-1298.2010.06.015

Egger, M., Smith, G. D., Schneider, M., and Minder, C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315, 629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

Foliano, F., Green, F., and Sartarelli, M. (2019). Away from home, better at school. The case of a British boarding school. Econ. Educ. Rev. 73:101911. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2019.101911

Gao, L. Y. (2017). Study on the impacting of the boarding system on students’ development of rural junior high schools . (Kaifeng, HN, China: Doctoral dissertation Henan University).

Glass, G. V. (1976). Primary, secondary, and meta-analysis of research. Educ. Res. 5:3. doi: 10.2307/1174772

Granot, D., and Mayseless, O. (2001). Attachment security and adjustment to school in middle childhood. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 25, 530–541. doi: 10.1080/01650250042000366

Higgins, J. P. (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327, 557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

Jiang, N., and Xu, J. Q. (2020). The impact of boarding on the Children’s health in rural China. J. Educ. Econ. 36:9.

Kahane, R. (1988). Multicode organizations: a conceptual framework for the analysis of boarding schools. Sociol. Educ. 61:211. doi: 10.2307/2112440

Kennedy, J. (2010). A case study of the influence of a small residential high school environment on academic success . (MN, USA: Doctoral Dissertation Walden University).

Kleinfeld, D., and Bloom, J. (1977). Boarding schools: effects on the mental health of eskimo adolescents. Am. J. Psychiatry 134, 411–417. doi: 10.1176/ajp.134.4.411

Li, D. L. (2007). The study about the grade and psychological health of the boarders and day students . (Jinan, SD, China: Doctoral dissertation Shandong Normal University).

Li, C. H., and Lin, W. L. (2019). Are negative emotion contagious? --based on perspective of class social network. China. Econ. Q. 18, 597–616. doi: 10.13821/j.cnki.ceq.2019.01.09

Liu, C. J., Tian, S. Y., Xun, G. L., and Jia, Z. L. (2004). Comparative study on the mental health state between students in boarding and non-boarding senior middle school. Chin. J. Tissue Eng. Res. 8, 5782–5784. doi: 10.3321/j.issn:1673-8225.2004.27.019

Lu, K., and Du, Y. H. (2010). The effect of layout adjustment of rural schools on student achievement analysis based on the two-level value-added model. Tsinghua. J. Educ. 6:10. doi: 10.14138/j.1001-4519.2010.06.004

Lu, W., Song, Y. Q., and Liang, J. (2017). An empirical study on student bullying in boarding schools in rural China. J. Beijing. China. Norm. Univ (Soc Sci). 62, 5–17. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-0209.2017.05.001

Luo, X. R. (2013). Research on the mental health of urban boarding primary school students–survey and analysis based on a boarding primary School in Shanghai . (SH, China: Doctoral dissertation Shanghai Normal University).

Ma, X. Y. (2012). Comparative study on the learning adapt ability, mental health andacademic achievement between pupils in-boarding and non-boarding primary school . (HN, China: Doctoral dissertation Hunan Normal University).

Mander, D., Lester, L., and Cross, D. (2014). The social and emotional wellbeing, and mental health implications for adolescents transitioning to secondary boarding school. J. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 8, 131–140.

Martin, A. J., Papworth, B., Ginns, P., and Liem, G. A. (2014). Boarding school, academic motivation and engagement, and psychological well-being. Am. Educ. Res. J. 51, 1007–1049. doi: 10.3102/0002831214532164

Niknami, S., Zamani-Alavijeh, F., Shafiee, A., and Seifi, M. (2011). 208 comparison of psychological status of full boarding and day students in boarding schools. Asian J. Psychiatr. 4, S52–S53. doi: 10.1016/s1876-2018(11)60201-3

Pan, H. Y. (2019). Student development research in Chinese universities --a text analysis based on the self-evaluation report of the evaluation and evaluation of domestic universities . (Doctoral dissertation Dalian University of Technology.

Papworth, B. (2014). Attending boarding school: A longitudinal study of its role in students’ academic and non-academic outcomes . Doctoral dissertation The University of Sydney.

Pfeiffer, J. P., and Pinquart, M. (2014). Bullying in German boarding schools: a pilot study. School. Psychol. Int. 35, 580–591. doi: 10.1177/0143034314525513

Qiao, T. Y., and Di, L. (2014). The causal inference of Boarding’s effect in rural primary and secondary school education. J. Soc. Dev. 2:15.

