- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Teaching Expertise

- Classroom Ideas

- Teacher’s Life

- Deals & Shopping

- Privacy Policy

22 Motivation Activity Ideas for Students

March 7, 2023 // by Dominique Binns

Keeping your students engaged and motivated can be challenging! Making learning fun and intriguing sometimes requires creative lesson planning that utilizes positive psychology to decrease the effects of stress that can impede a child’s learning experience. By curating a lesson plan that makes room for student motivation, you’ll witness the positive effects of happier students. From cutting down study time to unlocking better results, motivation activity ideas will benefit both you and your students! Take a look at these 22 activities that will help students feel inspired to study hard, perform well, and practice autonomous regulation.

1. The Share Chair

Nothing is more motivating than someone who cares! Kick off the year by decorating a chair to place right next to your desk. Explain to your students that they can sit down next to you at any time to discuss a topic they don’t understand, ask a homework question, or chat about their learning goals and challenges. Make It clear that you are available.

Learn More: The Owl Teacher

2. Change Of Scenery

Lesson planning that includes a different environment will help motivate your students to learn. Taking them to the site of a history lesson, for example, or even outside on the field are great ideas.

Learn More: Education Week

3. Stoke Their Competitive Fires

At the end of every week or month, host a quiz or interactive competition that pits students against one another. Keep it friendly to avoid negative associations and hand out homemade trophies to boost positive motivation.

Learn More: eHow

4. Think Up Their Own Reward

Make use of the self-determination theory and have your students plan out their own rewards to receive when they achieve a goal. For example, you could have the class decide on whether they will have a pizza party, a disco party, or a movie day if everyone hands in their project on time.

Learn More: Gretas Day

5. Create A Fun Corner

Decrease the school-related stress that your students experience by having a “calming corner” or “play area” in the classroom. Place teddy bears, board games, and other motivational activities behind a curtain or in a special cupboard, and allow students who have finished their work to play and enjoy a brain break.

Learn More: A Perfect Blend Teaching

6. Assign Some Responsibility

Feeling responsible for something will encourage students to want to come to school and learn. Have a class puppet or teddy bear that everyone has a turn taking care of over the weekend. Have your students include what they did with the classroom mascot in a joint diary. This motivation activity will support a positive correlation between school and having fun.

7. Leverage A Part of Their Daily Lives

Increase student motivation by allowing phones in the classroom for a short group project. Divide a sample of adolescents in your classroom into groups and have them create a TikTok video that explains a concept they’ve recently learned.

Learn More: Learning Liftoff

8. Give Them A Desk Pet

Give each student animal-shaped erasers or figurines to take care of whilst at school. Set up a points system where they can exchange points for food, clothing, or other accessories for their pet. This will assist with student motivation as they will be inspired to collect cute items for their pets by working hard to achieve points.

Learn More: We Are Teachers

9. Self-Reflection And Journaling

Reduce the negative effects that some children experience after being overstimulated at school by encouraging self-reflection with a journaling activity. This will keep your students calm and happy and will help your learners develop autonomous regulation and motivation.

Learn More: Journal Buddies

10. Make Your Enthusiasm Contagious

When you’re excited to learn, your students will be too! Improve the motivational aspects of your classroom by adding some fresh décor to it.

Learn More: Chaylor And Mads

11. Leverage Your Learner’s Unique Interests

Celebrate each of your students on a special theme day that is built around their favorite thing- like animals, a TV show, or baking. Decorate your class to match the theme and curate your lesson plan accordingly.

Learn More: Classroom Transformations

12. Finding It In Themselves

Intrinsic motivation will push your students further than you ever could. Encourage them to love learning on their own terms. Doing this will also have a stress-buffering effect as learners will have a greater goal to cling to when studying gets hard.

Learn More: Exam Study Expert

13. Build Physical Education Into Their Daily Lives

Many students feel anxious at school; particularly before tests or exams. Help these students by using physical activity as a way to reduce the impact of stress. Include games to get your learners moving in the classroom.

Learn More: Goodbye Anxiety Hello Joy

14. Celebrate Progress

Motivate your adolescent students using the extrinsic motivation tactic of inviting each student for a progress discussion in the class over yummy snacks. If you meet each student at their level once a term, they will see that you respect and care for them and their progress.

Learn More: Oh Happy Joy

15. Show You Care

Kick off the school year or a new term with a care package. Student motivation will skyrocket when they get their hands on snacks, activities, and useful items that will be of use during academic lessons!

Learn More: Rain And Pine

16. Classroom Yoga

The effects of stress can be minimized when you encourage students to get active in class. Teach self-regulation in the classroom by starting every day off with ten minutes of Yoga. Secondary outcomes of this exercise include students enjoying more mental clarity that will assist them in their academic lessons.

Learn More: Pink Oatmeal

17. Obstacle Course On The Field

Promote adolescent health and motivation when you encourage your students to take part in an obstacle course! Take a break from the classroom and get outside for some moderate-to-vigorous physical activity.

Learn More: Happy Toddler Playtime

18. Encourage Community

The primary outcome of any motivation activity should be to improve the positive association learners have with the school. Include socialization time in your lesson planning so that learners can bond with friends and enjoy spending time in your class.

Learn More: K12

19. Guest Speaker Day

Encourage self-determined motivation by inviting successful people from all walks of life to discuss how work ethic and behavioral regulation improved their quality of life.

Learn More: Edutopia

20. Create A Vision Board

Encouraging your students to be self-motivated will go a long way to ensuring their success well past the year that they spend as your student. Bring magazines, glitter glue, and glue to class and have each student collect, cut out and paste images that inspire them onto their boards. Having a greater life goal in mind will help them stay on track with their studies.

Learn More: Study All Knight

21. Break The Work Into Pieces

Make sure that your lesson planning involves breaking a complex subject or activity into manageable pieces. Students will build a positive correlation between working hard and enjoying school when they go at a pace that allows them to answer questions and digest the work.

Learn More: HCPSS

22. Encourage Evaluations

By making time for a self-evaluation exercise throughout the term, you will encourage behavioral regulation in your learners. Students will find it motivating to reflect on their learning journey and to set goals for the next term or year.

Learn More: Math Giraffe

How to Promote the Intrinsic Desire to Learn

Rather than relying on grades as external motivators, teachers can help students develop intrinsic motivation by providing opportunities for autonomy and building their sense of competence.

Your content has been saved!

A case can be made, and researchers have made it, that motivation is one of the keystones of teaching and learning (Dorn et al., 2017).

As an educator, based on my life and professional experience, I may have a fairly solid idea of what I believe students might need to know in order to be successful academically and professionally. However, how much does that matter if my students are not motivated to learn what I am teaching?

Of course, I can try to entice their interest through “dangling carrots” like grades, points, prizes, gold stars, etc, (or threatening “sticks” like detention or negative calls home). This kind of “extrinsic motivation” can work, but usually only for the short term and typically for tasks that don’t require much higher-order thinking (“Daniel Pink on Incentives and the Two Types of Motivation,” n.d.).

