- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

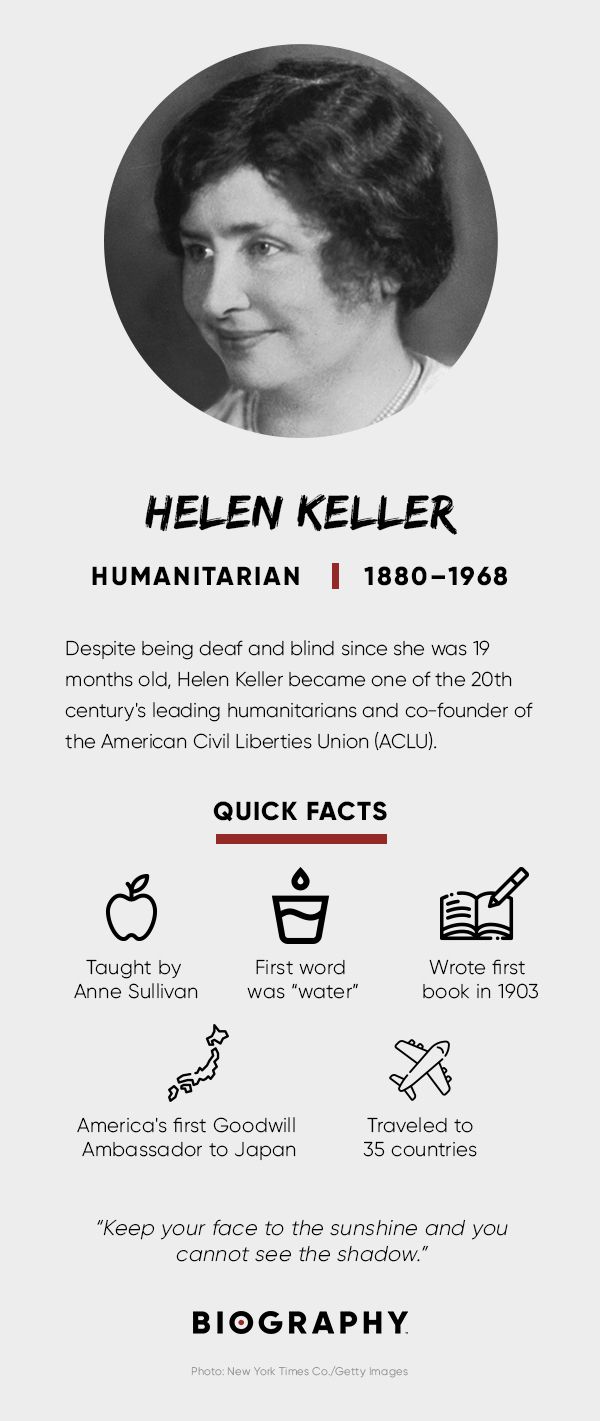

What were Helen Keller’s accomplishments?

What was helen keller’s relationship with anne sullivan, why is helen keller important.

- What was education like in ancient Athens?

- How does social class affect education attainment?

Helen Keller

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- HistoryNet - Helen Keller

- Social Welfare History Project - Biography of Helen Keller

- American Foundation for the Blind - Helen Keller

- Encyclopedia of Alabama - Helen Keller

- National Park Service - Helen Keller

- Spartacus Educational - Biography of Helen Keller

- International Journal of Research and Thoughts - Two Astonishing Personalities Anne Sullivan and Helen Keller and Their Heroic Companionship

- National Women's History Museum - Biography of Helen Keller

- Helen Keller - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Helen Keller - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

Who was Helen Keller?

Helen Keller was an American author and educator who was blind and deaf . Her education and training represent an extraordinary accomplishment in the education of persons with these disabilities.

Helen Keller’s personal accomplishment was developing skills never previously approached by any similarly disabled person. She also lectured on behalf of the American Foundation for the Blind, for which she later established a $2 million endowment fund. She then cofounded the American Civil Liberties Union with American civil rights activist Roger Nash Baldwin and others in 1920.

What books did Helen Keller write?

Helen Keller wrote about her life in several books, including The Story of My Life (1903), Optimism (1903), The World I Live In (1908), My Religion (1927), Helen Keller’s Journal (1938), and The Open Door (1957).

When did Helen Keller die?

Helen Keller died on June 1, 1968, in Easton, Connecticut, at the age of 87. She had bought her home in Easton in 1936 and called it Arcan Ridge, and it remained her permanent residence until her death.

Anne Sullivan became governess to six-year-old Helen Keller in March 1887. In 1888 the two began spending periods at the Perkins Institution, and Sullivan subsequently accompanied Keller to the Wright-Humason School in New York City , the Cambridge School for Young Ladies, and Radcliffe College . Sullivan was Keller’s constant companion at home and on lecture tours until Sullivan’s death in 1936.

Helen Keller was an author, activist, and educator whose lifetime of public advocacy for many communities and causes had lasting global impact. Keller, who became blind and deaf as a result of a childhood illness, learned to communicate with hearing people by having signals pressed into her palm, reading lips by way of touch, reading and writing Braille , and eventually speaking audibly. She helped to change perceptions of the deaf community and the blind community.

Helen Keller (born June 27, 1880, Tuscumbia , Alabama , U.S.—died June 1, 1968, Westport , Connecticut) was an American author and educator who was blind and deaf . Her education and training represent an extraordinary accomplishment in the education of persons with these disabilities.

Keller was afflicted at the age of 19 months with an illness (possibly scarlet fever ) that left her blind and deaf. She was examined by Alexander Graham Bell at the age of 6. As a result, he sent to her a 20-year-old teacher, Anne Sullivan (Macy) from the Perkins Institution for the Blind in Boston, which Bell’s son-in-law directed. Sullivan, a remarkable teacher, remained with Keller from March 1887 until her own death in October 1936.

Within months Keller had learned to feel objects and associate them with words spelled out by finger signals on her palm, to read sentences by feeling raised words on cardboard, and to make her own sentences by arranging words in a frame. During 1888–90 she spent winters at the Perkins Institution learning Braille . Then she began a slow process of learning to speak under Sarah Fuller of the Horace Mann School for the Deaf, also in Boston. She also learned to lip-read by placing her fingers on the lips and throat of the speaker while the words were simultaneously spelled out for her. At age 14 she enrolled in the Wright-Humason School for the Deaf in New York City , and at 16 she entered the Cambridge School for Young Ladies in Massachusetts. She won admission to Radcliffe College in 1900 and graduated cum laude in 1904.

Having developed skills never approached by any similarly disabled person, Keller began to write of blindness , a subject then taboo in women’s magazines because of the relationship of many cases to venereal disease . Edward W. Bok accepted her articles for the Ladies’ Home Journal , and other major magazines— The Century , McClure’s , and The Atlantic Monthly —followed suit.

She wrote of her life in several books, including The Story of My Life (1903), Optimism (1903), The World I Live In (1908), Light in My Darkness and My Religion (1927), Helen Keller’s Journal (1938), and The Open Door (1957). In 1913 she began lecturing (with the aid of an interpreter), primarily on behalf of the American Foundation for the Blind, for which she later established a $2 million endowment fund, and her lecture tours took her several times around the world. She cofounded the American Civil Liberties Union with American civil rights activist Roger Nash Baldwin and others in 1920. Her efforts to improve treatment of the deaf and the blind were influential in removing the disabled from asylums. She also prompted the organization of commissions for the blind in 30 states by 1937.

Keller’s childhood training with Sullivan was depicted in William Gibson’s play The Miracle Worker (1959), which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1960 and was subsequently made into a motion picture (1962), starring Anne Bancroft as Sullivan and Patty Duke as Keller, that won two Academy Awards .

Helen Keller

American educator Helen Keller overcame the adversity of being blind and deaf to become one of the 20th century's leading humanitarians as well as co-founder of the ACLU.

We may earn commission from links on this page, but we only recommend products we back.

(1880-1968)

Who Was Helen Keller?

Early life and family, loss of sight and hearing, keller's teacher, anne sullivan, 'the story of my life', social activism, 'the miracle worker' movie, awards and honors, quick facts:.

