Carl Rogers Humanistic Theory and Contribution to Psychology

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Carl Rogers (1902-1987) was a humanistic psychologist best known for his views on the therapeutic relationship and his theories of personality and self-actualization.

Rogers (1959) believed that for a person to “grow”, they need an environment that provides them with genuineness (openness and self-disclosure ), acceptance (being seen with unconditional positive regard), and empathy (being listened to and understood).

Without these qualities, relationships and healthy personalities will not develop as they should, much like a tree will not grow without sunlight and water.

Rogers believed that every person could achieve their goals, wishes, and desires in life. When, or rather if they did so, self-actualization took place. This was one of Carl Rogers most important contributions to psychology, and for a person to reach their potential a number of factors must be satisfied.

Person-Centered Therapy

Rogers developed client-centered therapy (later re-named ‘person-centered’), a non-directive therapy, allowing clients to deal with what they considered important, at their own pace.

This method involves removing obstacles so the client can move forward, freeing him or her for normal growth and development. By using non-directive techniques, Rogers assisted people in taking responsibility for themselves.

He believed that the experience of being understood and valued gives us the freedom to grow, while pathology generally arises from attempting to earn others’ positive regard rather than following an ‘inner compass’.

Rogers recorded his therapeutic sessions, analyzed their transcripts, and examined factors related to the therapy outcome. He was the first person to record and publish complete cases of psychotherapy .

Rogers revolutionized the course of therapy. He took the, then, radical view that it might be more beneficial for the client to lead the therapy sessions rather than the therapist; as he says, ‘the client knows what hurts, what directions to go, what problems are crucial, what experiences have been buried’ (Rogers, 1961).

Personality Development

Central to Rogers’ personality theory is the notion of self or self-concept . This is “the organized, consistent set of perceptions and beliefs about oneself.”

Carl Rogers’ self-concept is a central theme in his humanistic theory of psychology. It encompasses an individual’s self-image (how they see themselves), self-esteem (how much value they place on themselves), and ideal self (the person they aspire to be).

The self is the humanistic term for who we really are as a person. The self is our inner personality, and can be likened to the soul, or Freud’s psyche . The self is influenced by the experiences a person has in their life, and out interpretations of those experiences.

Two primary sources that influence our self-concept are childhood experiences and evaluation by others.

According to Rogers (1959), we want to feel, experience, and behave in ways consistent with our self-image and which reflect what we would like to be like, our ideal self. The closer our self-image and ideal self are to each other, the more consistent or congruent we are and the higher our sense of self-worth.

Discrepancies between self-concept and reality can cause incongruence, leading to psychological tension and anxiety. A person is said to be in a state of incongruence if some of the totality of their experience is unacceptable to them and is denied or distorted in the self-image.

The humanistic approach states that the self is composed of concepts unique to ourselves. The self-concept includes three components:

Self-worth (or self-esteem ) is the value or worth an individual places on themselves. It’s the evaluative aspect of self-concept, influenced by the individual’s perceived successes, failures, and how they believe others view them.

High self-esteem indicates a positive self-view, while low self-esteem signifies self-doubt and criticism.

Rogers believed feelings of self-worth developed in early childhood and were formed from the interaction of the child with the mother and father.

Self-image refers to individuals’ mental representation of themselves, shaped by personal experiences and interactions with others.

It’s how people perceive their physical and personality traits, abilities, values, roles, and goals. It’s their understanding of “who I am.”

How we see ourselves, which is important to good psychological health. Self-image includes the influence of our body image on our inner personality.

At a simple level, we might perceive ourselves as a good or bad person, beautiful or ugly. Self-image affects how a person thinks, feels, and behaves in the world.

Self-image vs. Real self

The self-image can sometimes be distorted or based on inaccurate perceptions . In contrast, the real self includes self-awareness of who a person truly is.

The real self represents a person’s genuine current state, including their strengths, weaknesses, and areas where they might struggle.

The ideal self is the version of oneself that an individual aspires to become.

It includes all the goals, values, and traits a person deems ideal or desirable. It’s their vision of “who I want to be.”

This is the person who we would like to be. It consists of our goals and ambitions in life, and is dynamic – i.e., forever changing. The ideal self in childhood is not the ideal self in our teens or late twenties.

According to Rogers, congruence between self-image and the ideal self signifies psychological health.

If the ideal self is unrealistic or there’s a significant disparity between the real and ideal self, it can lead to incongruence, resulting in dissatisfaction, unhappiness, and even mental health issues.

Therefore, as per Rogers, one of the goals of therapy is to help people bring their real self and ideal self into alignment, enhancing their self-esteem and overall life satisfaction.

Positive Regard and Self Worth

Carl Rogers (1951) viewed the child as having two basic needs: positive regard from other people and self-worth.

How we think about ourselves and our feelings of self-worth are of fundamental importance to psychological health and the likelihood that we can achieve goals and ambitions in life and self-actualization.

Self-worth may be seen as a continuum from very high to very low. To Carl Rogers (1959), a person with high self-worth, that is, has confidence and positive feelings about him or herself, faces challenges in life, accepts failure and unhappiness at times, and is open with people.

A person with low self-worth may avoid challenges in life, not accept that life can be painful and unhappy at times, and will be defensive and guarded with other people.

Rogers believed feelings of self-worth developed in early childhood and were formed from the interaction of the child with the mother and father. As a child grows older, interactions with significant others will affect feelings of self-worth.

Rogers believed that we need to be regarded positively by others; we need to feel valued, respected, treated with affection and loved. Positive regard is to do with how other people evaluate and judge us in social interaction. Rogers made a distinction between unconditional positive regard and conditional positive regard.

Unconditional Positive Regard

Unconditional positive regard is a concept in psychology introduced by Carl Rogers, a pioneer in client-centered therapy.

Unconditional positive regard is where parents, significant others (and the humanist therapist) accept and loves the person for what he or she is, and refrain from any judgment or criticism.

Positive regard is not withdrawn if the person does something wrong or makes a mistake.

Unconditional positive regard can be used by parents, teachers, mentors, and social workers in their relationships with children, to foster a positive sense of self-worth and lead to better outcomes in adulthood.

For example

In therapy, it can substitute for any lack of unconditional positive regard the client may have experienced in childhood, and promote a healthier self-worth.

The consequences of unconditional positive regard are that the person feels free to try things out and make mistakes, even though this may lead to getting it worse at times.

People who are able to self-actualize are more likely to have received unconditional positive regard from others, especially their parents, in childhood.

Examples of unconditional positive regard in counseling involve the counselor maintaining a non-judgmental stance even when the client displays behaviors that are morally wrong or harmful to their health or well-being.

The goal is not to validate or condone these behaviors, but to create a safe space for the client to express themselves and navigate toward healthier behavior patterns.

This complete acceptance and valuing of the client facilitates a positive and trusting relationship between the client and therapist, enabling the client to share openly and honestly.

Limitations

While simple to understand, practicing unconditional positive regard can be challenging, as it requires setting aside personal opinions, beliefs, and values.

It has been criticized as potentially inauthentic, as it might require therapists to suppress their own feelings and judgments.

Critics also argue that it may not allow for the challenging of unhelpful behaviors or attitudes, which can be useful in some therapeutic approaches.

Finally, some note a lack of empirical evidence supporting its effectiveness, though this is common for many humanistic psychological theories (Farber & Doolin, 2011).

Conditional Positive Regard

Conditional positive regard is a concept in psychology that refers to the expression of acceptance and approval by others (often parents or caregivers) only when an individual behaves in a certain acceptable or approved way.