On the other hand, “intrinsic motivation” describes a situation where the energy to act comes more from inside the learner. In other words, the reward is the activity itself. The late educator Ken Robinson talked (Ferlazzo, 2012) about how farmers can’t force their crops to grow, but they can create the conditions that support their seeds' ability to grow—providing the right soil, water, and care. This description is similar to the challenge teachers face with encouraging student intrinsic motivation—we can’t make them have it, but we can create the classroom conditions where that kind of motivation is more likely to develop and flourish.

Extensive research documents the benefits of intrinsic motivation over the extrinsic kind. Intrinsic motivation tends to lead to greater academic achievement and a better sense of well-being (Burton et al., 2006) lasts longer, enhances creativity, and cultivates higher-order thinking (Brewster & Fager, 2000).

Extrinsic motivation tends to reduce long-term interest and effort in the topic at hand (Deci et al., 1999; Kohn, 2018; Wehe et al., 2015) and reduce creativity, as well (Hennessey, 2000). Research has found that motivation driven by extrinsic factors tends to lead to “decreased well-being” (Howard et al., 2021). Experiments using student rewards to improve academic achievement have failed repeatedly (Adams, 2014; Dietrichson et al., 2020; Ferlazzo, 2016). If and when incentives have resulted in very limited short-term “success,” researchers have found they tend to increase participants’ focus on the reward itself, not on the task. Work quality then suffers, and task interest tends to decline to previous levels—or below them—after the reward is given (Kohn, 2016).

Students, especially teens, in the United States report exceptionally high feelings of disengagement from school (Sparks, 2020; Yale University, 2020)—and that was before the COVID pandemic. It does not seem to be a stretch to consider that the high levels of extrinsic motivation present in most classes and schools might contribute to these strong negative perspectives.

Emphasizing intrinsic motivation also makes me feel better about myself as a teacher and, I believe, also contributes towards creating an overall class atmosphere of a “community of learners” instead of a “classroom of students.” No one wants to be treated like a rat in a maze, and I certainly don’t want to view myself as a teacher who even vaguely can be described as promoting that kind of system.

Does that mean I never use extrinsic motivation in my classroom? Of course not. I was a community organizer for nineteen years prior to becoming a secondary teacher twenty years ago. Organizers talk about working “in the world as it is” and not in “the world as we’d like it to be.” Creating the conditions to encourage student intrinsic motivation can sometimes be hard and time-consuming. It’s not at all unusual for me to offer extra credit, grade by using points, and offer healthy snacks as game prizes, and I am definitely not above sometimes “threatening” negative consequences for inappropriate behaviors. I am not a Pollyanna with my head up in the clouds, and live “in the world as it is.” However, often (though not always) when I apply “carrots,” I also briefly talk with students about how it is more of an exception to the “rule.” The “rule” is that I hope students generally do things in our class because they want to, and not because they feel a need to pursue rewards.

When it comes to using “sticks,” I try to follow the advice (with a slight adjustment) of Dr. Edward Deci, perhaps the preeminent researcher in the world on intrinsic motivation. He acknowledges that a negative consequence might have to be used, but then “you need to sit down the next afternoon when everyone’s calm, talk it through from both sides, then discuss ways so the behavior doesn’t happen again.... Always use the blow-up as a learning moment the next day” (Feiler, 2013, para. 18).

My modification to his advice comes from my community organizing experience, where we learned that “polarization” can happen, but that “depolarization” can be most effective if it happens fairly quickly. In that spirit, I try to make that follow-up conversation happen during the same class or track the student down later in the day.

It is also important to keep in mind that students—and the rest of us—can be motivated by both a desire to learn what is being taught and wanting a good grade, just as an interest in being a better teacher motivated me to write this book, as well as the possible additional income I could gain from royalties.

Let’s also recognize the role of what writer Daniel Pink calls “baseline rewards” (“Daniel Pink on Incentives and the Two Types of Motivation,” n.d.) and that is also supported by other research (Ferlazzo, 2015; Kaplan, 2015). The “baseline rewards” concept suggests that basic extrinsic “rewards” in a classroom (a caring teacher, engaging lessons, predictable and fair grading, cleanliness, respectful rules and atmosphere, etc.) or in a job situation (reasonable salary, safe working conditions) must be present for people to have any sort of motivation at all.

Absent those kinds of “baseline rewards” and participants will tend to focus on the inequitable and unfair situation rather than on learning or on being productive.

But even though I recognize the role of extrinsic motivation in the lives of my students and in my life, I am also constantly striving in my classroom to create “the world as I’d like it to be” by creating the conditions where intrinsic motivation can blossom. This book shares what teachers can do to make that world happen more often in our classes.

For effective educators, there is always tension between “the world as it is” and “the world as we’d like it to be.” If we always operate out of the former, we can become transactional pragmatists always settling for what appears to be the easiest short-term solution. If we always operate out of the latter, we can become hopeless sentimentalists who are likely to become disillusioned and burnt-out. But it’s not a question of either/or and, instead, it’s more of one considering which side do you tend to operate on, and if you tend to use the former to lead you to more of the latter. I would suggest that favoring that side of the coin is the perspective that is more likely to keep you—and your students—in a content and effective learning situation.

Researchers have identified four general areas that can contribute towards creating the conditions where intrinsic motivation can be supported (Center on Education Policy, 2012; Ryan & Deci, 2000), and they serve as the basis for the next four chapters in this book:

- Autonomy: having a degree of control over what needs to happen and how it can be done

- Competence: feeling that one has the ability to be successful in doing it

- Relatedness: doing the activity helps the student feel more connected to others, and feel cared about by people whom they respect

- Relevance: the work must be seen by students as interesting and valuable to them, and useful to their present lives and/or hopes and dreams for the future

Not everything we do in the classroom has to involve all four of these elements, but I do think we can include some of them in most of our lessons. There will be times, however, that students are required to do tasks that make it challenging to include even one of them (for example, taking state standardized tests). In those cases, I believe it’s a safe guess that students are likely to be more engaged in them if their teachers have emphasized the conditions for intrinsic motivation most of the rest of the time.

Excerpt from The Student Motivation Handbook: 50 Ways to Boost an Intrinsic Desire to Learn by Larry Ferlazzo, © 2023 Routledge/Taylor & Francis, Used with permission.

Home > Blog > Tips for Online Students > Must Know Tips for Student Motivation

School Life Balance , Tips for Online Students

Must Know Tips for Student Motivation

Updated: June 19, 2024

Published: March 3, 2019

Lack of motivation in students is one of the biggest problems in the world. It is not only a problem but it is also affecting the education system. If you’ve ever felt like your schoolwork has been a struggle, you’re not alone. Studies show that students across the country are feeling less motivated to learn and more stressed about how their grades will affect their future career options.

New students are filled with will and zeal, slowly fading away, calling for some little prodding to have work done avoidable through student motivation. But it doesn’t have to be that way. This blog will cover useful student motivation tips-and it’s never too late to start putting them to use.

What is student motivation?

Motivation is simply a person’s willingness to exert physical or mental effort to complete a predetermined goal. In his quote, Samuel L. Johnson, a writer who made a huge contribution to a dictionary of the English language, about curiosity is in great and generous minds, the first passion and the last, enlighten us that motivation for students is the engine and fuel for prolonged love of learning. It’s therefore paramount to run programs parallel to academics that provide student motivation tips. Three parameters define motivation choice, effort and persistence, categorizing motivation under two levels intrinsic and extrinsic motivations.