Helen Keller was an American educator, advocate for the blind and deaf and co-founder of the ACLU. Stricken by an illness at the age of 2, Keller was left blind and deaf. Beginning in 1887, Keller's teacher, Anne Sullivan, helped her make tremendous progress with her ability to communicate, and Keller went on to college, graduating in 1904. During her lifetime, she received many honors in recognition of her accomplishments.

Keller was born on June 27, 1880, in Tuscumbia, Alabama. Keller was the first of two daughters born to Arthur H. Keller and Katherine Adams Keller. Keller's father had served as an officer in the Confederate Army during the Civil War . She also had two older stepbrothers.

The family was not particularly wealthy and earned income from their cotton plantation. Later, Arthur became the editor of a weekly local newspaper, the North Alabamian .

Keller was born with her senses of sight and hearing, and started speaking when she was just 6 months old. She started walking at the age of 1.

Keller lost both her sight and hearing at just 19 months old. In 1882, she contracted an illness — called "brain fever" by the family doctor — that produced a high body temperature. The true nature of the illness remains a mystery today, though some experts believe it might have been scarlet fever or meningitis.

Within a few days after the fever broke, Keller's mother noticed that her daughter didn't show any reaction when the dinner bell was rung, or when a hand was waved in front of her face.

As Keller grew into childhood, she developed a limited method of communication with her companion, Martha Washington, the young daughter of the family cook. The two had created a type of sign language. By the time Keller was 7, they had invented more than 60 signs to communicate with each other.

During this time, Keller had also become very wild and unruly. She would kick and scream when angry, and giggle uncontrollably when happy. She tormented Martha and inflicted raging tantrums on her parents. Many family relatives felt she should be institutionalized.

Keller worked with her teacher Anne Sullivan for 49 years, from 1887 until Sullivan's death in 1936. In 1932, Sullivan experienced health problems and lost her eyesight completely. A young woman named Polly Thomson, who had begun working as a secretary for Keller and Sullivan in 1914, became Keller's constant companion upon Sullivan's death.

Looking for answers and inspiration, Keller's mother came across a travelogue by Charles Dickens, American Notes, in 1886. She read of the successful education of another deaf and blind child, Laura Bridgman, and soon dispatched Keller and her father to Baltimore, Maryland to see specialist Dr. J. Julian Chisolm.

After examining Keller, Chisolm recommended that she see Alexander Graham Bell , the inventor of the telephone, who was working with deaf children at the time. Bell met with Keller and her parents, and suggested that they travel to the Perkins Institute for the Blind in Boston, Massachusetts.

There, the family met with the school's director, Michael Anaganos. He suggested Keller work with one of the institute's most recent graduates, Sullivan.

On March 3, 1887, Sullivan went to Keller's home in Alabama and immediately went to work. She began by teaching six-year-old Keller finger spelling, starting with the word "doll," to help Keller understand the gift of a doll she had brought along. Other words would follow.

At first, Keller was curious, then defiant, refusing to cooperate with Sullivan's instruction. When Keller did cooperate, Sullivan could tell that she wasn't making the connection between the objects and the letters spelled out in her hand. Sullivan kept working at it, forcing Keller to go through the regimen.

As Keller's frustration grew, the tantrums increased. Finally, Sullivan demanded that she and Keller be isolated from the rest of the family for a time, so that Keller could concentrate only on Sullivan's instruction. They moved to a cottage on the plantation.

In a dramatic struggle, Sullivan taught Keller the word "water"; she helped her make the connection between the object and the letters by taking Keller out to the water pump, and placing Keller's hand under the spout. While Sullivan moved the lever to flush cool water over Keller's hand, she spelled out the word w-a-t-e-r on Keller's other hand. Keller understood and repeated the word in Sullivan's hand. She then pounded the ground, demanding to know its "letter name." Sullivan followed her, spelling out the word into her hand. Keller moved to other objects with Sullivan in tow. By nightfall, she had learned 30 words.

In 1905, Sullivan married John Macy, an instructor at Harvard University, a social critic and a prominent socialist. After the marriage, Sullivan continued to be Keller's guide and mentor. When Keller went to live with the Macys, they both initially gave Keller their undivided attention. Gradually, however, Anne and John became distant to each other, as Anne's devotion to Keller continued unabated. After several years, the couple separated, though were never divorced.

In 1890, Keller began speech classes at the Horace Mann School for the Deaf in Boston. She would toil for 25 years to learn to speak so that others could understand her.

From 1894 to 1896, Keller attended the Wright-Humason School for the Deaf in New York City. There, she worked on improving her communication skills and studied regular academic subjects.

Around this time, Keller became determined to attend college. In 1896, she attended the Cambridge School for Young Ladies, a preparatory school for women.

As her story became known to the general public, Keller began to meet famous and influential people. One of them was the writer Mark Twain , who was very impressed with her. They became friends. Twain introduced her to his friend Henry H. Rogers, a Standard Oil executive.

Rogers was so impressed with Keller's talent, drive and determination that he agreed to pay for her to attend Radcliffe College. There, she was accompanied by Sullivan, who sat by her side to interpret lectures and texts. By this time, Keller had mastered several methods of communication, including touch-lip reading, Braille, speech, typing and finger-spelling.

Keller graduated, cum laude, from Radcliffe College in 1904, at the age of 24.

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S HELEN KELLER FACT CARD

With the help of Sullivan and Macy, Sullivan's future husband, Keller wrote her first book, The Story of My Life . Published in 1905, the memoirs covered Keller's transformation from childhood to 21-year-old college student.

'The Story of My Life' by Helen Keller

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, Keller tackled social and political issues, including women's suffrage, pacifism, birth control and socialism.

After college, Keller set out to learn more about the world and how she could help improve the lives of others. News of her story spread beyond Massachusetts and New England. Keller became a well-known celebrity and lecturer by sharing her experiences with audiences, and working on behalf of others living with disabilities. She testified before Congress, strongly advocating to improve the welfare of blind people.

In 1915, along with renowned city planner George Kessler, she co-founded Helen Keller International to combat the causes and consequences of blindness and malnutrition. In 1920, she helped found the American Civil Liberties Union .

When the American Federation for the Blind was established in 1921, Keller had an effective national outlet for her efforts. She became a member in 1924, and participated in many campaigns to raise awareness, money and support for the blind. She also joined other organizations dedicated to helping those less fortunate, including the Permanent Blind War Relief Fund (later called the American Braille Press).

Soon after she graduated from college, Keller became a member of the Socialist Party, most likely due in part to her friendship with John Macy. Between 1909 and 1921, she wrote several articles about socialism and supported Eugene Debs, a Socialist Party presidential candidate. Her series of essays on socialism, entitled "Out of the Dark," described her views on socialism and world affairs.

It was during this time that Keller first experienced public prejudice about her disabilities. For most of her life, the press had been overwhelmingly supportive of her, praising her courage and intelligence. But after she expressed her socialist views, some criticized her by calling attention to her disabilities. One newspaper, the Brooklyn Eagle , wrote that her "mistakes sprung out of the manifest limitations of her development."

In 1946, Keller was appointed counselor of international relations for the American Foundation of Overseas Blind. Between 1946 and 1957, she traveled to 35 countries on five continents.

In 1955, at age 75, Keller embarked on the longest and most grueling trip of her life: a 40,000-mile, five-month trek across Asia. Through her many speeches and appearances, she brought inspiration and encouragement to millions of people.

Keller's autobiography, The Story of My Life , was used as the basis for 1957 television drama The Miracle Worker .

In 1959, the story was developed into a Broadway play of the same title, starring Patty Duke as Keller and Anne Bancroft as Sullivan. The two actresses also performed those roles in the 1962 award-winning film version of the play.

During her lifetime, she received many honors in recognition of her accomplishments, including the Theodore Roosevelt Distinguished Service Medal in 1936, the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1964, and election to the Women's Hall of Fame in 1965.

Keller also received honorary doctoral degrees from Temple University and Harvard University and from the universities of Glasgow, Scotland; Berlin, Germany; Delhi, India; and Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa. She was named an Honorary Fellow of the Educational Institute of Scotland.

Keller died in her sleep on June 1, 1968, just a few weeks before her 88th birthday. Keller suffered a series of strokes in 1961 and spent the remaining years of her life at her home in Connecticut.

During her remarkable life, Keller stood as a powerful example of how determination, hard work, and imagination can allow an individual to triumph over adversity. By overcoming difficult conditions with a great deal of persistence, she grew into a respected and world-renowned activist who labored for the betterment of others.

