What is Critical Thinking in Nursing? (With Examples, Importance, & How to Improve)

Successful nursing requires learning several skills used to communicate with patients, families, and healthcare teams. One of the most essential skills nurses must develop is the ability to demonstrate critical thinking. If you are a nurse, perhaps you have asked if there is a way to know how to improve critical thinking in nursing? As you read this article, you will learn what critical thinking in nursing is and why it is important. You will also find 18 simple tips to improve critical thinking in nursing and sample scenarios about how to apply critical thinking in your nursing career.

What is Critical Thinking in Nursing?

4 reasons why critical thinking is so important in nursing, 1. critical thinking skills will help you anticipate and understand changes in your patient’s condition., 2. with strong critical thinking skills, you can make decisions about patient care that is most favorable for the patient and intended outcomes., 3. strong critical thinking skills in nursing can contribute to innovative improvements and professional development., 4. critical thinking skills in nursing contribute to rational decision-making, which improves patient outcomes., what are the 8 important attributes of excellent critical thinking in nursing, 1. the ability to interpret information:, 2. independent thought:, 3. impartiality:, 4. intuition:, 5. problem solving:, 6. flexibility:, 7. perseverance:, 8. integrity:, examples of poor critical thinking vs excellent critical thinking in nursing, 1. scenario: patient/caregiver interactions, poor critical thinking:, excellent critical thinking:, 2. scenario: improving patient care quality, 3. scenario: interdisciplinary collaboration, 4. scenario: precepting nursing students and other nurses, how to improve critical thinking in nursing, 1. demonstrate open-mindedness., 2. practice self-awareness., 3. avoid judgment., 4. eliminate personal biases., 5. do not be afraid to ask questions., 6. find an experienced mentor., 7. join professional nursing organizations., 8. establish a routine of self-reflection., 9. utilize the chain of command., 10. determine the significance of data and decide if it is sufficient for decision-making., 11. volunteer for leadership positions or opportunities., 12. use previous facts and experiences to help develop stronger critical thinking skills in nursing., 13. establish priorities., 14. trust your knowledge and be confident in your abilities., 15. be curious about everything., 16. practice fair-mindedness., 17. learn the value of intellectual humility., 18. never stop learning., 4 consequences of poor critical thinking in nursing, 1. the most significant risk associated with poor critical thinking in nursing is inadequate patient care., 2. failure to recognize changes in patient status:, 3. lack of effective critical thinking in nursing can impact the cost of healthcare., 4. lack of critical thinking skills in nursing can cause a breakdown in communication within the interdisciplinary team., useful resources to improve critical thinking in nursing, youtube videos, my final thoughts, frequently asked questions answered by our expert, 1. will lack of critical thinking impact my nursing career, 2. usually, how long does it take for a nurse to improve their critical thinking skills, 3. do all types of nurses require excellent critical thinking skills, 4. how can i assess my critical thinking skills in nursing.

• Ask relevant questions • Justify opinions • Address and evaluate multiple points of view • Explain assumptions and reasons related to your choice of patient care options

5. Can I Be a Nurse If I Cannot Think Critically?

The Value of Critical Thinking in Nursing

- How Nurses Use Critical Thinking

- How to Improve Critical Thinking

- Common Mistakes

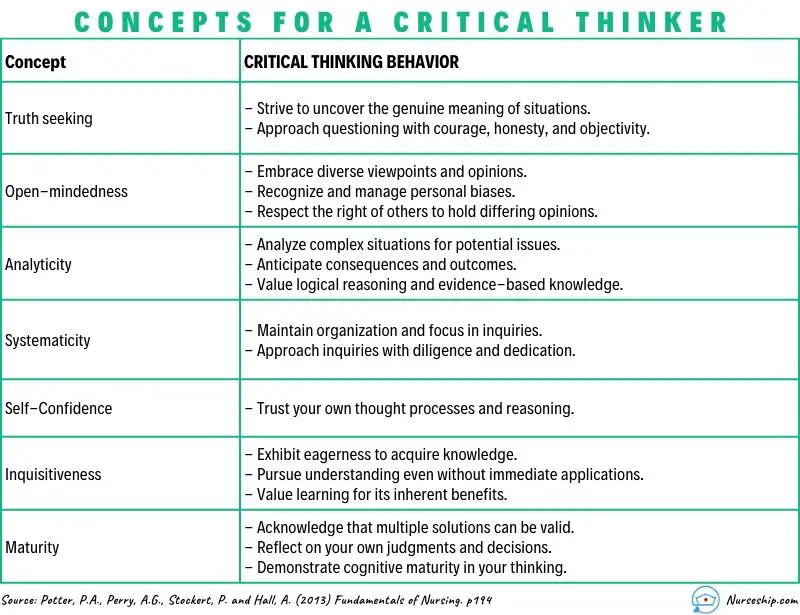

Some experts describe a person’s ability to question belief systems, test previously held assumptions, and recognize ambiguity as evidence of critical thinking. Others identify specific skills that demonstrate critical thinking, such as the ability to identify problems and biases, infer and draw conclusions, and determine the relevance of information to a situation.

Nicholas McGowan, BSN, RN, CCRN, has been a critical care nurse for 10 years in neurological trauma nursing and cardiovascular and surgical intensive care. He defines critical thinking as “necessary for problem-solving and decision-making by healthcare providers. It is a process where people use a logical process to gather information and take purposeful action based on their evaluation.”

“This cognitive process is vital for excellent patient outcomes because it requires that nurses make clinical decisions utilizing a variety of different lenses, such as fairness, ethics, and evidence-based practice,” he says.

How Do Nurses Use Critical Thinking?

Successful nurses think beyond their assigned tasks to deliver excellent care for their patients. For example, a nurse might be tasked with changing a wound dressing, delivering medications, and monitoring vital signs during a shift. However, it requires critical thinking skills to understand how a difference in the wound may affect blood pressure and temperature and when those changes may require immediate medical intervention.

Nurses care for many patients during their shifts. Strong critical thinking skills are crucial when juggling various tasks so patient safety and care are not compromised.

Jenna Liphart Rhoads, Ph.D., RN, is a nurse educator with a clinical background in surgical-trauma adult critical care, where critical thinking and action were essential to the safety of her patients. She talks about examples of critical thinking in a healthcare environment, saying:

“Nurses must also critically think to determine which patient to see first, which medications to pass first, and the order in which to organize their day caring for patients. Patient conditions and environments are continually in flux, therefore nurses must constantly be evaluating and re-evaluating information they gather (assess) to keep their patients safe.”

The COVID-19 pandemic created hospital care situations where critical thinking was essential. It was expected of the nurses on the general floor and in intensive care units. Crystal Slaughter is an advanced practice nurse in the intensive care unit (ICU) and a nurse educator. She observed critical thinking throughout the pandemic as she watched intensive care nurses test the boundaries of previously held beliefs and master providing excellent care while preserving resources.

“Nurses are at the patient’s bedside and are often the first ones to detect issues. Then, the nurse needs to gather the appropriate subjective and objective data from the patient in order to frame a concise problem statement or question for the physician or advanced practice provider,” she explains.

Top 5 Ways Nurses Can Improve Critical Thinking Skills

We asked our experts for the top five strategies nurses can use to purposefully improve their critical thinking skills.

Case-Based Approach

Slaughter is a fan of the case-based approach to learning critical thinking skills.

In much the same way a detective would approach a mystery, she mentors her students to ask questions about the situation that help determine the information they have and the information they need. “What is going on? What information am I missing? Can I get that information? What does that information mean for the patient? How quickly do I need to act?”

Consider forming a group and working with a mentor who can guide you through case studies. This provides you with a learner-centered environment in which you can analyze data to reach conclusions and develop communication, analytical, and collaborative skills with your colleagues.

Practice Self-Reflection

Rhoads is an advocate for self-reflection. “Nurses should reflect upon what went well or did not go well in their workday and identify areas of improvement or situations in which they should have reached out for help.” Self-reflection is a form of personal analysis to observe and evaluate situations and how you responded.

This gives you the opportunity to discover mistakes you may have made and to establish new behavior patterns that may help you make better decisions. You likely already do this. For example, after a disagreement or contentious meeting, you may go over the conversation in your head and think about ways you could have responded.

It’s important to go through the decisions you made during your day and determine if you should have gotten more information before acting or if you could have asked better questions.