Schaverien, J. (2010). Boarding school: the trauma of the ‘privileged’ child. J. Anal. Psychol. 49, 683–705. doi: 10.1111/j.0021-8774.2004.00495.x

Segal, C. (2013). Misbehavior, education, and labor market outcomes. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 11, 743–779. doi: 10.1111/jeea.12025

Shen, T. (2021). A study on the mechanism of the impact of boarding on children’s subjective well-being --a multi-case analysis based on rootedness theory. Child Study 34, 31–39.

Shi, Y. B., and Zhao, X. X. (2016). Which is more influential to rural dropout: parents’ migration for work or school boarding? --based on the empirical analysis of 1881 junior high school students from three Western provinces. J. Educ. Econ. 32, 78–83+90.

Sparks, S. D. (2015). Study: boarding schools don’t benefit all students. Educ. Week 34:5.

TABS. The Association of Boarding Schools. (2023). Available at: https://www.tabs.org/ .

Tan, L. (2020). A study on the relationship between self-worth, time management disposition and academic performance of urban and rural boarding and non-boarding pupils . (CQ, China: Doctoral dissertation Southwest University).

Verschueren, K., and Koomen, H. M. Y. (2012). Teacher–child relationships from an attachment perspective. Attach Hum. Dev. 14, 205–211. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2012.672260

Viechtbauer, W. (2007). Publication bias in meta-analysis: prevention, assessment and adjustments. Psychometrika 72, 269–271. doi: 10.1007/s11336-006-1450-y

Wang, Y. N. (2015). The investigation on mental health of boarders in ethnic minority Ares of Sichuan Province . (Mianyang, SC, China: Doctoral dissertation Southwest University of Science and Technology).

Wang, S. T., and Mao, Y. Q. (2015). The impact of boarding on social-emotional competence of left-behind children: an empirical study in 11 provinces and autonomous region in Western China. J. Edu. Stud. 11:10. doi: 10.14082/j.cnki.1673-1298.2015.05.014

White, M. A. (2004). An Australian co-educational boarding school: a sociological study of Anglo-Australian and overseas students’ attitudes from their own memoirs. Int. Educ. J. 5, 65–78.

Wu, H. Y., Ma, G. Y., and Jin, S. H. (2011). On the development of personality and sociality in rural elementary boarding schools. J. Hebei. Norm. Univ. 13:4.

Wu, M., Zhou, X. R., Ye, P. Q., and Sun, L. P. (2021). The influence of teacher-student relationship, peer relationship and parent-child relationship on the psychological capital among rural primary school boarders: a moderated mediation model. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 29, 230–235. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2021.02.003

Xiao, M., Ge, Y., and Cao, C. G. (2010). Correlation study about emotional management ability and mental health of the boarding countryside civilian workers’ children. Chin. J. School Health 31:3. doi: 10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2010.11.006

Xu, Z. Z. (2019). Study on the mathematical performance and lts influencing factors of boarders and non-boarders --based on six large-scale regional tests. Educ. Sci. Res. 30:6.

Xu, H. Q., Zhang, Q., Li, L., Zhang, F., Pan, H., Hu, X. Q., et al. (2014). Eating habits and nutritional status among boarding students in nutrition improvement program for rural area. Chin. J. School Health 35:4.

Yan, C. P., Fan, R., Du, W., Chen, H. H., and Li, Y. H. (2013). The security characteristics of rural young boarding pupils and its influencing factors. Chin. J. Behav. Med. Brain Sci. 22:3. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1674-6554.2013.09.022

Yang, P., and Yan, Z. Y. (2022). How boarding schools affect student mental health? J. East. China. Norm. Univ (Educ Sci). 40:16. doi: 10.16382/j.cnki.1000-5560.2022.08.007

Yao, S., and Gao, L. Y. (2018). Can large scale construction of boarding schools promote the development of students in rural area better? J. Educ. Econ. 34, 53–60.

Ye, J. Z., and Pan, L. (2007). A study of the emotional world of rural boarding primar school students. Educ. Sci. Res. 18:3.

Zhang, C. W. (2006). New exploration of rural boarding school operation model. Peoples. Educ. 57:2.

Zhang, D. S. (2020). Analysis on boarding and non-boarding students in junior MiddleSchool in Qianxi County . (HB, China: Doctoral dissertation Hebei Normal University).