FULL NAME: Helen Adams Keller BORN: June 27, 1880 BIRTHPLACE: Tuscumbia, AL DIED: June 1, 1968 ASTROLOGICAL SIGN: Cancer

We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

- Keep your face to the sunshine and you cannot see the shadow.

- One can never consent to creep when one feels an impulse to soar.

- Remember, no effort that we make to attain something beautiful is ever lost. Sometime, somewhere, somehow we shall find that which we seek.

- Gradually from naming an object we advance step by step until we have traversed the vast distance between our first stammered syllable and the sweep of thought in a line of Shakespeare.

- If it is true that the violin is the most perfect of musical instruments, then Greek is the violin of human thought.

- A happy life consists not in the absence, but in the mastery of hardships.

- The two greatest characters in the 19th century are Napoleon and Helen Keller. Napoleon tried to conquer the world by physical force and failed. Helen tried to conquer the world by power of mind — and succeeded!” (Mark Twain)

- The bulk of the world’s knowledge is an imaginary construction.

- We differ, blind and seeing, one from another, not in our senses, but in the use we make of them, in the imagination and courage with which we seek wisdom beyond the senses.

- [T]he mystery of language was revealed to me. I knew then that "w-a-t-e-r" meant the wonderful cool something that was flowing over my hand. That living word awakened my soul, gave it light, hope, joy, set it free!

- It is more difficult to teach ignorance to think than to teach an intelligent blind man to see the grandeur of Niagara.

- Everything has its wonders, even darkness and silence, and I learn, whatever state I may be in, therein to be content.

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

Suffragettes

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Harriet Tubman

Susan B. Anthony

Lucretia Mott

Emmeline Pankhurst

Carrie Chapman Catt

Kate Sheppard

Emily Davison

Molly Brown

Helen Keller

Undeterred by deafness and blindness, Helen Keller rose to become a major 20 th century humanitarian, educator and writer. She advocated for the blind and for women’s suffrage and co-founded the American Civil Liberties Union.

Born on June 27, 1880 in Tuscumbia, Alabama, Keller was the older of two daughters of Arthur H. Keller, a farmer, newspaper editor, and Confederate Army veteran, and his second wife Katherine Adams Keller, an educated woman from Memphis. Several months before Helen’s second birthday, a serious illness—possibly meningitis or scarlet fever—left her deaf and blind. She had no formal education until age seven, and since she could not speak, she developed a system for communicating with her family by feeling their facial expressions.

Recognizing her daughter’s intelligence, Keller’s mother sought help from experts including inventor Alexander Graham Bell, who had become involved with deaf children. Ultimately, she was referred to Anne Sullivan, a graduate of the Perkins School for the Blind, who became Keller’s lifelong teacher and mentor. Although Helen initially resisted her, Sullivan persevered. She used touch to teach Keller the alphabet and to make words by spelling them with her finger on Keller’s palm. Within a few weeks, Keller caught on. A year later, Sullivan brought Keller to the Perkins School in Boston, where she learned to read Braille and write with a specially made typewriter. Newspapers chronicled her progress. At fourteen, she went to New York for two years where she improved her speaking ability, and then returned to Massachusetts to attend the Cambridge School for Young Ladies. With Sullivan’s tutoring, Keller was admitted to Radcliffe College, graduating cum laude in 1904. Sullivan went with her, helping Keller with her studies. (Impressed by Keller, Mark Twain urged his wealthy friend Henry Rogers to finance her education.)

Even before she graduated, Keller published two books, The Story of My Life (1902) and Optimism (1903), which launched her career as a writer and lecturer. She authored a dozen books and articles in major magazines, advocating for prevention of blindness in children and for other causes.

Sullivan married Harvard instructor and social critic John Macy in 1905, and Keller lived with them. During that time, Keller’s political awareness heightened. She supported the suffrage movement, embraced socialism, advocated for the blind and became a pacifist during World War I. Keller’s life story was featured in the 1919 film, Deliverance . In 1920, she joined Jane Addams, Crystal Eastman, and other social activists in founding the American Civil Liberties Union; four years later she became affiliated with the new American Foundation for the Blind in 1924.

After Sullivan’s death in 1936, Keller continued to lecture internationally with the support of other aides, and she became one of the world’s most-admired women (though her advocacy of socialism brought her some critics domestically). During World War II, she toured military hospitals bringing comfort to soldiers.

A second film on her life won the Academy Award in 1955; The Miracle Worker —which centered on Sullivan—won the 1960 Pulitzer Prize as a play and was made into a movie two years later. Lifelong activist, Keller met several US presidents and was honored with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1964. She also received honorary doctorates from Glasgow, Harvard, and Temple Universities.

- “Helen Keller.” Perkins. Accessed February 4, 2015.

- “Helen Keller.” American Foundation for the Blind. Accessed February 4, 2015.

- "Helen Adams Keller." Dictionary of American Biography . New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1988. U.S. History in Context . Accessed February 4, 2015.

- "Keller, Helen." UXL Encyclopedia of U.S. History . Sonia Benson, Daniel E. Brannen, Jr., and Rebecca Valentine. Vol. 5. Detroit: UXL, 2009. 847-849. U.S. History in Context . Accessed February 4, 2015.

- Ozick, Cynthia. “What Helen Keller Saw.” The New Yorker. June 16, 2003. Accessed February 4, 2015.

- Weatherford, Doris. American Women's History: An A to Z of People, Organizations, Issues, and Events . New York: Prentice Hall, 1994.

- PHOTO: Library of Congress

MLA - Michals, Debra. "Helen Keller." National Women's History Museum. National Women's History Museum, 2015. Date accessed.

Chicago - Michals, Debra. "Helen Keller." National Women's History Museum. 2015. www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/helen-keller.

Helen Keller: Described and Captioned Educational Media

Helen Keller Biography, American Foundation for the Blind

Helen Keller, Perkins School for the Blind

Helen Keller Birthplace

Helen Keller International

The Miracle Worker (1962). Dir. Arthur Penn. (DVD) Film.

The Miracle Worker (2000). Dir. Nadia Tass. (DVD) Film.

Keller, Helen. The World I Live In . New York: NYRB Classics, 2004.

Ford, Carin. Helen Keller: Lighting the Way for the Blind and Deaf . Enslow Publishers, 2001.

Herrmann, Dorothy. Helen Keller: A Life . Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1998.

Related Biographies

Stacey Abrams

Abigail Smith Adams

Jane Addams

Toshiko Akiyoshi

Related background, agnes demille’s rodeo and images of women on the frontier, voices of change: analyzing speeches by lgbtq+ women, “when we sing, we announce our existence”: bernice johnson reagon and the american spiritual', mary church terrell .

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Helen Keller

By: History.com Editors

Updated: January 18, 2019 | Original: April 14, 2010

Helen Keller was an author, lecturer, and crusader for the handicapped. Born in Tuscumbia, Alabama , She lost her sight and hearing at the age of nineteen months to an illness now believed to have been scarlet fever. Five years later, on the advice of Alexander Graham Bell , her parents applied to the Perkins Institute for the Blind in Boston for a teacher, and from that school hired Anne Mansfield Sullivan. Through Sullivan’s extraordinary instruction, the little girl learned to understand and communicate with the world around her. She went on to acquire an excellent education and to become an important influence on the treatment of the blind and deaf.

Keller learned from Sullivan to read and write in Braille and to use the hand signals of the deaf-mute, which she could understand only by touch. Her later efforts to learn to speak were less successful, and in her public appearances she required the assistance of an interpreter to make herself understood. Nevertheless, her impact as educator, organizer, and fund-raiser was enormous, and she was responsible for many advances in public services to the handicapped.

With Sullivan repeating the lectures into her hand, Keller studied at schools for the deaf in Boston and New York City and graduated cum laude from Radcliffe College in 1904. Her unprecedented accomplishments in overcoming her disabilities made her a celebrity at an early age; at twelve she published an autobiographical sketch in the Youth’s Companion , and during her junior year at Radcliffe, she produced her first book, The Story of My Life , still in print in over fifty languages. Keller published four other books of her personal experiences as well as a volume on religion, one on contemporary social problems, and a biography of Anne Sullivan. She also wrote numerous articles for national magazines on the prevention of blindness and the education and special problems of the blind.