What is the difference between intrinsic and extrinsic student motivation?

Intrinsic student motivation.

Intrinsic motivation is associated with internal rewards where students learn to value learning due to its merits regardless of external factors. The students’ drive motivates them unconditionally.

Extrinsic student motivation

Extrinsic motivation is characterized by external factors example, the student may be motivated to learn to pass the exams or avoid punishment. Students lose attachment if they are motivated externally.

Intrinsic motivation tips for students

Student’s interest .

Assignments and projects should align with the student’s areas of interest to encourage high student participation. With interest in heart, the student will always endeavor to discover more in that field, boosting their motivation.

Reward

Choose rewards that encourage the student’s intrinsic interests. This is after identifying the student’s interests to continue with the pursuit of their interest. Setting rewards and gifts in their interests will motivate the student to do even more. Reward the student’s best performance to encourage them to soar higher.

Student’s encouragement over assignments

Blended learning is a strategy that involves a series of independent learning and whole-class lessons. The students are encouraged to share what they learned in class lessons to build their experiences and lessons with certain topics.

Positive feedback on student assignments

Appreciation works magic with student motivation. The positive feedback that aims to encourage students to do better is a great motivation tip for the students. This is necessary, especially if the student did not generally perform well in the assignment. Therefore, they should be encouraged on what to improve to make their assignments better.

“Curiosity is the mother of all invention.” The student’s curiosity should be harnessed and used to inspire them to further their learning positively. Finding out what the students are curious about and investing in helping them find answers and discover more helps to motivate them in areas of their interests.

Shared enthusiasm

Trainers and students should have a common ground of synchronized interest. This means that the trainer and the student share similar views towards a topic or a learning field. Hence creating a sense of value for the students. In addition, the student can utilize the online discussion boards for online coursework to interact with the trainer and fellow students.

Conducive learning environment

A learning environment free of bias, ill-treatment, prejudices, racism and favoritism will give the students a sense of belonging. Be a champion of equality for all by instilling positive relationships within the learning environment. This will consequently encourage the students to build their confidence as a motivation for them. Study shows online learning helps to motivate students.

Teamwork building

Sometimes motivation comes from the people around us. They can be our friends, family and peers. Student teamwork building is critical in creating confidence within the students. A student study group with shared activities helps build motivation by sharing common ideas.

Real-life inspiration stories

Inspirational real-life student stories are always fascinating. They give the students hope, especially with their prevailing conditions and nature. Successful real-life stories motivate students to have courage and determination in their pursuit of learning. Relatable life experiences strike a desire for success within the students by assuring them that their dreams are attainable.

Fun sessions and activities

Students should be exposed to more than classroom activities to be productive. A trainer s should entail fun elements in the class schedule to lift their spirits and encourage participation. Online games and other social activities should be part of fun sessions. The students can also participate by suggesting their activities.

As much as intrinsic motivation is concerned, the students should also have their motivations. Therefore, the following are motivation tips students should practice.

Be perspective

Sometimes a student may feel a drag on their learning. It’s normal for anyone, but students should always have a purpose for what they want. All the tasks in learning have a common good in the end, and that should be a motivation for the student.

Be competitive

Students should strive to be better by setting goals for themselves. This includes working towards a certain personal best and going beyond. Exploring their best areas and maximizing them is an excellent motivation for the student.

Get your eyes on the prize

A student should always set goals and create timelines for completing the tasks.

Get support

Finally, the student should request support from family, friends and peers on tasks they cannot do independently. They should also indulge their trainers and create a good relationship with them for student motivation.

The student can also join a motivational class for support. Organizations host these classes’ camps and seminars to help students who lack motivation. It’s also advisable to follow your influential motivational speaker sessions or videos regularly.

Find a Program that Matches Your Ambition

Motivation also depends on the program you are studying as astudent and how you arrived to it. A wide range of programs give you the flexibility to pursue a program that matches your ambition. At the University of The People , we are a reputable online university offering a wide range of American accredited programs for any qualified applicant. We nurture students’ academic abilities by establishing an outstanding student body. We offer 100%- online certificate,associate degree, bachelor’s and masters degree programs . Visit our blog for more insights.

At UoPeople, our blog writers are thinkers, researchers, and experts dedicated to curating articles relevant to our mission: making higher education accessible to everyone. Read More

In this article

Here is our offer line or any promotional text goes here Hurry up!

Home / Blog

8 Ways To Stay Motivated To Complete Assignments

When you enter college, you get blasted with many responsibilities. Some are new to you, while others are not. The new things can take you a lot of time to learn. One new thing you have to learn and master is assignment writing . Yes, assignments are a big part of college life.

If you haven’t started college yet, you may be thinking that we’re exaggerating things. But, that’s not the case. Learning how to write assignments in college is crucial. Students who don’t learn it take expert help from websites like Grow With Grades (GWG), which isn’t bad, in our opinion.

Taking help occasionally isn’t bad. What’s bad is when you don’t learn how to write assignments throughout your time spent at college. We're writing this blog to stop you from dealing with this problem. This blog will tell you 8 ways to stay motivated to complete assignments.

Let’s start.

Put An End To Procrastination

The first thing you want to take care of while writing assignments is to end procrastination. It is the number one enemy of a good and productive life. We know you love to sleep whenever you get time. But taking multiple naps throughout the day isn’t a good thing.

Procrastination can also look like using your smartphone, even after knowing that you have assignments to complete. Whatever is causing you to procrastinate, you need to find a solution ASAP.

The thing with procrastination is that it can stop you from completing the simplest of tasks. Consider you get 10 days for completing assignments . You can still not do it if you have a habit of procrastinating. You may not realize it now, but it is a big problem that will stop you from succeeding in life.

Put Distractions Aside

Often some things lead you to procrastinate. And the most common is a smartphone. Parents reading this blog will agree that smartphones are indeed why they argue with their children. Children these days use smartphones for hours on end because they can do everything using them. From taking notes in class to setting reminders for assignment submission, there is no end to what can be done using smartphones.

When children have access to smartphones from a young age, they’re very likely to develop a habit. And developing a habit of using smartphones is never good because it can stop you from focusing on what’s important and start indulging in timepass activities.

So, from now on, when you’re about to start assignment writing , make sure to keep your smartphone away from you, preferably in the other room. Initially, you may want to use your smartphone every few minutes. But once you develop a habit, not using it will become a habit for you.

Do Extensive Research

You can’t straight away decide to write assignments when the professor asks you to. When you do it, assignment writing becomes boring, which is why you can’t stay motivated. There’s a very simple way you can counter this problem.

The way is by doing extensive research. When you research, you learn many things, and the task does not stay boring at all. Moreover, research is crucial for any assignment because you can’t complete it if you don’t research.

Make sure to search for information from multiple resources. When you do it, you identify any wrong information you might include if you don’t check multiple resources. We recommend you check research papers because they have the most credible information.

Create An Outline

You feel bored and lack motivation when you don’t begin the work. Often starting something is the hardest thing. You’ll realize it when you have to write assignments. Starting them is like a challenge, but you realize writing the other parts becomes fairly easy when you start writing.