In other words, this positive regard, love, or acceptance is conditionally based on the individual’s behaviors, attitudes, or views aligning with those expected or valued by the person giving the regard.

According to Rogers, conditional positive regard in childhood can lead to conditions of worth in adulthood, where a person’s self-esteem and self-worth may depend heavily on meeting certain standards or expectations.

These conditions of worth can create a discrepancy between a person’s real self and ideal self, possibly leading to incongruence and psychological distress.

Conditional positive regard is where positive regard, praise, and approval, depend upon the child, for example, behaving in ways that the parents think correct.

Hence the child is not loved for the person he or she is, but on condition that he or she behaves only in ways approved by the parent(s).

For example, if parents only show love and approval when a child gets good grades or behaves in ways they approve, the child may grow up believing they are only worthy of love and positive regard when they meet certain standards.

This may hinder the development of their true self and could contribute to struggles with self-esteem and self-acceptance.

At the extreme, a person who constantly seeks approval from other people is likely only to have experienced conditional positive regard as a child.

Congruence & Incongruence

A person’s ideal self may not be consistent with what actually happens in life and the experiences of the person. Hence, a difference may exist between a person’s ideal self and actual experience. This is called incongruence.

Where a person’s ideal self and actual experience are consistent or very similar, a state of congruence exists. Rarely, if ever, does a total state of congruence exist; all people experience a certain amount of incongruence.

The development of congruence is dependent on unconditional positive regard. Carl Rogers believed that for a person to achieve self-actualization, they must be in a state of congruence.

According to Rogers, we want to feel, experience, and behave in ways which are consistent with our self-image and which reflect what we would like to be like, our ideal-self.

The closer our self-image and ideal-self are to each other, the more consistent or congruent we are and the higher our sense of self-worth. A person is said to be in a state of incongruence if some of the totality of their experience is unacceptable to them and is denied or distorted in the self-image.

Incongruence is “a discrepancy between the actual experience of the organism and the self-picture of the individual insofar as it represents that experience.

As we prefer to see ourselves in ways that are consistent with our self-image, we may use defense mechanisms like denial or repression in order to feel less threatened by some of what we consider to be our undesirable feelings.

A person whose self-concept is incongruent with her or his real feelings and experiences will defend himself because the truth hurts.

Self Actualization

The organism has one basic tendency and striving – to actualize, maintain, and enhance the experiencing organism (Rogers, 1951, p. 487).

Rogers rejected the deterministic nature of both psychoanalysis and behaviorism and maintained that we behave as we do because of the way we perceive our situation. “As no one else can know how we perceive, we are the best experts on ourselves.”

Carl Rogers (1959) believed that humans have one basic motive, which is the tendency to self-actualize – i.e., to fulfill one’s potential and achieve the highest level of “human-beingness” we can.

According to Rogers, people could only self-actualize if they had a positive view of themselves (positive self-regard). This can only happen if they have unconditional positive regard from others – if they feel that they are valued and respected without reservation by those around them (especially their parents when they were children).

Self-actualization is only possible if there is congruence between the way an individual sees themselves and their ideal self (the way they want to be or think they should be). If there is a large gap between these two concepts, negative feelings of self-worth will arise that will make it impossible for self-actualization to take place.

The environment a person is exposed to and interacts with can either frustrate or assist this natural destiny. If it is oppressive, it will frustrate; if it is favorable, it will assist.

Like a flower that will grow to its full potential if the conditions are right, but which is constrained by its environment, so people will flourish and reach their potential if their environment is good enough.

However, unlike a flower, the potential of the individual human is unique, and we are meant to develop in different ways according to our personality. Rogers believed that people are inherently good and creative.

They become destructive only when a poor self-concept or external constraints override the valuing process. Carl Rogers believed that for a person to achieve self-actualization, they must be in a state of congruence.

This means that self-actualization occurs when a person’s “ideal self” (i.e., who they would like to be) is congruent with their actual behavior (self-image).

Rogers describes an individual who is actualizing as a fully functioning person. The main determinant of whether we will become self-actualized is childhood experience.

The Fully Functioning Person

Rogers believed that every person could achieve their goal. This means that the person is in touch with the here and now, his or her subjective experiences and feelings, continually growing and changing.

In many ways, Rogers regarded the fully functioning person as an ideal and one that people do not ultimately achieve.

It is wrong to think of this as an end or completion of life’s journey; rather it is a process of always becoming and changing.

Rogers identified five characteristics of the fully functioning person:

- Open to experience : both positive and negative emotions accepted. Negative feelings are not denied, but worked through (rather than resorting to ego defense mechanisms).

- Existential living : in touch with different experiences as they occur in life, avoiding prejudging and preconceptions. Being able to live and fully appreciate the present, not always looking back to the past or forward to the future (i.e., living for the moment).

- Trust feelings : feeling, instincts, and gut-reactions are paid attention to and trusted. People’s own decisions are the right ones, and we should trust ourselves to make the right choices.

- Creativity : creative thinking and risk-taking are features of a person’s life. A person does not play safe all the time. This involves the ability to adjust and change and seek new experiences.

- Fulfilled life : a person is happy and satisfied with life, and always looking for new challenges and experiences.

For Rogers, fully functioning people are well-adjusted, well-balanced, and interesting to know. Often such people are high achievers in society.

Critics claim that the fully functioning person is a product of Western culture. In other cultures, such as Eastern cultures, the achievement of the group is valued more highly than the achievement of any one person.

Carl Rogers Quotes

The very essence of the creative is its novelty, and hence we have no standard by which to judge it. (Rogers, 1961, p. 351)

I have gradually come to one negative conclusion about the good life. It seems to me that the good life is not any fixed state. It is not, in my estimation, a state of virtue, or contentment, or nirvana, or happiness. It is not a condition in which the individual is adjusted or fulfilled or actualized. To use psychological terms, it is not a state of drive-reduction , or tension-reduction, or homeostasis. (Rogers, 1967, p. 185-186)

The good life is a process, not a state of being. It is a direction not a destination. (Rogers, 1967, p. 187)

Unconditional positive regard involves as much feeling of acceptance for the client’s expression of negative, ‘bad’, painful, fearful, defensive, abnormal feelings as for his expression of ‘good’, positive, mature, confident, social feelings, as much acceptance of ways in which he is inconsistent as of ways in which he is consistent. It means caring for the client, but not in a possessive way or in such a way as simply to satisfy the therapist’s own needs. It means a caring for the client as a separate person, with permission to have his own feelings, his own experiences’ (Rogers, 1957, p. 225)

Frequently Asked Questions

How did carl rogers’ humanistic approach differ from other psychological theories of his time.

Carl Rogers’ humanistic approach differed from other psychological theories of his time by emphasizing the importance of the individual’s subjective experience and self-perception.

Unlike behaviorism , which focused on observable behaviors, and psychoanalysis , which emphasized the unconscious mind, Rogers believed in the innate potential for personal growth and self-actualization.

His approach emphasized empathy, unconditional positive regard, and genuineness in therapeutic relationships, aiming to create a supportive and non-judgmental environment where individuals could explore and develop their true selves.

Rogers’ humanistic approach placed the individual’s subjective experience at the forefront, prioritizing their unique perspective and personal agency.

What criticisms have been raised against Carl Rogers’ humanistic approach to psychology?

Critics of Carl Rogers’ humanistic approach to psychology argue that it lacks scientific rigor and empirical evidence compared to other established theories.