During self-reflection, you may try thinking about the problem in reverse. This may not give you an immediate answer, but can help you see the situation with fresh eyes and a new perspective. How would the outcome of the day be different if you planned the dressing change in reverse with the assumption you would find a wound infection? How does this information change your plan for the next dressing change?

Develop a Questioning Mind

McGowan has learned that “critical thinking is a self-driven process. It isn’t something that can simply be taught. Rather, it is something that you practice and cultivate with experience. To develop critical thinking skills, you have to be curious and inquisitive.”

To gain critical thinking skills, you must undergo a purposeful process of learning strategies and using them consistently so they become a habit. One of those strategies is developing a questioning mind. Meaningful questions lead to useful answers and are at the core of critical thinking .

However, learning to ask insightful questions is a skill you must develop. Faced with staff and nursing shortages , declining patient conditions, and a rising number of tasks to be completed, it may be difficult to do more than finish the task in front of you. Yet, questions drive active learning and train your brain to see the world differently and take nothing for granted.

It is easier to practice questioning in a non-stressful, quiet environment until it becomes a habit. Then, in the moment when your patient’s care depends on your ability to ask the right questions, you can be ready to rise to the occasion.

Practice Self-Awareness in the Moment

Critical thinking in nursing requires self-awareness and being present in the moment. During a hectic shift, it is easy to lose focus as you struggle to finish every task needed for your patients. Passing medication, changing dressings, and hanging intravenous lines all while trying to assess your patient’s mental and emotional status can affect your focus and how you manage stress as a nurse .

Staying present helps you to be proactive in your thinking and anticipate what might happen, such as bringing extra lubricant for a catheterization or extra gloves for a dressing change.

By staying present, you are also better able to practice active listening. This raises your assessment skills and gives you more information as a basis for your interventions and decisions.

Use a Process

As you are developing critical thinking skills, it can be helpful to use a process. For example:

- Ask questions.

- Gather information.

- Implement a strategy.

- Evaluate the results.

- Consider another point of view.

These are the fundamental steps of the nursing process (assess, diagnose, plan, implement, evaluate). The last step will help you overcome one of the common problems of critical thinking in nursing — personal bias.

Common Critical Thinking Pitfalls in Nursing

Your brain uses a set of processes to make inferences about what’s happening around you. In some cases, your unreliable biases can lead you down the wrong path. McGowan places personal biases at the top of his list of common pitfalls to critical thinking in nursing.

“We all form biases based on our own experiences. However, nurses have to learn to separate their own biases from each patient encounter to avoid making false assumptions that may interfere with their care,” he says. Successful critical thinkers accept they have personal biases and learn to look out for them. Awareness of your biases is the first step to understanding if your personal bias is contributing to the wrong decision.

New nurses may be overwhelmed by the transition from academics to clinical practice, leading to a task-oriented mindset and a common new nurse mistake ; this conflicts with critical thinking skills.

“Consider a patient whose blood pressure is low but who also needs to take a blood pressure medication at a scheduled time. A task-oriented nurse may provide the medication without regard for the patient’s blood pressure because medication administration is a task that must be completed,” Slaughter says. “A nurse employing critical thinking skills would address the low blood pressure, review the patient’s blood pressure history and trends, and potentially call the physician to discuss whether medication should be withheld.”

Fear and pride may also stand in the way of developing critical thinking skills. Your belief system and worldview provide comfort and guidance, but this can impede your judgment when you are faced with an individual whose belief system or cultural practices are not the same as yours. Fear or pride may prevent you from pursuing a line of questioning that would benefit the patient. Nurses with strong critical thinking skills exhibit:

- Learn from their mistakes and the mistakes of other nurses

- Look forward to integrating changes that improve patient care

- Treat each patient interaction as a part of a whole

- Evaluate new events based on past knowledge and adjust decision-making as needed

- Solve problems with their colleagues

- Are self-confident

- Acknowledge biases and seek to ensure these do not impact patient care

An Essential Skill for All Nurses

Critical thinking in nursing protects patient health and contributes to professional development and career advancement. Administrative and clinical nursing leaders are required to have strong critical thinking skills to be successful in their positions.

By using the strategies in this guide during your daily life and in your nursing role, you can intentionally improve your critical thinking abilities and be rewarded with better patient outcomes and potential career advancement.

Frequently Asked Questions About Critical Thinking in Nursing

How are critical thinking skills utilized in nursing practice.

Nursing practice utilizes critical thinking skills to provide the best care for patients. Often, the patient’s cause of pain or health issue is not immediately clear. Nursing professionals need to use their knowledge to determine what might be causing distress, collect vital information, and make quick decisions on how best to handle the situation.

How does nursing school develop critical thinking skills?

Nursing school gives students the knowledge professional nurses use to make important healthcare decisions for their patients. Students learn about diseases, anatomy, and physiology, and how to improve the patient’s overall well-being. Learners also participate in supervised clinical experiences, where they practice using their critical thinking skills to make decisions in professional settings.

Do only nurse managers use critical thinking?

Nurse managers certainly use critical thinking skills in their daily duties. But when working in a health setting, anyone giving care to patients uses their critical thinking skills. Everyone — including licensed practical nurses, registered nurses, and advanced nurse practitioners —needs to flex their critical thinking skills to make potentially life-saving decisions.

Meet Our Contributors

Crystal Slaughter is a core faculty member in Walden University’s RN-to-BSN program. She has worked as an advanced practice registered nurse with an intensivist/pulmonary service to provide care to hospitalized ICU patients and in inpatient palliative care. Slaughter’s clinical interests lie in nursing education and evidence-based practice initiatives to promote improving patient care.

Jenna Liphart Rhoads is a nurse educator and freelance author and editor. She earned a BSN from Saint Francis Medical Center College of Nursing and an MS in nursing education from Northern Illinois University. Rhoads earned a Ph.D. in education with a concentration in nursing education from Capella University where she researched the moderation effects of emotional intelligence on the relationship of stress and GPA in military veteran nursing students. Her clinical background includes surgical-trauma adult critical care, interventional radiology procedures, and conscious sedation in adult and pediatric populations.

Nicholas McGowan is a critical care nurse with 10 years of experience in cardiovascular, surgical intensive care, and neurological trauma nursing. McGowan also has a background in education, leadership, and public speaking. He is an online learner who builds on his foundation of critical care nursing, which he uses directly at the bedside where he still practices. In addition, McGowan hosts an online course at Critical Care Academy where he helps nurses achieve critical care (CCRN) certification.

Effective clinical learning for nursing students

Approaches that meet student and nurse needs..

- Direct care nurses serve as significant teachers and role models for nursing students in the clinical setting.

- Building critical thinking skills is one of the most important outcomes in the clinical setting for nursing students.

- Collaboration with nursing faculty during the clinical rotation can ease the burden on direct care nurses and facilitate a positive learning experience for the student.

The nursing profession continues to experience several challenges—some longstanding and exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. The shortage of nurses at the bedside and reports of nurses planning to leave the profession soon place stress on the workforce and the healthcare system. The situation has put even more pressure on nursing schools to recruit and retain students who enter the workforce well-prepared for practice and capable of filling these vacancies. However, concerns exist surrounding students’ critical thinking skills and their readiness for a demanding career.

The challenge

A longstanding shortage of nursing school faculty and a reliance on new graduate nurses to serve as preceptors create challenges to properly preparing nursing students for a demanding role that requires excellent critical thinking skills.

What-Why-How? Improving Clinical Judgement

New nurses and clinical judgment

Nurse faculty shortage

Lack of interest and incentives lead to difficulty recruiting nurses from the bedside or practice to education. Many 4-year schools require a terminal degree to teach full-time in their undergraduate programs, but only 1% of nurses hold a PhD. In addition, according to the National Advisory Council on Nurse Education and Practice (NACNEP), the average doctorally prepared nurse faculty member is in their 50s, which means they may soon retire. The surge in doctor of nursing practice programs has helped to bridge this gap, but attracting advanced practice nurses to academia from their more lucrative practice roles continues to prove difficult.

Concerns about the practice readiness of new graduate nurses have existed for several years. Missed clinical experiences and virtual learning during the COVID-19 pandemic heightened those concerns. The National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) addressed the calls from nurse employers to make progress in this area by revamping the NCLEX-RN and NCLEX-PN exams to create Next Generation NCLEX (NGN), which includes more clinical judgment and critical thinking items. Nurse educators are working hard to prepare students for both practice and the new exam items by incorporating more active learning into classroom, clinical, and lab activities and emphasizing the importance of clinical judgment skills.