So, what you can do is create an outline for the assignment. Outline means to create the introduction and different headings. When you do it, you put an end to boredom and have a rough idea about what you’ll write. And when you have done some work, you stay motivated to complete the rest.

Reward Yourself

Writing assignments continuously can be tiring. We assure you that no one (even the best writers) can do it.

So, what’s the solution when you’re tight on deadlines?

A very good solution is to start rewarding yourself. The reward can be anything from tasty food to watching funny videos. There is no limitation to what a reward can look like. Whatever makes you appreciate your efforts can be a reward.

You might have seen many people these days intentionally make their lives harder. They do it in the name of evolving through challenges. While it is true that a person grows when they go through challenges, it isn’t a good practice to create them forcefully. We all have to realize how crucial it is to appreciate ourselves.

And occasionally eating your favourite food won’t make you fat. So, stop thinking about it and reward yourself often.

Take A Walk

The breaks you take when writing assignments aren’t a waste of time. They are meant to refresh your mind and body, which are essential if you want to keep your productivity high. You can either sit idle or take a walk.

Taking a walk is a pretty good habit , as it can refresh your mind. When you walk in nature, your eyes, mind and entire body feels refreshed. If you’re looking to lose fat, walking is a good choice. You don’t necessarily have to run or go to a gym to get in good shape. Brisk walking can burn a lot of calories, and it is the perfect choice for people with busy schedules.

Ask Your Friends What You Don’t Understand

It is common for students in college not to know everything about all the subjects. It could be because they are interested in a specific subject or just don’t have enough time to become good at everything. When this happens, students can ask their friends to teach them what they don’t know.

We feel asking your college friends about topics you don’t understand is a very good thing. You can’t always approach your professor and ask them about your doubts. Well, you can, but most students are not comfortable doing it. If you are or want to learn how to be your professor’s favourite student, we recommend you read this blog .

Anyways, when you take help from your friends, you don’t have to speak in a formal tone, as you would with your professors. Another benefit is that your relation with your friends will strengthen. You never know which friends can become your best friends, and you may end up staying in touch with them for many years.

Know The Negative Consequences

For some students, positive things don’t work. They have to think about the negative consequences to get motivation. In college, it means they have to think that they can fail if they don’t complete and submit their assignments on time.

Many people crumble under pressure, but some love working under it. Many athletes deal with pressure when the race is about to start. But whenever any news reporter asks them how they’re feeling, they always reply that they’re excited. That’s because the same part of your brain works when you’re under pressure and excited.

So, if thinking about negative consequences motivates you to take action and complete assignments, resort to it.

Staying motivated while writing assignments is difficult because there are some challenges that one is presented with. If you also lose motivation easily while doing assignments, you need to read this blog. That’s because, in this blog, we covered 8 ways to stay motivated to complete assignments. After reading this blog, we hope that you won’t have trouble finding motivation.

If you liked reading it, share it with your college friends.

RECENT BLOG

A Guide to Figurative Language...

Tap into Your Academic Potenti...

How to Overcome Procrastinatio...

Elevate Your Grades: Partnerin...

Recent posts, a guide to figurative language, tap into your academic potential: avail elite assignment help, how to overcome procrastination and get your assignments done on time, elevate your grades: partnering with grow with grades for academic success, college tips, career tips, assignment tips, grab the best assignment now, 24*7 support.

Daniel Wong

30 Tips to Stop Procrastinating and Find Motivation to Do Homework

Updated on June 6, 2023 By Daniel Wong 45 Comments

To stop procrastinating on homework, you need to find motivation to do the homework in the first place.

But first, you have to overcome feeling too overwhelmed to even start.

You know what it feels like when everything hits you at once, right?

You have three tests to study for and a math assignment due tomorrow.

And you’ve got a history report due the day after.

You tell yourself to get down to work. But with so much to do, you feel overwhelmed.

So you procrastinate.

You check your social media feed, watch a few videos, and get yourself a drink. But you know that none of this is bringing you closer to getting the work done.

Does this sound familiar?

Don’t worry – you are not alone. Procrastination is a problem that everyone faces, but there are ways around it.

By following the tips in this article, you’ll be able to overcome procrastination and consistently find the motivation to do the homework .

So read on to discover 30 powerful tips to help you stop procrastinating on your homework.

Enter your email below to download a PDF summary of this article. The PDF contains all the tips found here, plus 3 exclusive bonus tips that you’ll only find in the PDF.

How to stop procrastinating and motivate yourself to do your homework.

Procrastination when it comes to homework isn’t just an issue of laziness or a lack of motivation .

The following tips will help you to first address the root cause of your procrastination and then implement strategies to keep your motivation levels high.

1. Take a quiz to see how much you procrastinate.

The first step to changing your behavior is to become more self-aware.

How often do you procrastinate? What kinds of tasks do you tend to put off? Is procrastination a small or big problem for you?

To answer these questions, I suggest that you take this online quiz designed by Psychology Today .

2. Figure out why you’re procrastinating.

Procrastination is a complex issue that involves multiple factors.

Stop thinking of excuses for not doing your homework , and figure out what’s keeping you from getting started.

Are you procrastinating because:

- You’re not sure you’ll be able to solve all the homework problems?

- You’re subconsciously rebelling against your teachers or parents?

- You’re not interested in the subject or topic?

- You’re physically or mentally tired?

- You’re waiting for the perfect time to start?

- You don’t know where to start?

Once you’ve identified exactly why you’re procrastinating, you can pick out the tips in this article that will get to the root of the problem.

3. Write down what you’re procrastinating on.

Students tend to procrastinate when they’re feeling stressed and overwhelmed.

But you might be surprised to discover that simply by writing down the specific tasks you’re putting off, the situation will feel more manageable.

It’s a quick solution, and it makes a real difference.

Give it a try and you’ll be less likely to procrastinate.

4. Put your homework on your desk.

Here’s an even simpler idea.

Many times, the hardest part of getting your homework done is getting started.

It doesn’t require a lot of willpower to take out your homework and put it on your desk.

But once it’s sitting there in front of you, you’ll be much closer to actually getting down to work.

5. Break down the task into smaller steps.

This one trick will make any task seem more manageable.

For example, if you have a history report to write, you could break it down into the following steps:

- Read the history textbook

- Do online research

- Organize the information

- Create an outline

- Write the introduction

- Write the body paragraphs

- Write the conclusion

- Edit and proofread the report

Focus on just one step at a time. This way, you won’t need to motivate yourself to write the whole report at one go.

This is an important technique to use if you want to study smart and get more done .

6. Create a detailed timeline with specific deadlines.

As a follow-up to Point #5, you can further combat procrastination by creating a timeline with specific deadlines.

Using the same example above, I’ve added deadlines to each of the steps:

- Jan 30 th : Read the history textbook

- Feb 2 nd : Do online research

- Feb 3 rd : Organize the information

- Feb 5 th : Create an outline

- Feb 8 th : Write the introduction

- Feb 12 th : Write the body paragraphs

- Feb 14 th : Write the conclusion

- Feb 16 th : Edit and proofread the report

Assigning specific dates creates a sense of urgency, which makes it more likely that you’ll keep to the deadlines.