In addition to her many appearances on the lecture circuit, Keller in 1918 made a movie in Hollywood, Deliverance , to dramatize the plight of the blind and during the next two years supported herself and Sullivan on the vaudeville stage. She also spoke and wrote in support of women’s rights and other liberal causes and in 1940 strongly backed the United States’ entry into World War II .

In 1924, Keller joined the staff of the newly formed American Foundation for the Blind as an adviser and fund-raiser. Her international reputation and warm personality enabled her to enlist the support of many wealthy people, and she secured large contributions from Henry Ford , John D. Rockefeller , and leaders of the motion picture industry. When the AFB established a branch for the overseas blind, it was named Helen Keller International. Keller and Sullivan were the subjects of a Pulitzer Prize-winning play, The Miracle Worker, by William Gibson, which opened in New York in 1959 and became a successful Hollywood film in 1962.

Widely honored throughout the world and invited to the White House by every U.S. president from Grover Cleveland to Lyndon B. Johnson , Keller altered the world’s perception of the capacities of the handicapped. More than any act in her long life, her courage, intelligence, and dedication combined to make her a symbol of the triumph of the human spirit over adversity.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Find anything you save across the site in your account

How Helen Keller Learned to Write

Suspicion stalks fame; incredulity stalks great fame. At least three times—at the ages of eleven, twenty-three, and fifty-two—Helen Keller was assaulted by accusation, doubt, and overt disbelief. She was the butt of skeptics and the cynosure of idolaters. Mark Twain compared her to Joan of Arc, and pronounced her “fellow to Caesar, Alexander, Napoleon, Homer, Shakespeare and the rest of the immortals.” Her renown, he said, would endure a thousand years.

It has, so far, lasted more than a hundred, while steadily dimming. Fifty years ago, even twenty, nearly every ten-year-old knew who Helen Keller was. “The Story of My Life,” her youthful autobiography, was on the reading lists of most schools, and its author was popularly understood to be a heroine of uncommon grace and courage, a sort of worldly saint. Much of that worshipfulness has receded. No one nowadays, without intending satire, would place her alongside Caesar and Napoleon; and, in an era of earnest disabilities legislation, who would think to charge a stone-blind, stone-deaf woman with faking her experience?

Yet as a child she was accused of plagiarism, and in maturity of “verbalism”—substituting parroted words for firsthand perception. All this came about because she was at once liberated by language and in bondage to it, in a way few other human beings can fathom. The merely blind have the window of their ears, the merely deaf listen through their eyes. For Helen Keller there was no ameliorating “merely”; what she suffered was a totality of exclusion. The illness that annihilated her sight and hearing, and left her mute, has never been diagnosed. In 1882, when she was four months short of two years, medical knowledge could assert only “acute congestion of the stomach and brain,” though later speculation proposes meningitis or scarlet fever. Whatever the cause, the consequence was ferocity—tantrums, kicking, rages—but also an invented system of sixty simple signs, intimations of intelligence. The child could mimic what she could neither see nor hear: putting on a hat before a mirror, her father reading a newspaper with his glasses on. She could fold laundry and pick out her own things. Such quiet times were few. Having discovered the use of a key, she shut up her mother in a closet. She overturned her baby sister’s cradle. Her wants were physical, impatient, helpless, and nearly always belligerent.

She was born in Tuscumbia, Alabama, fifteen years after the Civil War, when Confederate consciousness was still inflamed. Her father, who had fought at Vicksburg, called himself a “gentleman farmer,” and edited a small Democratic weekly until, thanks to political influence, he was appointed a United States marshal. He was a zealous hunter who loved his guns and his dogs. Money was usually short; there were escalating marital angers. His second wife, Helen’s mother, was younger by twenty years, a spirited woman of intellect condemned to farmhouse toil. She had a strong literary side (Edward Everett Hale, the New Englander who wrote “The Man Without a Country,” was a relative) and read seriously and searchingly. In Charles Dickens’s “American Notes,” she learned about Laura Bridgman, a deaf-blind country girl who was being educated at the Perkins Institution for the Blind, in Boston. Ravaged by scarlet fever at the age of two, she was even more circumscribed than Helen Keller—she could neither smell nor taste. She was confined, Dickens said, “in a marble cell, impervious to any ray of light, or particle of sound,” lost to language beyond a handful of words unidiomatically strung together.

News of Laura Bridgman ignited hope—she had been socialized into a semblance of personhood, while Helen remained a small savage—and hope led, eventually, to Alexander Graham Bell. By then, the invention of the telephone was well behind him, and he was tenaciously committed to teaching the deaf to speak intelligibly. His wife was deaf; his mother had been deaf. When the six-year-old Helen was brought to him, he took her on his lap and instantly calmed her by letting her feel the vibrations of his pocket watch as it struck the hour. Her responsiveness did not register in her face; he described it as “chillingly empty.” But he judged her educable, and advised her father to apply to Michael Anagnos, the director of the Perkins Institution, for a teacher to be sent to Tuscumbia.

Anagnos chose Anne Mansfield Sullivan, a former student at Perkins. “Mansfield” was her own embellishment; it had the sound of gentility. If the fabricated name was intended to confer an elevated status, it was because Annie Sullivan, born into penury, had no status at all. At five, she contracted trachoma, a disease of the eye. Three years on, her mother died of tuberculosis and was buried in potter’s field—after which her father, a drunkard prone to beating his children, deserted the family. The half-blind Annie was tossed into the poorhouse at Tewksbury, Massachusetts, among syphilitic prostitutes and madmen. Decades later, recalling its “strangeness, grotesqueness and even terribleness,” Annie Sullivan wrote, “I doubt if life or for that matter eternity is long enough to erase the terrors and ugly blots scored upon my mind during those dismal years from 8 to 14.”

She was rescued from Tewksbury by a committee investigating its spreading notoriety, and was mercifully transferred to Perkins. She learned Braille and the manual alphabet—finger positions representing letters—and, at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, underwent two operations, which enabled her to read almost normally, though the condition of her eyes was fragile and inconsistent over her lifetime. After six years, she graduated from Perkins as class valedictorian. But what was to become of her? How was she to earn a living? Someone suggested that she might wash dishes or peddle needlework. “Sewing and crocheting are inventions of the devil,” she sneered. “I’d rather break stones on the king’s highway than hem a handkerchief.”

She went to Tuscumbia instead. She was twenty years old and had no experience suitable for what she would encounter in the despairs and chaotic defeats of the Keller household. The child she had come to educate threw cutlery, pinched, grabbed food off dinner plates, sent chairs tumbling, shrieked, struggled. She was strong, beautiful but for one protruding eye, unsmiling, painfully untamed: virtually her first act on meeting the new teacher was to knock out one of her front teeth. The afflictions of the marble cell had become inflictions. Annie demanded that Helen be separated from her family; her father could not bear to see his ruined little daughter disciplined. The teacher and her recalcitrant pupil retreated to a cottage on the grounds of the main house, where Annie was to be the sole authority.

What happened then and afterward she chronicled in letter after letter, to Anagnos and, more confidingly, to Mrs. Sophia Hopkins, the Perkins housemother who had given her shelter during school vacations. Mark Twain saw in Annie Sullivan a writer: “How she stands out in her letters!” he exclaimed. “Her brilliancy, penetration, originality, wisdom, character and the fine literary competencies of her pen—they are all there.” Jubilantly, she set down the progress, almost hour by hour, of an exuberant deliverance far more remarkable than Laura Bridgman’s frail and inarticulate release. Annie Sullivan’s method, insofar as she recognized it formally as a method, was pure freedom. Like any writer, she wrote and wrote and wrote, all day long: words, phrases, sentences, lines of poetry, descriptions of animals, trees, flowers, weather, skies, clouds, concepts—whatever lay before her or came usefully to mind. She wrote not on paper with a pen but with her fingers, spelling rapidly into the child’s alert palm. Mimicking unknowable configurations, Helen spelled the same letters back—but not until a connection was effected between finger-wriggling and its referent did mind break free.

This was, of course, the fabled incident at the well pump, when Helen suddenly understood that the pecking at her hand was inescapably related to the gush of cold water spilling over it. “Somehow,” the adult Helen Keller recollected, “the mystery of language was revealed to me.” In the course of a single month, from Annie’s arrival to her triumph in bridling the household despot, Helen had grown docile, affectionate, and tirelessly intent on learning from moment to moment. Her intellect was fiercely engaged, and when language began to flood it she rode on a salvational ark of words.