In most areas of the country, clinical student experiences have returned to pre-pandemic arrangements. State boards of nursing mandate maximum faculty-to-student ratios for clinical experiences. Schools can choose to have faculty supervise fewer students than the maximum, but faculty and clinical site shortages may eliminate that option. In many cases, preceptor-style experiences (such as capstone or practicum courses) have higher faculty-to-student ratios, and preceptors may have to meet specific criteria, such as a certain amount of experience.

Nursing faculty who facilitate on-site learning and supervise and teach students during their clinical experiences face several challenges. Some faculty supervise students across multiple units because unit size can’t accommodate 8 to 10 students at one time. Faculty may or may not have access to the organization’s electronic health records or other healthcare information technology, such as medication dispensing cabinets or glucometers.

In such instances, direct care nurses play an important role in the student’s experience at the clinical site. Their familiarity with the unit, the patient population, and the organization’s technology facilitates learning.

Direct care nurses

Allowing nursing students into the hospital can improve the patient care experience and potentially recruit students to work at the organization in the future. However, precepting a student or new employee creates an extra burden on an already overextended bedside nurse. NACNEP identifies several challenges for obtaining qualified preceptors, including lack of incentives and limited preparation in clinical teaching and learning strategies. Many hospitals have nursing students on the same unit several days a week to accommodate multiple area schools. This means that staff nurses are expected to teach students on most of their workdays during a typical school semester.

Unit nurse experience creates another barrier to effective precepting of nursing students. A study by Thayer and colleagues reported that the median length of experience for inpatient nurses working a 12-hour shift was less than 3 years at an organization. Without a better alternative, new graduate nurses frequently teach nursing students, although they may still be in what Benner describes as the advanced beginner stage of their career (still learning how to organize care, prioritize, and make clinical judgments). It’s difficult for someone who’s still learning and experiencing situations for the first time to teach complex concepts.

A guide to effective clinical site teaching

The following strategies promote critical thinking in students and collaboration with nurse faculty to ease direct care nurses’ teaching workload. Not every strategy is appropriate for all student clinical experiences. Consider them as multiple potential approaches to help facilitate meaningful learning opportunities.

Set the tone

Nursing students frequently feel anxious about clinical experiences, especially if they’ve been told or perceive that they’re a burden or unwanted on the unit. When meeting the student for the first time, welcome them and communicate willingness to have them on the unit.

If you feel that you can’t take on a student for the day, speak to the nurse faculty member and charge nurse to explore other arrangements. Nurse faculty recognize that work or personal concerns may require you to decline precepting a student. Faculty members want to find the best situation for everyone. If the charge nurse or supervisor determines that the student still needs to work with you, talk to the nurse faculty about how they can help ease the burden and facilitate the student’s learning experience for the day.

Begin your time with the student by asking about their experience level and any objectives for the day. Understanding what the student can or can’t do will help you make the most out of the clinical experience. You’ll want to know the content they’re learning in class and connect them with a patient who brings those concepts to life. A student may have assignments to complete, but their focus should be on patient care. Help the student identify the busiest parts of the day and the best time to review the electronic health record and complete assignments.

If a situation requires your full attention and limits training opportunities, briefly explain to the student what will happen. If you have time, provide the student with tasks or specific objectives to note during the observation. Involve the nursing faculty member to help facilitate the learning experience and make it meaningful.

Be a professional role model

Students like to hear about the benefits and rewards of being a nurse, and about each nurse’s unique path. Students also enjoy learning about the “real world” from nurses, but keep in mind that they’re impressionable. Speaking negatively about the unit, patients, organization, or profession may discourage the student. If you must deviate from standard care, such as performing a skill differently than it’s traditionally taught in school, provide the rationale or hospital policy behind the decision.

Feel free to discuss the student’s nursing school experience but don’t diminish the value of their education or assigned work. Keep in mind that school assignments, such as nursing care plans or concept maps, aren’t taught for job training but to deliberately and systematically promote critical thinking. These assignments allow a student to reflect on how a patient’s pathophysiology and nursing assessment and interventions relate to one another.

Reinforce how concepts students learn in school provide valuable knowledge in various settings. For example, if the student is on a medical-surgical unit but says that they want to work in obstetrics, engage the student by pointing out links between the two areas, such as managing diabetes and coagulation disorders. Provide encouragement and excitement about the student’s interest in joining the profession at a time of great need.

Build assessment skills

Explain to students your approach to performing assessments and organizing patient care. Most students learn comprehensive head-to-toe assessments but, in the clinical setting, need to focus on the most relevant assessments. To promote critical thinking, ask the student what data they should focus on gathering based on the patient’s condition. Many students focus on the psychomotor aspect of assessment (performing the assessment correctly); ask them about the subjective data they should gather.

Allow the student to perform an assessment and then compare findings. For example, a student may know that a patient’s lung sounds are abnormal but not remember what the sound is called or what it means. Provide them with the correct terminology to help connect the dots. Discuss with the student when reassessments are warranted. If appropriate, allow a student to reassess the patient (vital signs, output, pain, other physical findings) and then confirm their findings and discuss what any changes mean for the clinical situation. If you don’t have time for these types of discussions following a student’s patient assessment, ask nursing faculty to observe and discuss findings with the student.

Discuss care management

Take advantage of opportunities to discuss concepts such as prioritization, advocacy, delegation, collaboration, discharge planning, and other ways in which the nurse acts as a care manager. Pointing out what’s appropriate to delegate to unlicensed assistive personnel or a licensed practical nurse will prove valuable and help reinforce concepts frequently covered on the NGN exam.

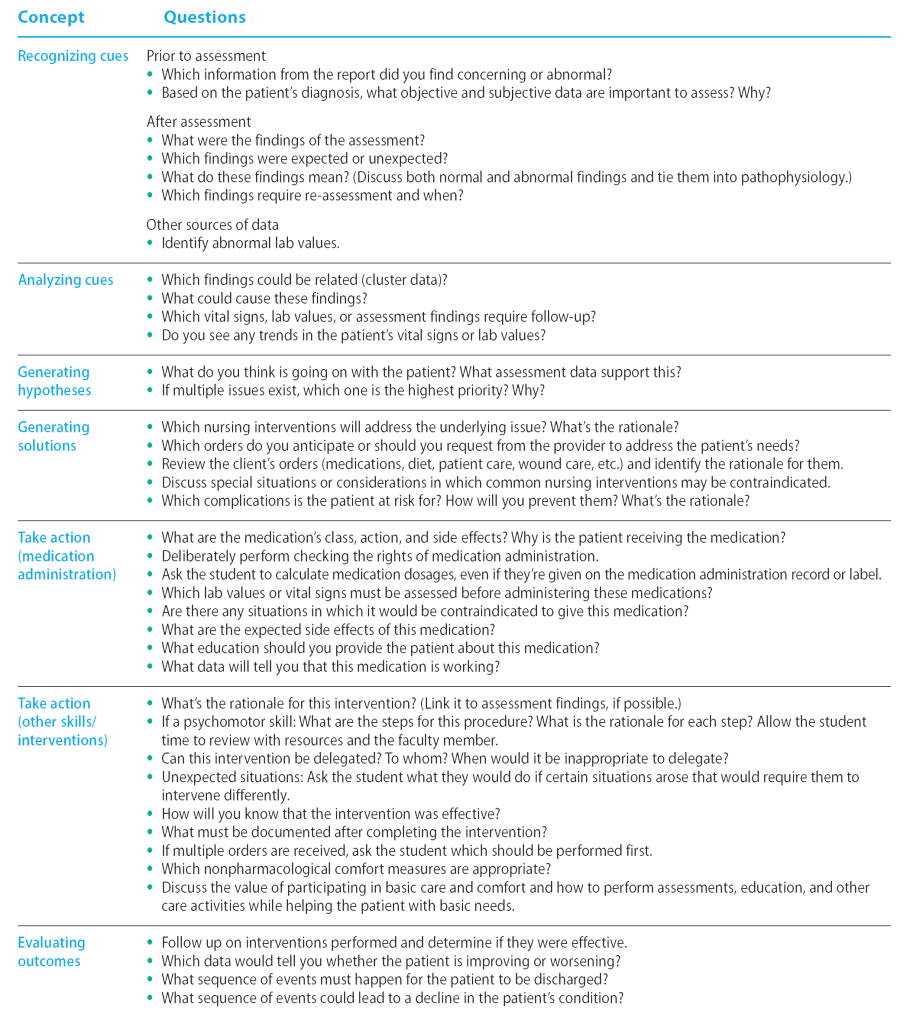

Promote critical thinking

The NCBSN has introduced the Clinical Judgment Measurement Model (CJMM) as a framework for evaluating the NGN exam, which incorporates unfolding case studies that systematically address six steps: recognize cues, analyze cues, generate hypotheses, generate solutions, take action, and evaluate outcomes. Each candidate encounters three case studies, with six questions, one for each step of the CJMM. Nursing faculty incorporate this framework and language into the nursing curriculum to help students think systematically and critically and prepare them for the exam.