7. Spend time with people who are focused and hardworking.

Jim Rohn famously said that you’re the average of the five people you spend the most time with.

If you hang out with people who are motivated and hardworking, you’ll become more like them.

Likewise, if you hang out with people who continually procrastinate, you’ll become more like them too.

Motivation to do homework naturally increases when you surround yourself with the right people.

So choose your friends wisely. Find homework buddies who will influence you positively to become a straight-A student who leads a balanced life.

That doesn’t mean you can’t have any fun! It just means that you and your friends know when it’s time to get down to work and when it’s time to enjoy yourselves.

8. Tell at least two or three people about the tasks you plan to complete.

When you tell others about the tasks you intend to finish, you’ll be more likely to follow through with your plans.

This is called “accountability,” and it kicks in because you want to be seen as someone who keeps your word.

So if you know about this principle, why not use it to your advantage?

You could even ask a friend to be your accountability buddy. At the beginning of each day, you could text each other what you plan to work on that day.

Then at the end of the day, you could check in with each other to see if things went according to plan.

9. Change your environment .

Maybe it’s your environment that’s making you feel sluggish.

When you’re doing your homework, is your super-comfortable bed just two steps away? Or is your distracting computer within easy reach?

If your environment is part of your procrastination problem, then change it.

Sometimes all you need is a simple change of scenery. Bring your work to the dining room table and get it done there. Or head to a nearby café to complete your report.

10. Talk to people who have overcome their procrastination problem.

If you have friends who consistently win the battle with procrastination, learn from their experience.

What was the turning point for them? What tips and strategies do they use? What keeps them motivated?

Find all this out, and then apply the information to your own situation.

11. Decide on a reward to give yourself after you complete your task.

“Planned” rewards are a great way to motivate yourself to do your homework.

The reward doesn’t have to be something huge.

For instance, you might decide that after you finish 10 questions of your math homework, you get to watch your favorite TV show.

Or you might decide that after reading one chapter of your history textbook, you get to spend 10 minutes on Facebook.

By giving yourself a reward, you’ll feel more motivated to get through the task at hand.

12. Decide on a consequence you’ll impose on yourself if you don’t meet the deadline.

It’s important that you decide on what the consequence will be before you start working toward your goal.

As an example, you could tell your younger brother that you’ll give him $1 for every deadline you don’t meet (see Point #6).

Or you could decide that you’ll delete one game from your phone for every late homework submission.

Those consequences would probably be painful enough to help you get down to work, right?

13. Visualize success.

Take 30 seconds and imagine how you’ll feel when you finish your work.

What positive emotions will you experience?

Will you feel a sense of satisfaction from getting all your work done?

Will you relish the extra time on your hands when you get your homework done fast and ahead of time?

This simple exercise of visualizing success may be enough to inspire you to start doing your assignment.

14. Visualize the process it will take to achieve that success.

Even more important than visualizing the outcome is visualizing the process it will take to achieve that outcome.

Research shows that focusing on the process is critical to success. If you’re procrastinating on a task, take a few moments to think about what you’ll need to do to complete it.

Visualize the following:

- What resources you’ll need

- Who you can turn to for help

- How long the task will take

- Where you’ll work on the task

- The joy you’ll experience as you make progress

This kind of visualization is like practice for your mind.

Once you understand what’s necessary to achieve your goal, you’ll find that it’s much easier to get down to work with real focus. This is key to doing well in school .

15. Write down why you want to complete the task.

You’ll be more motivated when you’re clear about why you want to accomplish something.

To motivate yourself to do your homework, think about all the ways in which it’s a meaningful task.

So take a couple of minutes to write down the reasons. Here are some possible ones:

- Learn useful information

- Master the topic

- Enjoy a sense of accomplishment when you’ve completed the task

- Become a more focused student

- Learn to embrace challenges

- Fulfill your responsibility as a student

- Get a good grade on the assignment

16. Write down the negative feelings you’ll have if you don’t complete the task.

If you don’t complete the assignment, you might feel disappointed or discouraged. You might even feel as if you’ve let your parents or your teacher – or even yourself – down.

It isn’t wise to dwell on these negative emotions for too long. But by imagining how you’ll feel if you don’t finish the task, you’ll realize how important it is that you get to work.

17. Do the hardest task first.

Most students will choose to do the easiest task first, rather than the hardest one. But this approach isn’t effective because it leaves the worst for last.

It’s more difficult to find motivation to do homework in less enjoyable subjects.

As Brian Tracy says , “Eat that frog!” By this, he means that you should always get your most difficult task out of the way at the beginning of the day.

If math is your least favorite subject, force yourself to complete your math homework first.

After doing so, you’ll feel a surge of motivation from knowing it’s finished. And you won’t procrastinate on your other homework because it will seem easier in comparison.

(On a separate note, check out these tips on how to get better at math if you’re struggling.)

18. Set a timer when doing your homework.

I recommend that you use a stopwatch for every homework session. (If you prefer, you could also use this online stopwatch or the Tomato Timer .)

Start the timer at the beginning of the session, and work in 30- to 45-minute blocks.

Using a timer creates a sense of urgency, which will help you fight off your urge to procrastinate.

When you know you only have to work for a short session, it will be easier to find motivation to complete your homework.

Tell yourself that you need to work hard until the timer goes off, and then you can take a break. (And then be sure to take that break!)

19. Eliminate distractions.

Here are some suggestions on how you can do this:

- Delete all the games and social media apps on your phone

- Turn off all notifications on your phone

- Mute your group chats

- Archive your inactive chats

- Turn off your phone, or put it on airplane mode

- Put your phone at least 10 feet away from you

- Turn off the Internet access on your computer

- Use an app like Freedom to restrict your Internet usage

- Put any other distractions (like food, magazines and books unrelated to your homework) at the other end of the room

- Unplug the TV

- Use earplugs if your surroundings are noisy

20. At the start of each day, write down the two to three Most Important Tasks (MITs) you want to accomplish.

This will enable you to prioritize your tasks. As Josh Kaufman explains , a Most Important Task (MIT) is a critical task that will help you to get significant results down the road.

Not all tasks are equally important. That’s why it’s vital that you identify your MITs, so that you can complete those as early in the day as possible.

What do you most need to get done today? That’s an MIT.

Get to work on it, then feel the satisfaction that comes from knowing it’s out of the way.

21. Focus on progress instead of perfection.

Perfectionism can destroy your motivation to do homework and keep you from starting important assignments.

Some students procrastinate because they’re waiting for the perfect time to start.

Others do so because they want to get their homework done perfectly. But they know this isn’t really possible – so they put off even getting started.

What’s the solution?

To focus on progress instead of perfection.

There’s never a perfect time for anything. Nor will you ever be able to complete your homework perfectly. But you can do your best, and that’s enough.

So concentrate on learning and improving, and turn this into a habit that you implement whenever you study .

22. Get organized.

Procrastination is common among students who are disorganized.

When you can’t remember which assignment is due when or which tests you have coming up, you’ll naturally feel confused. You’ll experience school- and test-related stress .

This, in turn, will lead to procrastination.