To Mrs. Hopkins, Annie wrote ecstatically:

Something within me tells me that I shall succeed beyond my dreams. . . . I know that [Helen] has remarkable powers, and I believe that I shall be able to develop and mould them. I cannot tell how I know these things. I had no idea a short time ago how to go to work; I was feeling about in the dark; but somehow I know now, and I know that I know. I cannot explain it; but when difficulties arise, I am not perplexed or doubtful. I know how to meet them; I seem to divine Helen’s peculiar needs. . . .

Already people are taking a deep interest in Helen. No one can see her without being impressed. She is no ordinary child, and people’s interest in her education will be no ordinary interest. Therefore let us be exceedingly careful in what we say and write about her. . . . My beautiful Helen shall not be transformed into a prodigy if I can help it.

At this time, Helen was not yet seven years old, and Annie was being paid twenty-five dollars a month.

The public scrutiny Helen Keller aroused far exceeded Annie’s predictions. It was Michael Anagnos who first proclaimed her to be a miracle child—a young goddess. “History presents no case like hers,” he exulted. “As soon as a slight crevice was opened in the outer wall of their twofold imprisonment, her mental faculties emerged full-armed from their living tomb as Pallas Athene from the head of Zeus.” And again: “She is the queen of precocious and brilliant children, Emersonian in temper, most exquisitely organized, with intellectual sight of unsurpassed sharpness and infinite reach, a true daughter of Mnemosyne.” Annie, the teacher of a flesh-and-blood child, protested: “His extravagant way of saying [these things] rubs me the wrong way. The simple facts would be so much more convincing!” But Anagnos’s glorifications caught fire: one year after Annie had begun spelling into her hand, Helen Keller was celebrated in newspapers all over America and Europe. When her dog was inadvertently shot, an avalanche of contributions poured in to replace it; unprompted, she directed that the money be set aside for the care of an impoverished deaf-blind boy at Perkins. At eight, she was taken to visit President Cleveland at the White House, and in Boston was introduced to many of the luminaries of the period: Oliver Wendell Holmes, John Greenleaf Whittier, Edward Everett Hale, and Bishop Phillips Brooks (who addressed her puzzlement over the nature of God). At nine, she wrote to Whittier, saluting him as “Dear Poet”:

I thought you would be glad to hear that your beautiful poems make me very happy. Yesterday I read “In School Days” and “My Playmate,” and I enjoyed them greatly. . . . It is very pleasant to live here in our beautiful world. I cannot see the lovely things with my eyes, but my mind can see them all, and so I am joyful all the day long.

When I walk out in my garden I cannot see the beautiful flowers, but I know that they are all around me; for is not the air sweet with their fragrance? I know too that the tiny lily-bells are whispering pretty secrets to their companions else they would not look so happy. I love you very dearly, because you have taught me so many lovely things about flowers and birds, and people.

Her dependence on Annie for the assimilation of her immediate surroundings was nearly total, but through the raised letters of Braille she could be altogether untethered: books coursed through her. In childhood, she was captivated by “Little Lord Fauntleroy,” Frances Hodgson Burnett’s story of a sunnily virtuous boy who melts a crusty old man’s heart; it became a secret template of her own character as she hoped she might always manifest it—not sentimentally but in full awareness of dread. She was not deaf to Caliban’s wounded cry: “You taught me language, and my profit on’t / Is, I know how to curse.” Helen Keller’s profit was that she knew how to rejoice. In young adulthood, she seized on Swedenborgian spiritualism. Annie had kept away from teaching any religion at all: she was a down-to-earth agnostic whom Tewksbury had cured of easy belief. When Helen’s responsiveness to bitter social deprivation later took on a worldly strength, leading her to socialism, and even to unpopular Bolshevik sympathies, Annie would have no part of it, and worried that Helen had gone too far. Marx was not in Annie’s canon. Homer, Virgil, Shakespeare, and Milton were: she had Helen reading “Paradise Lost” at twelve.

But Helen’s formal schooling was widening beyond Annie’s tutelage. With her teacher at her side—and the financial support of such patrons as John Spaulding, the Sugar King, and Henry Rogers, of Standard Oil—Helen spent a year at Perkins, and then entered the Wright-Humason School, in New York, a fashionable academy for deaf girls; she was its single deaf-blind pupil. She was also determined to learn to speak like other people, but her efforts could not be readily understood. Speech was not her only ambition: she intended to go to college. To prepare, she enrolled in the Cambridge School for Young Ladies, where she studied mathematics, German, French, Latin, and Greek and Roman history. In 1900, she was admitted to Radcliffe (then an “annex” to Harvard), still with Annie in attendance. Despite Annie’s presence in every class, diligently spelling the lecture into Helen’s hand, and wearing out her troubled eyes as she transcribed text after text into the manual alphabet, no one thought of granting her a degree along with Helen: the radiant miracle outshone the driven miracle worker. It was not uncommon for Annie Sullivan to play second fiddle to Helen Keller, or to be charged with being Helen’s jailer, or harrier, or ventriloquist. During examinations at Radcliffe, Annie was not permitted to be in the building. Otherwise, Helen relied on her own extraordinary memory and on Annie’s lightning fingers. Luckily, a second helper soon turned up: he was John Macy, a twenty-five-year-old English instructor at Harvard, a writer and editor, a fervent socialist, and, eventually, Annie Sullivan’s husband, eleven years her junior.

At Radcliffe, Helen became a writer. Charles Townsend Copeland—Harvard’s illustrious Copey, a professor of rhetoric—had encouraged her (as she put it to him in a grateful letter) “to make my own observations and describe the experiences peculiarly my own. Henceforth I am resolved to be myself, to live my own life and write my own thoughts.” Out of this came “The Story of My Life,” the autobiography of a twenty-one-year-old, published while she was still an undergraduate. It began as a series of sketches for the Ladies ’ Home Journal; the fee was three thousand dollars. John Macy described the laborious process:

When she began work at her story, more than a year ago, she set up on the Braille machine about a hundred pages of what she called “material,” consisting of detached episodes and notes put down as they came to her without definite order or coherent plan. . . . Then came the task where one who has eyes to see must help her. Miss Sullivan and I read the disconnected passages, put them into chronological order, and counted the words to be sure the articles should be the right length. All this work we did with Miss Keller beside us, referring everything, especially matters of phrasing, to her for revision. . . .

Her memory of what she had written was astonishing. She remembered whole passages, some of which she had not seen for many weeks, and could tell, before Miss Sullivan had spelled into her hand a half-dozen words of the paragraphs under discussion, where they belonged and what sentences were necessary to make the connections clear.

This method of collaboration continued throughout Helen Keller’s professional writing life; yet within these constraints the design and the sensibility were her own. She was a self-conscious stylist. Macy remarked that she had the courage of her metaphors—he meant that she sometimes let them carry her away—and Helen herself worried that her prose could now and then seem “periwigged.” To the contemporary ear, there is too much Victorian lace and striving uplift in her cadences; but the contemporary ear is scarcely entitled, simply by being contemporary, to set itself up as judge—every period is marked by a prevailing voice. Helen Keller’s earnestness is a kind of piety. It is as if Tennyson and the transcendentalists had together got hold of her typewriter. At the same time, she is embroiled in the whole range of human perplexity—except, tellingly, for irony. She has no “edge,” and why should she? Irony is a radar that seeks out the dark side; she had darkness enough. She rarely knew what part of her mind was instinct and what part was information, and she was cautious about the difference. “It is certain,” she wrote, “that I cannot always distinguish my own thoughts from those I read, because what I read becomes the very substance and texture of my mind. . . . It seems to me that the great difficulty of writing is to make the language of the educated mind express our confused ideas, half feelings, half thoughts, where we are little more than bundles of instinctive tendencies.” She who had once been incarcerated in the id did not require Freud to instruct her in its inchoate presence.