Zhou, J. Y., and Xu, L. N. (2021). The effect of boarding on Students' academic achievement, cognitive ability and non-cognitive ability in junior high school. Educ. Sci. Res. 1, 53–59. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1009-718X.2021.05.010

Keywords: boarding school, student development, meta-analysis, primary and secondary school students, effect size

Citation: Zhong Z, Feng Y and Xu Y (2024) The impact of boarding school on student development in primary and secondary schools: a meta-analysis. Front. Psychol . 15:1359626. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1359626

Received: 21 December 2023; Accepted: 15 March 2024; Published: 28 March 2024.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2024 Zhong, Feng and Xu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yongqi Xu, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- Open access

- Published: 23 September 2023

The impact of boarding schools on the development of cognitive and non-cognitive abilities in adolescents

- Fang Chang 1 ,

- Yanan Huo 1 ,

- Songyan Zhang 1 ,

- Hang Zeng 1 &

- Bin Tang 1

BMC Public Health volume 23 , Article number: 1852 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

6919 Accesses

4 Altmetric

Metrics details

Since China adopted a policy to eliminate rural learning centers, boarding has become an important feature of the current rural student community. However, there is a lack of consensus on the impact of boarding schools on students' cognitive and non-cognitive development. This study investigates the effect of boarding schools on the development of cognitive and non-cognitive abilities of junior high school students in rural northwest China.

Using a sample of 5,660 seventh-grade students from 160 rural junior high schools across 19 counties, we identify a causal relationship between boarding and student abilities with the instrumental variables (IV) approach.

The results suggest that boarding positively influences memory and attention, while it has no significant effect on other cognitive abilities such as reasoning, transcription speed, and accuracy. Furthermore, we find no significant association between boarding and the development of non-cognitive skills.

Conclusions

Given the widespread prevalence of boarding schools in rural regions, our study highlights the growing importance of improving school management to promote the development of students’ cognitive abilities and integrating the development of non-cognitive or social-emotional abilities into students’ daily routines.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Human ability is composed of cognitive and non-cognitive components, both of which are crucial to an individual's life [ 1 , 2 ]. The influence of cognitive and non-cognitive abilities has been observed in various aspects of life, including academic performance, educational choices, wages, labor market outcomes, employment decisions, health behaviors, and social integration [ 3 , 4 , 5 ].

Cognitive and non-cognitive abilities are core components of human capital [ 1 , 2 , 6 ]. Cognitive abilities are the endowments for extracting, storing and utilizing information from the objective world, This encompasses skills such as logical reasoning, abstract thinking and memory [ 7 ], while non-cognitive abilities have emerged as a concept distinct from cognitive abilities, aiming to distinguish factors beyond cognitive itself. These encompass qualities such as motivation, authority, work norms, self-control, perseverance, and more [ 8 ]. Numerous researches have shown that cognitive and non-cognitive abilities play an important role in academic performance, educational decisions, wages, labor market performance, employment choices, health behaviors and social integration [ 1 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 8 , 9 ]. Prior research has revealed a considerable disparity between the cognitive abilities of rural and urban students, with urban students scoring significantly higher on word and mathematics tests by 0.75 and 0.54 standard deviations, respectively [ 6 , 10 ]. Rural students also tend to exhibit lower levels of non-cognitive skills, including depression, self-esteem, and values, with left-behind children experiencing even greater disadvantages [ 11 ].

Beginning in 2001, China adopted a policy to eliminate rural learning centers, leading to the consolidation of educational resources and the growth of rural boarding schools. By the end of 2016, 26.08 million rural students were enrolled as compulsory boarders, comprising 27.5% of the total student population. Of these, 16.66 million were boarding students in rural junior high schools, amounting to a boarding rate of 58.6% [ 12 ]. Therefore, a comprehensive evaluation of the cognitive and non-cognitive development of boarding students in rural areas has become essential.

Studies have shown that the communal learning environment in boarding schools can increase learning time, optimize teaching resources, and provide more opportunities for boarders to communicate with their teachers and peers [ 13 , 14 ]. However, boarding students may also be exposed to at-risk peers, which can have negative effects on their development [ 15 , 16 ]. Boarding can also cause stress for students as they are separated from their familiar surroundings and parents, which can be particularly significant during critical growth stages [ 17 ]. Consequently, there is a lack of consensus on the impact of boarding schools on students' cognitive and non-cognitive development.