Some claim that its emphasis on subjective experiences and self-perception may lead to biased interpretations and unreliable findings. Additionally, critics argue that Rogers’ approach may overlook the influence of external factors, such as social and cultural contexts, on human behavior and development.

Critics also question the universal applicability of Rogers’ theories, suggesting that they may be more relevant to certain cultural or individual contexts than others.

How has Carl Rogers’ humanistic approach influenced other areas beyond psychology?

Carl Rogers’ humanistic approach has had a significant impact beyond psychology, influencing various areas such as counseling, education, leadership, and interpersonal relationships.

In counseling, his emphasis on empathy, unconditional positive regard, and active listening has shaped person-centered therapy and other therapeutic approaches. In education, Rogers’ ideas have influenced student-centered learning, fostering a more supportive and individualized approach to teaching.

His humanistic principles have also been applied in leadership development, promoting empathetic and empowering leadership styles.

Moreover, Rogers’ emphasis on authentic communication and understanding has influenced interpersonal relationships, promoting empathy, respect, and mutual growth.

What is the current relevance of Carl Rogers’ humanistic approach in modern psychology?

Carl Rogers’ humanistic approach maintains relevance in modern psychology by emphasizing the importance of individual agency, personal growth, and the therapeutic relationship.

It continues to inform person-centered therapy and other humanistic therapeutic modalities. Rogers’ focus on empathy, acceptance, and authenticity resonates with contemporary approaches that prioritize the client’s subjective experience and self-determination.

Additionally, his ideas on the role of positive regard and the creation of a safe, non-judgmental environment have implications for various domains, including counseling, education, and interpersonal relationships.

The humanistic approach serves as a reminder of the significance of the individual’s unique perspective and the power of empathetic connections in fostering well-being and growth.

- Bozarth, J. D. (1998). Person-centred therapy: A revolutionary paradigm . Ross-on-Wye: PCCS Books

- Farber, B. A., & Doolin, E. M. (2011). Positive regard . Psychotherapy , 48 (1), 58.

- Mearns, D. (1999). Person-centred therapy with configurations of self. Counselling, 10(2), 125±130.

- Rogers, C. (1951). Client-centered therapy: Its current practice, implications and theory . London: Constable.

- Rogers, C. R. (1957). The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change . Journal of consulting psychology , 21 (2), 95.

- Rogers, C. (1959). A theory of therapy, personality and interpersonal relationships as developed in the client-centered framework. In (ed.) S. Koch, Psychology: A study of a science. Vol. 3: Formulations of the person and the social context . New York: McGraw Hill.

- Rogers, C. R. (1961). On Becoming a person: A psychotherapists view of psychotherapy . Houghton Mifflin.

- Rogers, C. R., Stevens, B., Gendlin, E. T., Shlien, J. M., & Van Dusen, W. (1967). Person to person: The problem of being human: A new trend in psychology. Lafayette, CA: Real People Press.

- Wilkins, P. (1997). Congruence and countertransference: similarities and differences. Counselling, 8(1), 36±41.

- Wilkins, P. (2000). Unconditional positive regard reconsidered . British Journal of Guidance & Counselling , 28 (1), 23-36.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

6 Humanistic and Existential Theory: Frankl, Rogers, and Maslow

This is an edited and adapted chapter by Kelland, M (2015). For full attribution see end of chapter.

HUMANISTIC AND EXISTENTIAL THEORY: VIKTOR FRANKL, CARL ROGERS, AND ABRAHAM MASLOW

Viktor frankl, existential psychology, and logotherapy, carl rogers, humanistic psychotherapy.

Abraham Maslow, Hierarchy of Needs

Viktor Frankl (1905-1997) was truly an extraordinary person. His first paper was submitted for publication by Sigmund Freud; his second paper was published at the urging of Alfred Adler. Gordon Allport was instrumental in getting Frankl’s book Man’s Search for Meaning (Frankl, 1946/1992) published in English, a book that went on to be recognized by the Library of Congress as one of the ten most influential books in America. He lectured around the world, and received some thirty honorary doctoral degrees in addition to the medical degree and the Ph.D. he had earned as a student. He was invited to a private audience with Pope Paul VI, even though Frankl was Jewish. All of this was accomplished in spite of, and partly because of, the fact that he spent several years in Nazi concentration camps during World War II, camps where his parents, brother, wife, and millions of other Jews died.

A Brief Biography of Viktor Frankl

Viktor Frankl was born in Vienna, Austria on March 26, 1905. Although his father had been forced to drop out of medical school for financial reasons, Gabriel Frankl held a series of positions with the Austrian government, working primarily with the department of child protection and youth welfare. He instilled in his son the importance of being intensely rational and having a firm sense of social justice, and Frankl became something of a perfectionist. Frankl described his mother Elsa as a kindhearted and deeply pious woman, but during his childhood she often described him as a pest, and she even changed the words of Frankl’s favorite childhood lullaby to include calling him a pest. This may have been due to the fact that Frankl was often asking questions, so much so that a family friend nicknamed him “The Thinker” (Frankl, 1995/2000). From his mother, Frankl inherited a deep emotionality. One aspect of this emotionality involved a deep attachment to his childhood home, and he often felt homesick as his responsibilities kept him away. And those responsibilities began at an early age (Frankl, 1995/2000; Pattakos, 2004).

Even in high school Frankl was developing a keen interest in existential philosophy and psychology. At the age of 16 he delivered a public lecture “On the Meaning of Life” and at 18 he wrote his graduation essay “On the Psychology of Philosophical Thought.” Throughout his high school years he maintained a correspondence with Sigmund Freud (letters that were later destroyed by the Gestapo when Frankl was deported to his first concentration camp). When Frankl was just 19, Freud submitted one of Frankl’s papers for publication in the International Journal of Psychoanalysis.

Frankl proceeded to develop his own practice and his own school of psychotherapy, known as logotherapy (the therapy of meaning, as in finding meaning in one’s life). As early as 1929, Frankl had begun to recognize three possible ways to find meaning in life: a deed we do or a work we create; a meaningful human encounter, particularly one involving love; and choosing one’s attitude in the face of unavoidable suffering. Logotherapy eventually became known as the third school of Viennese psychotherapy, after Freud’s psychoanalysis and Adler’s individual psychology. During the 1930s Frankl did much of his work with suicidal patients and teenagers. He had extensive talks with Wilhelm Reich in Berlin, who was also involved in youth counseling by that time. As the 1930s came to an end, and Austria had been taken over by the Nazis, Frankl sought a visa to emigrate to the United States, which was eventually granted. However, Frankl’s parents could not get a visa, so he chose to remain in Austria with them. He also began work on his first book, eventually published in English under the title The Doctor and the Soul (Frankl, 1946/1986), which provided the foundation for logotherapy. He fell in love with Tilly Grosser, and they were married in 1941, the last legal Jewish marriage in Vienna under the Nazis.

Shortly thereafter, the realities of Nazi Germany overcame what little privilege Frankl had enjoyed as a doctor at a major hospital. Since it was illegal for Jews to have children, Tilly Frankl was forced to abort their first child. Frankl later dedicated The Unheard Cry for Meaning “To Harry or Marion an unborn child” (Frankl, 1978). Then the entire Frankl family, except for his sister who had gone to Australia, was deported to the Theresienstadt concentration camp (the same camp from which Anna Freud cared for orphans after the war). As they marched into the camp with hundreds, perhaps thousands, of other prisoners, his father tried to calm those who panicked by saying again and again: “Be of good cheer, for God is near.” Frankl’s parents, his only brother, and his wife Tilly died in the concentration camps. Most tragically, Frankl believed that his wife died after the war, but before the liberating Allied forces could care for all of the many, many suffering people (Frankl, 1995/2000).