Nurses with practice experience use this type of framework to gather information, make judgments, and take action. As a nurse approaches Benner’s competent stage of nursing practice, this type of thinking becomes intuitive, and nurses may not even be aware of the conclusions they draw and decisions they make based on their clinical judgment skills. To help students understand why something is happening, they should continue to work through a process like this deliberately. For example, many students view medication administration as a simple task and may say in post-conference discussion, “All I did was give meds.” You perform many assessments and make various judgments while administering medications, but you may not think to discuss them with students. Asking questions of students while they’re performing what may seem like repetitive tasks can help prompt critical thinking. (See Critical questions .)

Critical questions

Enhance self-efficacy

Many nurses believe that the student must follow them to every patient. This can be overwhelming for the direct care nurse and a barrier to agreeing to work with students. Other approaches can better facilitate learning. Most students will complete an assignment focused on one or two patients. Encourage the student to spend time alone with those patients to perform a more comprehensive history and assessment, help patients with basic care, and provide education. Select a patient who might enjoy the extra attention to ensure a mutually beneficial experience.

Also, consider asking the student to find information using available resources. Such inquiry can benefit you and the student. For example, prompt a student to answer one or more critical thinking questions using their textbooks or resources available on the hospital’s intranet. If time prevents you from explaining complex topics or helping the student problem-solve, ask the student to take the information they find to their faculty member to review. Nurse faculty won’t be familiar with the specific details of all patients on the unit, so identify the most appropriate questions for the student to consider to help the nurse faculty facilitate learning.

Allowing the student time to find answers themselves builds self-efficacy and confidence and also relieves some of the stress and anxiety associated with being asked questions on the spot. This strategy also models the professional approach of using evidence-based resources to find information as needed in the clinical setting.

To ensure a positive learning experience and reduce anxiety, provide the student with ample time to prepare for performance-based skills. For example, identify an approximate time that medications will be administered to one patient and ask the student to independently look up the medication information by that time. This is more beneficial for the student than observing every patient’s medication administration or participating only in psychomotor tasks, such as scanning and giving injections. This also can free up your time by setting the expectation that the student will have the chance to prepare for and be directly involved in one medication pass.

Similarly, if an opportunity exists for practicing a psychomotor skill, such as inserting a urinary catheter or suctioning a tracheostomy, ask the student to review the procedure with their instructor using hospital policy and resources. If time doesn’t allow for a review, have the student observe to ensure provision of the best care and efficient use of time and resources.

Opportunities in education

Nurses who enjoy working with students or new staff members may want to consider academic roles. Many advanced nursing degrees, available in various formats, focus on education. For those who want to try teaching or have an interest in teaching only in the clinical setting, opportunities exist to work as adjunct faculty or to participate in hospital-based professional development activities. Adjunct faculty (part-time instructors) teach a variety of assignments and workloads, including in clinical, lab, or classroom settings. Many clinical adjunct faculty are nurses who also work in the organization with patients and may teach one group of students one day a week. Clinical and lab assignments vary from 4- or 6-hour experiences to 12-hour shifts.

According to NACNEP, most nursing programs require that adjunct faculty and clinical preceptors have the same or higher level of educational preparation as the program; for example, a nurse with a bachelor of science in nursing (BSN) may be able to teach clinicals for associate degree in nursing or BSN programs, depending on the state’s requirements and the school’s needs. Educational requirements to work in nursing programs vary by school. In some cases, adjunct faculty who don’t have a master’s degree may be supervised by full-time faculty with advanced degrees.

Benefits for adjunct faculty can include extra income, professional development, personal reward, tuition discounts or remissions, and giving back to the profession. Locate opportunities on nursing school websites or by talking to the nursing instructors or administrators in the local area.

Everyone benefits

Applying teaching approaches that benefit students and nurses can help ensure a positive clinical learning experience for everyone. When you graciously accept and teach students you help create positive encounters that enhance student critical thinking skill development, aid program retention, and support organizational recruitment.

Jennifer Miller is an assistant professor of nursing at the University of Louisville School of Nursing in Louisville, Kentucky .

American Nurse Journal. 2024; 19(4). Doi: 10.51256/ANJ042432

American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Nursing faculty shortage fact sheet. October 2022. aacnnursing.org/news-information/fact-sheets/nursing-faculty-shortage

Benner P. From Novice to Expert: Excellence and Power in Clinical Nursing Practice . Menlo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley; 1984.

National Advisory Council on Nurse Education and Practice. Preparing nurse faculty, and addressing the shortage of nurse faculty and clinical preceptors. January 2021. hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hrsa/advisory-committees/nursing/reports/nacnep-17report-2021.pdf

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. Clinical Judgment Measurement Model. 2023. nclex.com/clinical-judgment-measurement-model.page

Thayer J, Zillmer J, Sandberg N, Miller AR, Nagel P, MacGibbon A. ‘The new nurse’ is the new normal. June 2, 2022. Epic Research. epicresearch.org/articles/the-new-nurse-is-the-new-normal

Key words: nursing students, nursing education, critical thinking, precepting

Let Us Know What You Think

1 comment . leave new.

All nursing programs need to put in more clinical time. Students do not get the time in clinicals so they do not have the opportunities to develop their clinical judgement and thinking skills. Clinical time is what glues concept and theory together if they don’t get the clinical time they are less likely to develop these skills which contributes to errors, burnout and nurses leaving the field.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

NurseLine Newsletter

- First Name *

- Last Name *

- Hidden Referrer

*By submitting your e-mail, you are opting in to receiving information from Healthcom Media and Affiliates. The details, including your email address/mobile number, may be used to keep you informed about future products and services.

Test Your Knowledge

Recent posts.

Built to fit

ANA Enterprise News, October 2024

Responding to workplace violence

Answering the call

Creating an organization for future generations

Firearm safety: Nurses’ knowledge and comfort

The Secret Garden: A staff-only wellness and respite space

Healthy Nurse, Healthy Nation: 2024 Highlights Report

Nurses build coalitions at the Capitol

Stop fall prevention practices that aren’t working

Self-compassion in practice

Mitigating patient identification threats

Reflections: My first year as a Magnet® Program Director

Collective wisdom

The role of hospital-based nurse scientists

Miller J. Effective clinical learning for nursing students. American Nurse Journal. 2024;19(4):32-37. doi:10.51256/anj042432 https://www.myamericannurse.com/effective-clinical-learning-for-nursing-students/

#1 Duquesne University Graduate School of Nursing is Ranked #1 for Veterans by Militaryfriendly.com for 7 years running

- Adult-Gerontology Acute Care Nurse Practitioner

- Executive Nurse Leadership and Health Care Management

- Family Nurse Practitioner

- Forensic Nursing

- Nursing Education and Faculty Role

- Psychiatric-Mental Health Nurse Practitioner

- Clinical Leadership

- Admissions & Aid

- About Duquesne

- Why Duquesne Online?

Developing Critical-Thinking Skills in Student Nurses

April 8, 2020

View all blog posts under Articles | View all blog posts under Master of Science in Nursing

Critical thinking skills for nurses include problem-solving and the ability to evaluate situations and make recommendations. Done correctly, critical thinking results in positive patient outcomes, Srinidhi Lakhanigam, an RN-BSN, said in a Minority Nurse article.

“Critical thinking is the result of a combination of innate curiosity; a strong foundation of theoretical knowledge of human anatomy and physiology, disease processes, and normal and abnormal lab values; and an orientation for thinking on your feet,” Lakhanigam said in “Critical Thinking: A Vital Trait for Nurses.” “Combining this with a strong passion for patient care will produce positive patient outcomes. The critical thinking nurse has an open mind and draws heavily upon evidence-based research and past clinical experiences to solve patient problems.”