That’s why it’s crucial that you get organized. Here are some tips for doing this:

- Don’t rely on your memory ; write everything down

- Keep a to-do list

- Use a student planner

- Use a calendar and take note of important dates like exams, project due dates, school holidays , birthdays, and family events

- At the end of each day, plan for the following day

- Use one binder or folder for each subject or course

- Do weekly filing of your loose papers, notes, and old homework

- Throw away all the papers and notes you no longer need

23. Stop saying “I have to” and start saying “I choose to.”

When you say things like “I have to write my essay” or “I have to finish my science assignment,” you’ll probably feel annoyed. You might be tempted to complain about your teachers or your school .

What’s the alternative?

To use the phrase “I choose to.”

The truth is, you don’t “have” to do anything.

You can choose not to write your essay; you’ll just run the risk of failing the class.

You can choose not to do your science assignment; you’ll just need to deal with your angry teacher.

When you say “I choose to do my homework,” you’ll feel empowered. This means you’ll be more motivated to study and to do what you ought to.

24. Clear your desk once a week.

Clutter can be demotivating. It also causes stress , which is often at the root of procrastination.

Hard to believe? Give it a try and see for yourself.

By clearing your desk, you’ll reduce stress and make your workspace more organized.

So set a recurring appointment to organize your workspace once a week for just 10 minutes. You’ll receive huge benefits in the long run!

25. If a task takes two minutes or less to complete, do it now.

This is a principle from David Allen’s bestselling book, Getting Things Done .

You may notice that you tend to procrastinate when many tasks pile up. The way to prevent this from happening is to take care of the small but important tasks as soon as you have time.

Here are some examples of small two-minute tasks that you should do once you have a chance:

- Replying to your project group member’s email

- Picking up anything on the floor that doesn’t belong there

- Asking your parents to sign a consent form

- Filing a graded assignment

- Making a quick phone call

- Writing a checklist

- Sending a text to schedule a meeting

- Making an online purchase that doesn’t require further research

26. Finish one task before starting on the next.

You aren’t being productive when you switch between working on your literature essay, social studies report, and physics problem set – while also intermittently checking your phone.

Research shows that multitasking is less effective than doing one thing at a time. Multitasking may even damage your brain !

When it comes to overcoming procrastination, it’s better to stick with one task all the way through before starting on the next one.

You’ll get a sense of accomplishment when you finish the first assignment, which will give you a boost of inspiration as you move on to the next one.

27. Build your focus gradually.

You can’t win the battle against procrastination overnight; it takes time. This means that you need to build your focus progressively.

If you can only focus for 10 minutes at once, that’s fine. Start with three sessions of 10 minutes a day. After a week, increase it to three sessions of 15 minutes a day, and so on.

As the weeks go by, you’ll become far more focused than when you first started. And you’ll soon see how great that makes you feel.

28. Before you start work, write down three things you’re thankful for.

Gratitude improves your psychological health and increases your mental strength .

These factors are linked to motivation. The more you practice gratitude, the easier it will be to find motivation to do your homework. As such, it’s less likely that you’ll be a serial procrastinator.

Before you get down to work for the day, write down three things you’re thankful for. These could be simple things like good health, fine weather, or a loving family.

You could even do this in a “gratitude journal,” which you can then look back on whenever you need a shot of fresh appreciation for the good things in your life.

Either way, this short exercise will get you in the right mindset to be productive.

29. Get enough sleep.

For most people, this means getting 7 to 9 hours of sleep every night. And teenagers need 8 to 10 hours of sleep a night to function optimally.

What does sleep have to do with procrastination?

More than you might realize.

It’s almost impossible to feel motivated when you’re tired. And when you’re low on energy, your willpower is depleted too.

That’s why you give in to the temptation of Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube videos more easily when you’re sleep-deprived.

Here are ways to get more sleep , and sleep better too:

- Create a bedtime routine

- Go to sleep at around the same time every night

- Set a daily alarm as a reminder to go to bed

- Exercise regularly (but not within a few hours of bedtime)

- Make your bedroom as dark as possible

- Remove or switch off all electronic devices before bedtime

- Avoid caffeine at least six hours before bedtime

- Use an eye mask and earplugs

30. Schedule appointments with yourself to complete your homework.

These appointments are specific blocks of time reserved for working on a report, assignment, or project. Scheduling appointments is effective because it makes the task more “official,” so you’re more likely to keep the appointment.

For example, you could schedule appointments such as:

- Jan 25 th , 4:00 pm – 5:30 pm: Math assignment

- Jan 27 th , 3:00 pm – 4:00 pm: Online research for social studies project

- Jan 28 th , 4:30 pm – 5:00 pm: Write introduction for English essay

Transform homework procrastination into homework motivation

Procrastination is a problem we all face.

But given that you’ve read all the way to here, I know you’re committed to overcoming this problem.

And now that you’re armed with these tips, you have all the tools you need to become more disciplined and focused .

By the way, please don’t feel as if you need to implement all the tips at once, because that would be too overwhelming.

Instead, I recommend that you focus on just a couple of tips a week, and make gradual progress. No rush!

Over time, you’ll realize that your habit of procrastination has been replaced by the habit of getting things done.

Now’s the time to get started on that process of transformation. 🙂

Like this article? Please share it with your friends.

Images: Student and books , Homework , Group of students , Consequences , Why , Writing a list , Organized desk , Gratitude

January 19, 2016 at 11:53 am

Ur tips are rlly helpful. Thnkyou ! 🙂

January 19, 2016 at 1:43 pm

You’re welcome 🙂

August 29, 2018 at 11:21 am

Thanks very much

February 19, 2019 at 1:38 pm

The funny thing is while I was reading the first few steps of this article I was procrastinating on my homework….

November 12, 2019 at 12:44 pm

same here! but now I actually want to get my stuff done… huh

December 4, 2022 at 11:35 pm

May 30, 2023 at 6:26 am

October 25, 2023 at 11:35 am

fr tho i totally was but now I’m actually going to get started haha

June 6, 2020 at 6:04 am

I love your articles

January 21, 2016 at 7:07 pm

Thanks soo much. It’s almost like you could read my mind- when I felt so overwhelmed with the workload heap I had created for myself by procrastination, I know feel very motivated to tackle it out completely and replace that bad habit with the wonderful tips mentioned here! 🙂

January 21, 2016 at 8:04 pm

I’m glad to help 🙂

January 25, 2016 at 3:09 pm

You have shared great tips here. I especially like the point “Write down why you want to complete the task” because it is helpful to make us more motivated when we are clear about our goals

January 25, 2016 at 4:51 pm

Glad that you found the tips useful, John!

January 29, 2016 at 1:22 am

Thank you very much for your wonderful tips!!! ☺☺☺

January 29, 2016 at 10:41 am

It’s my joy to help, Kabir 🙂

February 3, 2016 at 12:57 pm

Always love your articles. Keep them up 🙂

February 3, 2016 at 1:21 pm

Thanks, Matthew 🙂

February 4, 2016 at 1:40 pm

There are quite a lot of things that you need to do in order to come out with flying colors while studying in a university away from your homeland. Procrastinating on homework is one of the major mistakes committed by students and these tips will help you to avoid them all and make yourself more efficient during your student life.

February 4, 2016 at 1:58 pm

Completely agreed, Leong Siew.

October 5, 2018 at 12:52 am

Wow! thank you very much, I love it .