When Frankl was deported, he tried to hide and save his only copy of The Doctor and the Soul by sewing it into the lining of his coat. However, he was forced to trade his good coat for an old one, and the manuscript was lost. While imprisoned, he managed to obtain a few scraps of paper on which to make notes. Those notes later helped him to recreate his book, and that goal gave such meaning to his life that he considered it an important factor in his will to survive the horrors of the concentration camps. It would be difficult to adequately describe the conditions of the concentration camps, or how they affected the minds of those imprisoned, especially since the effects were quite varied. Frankl describes those conditions in Man’s Search for Meaning. The book is rather short, but its contents are deep beyond comprehension. Frankl himself, however, might take exception to referring to his book as “deep.” Depth psychology was a term used for psychodynamically-oriented psychology. In 1938 Frankl coined the term “height psychology” in order to supplement, but not replace, depth psychology (Frankl, 1978).

After the war, Frankl’s life was nothing less than amazing. He returned to his home city of Vienna, married Eleonore Katharina, née Schwindt, and raised a daughter named Gabriele, whose husband and the Frankl’s grandchildren all lived in Vienna. He lectured around the world, received many honors, wrote numerous books, all while continuing to practice psychiatry and teach at the University of Vienna, Harvard, and elsewhere. He had a great interest in humor and in cartooning. Throughout his life, Frankl steadfastly refused to acknowledge the validity of collective guilt toward the German people. When asked repeatedly how he could return to Vienna, after all that happened to him and his family, Frankl replied:

…I answered with a counter-question: “Who did what to me?” There had been a Catholic baroness who risked her life by hiding my cousin for years in her apartment. There had been a Socialist attorney (Bruno Pitterman, later vice chancellor of Austria), who knew me only casually and for whom I had never done anything; and it was he who smuggled some food to me whenever he could. For what reason, then, should I turn my back on Vienna? (pp. 101-102; Frankl, 1995/2000)

Viktor Frankl died peacefully on September 2, 1997. He was 92 years old. During his life, his work influenced many people, from the ordinary to the famous and influential. “Viktor Frankl, to be sure, leaves a profound legacy” (pg. 24; Pattakos, 2004).

The Theoretical Basis for Logotherapy

The word logos is Greek for “meaning,” and this third Viennese school of psychotherapy focuses on the meaning of human existence and man’s search for such a meaning. Logotherapy, therefore, focuses on person’s will-to-meaning, in contrast to Freud’s will-to-pleasure (the drive to satisfy the desires of the id, the pleasure principle) or Adler’s will-to-power (the drive to overcome inferiority and attain superiority; adopted from Nietzsche) (Frankl, 1946/1986, 1946/1992).

The will-to-meaning is, according to Frankl, the primary source of one’s motivation in life. It is not a secondary rationalization of the instinctual drives, and meaning and values are not simply defense mechanisms. As Frankl eloquently points out:

…as for myself, I would not be willing to live merely for the sake of my “defense mechanisms,” nor would I be ready to die merely for the sake of my “reaction formations.” Man, however, is able to live and even to die for the sake of his ideals and values! (pg. 105; Frankl, 1946/1992)

Unfortunately, one’s search for meaning can be frustrated. This existential frustration can lead to what Frankl identified as a noogenic neurosis (a neurosis of the mind or, in other words, the specifically human dimension). Frankl suggested that when neuroses arise from an individual’s inability to find meaning in their life, what they need is logotherapy, not psychotherapy. More specifically, they need help to find some meaning in their life, some reason to be. It would be safe to say that many of us find it difficult to find meaning in our own lives, and research has indeed shown that the will-to-meaning is a significant concern throughout the world (Frankl, 1946/1992). In order to make sense of this problem, Frankl has suggested that we should not ask what we expect from life, but rather, we should understand that life expects something from us:

A colleague, an aged general practitioner, turned to me because he could not come to terms with the loss of his wife, who had died two years before. His marriage had been very happy, and he was now extremely depressed. I asked him quite simply: “Tell me what would have happened if you had died first and your wife had survived you?” “That would have been terrible,” he said. “How my wife would have suffered?” “Well, you see,” I answered, “your wife has been spared that, and it was you who spared her, though of course you must now pay by surviving and mourning her.” In that very moment his mourning had been given a meaning – the meaning of a sacrifice. (pg. xx; Frankl, 1946/1986)

The latter point brings us back to Frankl’s discussion of how one can find meaning in life: through creating a work or doing a deed; by experiencing something or encountering someone, particularly when love is involved; or by choosing one’s attitude toward unavoidable suffering. Those of us who have lost someone dear know how easily it leads to deep suffering. Frankl had already written the first version of The Doctor and the Soul when he entered the Theresienstadt concentration camp, so his views on how one should choose their attitude toward unavoidable suffering were put to a test that no research protocol could ever hope to achieve! His observations form the basis for much of Man’s Search for Meaning. Both his observations of others and his own reactions in this unimaginably horrible and tragic situation are quite fascinating:

…as we stumbled on for miles, slipping on icy spots, supporting each other time and again, dragging one another up and onward, nothing was said, but we both knew: each of was thinking his wife…my mind clung to my wife’s image…Real or not, her look was then more luminous than the sun…A thought transfixed me: for the first time in my life I saw the truth as it is set into song by so many poets, proclaimed as the final wisdom by so many thinkers. The truth – that love is the ultimate and the highest goal to which man can aspire. Then I grasped the meaning of the greatest secret that human poetry and human thought and belief have to impart: The salvation of man is through love and in love. (pp. 48-49; Frankl, 1946/1992)

…One evening, when we were already resting on the floor of our hut, dead tired, soup bowls in hand, a fellow prisoner rushed in and asked us to run out to the assembly grounds and see the wonderful sunset. Standing outside we saw sinister clouds glowing in the west and the whole sky alive with clouds of ever-changing shapes and colors, from steel blue to blood red…Then, after minutes of moving silence, one prisoner said to another, “How beautiful the world could be!” (pg. 51; Frankl, 1946/1992)

…The experiences of camp life show that man does have a choice of action. There were enough examples, often of a heroic nature, which proved that apathy could be overcome, irritability suppressed. Man can preserve a vestige of spiritual freedom, of independence of mind, even in such terrible conditions of psychic and physical stress.

We who lived in concentration camps can remember the men who walked through the huts comforting others, giving away their last piece of bread. They may have been few in number, but they offer sufficient proof that everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms – to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way. (pp. 74-75; Frankl, 1946/1992)

Discussion Question: Frankl considered the most important aspect of survival to be the ability to find meaning in one’s life. Have you found meaning in your life? Are there goals you have that you believe might add meaning to your life? Do you know anyone personally whose life seems to be filled with meaning, and if so, how does it appear to affect them?

Logotherapy as a Technique

As a technique, logotherapy (Frankl, 1946/1986, 1946/1992) is based on a simple trap in which neurotic individuals often find themselves. When a person thinks about or approaches a situation that provokes a neurotic symptom, such as fear, the person experiences anticipatory anxiety. This anticipatory anxiety takes the form of the symptom, which reinforces their anxiety. And so on… In order to help people break out of this negative cycle, Frankl recommends having them focus intently on the very thing that evokes their symptoms, even trying to exhibit their symptoms more severely than ever before! As a result, the patient is able to separate themselves from their own neurosis, and eventually the neurosis loses its potency. In some ways this is similar to modern day exposure therapy for trauma and anxiety, where a client is progressively exposed to the things they fear or anxiously anticipate, and clients learn gradual desensitization to what they fear or avoid.