Since the 1980s, critical thinking has become a widely discussed component of nurse education, and a significant factor for National League for Nursing (NLN) nursing school accreditation. Nursing school curriculum is expected to teach students how to analyze situations and develop solutions based on high-order thinking skills. For nurse educators who are responsible for undergraduate and graduate learners , teaching critical thinking skills is crucial to the future of healthcare.

Characteristics of Critical Thinkers

A landmark 1990 study found critical thinkers demonstrate similar characteristics. The Delphi Report by the American Philosophical Association (APA) identified these cognitive skills common to critical thinkers:

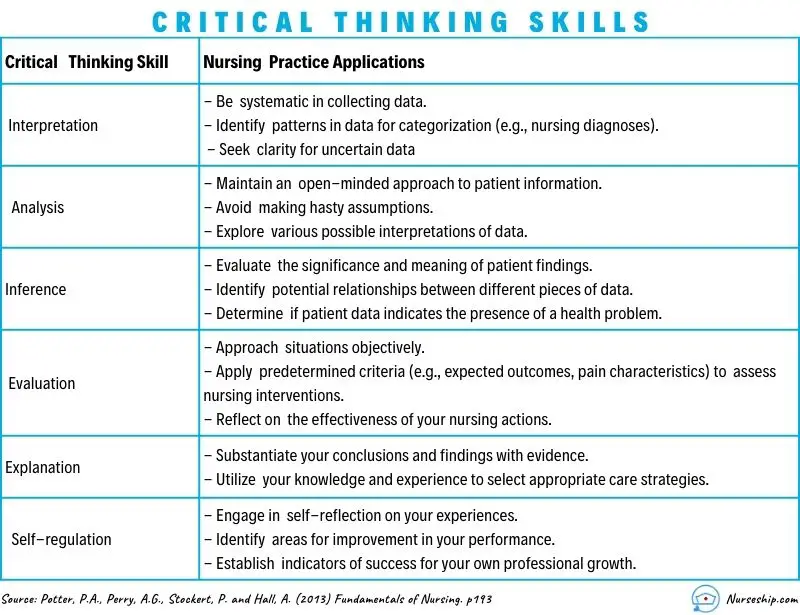

Interpretation

Critical thinkers are able to categorize and decode the significance and meaning of experiences, situations, data, events, and rules, among others.

Critical thinkers can examine varying ideas, statements, questions, descriptions and concepts and analyze the reasoning.

Critical thinkers consider relevant information from evidence to draw conclusions.

Explanation

Critical thinkers state the results of their reasoning through sound arguments.

Self-regulation

Critical thinkers monitor their cognitive abilities to reflect on their motivations and correct their mistakes.

In addition, critical thinkers are well-informed and concerned about a wide variety of topics. They are flexible to alternative ideas and opinions and are honest when facing personal biases. They have a willingness to reconsider their views when change is warranted.

In nursing, critical thinking and clinical reasoning are inextricably linked, columnist Margaret McCartney said in the BMJ . While experienced nurses are able to make sound clinical judgements quickly and accurately, novice nurses find the process more difficult, McCartney said in “Nurses must be allowed to exercise professional judgment.”

“Therefore, education must begin at the undergraduate level to develop students’ critical thinking and clinical reasoning skills,” McCartney said. “Clinical reasoning is a learnt skill requiring determination and active engagement in deliberate practice design to improve performance. In order to acquire such skills, students need to develop critical thinking ability, as well as an understanding of how judgments and decisions are reached in complex healthcare environments.”

Teaching Critical Thinking to Nurses

In 2015, a study in the Journal of College Teaching & Learning found a positive correlation between critical thinking skills and success in nursing school. The study said, “It is the responsibility of nurse educators to ensure that nursing graduates have developed the critical thinking abilities necessary to practice the profession of nursing.”

To help new nurses develop critical-thinking skills, the professional development resources provider Lippincott Solutions recommended nurse educators focus on the following in the classroom:

Promoting interactions

Collaboration and learning in group settings help nursing students achieve a greater understanding of the content.

Asking open-ended questions

Open-ended questions encourage students to think about possible answers and respond without fear of giving a “wrong” answer.

Providing time for students to reflect on questions

Student nurses should be encouraged to deliberate and ponder questions and possible responses and understand that perhaps the immediate answer is not always the best answer.

Teaching for skills to transfer

Educators should provide opportunities for student nurses to see how their skills can apply to various situations and experiences.

In the Minority Nurse article, Lakhanigam also said students who thirst for knowledge and understanding make the best critical thinkers. The author said novice nurses who are open to constructive criticism can learn valuable lessons that will translate into successful practice.

At the same time, however, critical thinking skills alone will not ensure success in the profession , Lakhanigam said in the article. Other factors count as well.

“A combination of open-mindedness, a solid foundational knowledge of disease processes, and continuous learning, coupled with a compassionate heart and great clinical preceptors, can ensure that every new nurse will be a critical thinker positively affecting outcomes at the bedside,” Lakhanigam said.

Another element that ensures success as both an educator and student is earning a nursing degree from a school that focuses on student accomplishments. At Duquesne University’s School of Nursing, students learn best practices in healthcare. The online master’s in nursing program prepares educators to train the next generation of nurses.

About Duquesne University’s online Master of Science in Nursing (MSN) Program

Duquesne University’s MSN curriculum for the Nursing Education and Faculty Role program focuses on preparing registered nurses (RNs) for careers as nurse educators. Students enrolled in the online master’s in nursing program learn the skills needed in the classroom and for clinical training. RNs learn how to empower student nurses to work to their fullest potential.

The MSN program is presented entirely online, so RNs can pursue their career goals and continue personal responsibilities simultaneously. Duquesne University has been recognized for excellence in education as a U.S. News & World Report Best Online Graduate Nursing Program and best among Roman Catholic universities in the nation.

For more information, contact Duquesne University today.

Critical Thinking: A Vital Trait for Nurses: Minority Nurse

Consensus Descriptions of Core CT Skills And Sub-Skills: Delphi

Margaret McCartney: Nurses must be allowed to exercise professional judgment: BMJ

Predicting Success in Nursing Programs: Journal of College Teaching & Learning

Turning New Nurses Into Critical Thinkers: Wolters Kluwer

- Study Protocol

- Open access

- Published: 14 October 2024

Exploring a learning model for knowledge integration and the development of critical thinking among nursing students with previous learning: a qualitative study protocol

- Chun-Chih Lin ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7548-7720 1 , 2 ,

- Chin-Yen Han ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7464-7507 2 , 3 ,

- Ya-Ling Huang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6156-4721 4 , 5 ,

- Han-Chang Ku ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9371-0607 1 &

- Li-Chin Chen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5724-2946 2

BMC Medical Education volume 24 , Article number: 1140 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

291 Accesses

Metrics details

Students often struggle to apply their knowledge of bioscience to their care practice. Such knowledge is generally learned through remembering and understanding, but retention quickly fades. They also experience difficulty progressing to higher-order cognitive skills such as applying, analyzing, evaluating, and even creating, which are necessary to develop soft skills, such as critical thinking, in the care profession. In order to improve existing programs, there is a need to better understand students' prior learning experiences and processes. The proposed study will explore the previous learning experiences of nurses enrolled in a two-year nursing program at a Taiwan university and identify the challenges they face in integrating multidisciplinary knowledge and developing critical thinking competency. The study will adopt a constructivist grounded theory methodology to collect interview data. The findings are expected to improve higher cognitive learning performance and inform the revision of the two-year nursing curriculum.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

In nursing education, theoretical knowledge focuses on human body systems and is primarily or often imparted through lectures. This mode of teaching–learning results in a separation between theoretical knowledge and clinical practice. As a result, it is difficult for students to connect these two domains, and they often struggle to integrate these two types of knowledge in a care scenario. Nursing curricula aimed at basic medicine and applying it to nursing care learning. For instance, knowledge of biosciences such as physiology or pharmacology is not repeated in courses like Adult Nursing. In Bloom’s cognition hierarchy of learning [ 1 ], learning outcomes are primarily set in relation to remembering and understanding rather than higher-order outcomes such as applying or analyzing. Since knowledge retention fades over time [ 2 ], students may be unable to adequately apply academic knowledge when faced with complex health issues in individual cases.