“The Story of My Life,” first published in 1903, is being honored in its centenary year by two new reissues, one from the Modern Library, edited and with a preface by James Berger, and the other from W. W. Norton, edited by Roger Shattuck with Dorothy Herrmann; Shattuck also supplies a thoughtful foreword and afterword. Much else accompanies the Keller text: Macy’s ample contribution to the original edition, as well as Annie’s indelible reports and Helen’s increasingly impressive letters from childhood on. All these elements together make up at least a partial biography, though they do not take us into Helen Keller’s astonishing future as world traveller and energetic advocate for the blind. (Two full biographies, “Helen Keller: A Life,” by Dorothy Herrmann, and “Helen and Teacher,” by Joseph P. Lash, flesh out her long and active life.) Macy was able to write about Helen nearly as authoritatively as Annie, but also (in private) more skeptically: after his marriage, the three of them, a feverishly literary crew, set up housekeeping in rural Wrentham, Massachusetts. Macy soon discovered that he had married not just a woman, and a moody one at that, but the infrastructure of a public institution. As Helen’s secondary amanuensis, he continued to be of use until the marriage foundered—on his profligacy with money, on Annie’s irritability (she scorned his uncompromising socialism), and, finally, on his accelerating alcoholism.

Because Macy was known to have assisted Helen in the preparation of “The Story of My Life,” the insinuations of control that often assailed Annie landed on him. Helen’s ideas, it was suggested, were really Macy’s; he had transformed her into a “Marxist propagandist.” It was true that she sympathized with his political bent, but she had arrived at her views independently. The charge of expropriation, of both thought and idiom, was old, and dogged her at intervals during her early and middle years: she was a fraud, a puppet, a plagiarist. She was false coin. She was “a living lie.”

Helen Keller was eleven when these words were first hurled at her by an infuriated Michael Anagnos. What brought on this defection was a little story she had written, called “The Frost King,” which she sent him as a birthday present. In the voice of a highly literary children’s narrative, it recounts how the “frost fairies” cause the season’s turning:

When the children saw the trees all aglow with brilliant colors they clapped their hands and shouted for joy, and immediately began to pick great bunches to take home. “The leaves are as lovely as the flowers!” cried they, in their delight.

Anagnos—doubtless clapping his hands and shouting for joy—immediately began to publicize Helen’s newest accomplishment. “The Frost King” appeared both in the Perkins alumni magazine and in another journal for the blind, which, following Anagnos, unhesitatingly named it “without parallel in the history of literature.” But more than a parallel was at stake; the story was found to be nearly identical to “The Frost Fairies,” by Margaret Canby, a writer of children’s books. Anagnos was humiliated, and fled headlong from adulation to excoriation. Feeling personally betrayed and institutionally discredited, he arranged an inquisition for the terrified Helen, standing her alone in a room before a jury of eight Perkins officials and himself, all mercilessly cross-examining her. Her mature recollection of Anagnos’s “court of investigation” registers as pitiably as the ordeal itself:

Mr. Anagnos, who loved me tenderly, thinking that he had been deceived, turned a deaf ear to the pleadings of love and innocence. He believed, or at least suspected, that Miss Sullivan and I had deliberately stolen the bright thoughts of another and imposed them on him to win his admiration. . . . As I lay in my bed that night, I wept as I hope few children have wept. I felt so cold, I imagined I should die before morning, and the thought comforted me. I think if this sorrow had come to me when I was older, it would have broken my spirit beyond repairing.

She was defended by Alexander Graham Bell, and by Mark Twain, who parodied the whole procedure with a thumping hurrah for plagiarism, and disgust for the egotism of “these solemn donkeys breaking a little child’s heart with their ignorant damned rubbish! . . . A gang of dull and hoary pirates piously setting themselves the task of disciplining and purifying a kitten that they think they’ve caught filching a chop!” Margaret Canby’s tale had been spelled to Helen perhaps three years before, and lay dormant in her prodigiously retentive memory; she was entirely oblivious of reproducing phrases not her own. The scandal Anagnos had precipitated left a lasting bruise. But it was also the beginning of a psychological, even a metaphysical, clarification that Helen refined and ratified as she grew older, when similar, if subtler, suspicions cropped up in the press. “The Story of My Life” was attacked in The Nation not for plagiarism in the usual sense but for the purloining of “things beyond her powers of perception with the assurance of one who has verified every word. . . . One resents the pages of second-hand description of natural objects.” The reviewer blamed her for the sin of vicariousness. “All her knowledge,” he insisted, “is hearsay knowledge.”

It was almost a reprise of the Perkins tribunal: she was again being confronted with the charge of inauthenticity. Anagnos’s rebuke—“Helen Keller is a living lie”—regularly resurfaced, in the form of a neurologist’s or a psychologist’s assessment, or in the reservations of reviewers. A French professor of literature, who was himself blind, determined that she was “a dupe of words, and her aesthetic enjoyment of most of the arts is a matter of auto-suggestion rather than perception.” A New Yorker interviewer complained, “She talks bookishly. . . . To express her ideas, she falls back on the phrases she has learned from books, and uses words that sound stilted, poetical metaphors.”

But the cruellest appraisal of all came, in 1933, from Thomas Cutsforth, a blind psychologist. By this time, Helen was fifty-two, and had published four additional autobiographical volumes. Cutsforth disparaged everything she had become. The wordless child she once was, he maintained, was closer to reality than what her teacher had made of her through the imposition of “word-mindedness.” He objected to her use of images such as “a mist of green,” “blue pools of dog violets,” “soft clouds tumbling.” All that, he protested, was “implied chicanery” and “a birthright sold for a mess of verbiage.” He criticized

the aims of the educational system in which [Helen Keller] has been confined during her whole life. Literary expression has been the goal of her formal education. Fine writing, regardless of its meaningful content, has been the end toward which both she and her teacher have striven. . . . Her own experiential life was rapidly made secondary, and it was regarded as such by the victim. . . . Her teacher’s ideals became her ideals, her teacher’s likes became her likes, and whatever emotional activity her teacher experienced she experienced.

For Cutsforth—and not only for him—she was the victim of language rather than its victorious master. She was no better than a copy; whatever was primary, and thereby genuine, had been stamped out. As for Annie, while here she was pilloried as her pupil’s victimizer, elsewhere she was pitied as a woman cheated of her own life by having sacrificed it to serve another. Either Helen was Annie’s slave or Annie was Helen’s.

Helen knew what she saw. Once, having been taken to the uppermost viewing platform of what was then the tallest building in the world, she defined her condition:

I will concede that my guides saw a thousand things that escaped me from the top of the Empire State Building, but I am not envious. For imagination creates distances that reach to the end of the world. . . . There was the Hudson—more like the flash of a swordblade than a noble river. The little island of Manhattan, set like a jewel in its nest of rainbow waters, stared up into my face, and the solar system circled about my head!

Her rebuttal to word-mindedness, to vicariousness, to implied chicanery and the living lie, was inscribed deliberately and defiantly in her images of “swordblade” and “rainbow waters.” The deaf-blind person, she wrote, “seizes every word of sight and hearing, because his sensations compel it. Light and color, of which he has no tactual evidence, he studies fearlessly, believing that all humanly knowable truth is open to him.” She was not ashamed of talking bookishly: it meant a ready access to the storehouse of history and literature. She disposed of her critics with a dazzling apothegm—“The bulk of the world’s knowledge is an imaginary construction”—and went on to contend that history itself “is but a mode of imagining, of making us see civilizations that no longer appear upon the earth.” Those who ridiculed her rendering of color she dismissed as “spirit-vandals” who would force her “to bite the dust of material things.” Her idea of the subjective onlooker was broader than that of physics, and while “red” may denote an explicit and measurable wavelength in the visible spectrum, in the mind it varies from the bluster of rage to the reticence of a blush: physics cannot cage metaphor.

She saw, then, what she wished, or was blessed, to see, and rightly named it imagination. In this she belongs to a broader class than that narrow order of the deaf-blind. Her class, her tribe, hears what no healthy ear can catch and sees what no eye chart can quantify. Her common language was not with the man who crushed a child for memorizing what the fairies do, or with the carpers who scolded her for the crime of a literary vocabulary. She was a member of the race of poets, the Romantic kind; she was close cousin to those novelists who write not only what they do not know but what they cannot possibly know.