Real life Application Example of Frankl’s Work

In 1989, Stephen Covey published The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. Covey’s book became perhaps the best selling business book in history, selling millions of copies and still in use today in many business schools and on many of the “best reads” lists on Amazon or Goodreads. Covey, a devout practicing Mormon (Latter Day Saints) and influenced by his faith, presents a very existential approach to understanding our lives, particularly with regard to the problems we experience every day. Perhaps it should not be surprising, then, that in the chapters describing the first two of these seven habits he cites and quotes Viktor Frankl numerous times. Indeed, Covey cites Frankl’s first two books as being profoundly influential in his own life, and how impressed Covey was having met Frankl shortly before Frankl’s death (see Covey’s foreword in Pattakos, 2004).

The first two habits, according to Covey, are: 1) be proactive, and 2) begin with the end in mind. He briefly describes Frankl’s experiences in the concentration camps, and refers to Frankl’s most widely quoted saying, that Frankl himself could decide how his experiences would affect him, and that no one could take that freedom away from Frankl! People who choose to develop this level of personal freedom are certainly being proactive, as opposed to responding passively to events that occur around them and to them. It is not necessary, of course, to suffer such tragic circumstances in order to become proactive in one’s own life:

…It is in the ordinary events of every day that we develop the proactive capacity to handle the extraordinary pressures of life. It’s how we make and keep commitments, how we handle a traffic jam, how we respond to an irate customer or a disobedient child. It’s how we view our problems and where we focus our energies. It’s the language we use. (pg. 92; Covey, 1989)

Covey compares his habit of beginning with the end in mind to logotherapy, helping people to recognize the meaning that their life holds. Covey works primarily in business leadership training, so the value of working toward a greater goal than simply keeping a company in business from day to day is clear, especially for those who care about employee morale and quality control (see also Principle-Centered Leadership; Covey, 1990). When employees share a sense of purpose in their work, they are likely to have higher intrinsic motivation. Think about it for a moment. Have you ever had a job you didn’t really understand, and didn’t care about? Have you ever been given that sort of homework in school or college? So, how much effort did you really put into that job or assignment?

Covey’s remaining habits are: 3) put first things first, 4) think win/win, 5) seek first to understand, then to be understood, 6) synergize, and 7) sharpen the saw. At first glance these principles seem reasonably straight forward, emphasizing practical and responsible actions. However, what does “sharpen the saw” mean? Sharpening the saw refers to keeping our tools in good working order, and we are our most important tool. Covey considers it essential to regularly and consistently, in wise and balanced ways, to exercise the four dimensions of our nature: physical, mental, social/emotional, and spiritual. By investing in ourselves, we are taking care to live an authentic life.

Covey, 2004 published a book about the “eighth habit”. He said that this was not simply an important habit he had overlooked before, but one that has risen to new significance as we have fully entered the age of information and technology in the twenty-first century. As communication has become much easier (e.g., email), it has also become less personal and meaningful. Thus the need for the eighth habit: find your voice and inspire others to find theirs. According to Covey, “ voice is unique personal significance .” Essentially, it is the same as finding meaning in one’s life, and then helping others to find meaning in their own lives. It is through finding a mission or a purpose in life that we can move “from effectiveness to greatness” (Covey, 2004).

Frankl, Covery, and other humanist theorists have suggested is is less a matter of what our specific job might be, it is the work we do that represents who we are. When we meet our work with enthusiasm, appreciation, generosity, and integrity, we meet it with meaning. And no matter how mundane a job might seem at the time, we can transform it with meaning. Meaning is life’s legacy, and it is as available to us at work as it is available to us in our deepest spiritual quests. We breathe, therefore we are – spiritual. Life is; therefore it is – meaningful. We do, therefore we work.

Viktor Frankl’s legacy was one of hope and possibility. He saw the human condition at its worst, and human beings behaving in ways intolerable to the imagination. He also saw human beings rising to heights of compassion and caring in ways that can only be described as miraculous acts of unselfishness and transcendence. There is something in us that can rise above and beyond everything we think possible… (pg. 162; Pattakos, 2004)

Video of Carl Rogers Interviewing a Client named Gloria -notice how Rogers focuses deeply on her experience, and each question he asks tries to deepen her own understanding of her experience. At the same time he presents an unconditional regard for her story.

Placing Rogers in Context: A Psychology 2,600 Years in the Making

Carl Rogers was an extraordinary individual whose approach to psychology emphasized individuality. Raised with a strong Christian faith, exposed to Eastern culture and spirituality in college, and then employed as a therapist for children, he came to value and respect each person he met. Because of that respect for the ability of each person to grow, and the belief that we are innately driven toward actualization, Rogers began the distinctly humanistic approach to psychotherapy that became known as client-centered therapy .

Taken together, client-centered therapy and self-actualization offer a far more positive approach to fostering the growth of each person than most other disciplines in psychology. Unlike the existing approaches of psychoanalysis, which aimed to uncover problems from the past, or behavior therapies, which aimed to identify problem behaviors and control or “fix” them, client-centered therapy grew out of Rogers’ simple desire to help his clients move forward in their lives. Indeed, he had been trained as a psychoanalyst, but Rogers found the techniques unsatisfying, both in their goals and their ability to help the children he was working with at the time. The seemingly hands-off approach of client-centered therapy fit well with a Taoist perspective, something Rogers had studied, discussed, and debated during his trip to China. In A Way of Being, Rogers (1980) quotes an ancient philosopher Lao Tsu, where he says Lao Tsu sums up many of his deeper beliefs:

If I keep from meddling with people, they take care of themselves,

If I keep from commanding people, they behave themselves,

If I keep from preaching at people, they improve themselves, If I keep from imposing on people, they become themselves.

Lao Tsu, c600 B.C.

Rogers, like Maslow, wanted to see psychology contribute far more to society than merely helping individuals with psychological distress. He extended his sincere desire to help people learn to really communicate, with empathic understanding, to efforts aimed at bringing peace to the world. On the day he died, he had just been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize. Since a Nobel Prize cannot be awarded to someone who has died, he was not eligible to be nominated again. If he had lived a few more years, he may well have received that award. His later years were certainly committed to peace in a way that deserved such recognition.

Basic Concepts

Rogers believed that each of us lives in a constantly changing private world, which he called the experiential field. Everyone exists at the center of their own experiential field, and that field can only be fully understood from the perspective of the individual. This concept has a number of important implications. The individual’s behavior must be understood as a reaction to their experience and perception of the field. They react to it as an organized whole, and it is their reality. The problem this presents for the therapist is that only the individual can really understand their experiential field. This is quite different than the Freudian perspective, in which only the trained and objective psychoanalyst can break through the defense mechanisms and understand the basis of the patient’s unconscious impulses. One’s perception of the experiential field is limited, however. Rogers believed that certain impulses, or sensations, can only enter into the conscious field of experience under certain circumstances. Thus, the experiential field is not a true reality, but rather an individual’s potential reality (Rogers, 1951).

The one basic tendency and striving of the individual is to actualize, maintain, and enhance the experiencing of the individual or, in other words, an actualizing tendency. Rogers borrowed the term self-actualization, a term first used by Kurt Goldstein, to describe this basic striving.