November 2, 2018 at 10:45 am

You are helping me a lot.. thank you very much….😊

November 6, 2018 at 5:19 pm

I’m procrastinating by reading this

November 29, 2018 at 10:21 am

January 8, 2021 at 3:38 am

March 3, 2019 at 9:12 am

Daniel, your amazing information and advice, has been very useful! Please keep up your excellent work!

April 12, 2019 at 11:12 am

We should stop procrastinating.

September 28, 2019 at 5:19 pm

Thank you so much for the tips:) i’ve been procrastinating since i started high schools and my grades were really bad “F” but the tips have made me a straight A student again.

January 23, 2020 at 7:43 pm

Thanks for the tips, Daniel! They’re really useful! 😁

April 10, 2020 at 2:15 pm

I have always stood first in my class. But procrastination has always been a very bad habit of mine which is why I lost marks for late submission .As an excuse for finding motivation for studying I would spend hours on the phone and I would eventually procrastinate. So I tried your tips and tricks today and they really worked.i am so glad and thankful for your help. 🇮🇳Love from India🇮🇳

April 15, 2020 at 11:16 am

Well I’m gonna give this a shot it looks and sounds very helpful thank you guys I really needed this

April 16, 2020 at 9:48 pm

Daniel, your amazing information and advice, has been very useful! keep up your excellent work! May you give more useful content to us.

May 6, 2020 at 5:03 pm

nice article thanks for your sharing.

May 20, 2020 at 4:49 am

Thank you so much this helped me so much but I was wondering about like what if you just like being lazy and stuff and don’t feel like doing anything and you don’t want to tell anyone because you might annoy them and you just don’t want to add your problems and put another burden on theirs

July 12, 2020 at 1:55 am

I’ve read many short procrastination tip articles and always thought they were stupid or overlooking the actual problem. ‘do this and this’ or that and that, and I sit there thinking I CAN’T. This article had some nice original tips that I actually followed and really did make me feel a bit better. Cheers, diving into what will probably be a 3 hour case study.

August 22, 2020 at 10:14 pm

Nicely explain each tips and those are practical thanks for sharing. Dr.Achyut More

November 11, 2020 at 12:34 pm

Thanks a lot! It was very helpful!

November 15, 2020 at 9:11 am

I keep catching myself procrastinating today. I started reading this yesterday, but then I realized I was procrastinating, so I stopped to finish it today. Thank you for all the great tips.

November 30, 2020 at 5:15 pm

Woow this is so great. Thanks so much Daniel

December 3, 2020 at 3:13 am

These tips were very helpful!

December 18, 2020 at 11:54 am

Procrastination is a major problem of mine, and this, this is very helpful. It is very motivational, now I think I can complete my work.

December 28, 2020 at 2:44 pm

Daniel Wong: When you’re doing your homework, is your super-comfortable bed just two steps away? Me: Nope, my super-comfortable bed is one step away. (But I seriously can’t study anywhere else. If I go to the dining table, my mum would be right in front of me talking loudly on the phone with colleagues and other rooms is an absolute no. My mum doesn’t allow me to go outside. Please give me some suggestions. )

September 19, 2022 at 12:14 pm

I would try and find some noise cancelling headphones to play some classical music or get some earbuds to ignore you mum lol

March 1, 2021 at 5:46 pm

Thank you very much. I highly appreciate it.

May 12, 2023 at 3:38 am

This is great advice. My little niece is now six years old and I like to use those nice cheap child friendly workbooks with her. This is done in order to help her to learn things completely on her own. I however prefer to test her on her own knowledge however. After a rather quick demonstration in the lesson I then tend to give her two simple questions to start off with. And it works a treat. Seriously. I love it. She loves it. The exam questions are for her to answer on her own on a notepad. If she can, she will receive a gold medal and a box of sweets. If not she only gets a plastic toy. We do this all the time to help her understand. Once a week we spend up to thirty minutes in a math lesson on this technique for recalling the basic facts. I have had a lot of great success with this new age technique. So I’m going to carry on with it for now.

October 31, 2024 at 10:58 pm

Is it possible that our education system is failing to engage students in a way that inspires them to do their homework, leading to a lack of motivation?”, “refusal

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

EdTrust in Texas advocates for an equitable education for Black and Latino students and students from low-income backgrounds across the state. We believe in centering the voices of Texas students and families as we work alongside them for the better future they deserve.

Our mission is to close the gaps in opportunity and achievement that disproportionately impact students who are the most underserved, with a particular focus on Black and Latino/a students and students from low-income backgrounds.

EdTrust–New York is a statewide education policy and advocacy organization focused first and foremost on doing right by New York’s children. Although many organizations speak up for the adults employed by schools and colleges, we advocate for students, especially those whose needs and potential are often overlooked.

EdTrust-Tennessee advocates for equitable education for historically-underserved students across the state. We believe in centering the voices of Tennessee students and families as we work alongside them for the future they deserve.

EdTrust–West is committed to dismantling the racial and economic barriers embedded in the California education system. Through our research and advocacy, EdTrust-West engages diverse communities dedicated to education equity and justice and increases political and public will to build an education system where students of color and multilingual learners, especially those experiencing poverty, will thrive.

The Education Trust in Louisiana works to promote educational equity for historically underserved students in the Louisiana’s schools. We work alongside students, families, and communities to build urgency and collective will for educational equity and justice.

EdTrust in Texas advocates for an equitable education for historically-underserved students across the state. We believe in centering the voices of Texas students and families as we work alongside them for the better future they deserve.

EdTrust in Washington advocates for an equitable education for historically-underserved students across the state. We believe in centering the voices of Washington students and families as we work alongside them for the better future they deserve.

Massachusetts

The Education Trust team in Massachusetts convenes and supports the Massachusetts Education Equity Partnership (MEEP), a collective effort of more than 20 social justice, civil rights and education organizations from across the Commonwealth working together to promote educational equity for historically underserved students in our state’s schools.

Home – Research, Tools & Insights – Report

Motivation and Engagement in Student Assignments

When students have the opportunity to attend classes that are engaging, creative, and relatable to their lives, they are…