And though she was early taken in hand by a writerly intelligence, it was hardly in the power of the manual alphabet to pry out a writer who was not already there. Laura Bridgman stuck to her lacemaking, and with all her senses intact might have remained a needlewoman. John Macy believed finally that between Helen and Annie there was only one genius—his wife. In the absence of Annie’s inventiveness and direction, he implied, Helen’s efforts would show up as the lesser gifts they were. This did not happen. Annie died, at seventy, in 1936, four years after Macy; they had long been estranged. Depressed, obese, cranky, and inconsolable, she had herself gone blind. Helen came under the care of her secretary, Polly Thomson, a loyal but unliterary Scotswoman: the scenes she spelled into Helen’s hand never matched Annie’s quicksilver evocations.

Even as Helen mourned the loss of her teacher, she flourished. With the assistance of Nella Henney, Annie Sullivan’s biographer, she continued to publish journals and memoirs. She undertook gruelling visits to Japan, India, Israel, Europe, Australia, everywhere championing the disabled and the dispossessed. She was indefatigable until her very last years, and died in 1968, weeks before her eighty-eighth birthday.

Yet the story of her life is not the good she did, the panegyrics she inspired, or the disputes (genuine or counterfeit? victim or victimizer?) that stormed around her. The most persuasive story of Helen Keller’s life is what she said it was: “I observe, I feel, I think, I imagine.” She was an artist. She imagined.

“Blindness has no limiting effect upon mental vision,” she argued again and again. “My intellectual horizon is infinitely wide. The universe it encircles is immeasurable.” And, like any writer making imagination’s mysterious claims before the material-minded, she had cause to cry out, “Oh, the supercilious doubters!”

Nevertheless, she was a warrior in a vaster and more vexing conflict. Do we know only what we see, or do we see what we somehow already know? Are we more than the sum of our senses? Does a picture—whatever strikes the retina—engender thought, or does thought create the picture? Can there be subjectivity without an object to glance off? Theorists have their differing notions, to which the ungraspable organism that is Helen Keller is a retort. She is not an advocate for one side or the other in the ancient debate concerning the nature of the real. She is not a philosophical or neurological or therapeutic topic. She stands for enigma; there lurks in her still the angry child who demanded to be understood yet could not be deciphered. She refutes those who cannot perceive, or do not care to value, what is hidden from sensation: collective memory, heritage, literature.

Helen Keller’s lot, it turns out, was not unique. “We work in the dark,” Henry James affirmed, on behalf of his own art; and so did she. It was the same dark. She knew her Wordsworth: “Visionary power / Attends the motions of the viewless winds, / Embodied in the mystery of words: / There, darkness makes abode.” She vivified Keats’s phantom theme of negative capability, the poet’s oarless casting about for the hallucinatory shadows of desire. She fought the debunkers who, for the sake of a spurious honesty, would denude her of landscape and return her to the marble cell. She fought the literalists who took imagination for mendacity, who meant to disinherit her, and everyone, of poetry. Her legacy, after all, is an epistemological marker of sorts: proof of the real existence of the mind’s eye.

In one respect, though, she was as fraudulent as the cynics charged. She had always been photographed in profile; this hid her disfigured left eye. In maturity, she had both eyes surgically removed and replaced with glass—an expedient known only to her intimates. Everywhere she went, her sparkling blue prosthetic eyes were admired for their living beauty and humane depth. ♦

As a name that is known worldwide, Helen Keller is a symbol of courage and hope. Yet, she is much more than a name or a symbol. She was a woman of astounding intelligence, unwavering determination, unbelievable courage and insurmountable achievement. She dedicated her entire life to the betterment of others, helping people see the potential in their own lives, as well as the lives of people around them. She became the first blind-deaf person to effectively communicate with the sighted and hearing world. In so doing, she became an international celebrity from the age of eight, even before the era of mass communications.

Helen Adams Keller was born on June, 27, 1880 to Arthur H. Keller and Kate Adams Keller in the small, north Alabama town of Tuscumbia. When she was only 19 months old, she contracted a fever that would leave her both deaf and blind. At almost seven years of age, her mother and father took her to see the famous inventor, Dr. Alexander Graham Bell, who advised them to hire a governess for the child.

On March 3, 1887, Anne Mansfield Sullivan, a partially blind, twenty-one year old woman, arrived in Tuscumbia to be Helen’s teacher. With patience, understanding and love, Miss Sullivan was able to save Helen from her “double dungeon of darkness and silence”.

With the help of her beloved teacher, Helen quickly and eagerly learned to read and write. After attending high school at the Perkins School for the Blind in Boston, Massachusetts, Miss Sullivan helped Helen enroll in Radcliffe College, formerly the all-male Harvard College’s coordinate institution for female students. With remarkable determination, Helen graduated Cum Laude in 1904, becoming the first deaf-blind person to graduate from college. At that time, she announced that her life would be dedicated to the amelioration of blindness.

After graduation, Helen Keller began her life’s work of helping blind and deaf-blind people. She appeared before state and national legislatures and international forums. She regarded herself as a “world citizen”, visiting 39 countries on five continents between 1939 and 1957. She published 14 books and produced numerous articles. Not only was she out-spoken on the needs and issues affecting her fellow deaf and deaf-blind comrades, Helen was also a valiant supporter of women’s suffrage, civil rights, and the labor union movement, as well as many other worthwhile and important causes.

Helen Keller’s pilgrimage from Tuscumbia, Alabama to worldwide recognition is an inspiring story that took her from silence and darkness to a life of vision and advocacy. Against overwhelming odds, she waged a seemingly impossible battle to re-enter the world she had lost. She is one of the most powerful symbols of triumph over adversity our era has produced, leading Winston Churchill to call her, “The greatest woman of our age”.

Helen Keller won numerous honors, including several honorary university degrees, the Lions Humanitarian Award, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the French Legion of Honor and election to the Women’s Hall of Fame. She also met every President of the United States, from Calvin Coolidge to John F. Kennedy.

Helen died on June 1, 1968 at the age of 87. She was laid to rest in St. Joseph’s Chapel, at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C. Her legacy reminds us that with faith and courage, we can overcome obstacles in our own lives. With endurance and determination, we can help to better the lives of those around us. With love and patience, we can leave this world a better place.

In 1968, Senator Lister Hill eulogized her as “One of the few persons not born to die”. She will always be known as “The first lady of courage”.

View photos of Helen Keller and those she touched.

View the chronology of Helen Keller’s life.

“To keep our faces toward change and behave like free spirits in the presence of fate, is strength un-defeatable.” -Helen Keller

Featured Reading

The Foundation understands that the message of courage and selflessness implied in Helen Keller’s legacy is and always will be important to transmit to new generations – both for its own value, and as a means to promote public understanding of vision and hearing research.

Continue Reading…

Help Advance Research

The Foundation’s research discoveries have the potential to save substantial sight and to reduce healthcare expenditures by $50 million annually. The research efforts have also generated more than 700 publications and presentations and earned a particularly strong reputation in the areas of eye trauma and surgical treatment of the center of vision, the macula. The Helen Keller Prize for Vision Research was established to honor research excellence and is now commonly regarded as the premier award in vision research.

Biography Online

Helen Keller Biography

“Once I knew the depth where no hope was, and darkness lay on the face of all things. Then love came and set my soul free. Once I knew only darkness and stillness. Now I know hope and joy.”

– Helen Keller, On Optimism (1903)

Short Biography of Helen Keller

In 1886, Helen was sent to see an eye, ear and nose specialist in Baltimore. He put them in touch with Alexander Graham Bell , who was currently investigate issues of deafness and sound (he would also develop the first telephone) Bell was moved by the experience of working with Keller, writing that:

“I feel that in this child I have seen more of the Divine than has been manifest in anyone I ever met before.”

Alexander Bell helped Keller to visit the Perkins Institute for the Blind, and this led to a long relationship with Anne Sullivan – who was a former student herself. Sullivan was visually impaired and, aged only 20, and with no prior experience, she set about teaching Helen how to communicate. The two maintained a long relationship of 49 years.

Learning to Communicate

In the beginning, Keller was frustrated by her inability to pick up the hand signals that Sullivan was giving. However, after a frustrating month, Keller picked up on Sullivan’s system of hand signals through understanding the word water. Sullivan poured water over Keller’s left hand and wrote out on her right hand the word ‘water’. This helped Helen to fully understand the system, and she was soon able to identify a variety of household objects.