For Rogers, self-actualization was a tendency to move forward, toward greater maturity and independence, or self-responsibility. This development occurs throughout life, both biologically (the differentiation of a fertilized egg into the many organ systems of the body) and psychologically (self-government, self-regulation, socialization, even to the point of choosing life goals).

The ability of individuals to make the choices necessary for actualizing their self and to then fulfill those choices is what Rogers called personal power (Rogers, 1977). He believed there are many self-actualized individuals revolutionizing the world by trusting their own power, without feeling a need to have “power over” others. They are also willing to foster the latent actualizing tendency in others. We can easily see the influence of Alfred Adler here, both in terms of the creative power of the individual and seeking superiority within a healthy context of social interest. Client-centered therapy was based on making the context of personal power a clear strategy in the therapeutic relationship:

…the client-centered approach is a conscious renunciation and avoidance by the therapist of all control over, or decision-making for, the client. It is the facilitation of self-ownership by the client and the strategies by which this can be achieved…based on the premise that the human being is basically a trustworthy organism, capable of…making constructive choices as to the next steps in life, and acting on those choices. (pp. 14-15; Rogers, 1977)

Discussion Question: Rogers claimed that no one can really understand your experiential field. Would you agree, or do you sometimes find that close friends or family members seem to understand you better than you understand yourself? Are these relationships congruent?

Personality Development

Although Rogers described personality within the therapist-client relationship, the focus of his therapeutic approach was based on how he believed the person had arrived at a point in their life where they were suffering from psychological distress. Therefore, the same issues apply to personality development as in therapy. A very important aspect of personality development, according to Rogers, is the parent-child relationship. The nature of that relationship, and whether it fosters self-actualization or impedes personal growth, determines the nature of the individual’s personality and, consequently, their self-structure and psychological adjustment.

A child begins life with an actualizing tendency. As they experience life, and perceive the world around them, they may be supported in all things by those who care for them, or they may only be supported under certain conditions (e.g., if their behavior complies with strict rules). As the child becomes self-aware, it develops a need for positive regard. When the parents offer the child unconditional positive regard , the child continues moving forward in concert with its actualizing tendency. So, when there is no discrepancy between the child’s self-regard and its positive regard (from the parents), the child will grow up psychologically healthy and well-adjusted. However, if the parents offer only conditional positive regard, if they only support the child according the desires and rules of the parents, the child will develop conditions of worth. As a result of these conditions of worth, the child will begin to perceive their world selectively; they will avoid those experiences that do not fit with its goal of obtaining positive regard. The child will begin to live the life of those who set the conditions of worth, rather than living its own life.

As the child grows older, and more aware of its own condition in the world, their behavior will either fit within their own self-structure or not. If they have received unconditional positive regard, such that their self-regard and positive regard are closely matched, they will experience congruence . In other words, their sense of self and their experiences in life will fit together , and the child will be relatively happy and well-adjusted. But, if their sense of self and their ability to obtain positive regard do not match, the child will develop incongruence. Consider, for example, children playing sports. That alone tells us that parents have established guidelines within which the children are expected to “play.” Then we have some children who are naturally athletic, and other children who are more awkward and/or clumsy. They may become quite athletic later in life, or not, but during childhood there are many different levels of ability as they grow. If a parent expects their child to be the best player on the team, but the child simply isn’t athletic, how does the parent react? Do they support the child and encourage them to have fun, or do they pressure the child to perform better and belittle them when they can’t? Children are very good at recognizing who the better athletes are, and they know their place in the hierarchy of athletics, i.e., their athletic self-structure. So if a parent demands dominance from a child who knows they just aren’t that good, the child will develop incongruence. Rogers believed, quite understandably, that such conditions are threatening to a child, and will activate defense mechanisms. Over time, however, excessive or sudden and dramatic incongruence can lead to the breakdown and disorganization of the self-structure. As a result, the individual is likely to experience psychological distress that will continue throughout life (Rogers, 1959/1989).

Discussion Question: Conditions of worth are typically first established in childhood, based on the relationship between a child and his or her parents. Think about your relationship with your own parents and, if you have children, think about how you treat them. Are most of the examples that come to mind unconditional positive regard, or conditional positive regard? How has that affected your relationship with your parents and/or your own children?

What about individuals who have developed congruence, having received unconditional positive regard throughout development or having experienced successful client-centered therapy? They become, according to Rogers (1961), a fully functioning person. He also said they lead a good life. The good life is a process, not a state of being, and a direction, not a destination. It requires psychological freedom, and is the natural consequence of being psychologically free to begin with. Whether or not it develops naturally, thanks to a healthy and supportive environment in the home, or comes about as a result of successful therapy, there are certain characteristics of this process. The fully functioning person is increasingly open to new experiences, they live fully in each moment, and they trust themselves more and more. They become more able and more willing to experience all of their feelings, they are creative, they trust human nature, and they experience the richness of life. The fully functioning person is not simply content, or happy, they are alive:

The Hierarchy of Needs

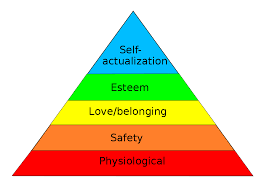

Abraham Maslow is a personality theorist who is undoubtedly best known for his hierarchy of needs. Although Maslow did not develop the commonly viewed triangle of needs, this image has become iconic for the view of the hierarchy of human needs. Developed within the context of a theory of human motivation, Maslow believed that human behavior is driven and guided by a set of basic needs: physiological needs, safety needs, belongingness and love needs, esteem needs, and the need for self-actualization. It is generally accepted that individuals must move through the hierarchy in order, satisfying the needs at each level before one can move on to a higher level. The reason for this is that lower needs tend to occupy the mind if they remain unsatisfied . How easy is it to work or study when you are really hungry or thirsty? But Maslow did not consider the hierarchy to be rigid. For example, he encountered some people for whom self-esteem was more important than love, individuals suffering from antisocial personality disorder seem to have a permanent loss of the need for love, or if a need has been satisfied for a long time it may become less important. As lower needs are becoming satisfied, though not yet fully satisfied, higher needs may begin to present themselves. And of course there are sometimes multiple determinants of behavior, making the relationship between a given behavior and a basic need difficult to identify (Maslow, 1943/1973; Maslow, 1970).

The physiological needs are based, in part, on the concept of homeostasis, the natural tendency of the body to maintain critical biological levels of essential elements or conditions, such as water, salt, energy, and body temperature. Sexual activity, though not essential for the individual, is biologically necessary for the human species to survive. Maslow described the physiological needs as the most prepotent. In other words, if a person is lacking everything in life, having failed to satisfy physiological, safety, belongingness and love, and esteem needs, their consciousness will most like be consumed with their desire for food and water. As the lowest and most clearly biological of the needs, these are also the most animal-like of our behavior. In Western culture, however, it is rare to find someone who is actually starving. So when we talk about being hungry, we are really talking about an appetite, rather than real hunger (Maslow, 1943/1973; Maslow, 1970). Many Americans are fascinated by stories such as those of the ill-fated Donner party, trapped in the Sierra Nevada mountains during the winter of 1846-1847, and the Uruguayan soccer team whose plane crashed in the Andes mountains in 1972. In each case, either some or all of the survivors were forced to cannibalize those who had died. As shocking as such stories are, they demonstrate just how powerful our physiological needs can be.