Extant research on boarding schools has primarily focused on elite schools in developed countries, which have generally been associated with positive academic performance [ 18 ]. However, public boarding schools have been set up in many developed countries for marginalized groups, such as the SEED public boarding schools in the US and the Internet Excellence program in France. Quasi-experimental studies have shown that boarding has had a significant positive impact on the academic performance of disadvantaged students in reading and mathematics [ 19 ]. Similarly, rural boarding schools in France have positively impacted academic performance, particularly for outstanding boarders, with significant improvements in French and mathematics scores two years after enrollment [ 14 ]. Nonetheless, studies in Turkey have reported a negative correlation between boarding and academic performance in Grades 5 to 9 [ 15 ]. Boarding also has a significantly negative impact on students' mental health, with boarders displaying more problem behaviors, such as anxiety, depression, hostility, substance abuse, alcohol dependency, and school bullying [ 20 , 21 ]. Notably, the impact of boarding varies at different stages of development. For instance, Mander et al. (2015) found no significant differences in social, emotional, and psychological well-being between boarders and non-boarders in elementary schools [ 22 ]. However, boarders in secondary schools exhibited a higher incidence of emotional difficulties, depression, anxiety, and stress compared to non-boarders. Given the mixed evidence, it is crucial to carefully consider the potential positive and negative impacts of boarding, especially for disadvantaged students attending public boarding schools.

As boarding school enrollment continues to rise in China, researchers have investigated the effects of boarding on students' cognitive and non-cognitive abilities and reported conflicting findings. Qiao and Di (2014) found that boarding significantly improved rural students' performance in mathematics [ 23 ], while Mo et al. (2012) reported a significant negative effect of boarding on primary school students' math scores [ 24 ]. Similarly, Wang et al. (2016), Li et al. (2018), and Zhu et al. (2019) found that boarding had no significant impact on students' standardized math scores or even reduced their standardized language scores [ 25 , 26 , 27 ]. Most studies indicate that boarding has a negative impact on students' non-cognitive skills. Rural boarders are more likely to experience bullying, loneliness, and depression in schools and have lower self-esteem, resilience, and emotional intelligence than non-boarders [ 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 ]. Taken together, these results suggest that the effects of boarding on students' academic and non-academic outcomes are complex and may vary depending on a range of factors, including the type of boarding school, the students' developmental stage, and their socio-economic background.

This paper aims to contribute to the existing literature on the impact of boarding on rural students' cognitive and non-cognitive abilities in three ways. Firstly, the literature has primarily measured cognitive abilities using subject-specific scores, which may not fully capture the breadth of cognitive abilities. There are numerous studies on cognitive abilities in different disciplines. psychologists commonly differentiate between fluid intelligence, which emphasizes more general capacities such as logical reasoning and abstract thinking, and crystallized intelligence, which is related to the accumulation of concrete knowledge and experience [ 31 , 32 ]. Academic performance, such as math and reading tests is often used to measure crystallized intelligence [ 33 ]. Conversely, fluid intelligence is frequently assessed through quotient tests (IQ tests), exemplified bu tools like the WISC-IV and Raven's Standard Progressive Matrices [ 34 ]. To improve accuracy and precision in measuring cognitive abilities, this paper utilizes the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC), Raven's Standard Progressive Matrices, and standardized mathematics scores. Secondly, the literature has relied on self-administered questionnaires to measure non-cognitive abilities, which may lack comprehensiveness and comparability. In contrast, this paper uses the Big Five Personality Inventory to measure non-cognitive abilities accurately [ 35 ]. Finally, prior studies have examined the effects of boarding on cognitive or non-cognitive abilities separately, which prevents a comprehensive assessment of the impact of boarding on students' human capital.

This study uses an instrumental variable approach to address endogeneity issues and analyzes data from 160 junior high schools in rural northwest China to illustrate the effects of boarding on students' cognitive and non-cognitive abilities. The results indicate a significant positive effect of boarding on the cognitive abilities of rural junior high school students, particularly in memory and attention, areas associated with fluid intelligence. However, boarding has no significant impact on the non-cognitive abilities of rural students. Furthermore, we provide evidence of heterogeneity in the impact of boarding on cognitive and non-cognitive abilities by gender. We also find a significant positive effect on the cognitive abilities of left-behind children and students from families with better socioeconomic status.

Participants

We conducted our study on first-year rural high school (seventh grade) students in three prefectures from two provinces in northwest China. These provinces were below the national median in terms of GDP, according to the National Bureau of Statistics of China (2015). Hence, the sample of rural students in these provinces can be considered representative of students in low-income areas in rural China.