“The most important day I remember in all my life is the one on which my teacher, Anne Mansfield Sullivan, came to me. I am filled with wonder when I consider the immeasurable contrasts between the two lives which it connects. It was the third of March, 1887, three months before I was seven years old.”

– Helen Keller, The Story of My Life , 1903, Ch. 4

Keller came into contact with American author, Mark Twain . Twain admired the perseverance of Keller and helped persuade Henry Rogers, an oil businessman to fund her education. With great difficulty, Keller was able to study at Radcliffe College, where in 1904, she was able to graduate with a Bachelor of Arts degree. During her education, she also learned to speak and practise lip-reading. Her sense of touch became extremely subtle. She also found that deafness and blindness encouraged her to develop wisdom and understanding from beyond the senses.

“We differ, blind and seeing, one from another, not in our senses, but in the use we make of them, in the imagination and courage with which we seek wisdom beyond the senses.”

― Helen Keller , The Five-sensed World (1910)

Keller became a proficient writer and speaker. In 1903, she published an autobiography ‘ The Story of My Life ‘ It recounted her struggles to overcome her disabilities and the way it forced her to look at life from a different perspective.

“When one door of happiness closes, another opens; but often we look so long at the closed door that we do not see the one which has been opened for us.”

― Helen Keller

Political Views

Keller also wrote on political issues, Keller was a staunch supporter of the American Socialist party and joined the party in 1909. She wished to see a fairer distribution of income, and an end to the inequality of Capitalist society. She said she became a more convinced socialist after the 1912 miners strike. Her book ‘ Out of the Dark ‘ (1913) includes several essays on socialism. She supported Eugene V Debs, in each of the Presidential elections he stood for. In 1912, she joined the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW); as well as advocating socialism, Keller was a pacifist and opposed the American involvement in World War One.

Religious Views

In religious matters, she advocated the teachings of Emanuel Swedenborg, a Christian theologian who advocated a particular spiritual interpretation of the Bible. She published ‘ My Religion ‘ in 1927.

Charity Work

From 1918, she devoted much of her time to raising funds and awareness for blind charities. She sought to raise money and also improve the living conditions of the blind, who at the time were often badly educated and living in asylums. Her public profile helped to de-stigmatise blindness and deafness. She was also noted for her optimism which she sought to cultivate.

“If I am happy in spite of my deprivations, if my happiness is so deep that it is a faith, so thoughtful that it becomes a philosophy of life, — if, in short, I am an optimist, my testimony to the creed of optimism is worth hearing.”

― Helen Keller, Optimism (1903)

Towards the end of her life, she suffered a stroke, and she died in her sleep on June 1, 1968. She was given numerous awards during her life, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1964, by Lyndon B. Johnson.

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan . “Biography of Helen Keller ”, Oxford, UK www.biographyonline.net , Published: 1st Feb. 2014. Last updated 3rd March 2017.

Hellen Keller – The Story of My Life

Hellen Keller – The Story of My Life at Amazon

The Biography of Helen Keller

Helen Adams Keller was born a healthy child on June 27, 1880, to Captain Arthur H. and Kate Adams Keller of Tuscumbia. Her father, Arthur H. Keller, was a retired Confederate Army captain and editor of the local newspaper. Her mother, Kate Keller, was an educated young woman from Memphis.

When Helen Keller was 19 months old, she was afflicted by an unknown illness, possibly scarlet fever or meningitis, which left her deaf and blind.

Helen was quite intelligent and tried to learn in her own way with taste, feel and smell. She developed a rudimentary sign language with which to communicate, but soon she realized that her family members could communicate with their mouths instead of signing. This left her isolated, unruly and prone to wild tantrums. Some members of her family considered institutionalizing her.

Keller would later write in her autobiography, “the need of some means of communication became so urgent that these outbursts occurred daily, sometimes hourly.”

Seeking to improve her condition, in 1886 Helen and her parents traveled from their Alabama home to Baltimore, Maryland, to see an oculist who had had some success in dealing with conditions of the eye. After examining Keller, he told her parents that he could not restore her sight, but suggested that she could still be educated, referring them to Alexander Graham Bell, who despite having achieved worldwide fame with the invention of the telephone, was working with deaf children in Washington, D.C.

After the visit Bell connected the Kellers to The Perkins Institute and by March 3, 1887 Anne Sullivan came to Ivy Green to be Helen’s teacher. The strong willed Sullivan, a recent graduate of the Perkins school, met her match in Helen. The two worked together even though Helen pinched, hit, kicked and even knocked out one of Anne’s teeth. Once she had gained Helen’s trust, the real work could begin.

Anne began teaching Helen using finger spelling into the child’s hand. Although Helen enjoyed this, she didn’t understand it truly until Sullivan was steadily pumping cool water into one of the girl’s hands while repeatedly tapping out the five letters in W-A-T-E-R. She continued finger spelling while pumping the water again and again as young Helen painstakingly struggled to break her world of silence.

Suddenly the signals crossed Helen’s consciousness with a meaning. By nightfall, Helen had learned 30 words using this process.

After Helen’s miraculous break-through at the simple well-pump, she proved so gifted that she soon learned the fingertip alphabet and shortly afterward to write. By the end of August, in six short months, she knew 625 words.

By age 10, Helen had mastered Braille as well as the manual alphabet and even learned to use the typewriter. By the time she was 16, Helen could speak well enough to go to preparatory school and to college. Sullivan interpreted lectures and class discussions to Helen. In 1904 she became the first deaf-blind person to graduate cum laude from Radcliffe College.

Helen became one of history’s most remarkable women. She dedicated her life to improving the conditions of the visually impaired and the hearing impaired around the world, lecturing in more than 25 countries. She helped to create the American Civil Liberties Union advocating for the rights of women and of those with disabilities.

During her life she performed on the Vaudeville circuit, earned an Oscar, was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize, traveled to 25 countries and met every President from Grover Cleveland to John F. Kennedy, 12 to be exact.

Keller stopped her public appearances in 1961 after she suffered a series of strokes. She was unable to attend the ceremony when President Lyndon B. Johnson awarded her with the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Keller’s 1968 funeral was held at the National Cathedral, and more than 1,200 people were in attendance. Alabama Senator Lister Hill gave the eulogy. He said, “She will live on, one of the few, the immortal names not born to die. Her spirit will endure as long as man can read and stories can be told of the woman who showed the world there are no boundaries to courage and faith.”

Helen is interred at the National Cathedral in Washington D.C. in the Chapel of St. Joseph of Arimathea.

A Cathedral crypt is just off that chapel. A small, bronze plaque on the wall shows this is Keller’s final resting place. The plaque simply states: “Helen Keller and her lifelong companion Anne Sullivan Macy are interred in the columbarium behind this chapel.” Those same words are also written in Braille.

Although only Keller’s and Sullivan’s names are listed on the plaque, Polly Thomson, Keller’s companion later in life, is also interred with the other two women’s ashes.

- Humanities ›

- History & Culture ›

- The 20th Century ›

- People & Events ›

Biography of Helen Keller, Deaf and Blind Spokesperson and Activist

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

- People & Events

- Fads & Fashions

- Early 20th Century

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- Women's History

- B.A., English Literature, University of Houston

Helen Adams Keller (June 27, 1880–June 1, 1968) was a groundbreaking exemplar and advocate for the blind and deaf communities. Blind and deaf from a nearly fatal illness at 19 months old, Helen Keller made a dramatic breakthrough at the age of 6 when she learned to communicate with the help of her teacher, Annie Sullivan. Keller went on to live an illustrious public life, inspiring people with disabilities and fundraising, giving speeches, and writing as a humanitarian activist.

Fast Facts: Helen Keller

- Known For : Blind and deaf from infancy, Helen Keller is known for her emergence from isolation, with the help of her teacher Annie Sullivan, and for a career of public service and humanitarian activism.

- Born : June 27, 1880 in Tuscumbia, Alabama

- Parents : Captain Arthur Keller and Kate Adams Keller

- Died : June 1, 1968 in Easton Connecticut

- Education : Home tutoring with Annie Sullivan, Perkins Institute for the Blind, Wright-Humason School for the Deaf, studies with Sarah Fuller at the Horace Mann School for the Deaf, The Cambridge School for Young Ladies, Radcliffe College of Harvard University

- Published Works : The Story of My Life, The World I Live In, Out of the Dark, My Religion, Light in My Darkness, Midstream: My Later Life