The safety needs can easily be seen in young children. They are easily startled or frightened by loud noises, flashing lights, and rough handling. They can become quite upset when other family members are fighting, since it disrupts the feeling of safety usually associated with the home. According to Maslow, many adult neurotics are like children who do not feel safe. From another perspective, that of Erik Erikson, children and adults raised in such an environment do not trust the environment to provide for their needs. Although it can be argued that few people in America seriously suffer from a lack of satisfying physiological needs, there are many people who live unsafe lives. For example, inner city crime, abusive spouses and parents, incurable diseases, all present life threatening dangers to many people on a daily basis.

Throughout the evolution of the human species we found safety primarily within our family, tribal group, or our community. It was within those groups that we shared the hunting and gathering that provided food. Once the physiological and safety needs have been fairly well satisfied, according to Maslow, “the person will feel keenly, as never before, the absence of friends, or a sweetheart, or a wife, or children” (Maslow, 1970). Most notable among personality theorists who addressed this issue was Wilhelm Reich. An important aspect of love and affection is sex. Although sex is often considered a physiological need, given its role in procreation, sex is what Maslow referred to as a multidetermined behavior. In other words, it serves both a physiological role (procreation) and a belongingness/love role (the tenderness and/or passion of the physical side of love). Maslow was also careful to point out that love needs involve both giving and receiving love in order for them to be fully satisfied (Maslow, 1943/1973; Maslow, 1970).

Maslow believed that all people desire a stable and firmly based high evaluation of themselves and others (at least the others who comprise their close relationships). This need for self-esteem, or self-respect, involves two components. First is the desire to feel competent, strong, and successful (similar to Bandura’s self-efficacy). Second is the need for prestige or status, which can range from simple recognition to fame and glory. Maslow credited Adler for addressing this human need, but felt that Freud had neglected it. Maslow also believed that the need for self-esteem was becoming a central issue in therapy for many psychotherapists. However, as we saw in Chapter 12, Albert Ellis considers self-esteem to be a sickness. Ellis’ concern is that self-esteem, including efforts to boost self-esteem in therapy, requires that people rate themselves, something that Ellis felt will eventually lead to a negative evaluation (no one is perfect!). Maslow did acknowledge that the healthiest self-esteem is based on well-earned and deserved respect from others, rather than fleeting fame or celebrity status (Maslow, 1943/1973; Maslow, 1970).

When all of these lower needs (physiological, safety, belongingness and love, and esteem) have been largely satisfied, we may still feel restless and discontented unless we are doing what is right for ourselves. “What a man can be, he must be” (pg. 46; Maslow, 1970). Thus, the need for self-actualization, which Maslow described as the highest of the basic needs, can also be referred to as a Being-need , as opposed to the lower deficiency-needs (Maslow, 1968). We will examine self-actualization in more detail in the following section.

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is based on a theory of motivation. Individuals must essentially satisfy the lower deficiency needs before they become focused on satisfying the higher Being needs. Beyond even the Being needs there is something more, a state of transcendence that ties all people and the whole of creation together.

Although Maslow recognized that humans share basic drives with other animals. We get hungry, even though how and what we eat is determined culturally. We need to be safe, like any other animal, but again we seek and maintain our safety in different ways (such as having a police force to provide safety for us). Given our fundamental similarity to other animals, therefore, Maslow referred to the basic needs as instinctoid . The lower the need the more animal-like it is, the higher the need, the more human it is, and self-actualization was, in Maslow’s opinion, uniquely human (Maslow, 1970).

There are also classic studies on the importance of environmental enrichment on the structural development of the brain itself (Diamond et al., 1975; Globus, et al., 1973; Greenough & Volkmar, 1973; Rosenzweig, 1984; Spinelli & Jensen, 1979; Spinelli, Jensen, & DiPrisco, 1980). Even less is known about the aesthetic needs, but Maslow was convinced that some people need to experience, indeed they crave, beauty in their world. Ancient cave drawings have been found that seem to serve no other purpose than being art. The cognitive and aesthetic needs may very well have been fundamental to our evolution as modern humans.

Self-Actualization

Maslow began his studies on self-actualization in order to satisfy his own curiosity about people who seemed to be fulfilling their unique potential as individuals. He did not intend to undertake a formal research project, but he was so impressed by his results that he felt compelled to report his findings. Amongst people he knew personally and public and historical figures, he looked for individuals who appeared to have made full use of their talents, capacities, and potentialities. In other words, “people who have developed or are developing to the full stature of which they are capable” (Maslow, 1970). His list of those who clearly seemed self-actualized included Abraham Lincoln, Thomas Jefferson, Albert Einstein, Eleanor Roosevelt, Jane Addams, William James, Albert Schweitzer, Aldous Huxley, and Baruch Spinoza. His list of individuals who were most-likely self-actualized included Goethe (possibly the great-grandfather of Carl Jung), George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Harriet Tubman (born into slavery, she became a conductor on the Underground Railroad prior to the Civil War), and George Washington Carver (born into slavery at the end of the Civil War, he became an agricultural chemist and prolific inventor). In addition to the positive attributes listed above, Maslow also considered it very important that there be no evidence of psychopathology in those he chose to study. After comparing the seemingly self-actualized individuals to people who did not seem to have fulfilled their lives, Maslow identified fourteen characteristics of self-actualizing people (Maslow, 1950/1973, 1970), as follows:

Maslow had something else interesting to say about self-actualization in The Farther Reaches of Human Nature: “What does self-actualization mean in moment-to-moment terms? What does it mean on Tuesday at four o’clock?” (pg. 41). Consequently, he offered a preliminary suggestion for an operational definition of the process by which self-actualization occurs. In other words, what are the behaviors exhibited by people on the path toward fulfilling or achieving the fourteen characteristics of self-actualized people described above? Sadly, this could only remain a preliminary description, i.e., they are “ideas that are in midstream rather than ready for formulation into a final version,” because this book was published after Maslow’s death (having been put together before his sudden and unexpected heart attack).

What does one do when he self-actualizes? Does he grit his teeth and squeeze? What does self-actualization mean in terms of actual behavior, actual procedure? I shall describe eight ways in which one self-actualizes. (pg. 45; Maslow, 1971)

They experience full, vivid, and selfless concentration and total absorption. Within the ongoing process of self-actualization, they make growth choices (rather than fear choices; progressive choices rather than regressive choices) They are aware that there is a self to be actualized.

When in doubt, they choose to be honest rather than dishonest. They trust their own judgment, even if it means being different or unpopular (being courageous is another version of this behavior). They put in the effort necessary to improve themselves, working regularly toward self-development no matter how arduous or demanding . They embrace the occurrence of peak experiences, doing what they can to facilitate and enjoy more of them (as opposed to denying these experiences as many people do). They identify and set aside their ego defenses (they have “the courage to give them up”). Although this requires that they face up to painful experiences, it is more beneficial than the consequences of defenses such as repression.

Connections Across Cultures: Is Nothing Sacred?

Maslow described some lofty ambitions for humanity in Toward a Psychology of Being (1968) and The Farther Reaches of Human Nature (1971), as well as some challenges we face along the way. Transcendence, according to Maslow, is a loss of our sense of Self, as we begin to feel an intimate connection with the world around us and all other people. But transcendence is exceedingly difficult when we are hindered by the defense mechanism of desacralization. What exactly does the word “sacred” mean? A dictionary definition of sacred says that it is “connected with God (or the gods) or dedicated to a religious purpose and so deserving veneration.” However, there is another definition that does not require a religious context: “regarded with great respect and reverence by a particular religion, group, or individual” (The Oxford American College Dictionary, 2002). Maslow described desacralization as a rejection of the values and virtues of one’s parents. As a result, people grow up without the ability to see anything as sacred, eternal, or symbolic. In other words, they grow up without meaning in their lives.