We constructed our sample in two steps. First, we selected 23 counties from three prefectures, two counties with more developed economic status were excluded, and the remaining were included. Second, we obtained a list of all 496 junior high schools from the counties in Step 1. After excluding non-rural schools and schools with less than 20 students in the seventh grade (to address potential sample attrition or school merger issues), we obtained a final sample containing 5,660 seventh-grade students from 160 schools (see Table 1 ).

The sample was collected in two phases. The first phase was carried out in 2015, which involved administering tests to collect information on basic details of the sample students, mathematics teachers, and schools using questionnaires. Mathematics scores of students were also collected through tests (see Table 2 ). In the second phase, conducted in 2016, additional tests were administered, which included more Raven's tests, Wechsler tests, the Big Five Personality test, and the Perseverance Scale (see Table 2 ).

The data collection involved three steps: (1) recruiting and training researchers, (2) conducting questionnaire tests in schools, and (3) administering cognitive and non-cognitive ability tests. For (1), the project team recruited college students as researchers and provided uniform training and simulation exercises to ensure recruited researchers mastered standardized operations of the study, thus reducing measurement errors caused by inconsistent implementation by researchers. For (2), researchers organized students to take standardized math tests and questionnaires, which were developed by the project team in collaboration with the best secondary school teachers and calibrated to match the academic level appropriate for seventh-grade rural students. All sample schools used standardized math tests with identical questions assigned by the project team and proctored by researchers on-site. Researchers also conducted one-on-one questionnaire interviews with principals and mathematics teachers. In (3), cognitive ability tests included Raven's test and Wechsler's test. Raven's test was administered in a group and took approximately 45 min. The Wechsler test needed to be conducted one-on-one and required highly trained personnel, participants therefore received training in professional institutions. Additionally, the project team organized several practical exercises in non-sample schools to ensure the accuracy and consistency of the Wechsler test. Given the significant testing and time costs of the Wechsler test, three students from each sample class were randomly selected to take the Wechsler test individually. Students are selected based on their mathematics scores in the first research sample class, which were rank ordered into three groups: high, medium, and low; one student from each group was randomly selected for the Wechsler's test. The rest of the class took the Raven's test. The non-cognitive skills component primarily consisted of the Big Five personality test and the Perseverance Scale test, both of which were included in the student questionnaire.

- Cognitive ability

The objective of this research is to investigate students' cognitive abilities, measured using three tests: the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Fourth Edition (WISC-IV), Raven's Standard Progressive Matrices (Raven's IQ test), and a mathematics test. Cattell's (1987) suggested that cognitive abilities are divisible into two categories: crystallized intelligence and fluid intelligence [ 36 ]. The former pertains to skills attained through experience and knowledge, such as vocabulary, calculation, and verbal comprehension, whereas the latter refers to neural development, including perception, memory, and reasoning ability.

The WISC-IV is a tool for assessing intelligence in children aged 6 to 16 and comprises four indices: verbal comprehension, perceptual reasoning, working memory, and processing speed, along with the total IQ score [ 37 ]. The Chinese version of the WISC-IV short-form scale was employed in this research, which contains four subtests representing the four indices [ 38 ]. Footnote 1 The four subtests utilized for estimating the WISC IQ score were similarities, digit span, coding, and matrix reasoning. Similarities is designed to capture crystallized intelligence, while digit span, coding, and matrix reasoning are intended to measure fluid intelligence [ 39 ]. The aggregated WISC IQ score was used in the regression analysis.

The Raven's IQ test is a nonverbal test of intelligence that consists of pictorial questions related to spatial reasoning and pattern matching, which are designed to assess observational and thinking ability [ 40 ]. The test is culture-, language-, and age-neutral and consists of 60 questions that can be converted into IQ scores based on normative patterns. It is defined to capture fluid intelligence and was used for robustness testing in this study [ 31 ]. Footnote 2

The mathematics test, administered to all students in the sample, was developed by experienced secondary school mathematics teachers based on the standard high school syllabus. The test captures crystallized intelligence and was used for robustness testing in this study [ 33 ]. Several pre-studies of the questions were carried out by the research team to assess their suitability.

- Non-cognitive ability

Non-cognitive abilities represent a fundamental component of human capital and can be examined through various skills and traits, including self-control, self-esteem, self-confidence, due diligence, perseverance, self-awareness, and communication skills [ 45 ]. We employed the Big Five personality traits and the Short Grit Scales as measures of non-cognitive abilities.