In technical and vocational education in nursing, the curricula’s learning outcomes are based on three types of objectives—cognitive, affective, and skills-based—equivalent to remembering, learning attitude, and techniques in Bloom’s taxonomy [ 3 ]. If learning continues with constant practice, it is possible to achieve learning outcomes at a proficiency level. However, the acquired knowledge may gradually fade if learning is not continued. This could result in missed opportunities to achieve higher-order cognitive learning, such as the ability to analyze or create [ 2 ]. Additionally, prior knowledge may be difficult to internalize, and unfamiliar skills may become challenging to acquire.

The educational goals of the technical and vocational systems are likely to play a role in determining whether learning continues after graduation. Nursing students in junior college are expected to pass a national qualification examination and enter the workplace immediately afterward, meaning their cognitive, affective, and skills learning will continue to develop. They will advance to a higher level of learning performance. However, students who pursue a higher degree may lack extrinsic learning motivation, and these abilities may stagnate or regress. Continuing nursing education programs such as 2-year programs can improve students’ extrinsic learning motivation and transform it into intrinsic learning motivation, which leads to improved internalization and integration of knowledge and enhanced critical thinking skills [ 4 , 5 ]. A better understanding of students' prior learning experiences and processes is necessary to make appropriate revisions to the curriculum.

Memorization and understanding of learning concepts are essential for accumulating knowledge. However, merely holding onto this knowledge can weaken nursing graduates' critical thinking and problem-solving abilities [ 6 ]. While nursing graduates with associate degrees possess strong theoretical understanding, they are often unable to apply this knowledge to a holistic consideration of the circumstances of individual patients, relying instead on managing their patients' symptoms and practitioners' prescriptions. The consequences are less effective patient care and a devaluation of nursing professionalism.

In summary, nursing students are limited in their theoretical knowledge and critical thinking development, which hinders their ability to perform comprehensive evaluations of patients and make effective clinical care decisions. This gap between learning and practice could be addressed through further education that equips students to integrate and apply multidisciplinary knowledge to the practical care domain. To this end, the proposed study seeks to identify the factors that affect how students integrate academic knowledge to improve critical thinking and overall learning satisfaction, as Chang et al. [ 7 ] recommended. Such information is needed to inform the revision of the two-year nursing program curriculum.

Literature review

Learning models and knowledge integration.

The ability to synthesize knowledge is fundamental in all health professions, including nursing [ 8 ]. Competent nurses require theoretical knowledge of biosciences and care practice to make complex patient management decisions. Quality care depends on nurses’ ability to combine clinical reasoning (critical thinking) with accurate health information in real-time situations. Nursing education should aim to bridge the gap between theoretical concepts learned in classrooms and their practical application in clinical settings [ 9 ].

Nursing education fosters the development of complex knowledge and soft skills, known as core nursing values or competencies [ 10 ]. A scoping review conducted by Widad and Abdellah [ 11 ] identified various soft skills that should be included in the nursing curriculum and concluded that different teaching and learning strategies were required to enhance these skills. Other researchers have emphasized the centrality of effective learning with a learner-centered approach that encourages active participation in learning and an interdisciplinary model for integrative learning [ 12 ].

To date, a number of innovative teaching methods have been found to improve learning effectiveness. Kou [ 13 ] proposed a reward-learning model that focuses on how extrinsic rewards motivate individuals to engage in knowledge-acquisition behavior, noting that learning involves explaining and strengthening one's information-seeking behavior. Collaborative learning has improved cognitive integration or combining knowledge from multiple disciplines [ 8 ]. Challenge-based learning is a collaborative approach that encourages students to engage in multidisciplinary learning and take action to solve challenges [ 14 ]. Problem-based learning (PBL) has been shown to enhance students' critical thinking and self-directed learning for long-term knowledge retention [ 15 ]. For instance, Gao et al. [ 16 ] reported that an approach that combined mind mapping with PBL improved undergraduate nursing students' theoretical knowledge, practical abilities, and self-learning skills. In contrast, Manuaba et al. [ 17 ] concluded from their study that the PBL approach did not appear to improve critical thinking and problem-solving skills compared to the conventional teaching method. Another model, inquiry-based learning (IBL), has been identified as equipping students with the ability to investigate and solve problems [ 18 ]. Finally, a flipped classroom teaching model has been proposed as an effective way of supporting students to develop high-level cognitive skills [ 19 ], develop their critical thinking [ 20 ], and improve their motivation and interactions. The flipped classroom teaching model is a form of blended learning that centers around students and reverses their learning activities in groups while in class.

Critical thinking in nursing

According to Benner [ 21 ], the traditional classroom approach to teaching and learning theoretical knowledge needs to be transformed into one that focuses on cultivating learners' critical thinking and clinical judgment abilities to bridge the gap between theoretical knowledge and clinical practice. Similarly, Gonzalez et al. [ 22 ] argue that understanding the connection between learned knowledge and the clinical situation is crucial for developing critical thinking skills. Such understanding allows the learner to apply clinical decision-making abilities to the care situation. In other words, learners must integrate their knowledge, critical thinking, clinical reasoning, and clinical judgment skills into clinical practice. This learning method draws on various disciplines to help learners develop logical and critical thinking skills while eliminating the monotony of academic learning.

Critical thinking refers to the cognitive process of exploring existing information and analyzing available information to assist in judgment and decision-making. In simpler terms, critical thinking involves an individual's use of logical thinking to regulate their thoughts. As such critical thinking involves several skills, such as interpretation, reasoning, evaluation, self-regulation, analysis, and inductive and deductive logical reasoning [ 23 ]. The process enables individuals to thoughtfully consider information from the real world, construct questions, and bridge the gap between theory and practice. Demonstrating critical thinking skills is a significant component of professional practice in nursing [ 24 ]. Nursing can be regarded as a cognitive process in which critical thinking is necessary to gather information, make clinical decisions, and solve complex and diverse clinical health problems in individual cases. Accordingly, critical thinking is essential to developing care competencies at every stage of the nursing process. Consequently, reasoning or critical thinking has become a central component of nursing education [ 25 ].

There is a close relationship between critical thinking and deductive and inductive logic. Deductive and inductive reasoning are two distinct forms of logical thinking. Deductive reasoning starts from general concepts and reasons toward specific conclusions, whereas inductive reasoning draws conclusions from specific observations and infers general principles. Both types of reasoning play a crucial role in critical thinking [ 26 ], but their processes and outcomes differ. In the classroom, deductive logic learning explains the theoretical principles of the course content and demonstrates their application to situations. This kind of learning helps students acquire theoretical knowledge and connects various concepts to form a series of logical theoretical understandings. Concept mapping is an example of this approach. Inductive logic learning, on the other hand, can help students develop a deeper understanding of the concepts, which enables them to think more critically about what they have learned. This results in more comprehensive and long-lasting knowledge that is not based merely on memorization, which can have a negative effect on problem-solving skills. Therefore, incorporating deductive and inductive logic strategies in teaching can enhance learners' conceptual understanding and problem-solving abilities [ 27 ].

Critical thinking is usually associated with logical thinking, problem-solving, and critical reflection [ 28 ].Although these abilities are all related to building convincing arguments and enhancing thinking skills, they have important differences. Critical thinking focuses on uncovering the essence of things, with an emphasis on achieving a comprehensive understanding at the cognitive level. It is characterized by carefully collecting relevant information and objectively evaluating a phenomenon or state. It involves exploring and reconsidering the problem to avoid subjective biases and seek the most accurate factual situation. It seeks to present diverse views and positions on events, emphasizing logical and rational judgment. In contrast, critical reflection involves introspection and self-reflection. It emphasizes self-criticism and aims to identify right and wrong courses of action [ 29 ]. As a result, critical thinking is often considered an essential thinking skill for practice. Both reflection and critical thinking have been identified as essential nursing skills for appropriate patient care. Despite these conceptual and operational differences, critical thinking and reflection share many commonalities and can impact each other's development [ 30 ]. These include analysis, interpretation, evaluation, reasoning, information searching, logic, cognitive processes of reasoning, and knowledge translation, all of which are necessary for making well-considered clinical professional decisions. Clinical decision-making plays a crucial role in ensuring safe patient care, and critical thinking is a vital cognitive process for clinical decision-making. Accordingly, critical thinking is vital in clinical nursing practice. However, there is a lack of clarity around the most effective teaching–learning methods to foster problem-solving and critical-thinking abilities in students [ 31 ].