The process of resacralization , which Maslow considered an essential task of therapists working with clients who seek help in this critical area of their life, requires that we have some concept of what is sacred. So, what is sacred? Many answers can be found, but there does seem to be at least one common thread.

…Compassion is the wish that others be free of suffering. It is by means of compassion that we aspire to attain enlightenment. It is compassion that inspires us to engage in the virtuous practices that lead to Buddhahood. We must therefore devote ourselves to developing compassion. The Dalai Lama (2001)

I have been engaged in peace work for more than thirty years: combating poverty, ignorance, and disease; going to sea to help rescue boat people; evacuating the wounded from combat zones; resettling refugees; helping hungry children and orphans; opposing wars; producing and disseminating peace literature; training peace and social workers; and rebuilding villages destroyed by bombs. It is because of the practice of meditation – stopping, calming, and looking deeply – that I have been able to nourish and protect the sources of my spiritual energy and continue this work.

Thich Nhat Hanh (1995)

…Our progress is the penetrating of the present moment, living life with our feet on the ground, living in compassionate, active relationship with others, and yet living in the awareness that life has been penetrated by the eternal moment of God and unfolds in the power of that moment.

Fr. Laurence Freeman (1986)

Keep your hands busy with your duties in this world, and your heart busy with God.

Sheikh Muzaffer (cited in Essential Sufism by Fadiman & Frager, 1997) Forgiveness is a letting go of past suffering and betrayal, a release of the burden of pain and hate that we carry. Forgiveness honors the heart’s greatest dignity. Whenever we are lost, it brings us back to the ground of love. Jack Kornfield (2002) And he said to him, “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind. This is the great and first commandment. And a second is like it, You shall love your neighbor as yourself…” Jesus Christ (The Holy Bible, 1962)

Christians, Buddhists, Muslims, as well as members of other religions and humanists, all have some variation of what has been called The Golden Rule: treating others as you would like to be treated. If that is sacred, then even amongst atheists, young people can evaluate the values and virtues of their parents, community, and culture, and then decide whether those values are right or wrong, whether they want to perpetuate an aspect of that society based on their own thoughts and feelings about how they, themselves, may be treated someday by others. This resacralization need not be religious or spiritual, but it commonly is, and some psychologists are comfortable embracing spirituality as such.

Kenneth Pargament and Annette Mahoney (2005) wrote a chapter entitled Spirituality: Discovering and Conserving the Sacred, which was included in the Handbook of Positive Psychology (Snyder & Lopez, 2005). First, they point out that religion is an undeniable fact in American society. Some 95 percent of Americans believe in God, and 86 percent believe that He can be reached through prayer and that He is important or very important to them. Spirituality, according to Pargament and Mahoney, is the process in which individuals seek both to discover and to conserve that which is sacred. It is interesting to note that Maslow and Rogers consider self-actualization and transcendence to be a process as well, not something that one can get and keep permanently. An important aspect of defining what is sacred is that it is imbued with divinity. God may be seen as manifest in marriage, work can be seen as a vocation to which the person is called, the environment can been seen as God’s creation. In each of these situations, and in others, what is viewed as sacred has been sanctified by those who consider it sacred. Unfortunately, this can have negative results as well, such as when the Heaven’s Gate cult followed their sanctified leader to their deaths. Thus, spirituality is not necessarily synonymous with a good and healthy lifestyle.

Still, there is research that has shown that couples who sanctify their marriage (decide their marriage is sacred and important) experience greater marital satisfaction, less marital conflict, and more effective marital problem-solving strategies. Likewise, mothers and fathers who sanctify the role of parenting report less aggression and more consistent discipline in raising their children. For college students, spiritual striving was more highly correlated with well-being than any other form of goal-setting (see Pargament & Mahoney, 2005). So there appear to be real psychological advantages to spiritual pursuits. This may be particularly true during challenging times in our lives:

…there are aspects of our lives that are beyond our control. Birth, developmental transitions, accidents, illnesses, and death are immutable elements of existence. Try as we might to affect these elements, a significant portion of our lives remains beyond our immediate control. In spirituality, however, we can find ways to understand and deal with our fundamental human insufficiency, the fact that there are limits to our control… (pg. 655; Pargament & Mahoney, 2005)

Vocabulary and Concepts

Congruence: Carl Rogers believed that for a person to achieve self-actualization they must be in a state of congruence. This means that self-actualization occurs when a person’s “ideal self” (i.e., who they would like to be) is congruent with their actual behavior (self-image).

Hierarchy of Needs: Maslow believed that human behavior is driven and guided by a set of basic needs: physiological needs, safety needs, belongingness and love needs, esteem needs, and the need for self-actualization. It is generally accepted that individuals must move through the hierarchy in order, satisfying the needs at each level before one can move on to a higher level.

Logotherapy : the therapy of meaning, as in finding meaning in one’s life.

Personal Power: Rogers defined this as the ability of individuals to make the choices necessary for actualizing their self and to then fulfill those choices.

Resacralization: the process of deciding what is sacred and treating certain things as sacred and important. Maslow felt this was very important and what we found sacred should guide our life, similar to Stephen Covey’s idea of “put the end in mind” by which he meant to follow what was most important and sacred to a person.

Self-Actualization: Maslow described self-actualization as the highest of the basic needs, or the Being-need. Maslow felt these were needs related to meaning, and doing or experiencing personally meaningful things in life.

Will-to-Meaning: Viktor Frankl believed this was the primary motivator in life, and his therapy called logotherapy helped people find meaningfulness in life.

Unconditional Positive Regard : According to Rogers, unconditional positive regard involves showing complete support and acceptance of a person no matter what that person says or does. Therapists can do this, and parents and friends can do this. People can still have boundaries and say yes and no, but an overall attitude of acceptance from a parent or friend or therapist Roger’s thought was a great gift.

Quiz: Choose the theorist that best matches the concept they emphasized. Drag the concept on to the theorists name.

For references, please see the end of this book under the References for chapters 5 and 6 section.

This chapter is an edited and adapted version of an open textbook available by Mark Kelland. The original authors bear no responsibility for this chapter. The original chapter can be found here: Mark Kelland , Personality Theory in a Cultural Context. OpenStax CNX. Nov 4, 2015 http://cnx.org/contents/[email protected].

Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike

The Balance of Personality Copyright © 2020 by Chris Allen is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- When did science begin?

- Where was science invented?

humanistic psychology

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Simply Psychology - Humanistic Approach in Psychology (humanism): Definition and Examples

- Verywell Mind - What is Humanistic Psychology?

humanistic psychology , a movement in psychology supporting the belief that humans, as individuals, are unique beings and should be recognized and treated as such by psychologists and psychiatrists. The movement grew in opposition to the two mainstream 20th-century trends in psychology, behaviourism and psychoanalysis . Humanistic principles attained application during the “human potential” movement, which became popular in the United States during the 1960s.

Humanistic psychologists believe that behaviourists are overconcerned with the scientific study and analysis of the actions of people as organisms (to the neglect of basic aspects of people as feeling, thinking individuals) and that too much effort is spent in laboratory research—a practice that quantifies and reduces human behaviour to its elements. Humanists also take issue with the deterministic orientation of psychoanalysis, which postulates that one’s early experiences and drives determine one’s behaviour. The humanist is concerned with the fullest growth of the individual in the areas of love , fulfillment, self-worth, and autonomy .