DeYoung's Big Five personality traits consist of neuroticism, agreeableness, conscientiousness, extraversion, and openness, which capture diverse aspects of personality. Neuroticism assesses emotional instability and sensitivity, such as anxiety, hostility, depression, self-consciousness, impulsivity, and vulnerability. Extraversion captures interpersonal skills, positive affect, and energy levels. Openness refers to the imagination and intellectual curiosity as reflected in personal fantasy, aesthetics, feelings, actions, ideas, and values. Agreeableness evaluates how a person interacts with others through levels of trust, frankness, altruism, submissiveness, humility, and gentleness. Finally, conscientiousness assesses competence, order responsibility, effortful achievement, self-discipline, and thoughtfulness [ 46 ]. The Big Five personality traits have been widely studied and are recognized as being stable across different languages, disciplines, and raters [ 47 , 48 ].

The Short Grit Scale, developed by Duckworth et al. (2007), measures perseverance and passion for long-term goals [ 49 ]. This scale consists of eight questions that evaluate student attitudes and behaviors towards long-term goals, such as the tendency to prioritize new ideas over existing plans [ 50 ]. The Short Grit Scale has demonstrated strong internal consistency, test–retest stability, and high predictive validity [ 51 ]. Grit is considered a facet of Big Five conscientiousness and has gained recent attention in the literature on human achievement. In this study, we utilized it for robustness testing.

Model design

Consider a statistical model that links a student's cognitive and non-cognitive abilities, boarding status, and other determinants of ability as represented by:

where \({Y}_{jis}\) denotes the cognitive and non-cognitive abilities of student i in school s in county j; \(Boardin{g}_{jis}\) is an indicator of the student's boarding status (1 if boarding, 0 otherwise), and \({W}_{jis}\) is a set of exogenous covariates that includes student (e.g., age and gender), family (e.g., parental education), and school (e.g., teacher qualifications and school facilities) characteristics; \({\mu }_{j}\) is county fixed effect; and the error term \({\varepsilon }_{jis}\) captures the influence of all unobserved factors.

Equation (1) may be subject to endogeneity issues for two main reasons. First, reverse causality may arise where students with lower cognitive abilities or academic performance could be more likely to choose boarding [ 14 ]. This concern is particularly true in cases such as the French excellent boarding school program, which is designed to provide elite education for disadvantaged groups. In contrast, boarding schools in rural China aim to integrate educational resources and are more likely to be chosen because of the distance between the student's home and school [ 26 , 27 , 52 ]. Therefore, reverse causality may not be a problem in this study. Second, omitted variables may also pose a problem, given that factors that affect students' cognitive and non-cognitive abilities may exist at multiple levels, and crucial indicators such as genetic factors and parental emotional involvement may be difficult to measure [ 27 , 53 , 54 , 55 ].

To address these problems, we use the standard instrumental variables (IV) approach to identify an exogenous source of variation in one's boarding status. The proportion of boarders of all students in a particular school is used as an instrumental variable for boarding. This strategy is based on the assumption that the proportion of boarders is a strong predictor of one's boarding status, because a higher proportion of boarders within a school indicates a higher likelihood for students to become boarders in that school. We employ a two-stage least squares (2SLS) framework to estimate Eq. (1) and the following first-stage equation.

The first-stage equation:

The second stage equation:

where \(Boardin{g}_{jis}\) is the proportion of boarders. The definitions of other variables are the same as in Eq. (1).