In summary, continuous improvement in students’ inductive and deductive logical reasoning skills is necessary to cultivate higher-order cognitive skills, such as critical thinking. The application of critical thinking in professional disciplines involves the cognitive processes of academic application, analysis, evaluation, and creation. This conceptual process is vital for clinical decision-making and safe patient care. Among the various learning strategies that have been proposed to cultivate students' problem-solving and critical thinking, there is broad agreement that critical thinking awareness (awareness) and reflection ability (reflection) are important components [ 32 , 33 ].

Academic self-efficacy and knowledge integration

The proposed study employs the concept of learning self-efficacy, which has been used to indicate the effectiveness of learners’ ability to integrate theoretical knowledge. According to Bandura [ 34 ], self-efficacy refers to an individual’s belief in their ability to perform a task and achieve a goal. Four factors influence self-efficacy: mastery experience, vicarious experience, verbal persuasion, and psychological and affective states. Individuals confident in their abilities are more likely to persevere and work hard until they succeed, regardless of the task’s difficulty. As a result, self-efficacy beliefs are considered predictors, mediators, or moderators of task completion [ 35 , 36 ].

Learning self-efficacy refers to students’ belief in their ability to achieve their learning goals and demonstrate their effectiveness in learning. Those who possess high learning self-efficacy show positive motivation towards learning even when faced with difficulties, and they persist in their efforts to solve problems. On the other hand, when students with low learning self-efficacy encounter learning difficulties, they hesitate and lack the motivation to resolve the issues. Bulfone et al. [ 35 ] reported that most students’ learning self-efficacy remained relatively stable. However, those with increased learning self-efficacy demonstrated improved learning motivation and problem-solving skills. Previous research has used learning self-efficacy to predict learning motivation [ 37 ] and learning effectiveness [ 36 ]. The results indicated that higher learning self-efficacy was associated with stronger self-directed learning ability, more psychologically safe learning, and more positive learning results, demonstrating learning resilience. Basith et al. [ 36 ] found that academic achievement was positively related to learning self-efficacy; students with strong beliefs in their learning abilities were more likely to act to achieve their learning goals. As a result, they were more likely to pass examinations, improve their academic performance, and achieve their learning objectives. The findings also found that individuals with lower learning self-efficacy were more likely to experience emotional breakdown when faced with learning pressure. Gulley et al. [ 38 ] found a positive correlation between learning self-efficacy and performance on national licensure exams, indicating that students with high self-efficacy are more likely to learn effectively and successfully.

Overall. The research findings indicate that motivation, learning self-efficacy, and effectiveness are interdependent. Enhancing learners’ intrinsic motivation can increase learning achievement [ 39 ]. At the same time, learning self-efficacy has the potential to predict both learning motivation [ 37 ] and learning effectiveness [ 36 ]. The relationship between intrinsic motivation, learning self-efficacy, involvement, and effectiveness is mutually reinforcing. Each factor has an impact on the others. According to Dunn and Kennedy [ 37 ], there is a positive correlation between intrinsic motivation and self-efficacy, which, in turn, predicts students’ learning involvement. Moreover, learning involvement is an indicator of students’ learning achievement. Therefore, enhancing learning self-efficacy can foster learning motivation and effectiveness [ 36 ].

Aim and objectives

The proposed study aims to identify the factors that influence the integration of multidisciplinary knowledge and the development of critical thinking among undergraduate nursing students in two-year programs. The specific objectives are to (1) document the learning experience of undergraduate nursing students in their previous Junior Nursing College, (2) develop learning opportunities that effectively incorporate knowledge integration, and (3) identify learning needs for the development of critical thinking skills.

Study design

Charmaz’s constructivist grounded theory (CGT) [ 40 ] will underpin the study design. CGT is a method derived from traditional grounded theory that focuses on group experiences rather than individual experiences by focusing on understanding interactions, processes, and events. It aims to generate concepts and ideas based on a distinction between reality and truth. This means that researchers manage their constructions and interpretations of the participants’ constructions and interpretations, and the results are contextualized. The theoretical concepts of a constructivist approach serve as interpretive frameworks and offer an abstract understanding rather than a theory for explanation and prediction. Knowledge is, therefore, created and constructed during the research process. In the proposed study, therefore, CGT is considered an appropriate method for an inductive exploration and analysis of the complex learning process in the context of undergraduate nursing education.

CGT will explore nursing students’ previous learning experiences and the challenges affecting their ability to integrate multidisciplinary knowledge and critical thinking competency. The study design will be based on the five key elements in this methodology for developing lesson plans: (1) The theoretical framework will inform the sampling strategy. (2) Study participants will be able to provide rich information on the phenomenon under investigation. (3) Data collection and analysis will proceed simultaneously until saturation as a sufficient sample size is achieved [ 41 ]. (4) Data collection may be modified as theoretical insights emerge. (5) continuous data collection, analysis, and integration will occur. These five elements will be deployed to explore the nursing learning process and identify the factors influencing integrating multidisciplinary knowledge and critical thinking development.

Chang Gung University of Science and Technology has two northern and southern Taiwan campuses. The study will be conducted at both campuses, with a total student population 6,100. This includes 4,300 students undertaking four- and two-year nursing programs at the baccalaureate level. Both campuses have an annual enrolment of nearly 1,000 students in the two-year nursing program. This study will recruit participants from two-year nursing programs who completed their five-year study in nursing with a diploma degree obtained, already have a nursing license, and could practice in clinical settings. However, they all wish to study further to get a bachelor's degree.

A theoretical and purposive sampling strategy will be used to recruit participants for the study. To be eligible for the study, potential participants must meet the following criteria: (1) aged 18 years or older, (2) currently enrolled in the Evaluation and Analysis of Adult Nursing Cases course, and (3) be willing to participate in face-to-face interviews that will be audio-recorded. Potential participants will be excluded if they (1) withdraw from the Evaluation and Analysis of Adult Nursing Cases course, (2) have prior clinical nursing experience, and/or (3) have a non-nursing academic background in Junior Nursing College.

Data collection

The primary investigator (PI) will conduct all interviews. A semi-structured interview guide format will be used to ensure both consistency and flexibility in data collection. The interview guide will also maintain focus and avoid bias toward the researcher’s specific areas of interest. Interviewing in the participants’ and interviewers’ common language will maximize data quality. Sharing the same nursing background and language will facilitate an in-depth understanding and interpretation of verbal and non-verbal cues and maximize data quality. With participants’ permission, interviews will be audio-recorded to ensure accuracy. Participants will be encouraged to share their perspectives and experiences of previous academic studies.

Data management and analysis

The interviews will be transcribed verbatim. The transcripts and audio recordings will be coded under the same filename. The audio recordings will be listened to repeatedly to gain a deeper insight into the data, and the transcripts will be read line-by-line to obtain a sense of the text’s whole meaning. Constant comparative data analysis will be performed to focus interviews on the subsequent process of theoretical sampling to develop the properties of categories until theoretical satisfaction. All transcripts will be carefully read several times and systematically coded using open coding. They will then be read again, and any keywords or phrases relating to the issues under investigation will be captured in the participants’ own words. The PI will undertake preliminary data analysis, and the results will be discussed with the study team to obtain consensus on the emerging interpretation.

Study rigor

The quality of the study will be evaluated based on its credibility, originality, resonance, and usefulness [ 42 ]. Credibility is ensured by having the primary author conduct all interviews to maintain consistency and quality. Credibility will be enhanced through purposive and theoretical sampling, audit trail techniques, member checking, and thick and rich descriptions. The research team will meet frequently to reach a consensus on identifying codes and categories and the process of theoretical sampling. The originality of the findings will be demonstrated in the use of verbatim quotes in the report and continuous searching of the literature. Resonance will be achieved by identifying categories that provide in-depth insights, and interviews will be recorded and transcribed accurately to provide thick and rich data. Furthermore, a nursing educator will read data from the coding process and report on the study. The study’s usefulness will be evaluated as follows: sole interviewer, audit trail, and a better understanding of nursing students’ learning difficulties in integrating knowledge and developing critical thinking skills .