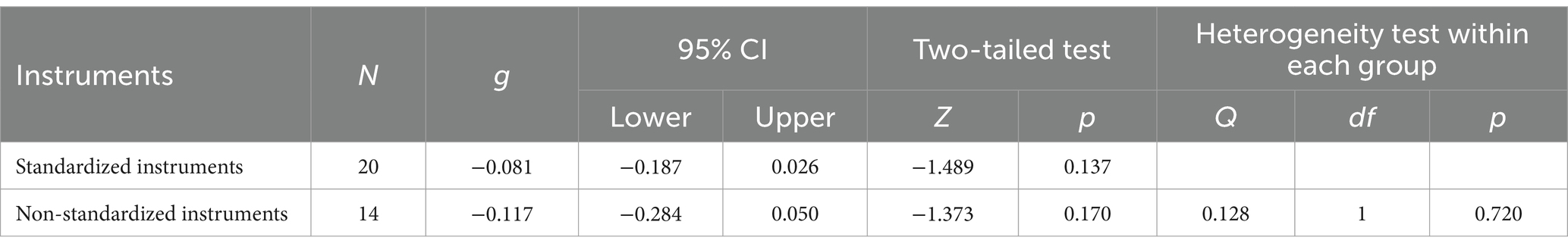

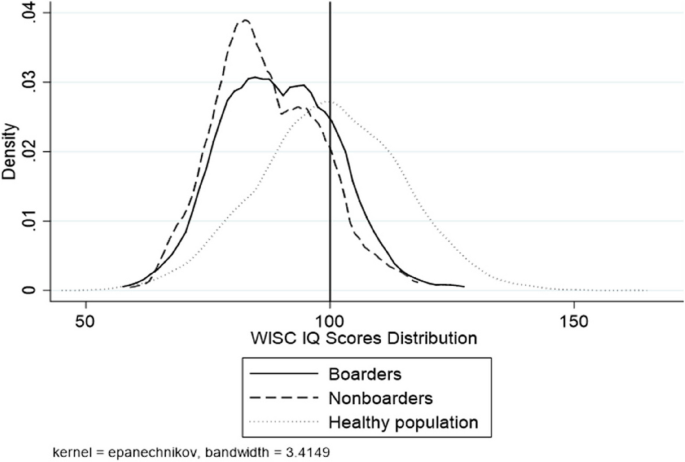

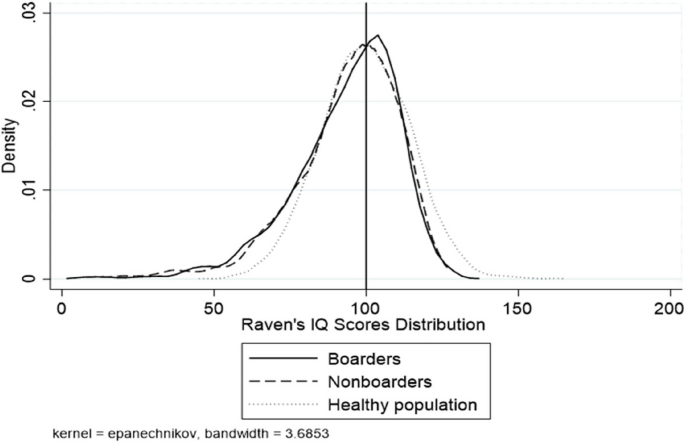

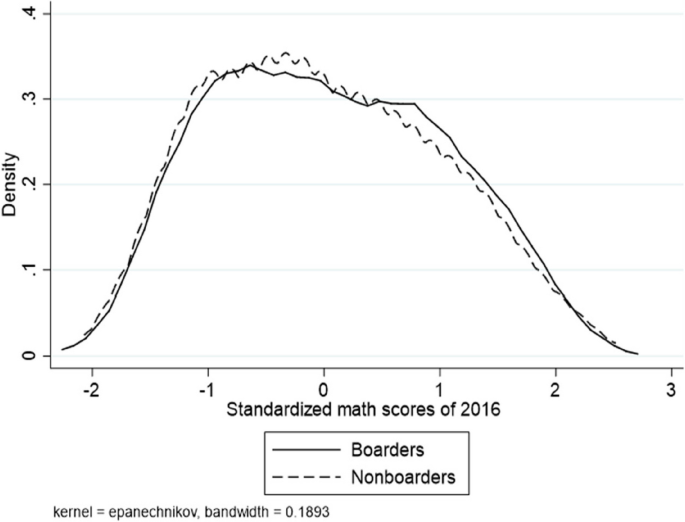

Distribution of cognitive abilities and non-cognitive abilities

Figure 1 shows the distribution of WISC-IV scores in our sample. The density distribution of WISC-IV scores is right-skewed for both boarding and non-boarding students compared to the norm, indicating a relatively high proportion of students with cognitive delays in our sample. Boarding students exhibit a less right-skewed distribution of WISC-IV scores compared to non-boarding students, suggesting that boarding students have higher WISC-IV scores on average. Fig. 2 shows the density distribution of Raven's IQ scores for the sample students. The estimated IQ scores on Raven's test for both boarding and non-boarding samples are not significantly different from the norm. Moreover, there is no significant difference between the Raven's IQ scores of boarding and non-boarding students. Finally, Fig. 3 illustrates the density distribution of standardized math scores for the sample students, suggesting that there is no significant difference between the boarding and non-boarding students.

Distribution of WISC IQ scores for sample students and a healthy population. The WISC IQ scores density distribution in the healthy population is a normal distribution with a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15

Distribution of Raven’s IQ scores for sample students and a healthy population. The Raven’s IQ scores density distribution in the healthy population is a normal distribution with a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15

Distribution of standardized math scores for sample students. Math scores are standardized

Table 3 presents the differences in cognitive and non-cognitive abilities between boarding and non-boarding students. The results indicate that boarders' WISC-IV scores were 2.45 points higher than non-boarders, significant at the 5% level, and boarders' fluid intelligence scores were 0.363 points higher than non-boarder, similarly significant at the 5% level. Boarders also scored higher on the matrix reasoning scale by 0.82 points at the 1% significance level. Additionally, boarders' standardized math scores were statistically significantly higher than non-boarders. In terms of non-cognitive skills, boarders scored higher in extraversion by 0.042, but lower in agreeableness by 0.042 compared to non-boarders.

Table 4 verifies the representativeness of the WISC-IV-tested students in the sample. We examine the differences in student characteristics between those who took the test and those who did not. The results indicate no significant differences in individual characteristics, family characteristics, and baseline math scores between the two groups.

Impact of boarding on cognitive abilities

Table 5 presents an analysis of the impact of boarding on cognitive abilities among rural students, specifically focusing on WISC IQ scores, fluid intelligence, and crystal intelligence. Using ordinary least squares (OLS) estimates in columns 1, 3, and 5, the results show that boarding does not have a significant effect on students' cognitive abilities. To further examine the causal relationship between boarding and cognitive abilities, two-stage least squares (2SLS) estimates are presented in columns 2, 4, and 6, and the findings indicate that boarding has no significant impact on WISC IQ scores, fluid intelligence, and crystal intelligence. The first stage regression has a high F-statistic of 41.284, indicating the exclusion of weak instrumental variables. To better understand how boarding affects students' cognitive abilities, we also estimated the impacts of boarding on the four subdimensions of WISC IQ scores, which are similarities, digit span, coding, and matrix reasoning. The results presented in Table 6 . The 2SLS estimates for boarding on students’ scores in digit span has a parameter estimate of 2.024, significant at the 5% level. Since scores in digit span is a test of attention and memory, the result highlights the positive impact of boarding on students' performance in this particular cognitive dimension.

Impact of boarding on students' non-cognitive abilities

Table 7 presents the effects of boarding on the personality traits of rural students, encompassing extraversion, agreeableness, dutifulness, neuroticism, and openness. The OLS results in columns (1), (3), (5), (7), and (9) suggest that while there is a positive relationship between boarding and the extraversion of rural students, the IV results indicate that boarding does not have a statistically significant effect on any of the five personality traits examined. Therefore, we conclude that boarding does not have any significant effects on the non-cognitive abilities of rural students.

Robustness test

To enhance the robustness of the research findings, we conducted additional regression analyses. First, we added the bootstrap method to the original instrumental variables method to re-estimate the impact of boarding on students' cognitive and non-cognitive abilities. The bootstrap method involves treating the observed sample as the entire population, and repeatedly resampling with replacement from the original sample to estimate the sampling distribution. This approach can provide an estimate of the distribution without introducing bias. In this paper, we conducted 1000 bootstrap samples and then used the instrumental variables method for estimation, which can provide more robust standard errors. Tables 8 and 9 show the results, which indicate that boarding still has a significant positive effect at the 10% level on students' scores in digit span and no significant effect on students' non-cognitive abilities, which is consistent with the results above.

Second, we performed robustness tests using Raven's IQ, standardized math, and grit scores as additional measures of cognitive and non-cognitive abilities. Raven's IQ and standardized math scores are measures of fluid and crystal intelligence, respectively. The results in Table 10 suggest that boarding does not have a significant effect on students' Raven's IQ and standardized math scores, which are consistent with previous findings. Grit is closely related to conscientiousness in the Big Five personality traits, and although the two are not identical, they share strong similarities such as diligence and perseverance [ 56 ]. It has also been shown that grit is a more refined measure of conscientiousness [ 57 , 58 ]. However, columns (5) and (6) of Table 10 show that boarding does not have a significant effect on students' grit scores, which are consistent with the previous results.

Heterogeneity analysis