Ethical considerations

Once organizational permission to conduct the study has been obtained from the university, participants will be recruited via an invitation to the school email system. The email will explain the importance of the study and invite students to participate in face-to-face semi-structured individual interviews. Only the PI will conduct an open-ended and in-depth interview with individuals.

Potential participants will receive an invitation via the university's email system. Potential participants who demonstrate interest in participating will receive an information sheet and consent form and be given time to read and consider the information. The participants will be fully informed about the study, including its purpose, the procedures for data collection, potential risks and benefits, time commitment, and how their rights to privacy and anonymity will be protected. An opportunity to ask questions will be given before signing the consent form. Participants will be advised that participation is voluntary and have the right to withdraw from the study without penalty. The decision to participate or not will in no way impact their involvement in the course. No coercive or deceptive tactics will be used to encourage participation. The interviews will be conducted at a time and place of the participant’s choosing, but preferably in an independent, safe, and quiet location in the workplace. Before the interview commences, the interviewer will explain the interviewee’s rights in relation to their participation, answer any questions, and obtain written consent.

Participants will be assigned a number code. No names or other identifying information will be recorded on the audio records, transcripts, or field notes. No physical risk to the participants is anticipated. Some participants may experience psychological discomfort in reflecting on their experiences during interviews. The risk management plan includes continuous assessment of a participant’s level of comfort or anxiety through the interview, and interviews will be terminated and rescheduled if any discomfort or anxiety occurs. Participants will be referred to a free counseling service if this meets their needs. Participants will be informed that they can refuse to answer questions during the interview.

Interpretation

This study employs constructivist grounded theory to investigate how previous learning experiences and perspectives affect nursing students' knowledge integration and critical thinking development.

Limitations

Different universities in Taiwan may have varying criteria for selecting students for enrollment based on their academic achievements in the two-year nursing program entrance system. This study will only be conducted in a single university, based on the institution's goals of nursing student cultivation. Therefore, the findings may not apply to other institutions. Furthermore, the study saturation or theoretical saturation in qualitative studies may not be suitable for this study. Therefore, a sufficient sample size [ 41 ] will be used in the current study's data collection and analysis process.

The proposed study will investigate how students' learning experiences during their associate degree in nursing affect their ability to integrate knowledge and develop critical thinking skills. The two-year nursing degree serves as a lead for a bachelor's degree for students with a five-year nursing associate degree. Also, a bachelor's degree in nursing is becoming a standard educational qualification for clinical practice. Accordingly, it is important to ensure that the curriculum design in the two-year program is effective in cultivating students' development of these 'soft' skills to bridge the gap between nursing education systems.

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Bloom BS, Engelhart MD, Furst E J, Krathwohl DR. Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. 1956; David McKay

Molina-Torres G, Rodriguez-Arrasti M, Alarcón R, Sánchez-Labraca N, Sánchez-Joya M, Roman P, Requena M. Game-based learning outcomes among physiotherapy students: comparative study. JMIR Serious Games. 2021;9(1):e26007.

Article Google Scholar

Bloom BS. In: Anderson LW, Krathwohl DR, editors. A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: a revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives, complete ed. New York: Longman; 2001.

Google Scholar

Vu T, Magis-Weinberg L, Jansen BRJ, Atteveldt NV, Janssen TWT, Lee NC, Maask HLJ, Raijmakers MEJ, Sachisthal MSM, Meeter M. Motivation-Achievement Cycles in Learning: A Literature Review and Research Agenda. Educ Psychol Rev. 2022;34:39–71.

Walsh P, Owen PA, Mustaf N, Beech R. Learning and teaching approaches promoting resilience in student nurses: an integrated review of the literature. Nurse Educ Prac. 2020;45:102748.

Yeung MM, Yuen JW, Chen JM, Lam KK. The efficacy of team-based learning in developing the generic capability of problem-solving ability and critical thinking skills in nursing education: A systematic review. Nurse Educ Today. 2023;122:105704.

Chang CY, Kuo SY, Hwang GH. Chatbot-facilitated nursing education. Educ Technol Soc. 2022;25(1):15–27.

Ignacio J, Chen H-C. Cognitive integration in health professions education: Development and implementation of a collaborative learning workshop in an undergraduate nursing program. Nurse Educ Today. 2020;90:104436.

Culyer LM, Jatulis LL, Cannistraci P. Brownel CAEvidence-based teaching strategies that facilitate transfer of knowledge between theory and practice: what are nursing faculty using? Teach Learn Nurs. 2018;13(3):174–9.

Sancho-Cantus D, Cubero-Plazas L, BotellaNavas M, Castellano-Rioja E, Cañabate Ros M. Importance of Soft Skills in Health Sciences Students and Their Repercussion after the COVID-19 Epidemic: Scoping Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20:4901.

Widad A, Abdellah G. Strategies used to teach soft skills in undergraduate nursing education: a scoping review. J Prof Nurs. 2022;42:209–18.

Berg C, Philipp R, Taff SD. Scoping review of critical thinking literature in healthcare education. Occup Ther Health Care. 2023;37(1):18–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/07380577.2021.1879411 .

Kou M. A reward-learning framework of knowledge acquisition: an integrated account of curiosity, interest, and intrinsic-extrinsic rewards. Psychol Rev. 2022;129(1):175–98.

Nichols M, Cator K, Torres M. Challenge-based learner user guide. Digital Promise. Redwood City: ENGAGE; 2016.

Lund B, Jensen AA. In: Peters MA, editor. PBL Teachers in Higher Education: Challenges and Possibilities. Encyclopedia of Teacher Education Springer; 2020.

Gao X, Wang L, Deng J, Wan C, Mu D. The effect of the problem-based learning teaching model combined with mind mapping on nursing teaching: A meta-analysis. Nurse Educ Today. 2022;111:105306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2022 .

Manuaba IBAP, No Y, Wu CC. The effectiveness of problem-based learning in improving critical thinking, problem-solving and self-directed learning in first-year medical students: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2022;17(11):e0277339.

Archer-Kuhn B, MacKinnon S. Inquiry-based learning in higher education: A pedagogy of trust. J Educ Train Stud. 2020;8(9):1–14.

Betihavas V, Bridgman H, Kornhaber R, Cross M. The evidence for ‘flipping out’: a systematic review of the flipped classroom in nursing education. Nurse Educ Today. 2016;38:15–21.

Nugraheni BI, Surjono HD, Aji GP. How can flipped classroom develop critical thinking skills? A literature review. Int J Inform Educ Technol. 2022;12(1):82–9.

Benner P, Sutphen M, Leonard V, Day L. Educating nurses: A call for radical transformation. Jossey-Bass; 2010.

Gonzalez L, Nielsen A, Lasater K. Developing students’ clinical reasoning skills: a faculty guide. J Nurs Educ. 2021;60(9):485–93.

Altun E, Yildirim N. What does critical thinking mean? Examination of pre-service teachers’ cognitive structures and definitions for critical thinking. Thinking Skills Creativity. 2023;49:101367.

Ilaslan E, Adibelli D, Tesjerecu G, Cura SU. Development of nursing students’ critical thinking and clinical decision-making skills. Teach Learn Nurs. 2023;18(1):152–9.

Lee DS, Abdullah KL, Chinna K, Subramanian P, Bachmann RT. Critical thinking skills of RNs: exploring demographic determinants. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2020;51(3):109–17.

Karlse B, Hillestad TM, Dysvik E. Abductive reasoning in nursing: Challenges and possibilities. Nurs Inq. 2021;28(1):e12374.

Wardaini S, Kusuma IW. Comparison of learning in inductive and deductive approach to increase student’s conceptual understanding based on international standard curriculum. J Pendidikan IPA Indonesia. 2020;9(1):70–8.

Ng SL, Mylopoulos M, Kangasjarvi E, Boyd VA, Teles S, Orsino A, Lingard L, Phelan S. Critically reflective practice and its sources: A qualitative exploration. Med Educ. 2020;54:312–9.

Rolfe G, Jasper M, Freshwater D. Critical reflection in practice: Generating knowledge for care. 2nd ed. London: Red Globe Press; 2011.

Berg E, Lepp M. The meaning and application of student-centered learning in nursing education: an integrative review of the literature. Nurs Educ Pract. 2023;69:103622.

Carter AG, Creedy DK, Sidebotham M. Efficacy of teaching methods used to develop critical thinking in nursing and midwifery undergraduate students: a systematic review of the literature. Nurs Educ Today. 2016;40:209–18.