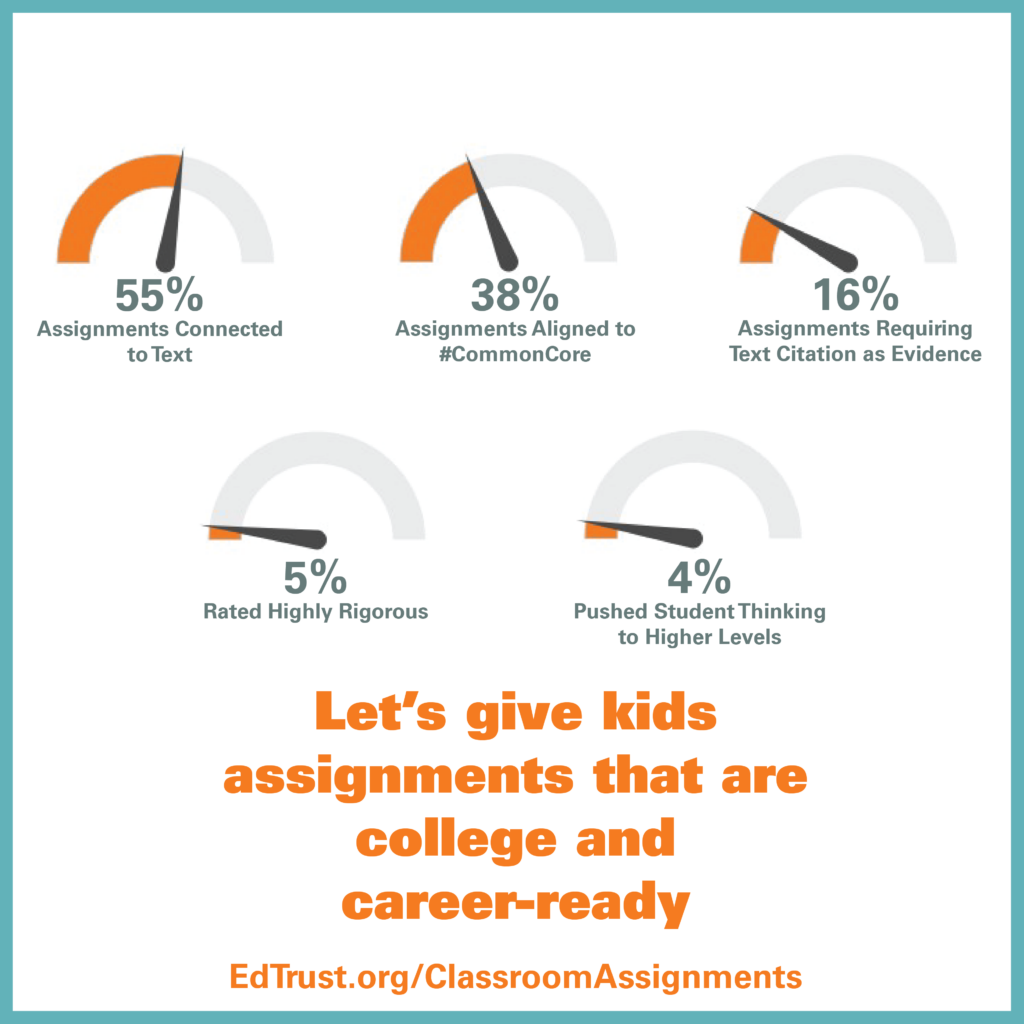

When students have the opportunity to attend classes that are engaging, creative, and relatable to their lives, they are more likely to succeed academically. Unfortunately, several new analyses have found that far too many students experience classroom assignments that fail to prepare them for life beyond school.

In a new report , we examined two powerful levers for engaging learners — choice and relevancy — and explored how educators can use these levers to increase student motivation and engagement.

“Classroom assignments — the daily tasks we ask our students to do — are a powerful lens for viewing teaching and learning. They reflect how students experience a curriculum and reveal a teacher’s expectations of what students can achieve.”

— Tanji Reed Marshall, Ph.D., senior associate of P-12 practice

Under our current college- and career-ready standards, students are expected to collaborate and demonstrate critical thinking and problem-solving skills, all of which require they be actively engaged in their learning. Our findings show that less than 3 percent of middle school math assignments and less than 15 percent of middle school literacy assignments allowed for student choice and relevancy.

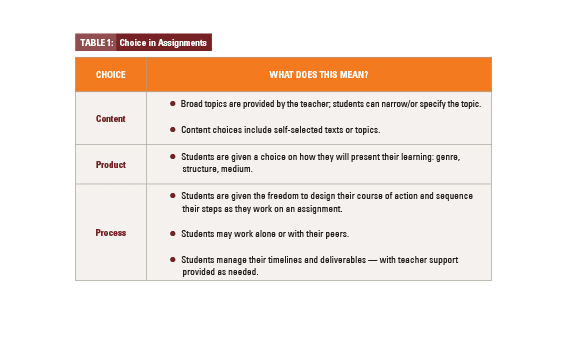

In “ Motivation and Engagement in Student Assignments: The Role of Choice and Relevancy ,” we explore how educators can bring choice and relevancy into their daily assignments. The authors explain how choice can and should be provided in terms of content, product, and process.

Teachers bring relevancy to assignments when they:

- Teach rigorous content using themes across disciplines, cultures, and generations; consider essential questions; and explore universal understandings

- Use real-world materials and events to explore salient topics

- Connect with the values, interests, and goals of their students

“In order to increase student motivation and engagement, students should be given meaningful choices in their learning, and tasks should be relevant, using real-world experiences and examples. As they work to motivate and engage students, educators should be cautious about using gimmicks or artificial techniques with unproven results. Rather, they should focus on connecting with students, bridging their known worlds with new concepts and ideas.”

—Joan Dabrowski, Ed.D , assistant superintendent for teaching and learning in the Wellesley Public Schools

There is clearly work to do if we are committed to the idea that student motivation and engagement are important and will lead to improved academic achievement. This begins, first and foremost, with knowing and valuing students.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Motivational Activities. Goal setting is often best supported through coaching. One model of goal setting conversation is the Auerbach GOOD coaching model (2015). It can be used for structuring coaching sessions in a way that progresses from goal setting and exploring options to action planning and accountability.

Kick off the school year or a new term with a care package. Student motivation will skyrocket when they get their hands on snacks, activities, and useful items that will be of use during academic lessons! Learn More: Rain And Pine. 16. Classroom Yoga. The effects of stress can be minimized when you encourage students to get active in class.

The Science of Motivation Explained. Goal-directed activities are started and sustained by motivation. "Motivational processes are personal/internal influences that lead to outcomes such as choice, effort, persistence, achievement, and environmental regulation" (Schunk & DiBenedetto, 2020). There are two types of motivation: intrinsic and ...

Motivation, both intrinsic and extrinsic, is a key factor in students' success at all stages of their education, and teachers can play a pivotal role in providing and encouraging that motivation in their students. ... For example, allowing students to choose the type of assignment they do or which problems to work on can give them a sense of ...

Extrinsic motivation tends to reduce long-term interest and effort in the topic at hand (Deci et al., 1999; Kohn, 2018; Wehe et al., 2015) and reduce creativity, as well (Hennessey, 2000). Research has found that motivation driven by extrinsic factors tends to lead to "decreased well-being" (Howard et al., 2021).

The students can also participate by suggesting their activities. As much as intrinsic motivation is concerned, the students should also have their motivations. Therefore, the following are motivation tips students should practice. Be perspective. Sometimes a student may feel a drag on their learning. It's normal for anyone, but students ...

You feel bored and lack motivation when you don't begin the work. Often starting something is the hardest thing. You'll realize it when you have to write assignments. Starting them is like a challenge, but you realize writing the other parts becomes fairly easy when you start writing. So, what you can do is create an outline for the assignment.

Nevertheless, because students are balancing multiple priorities (and multiple classes and assignments), it is worth considering key factors related to motivation. Wigfield and Eccles (2002) provides a wide-ranging overview of psychological theories of motivation that emphasize two key concepts: value and expectancy.

Perfectionism can destroy your motivation to do homework and keep you from starting important assignments. Some students procrastinate because they're waiting for the perfect time to start. Others do so because they want to get their homework done perfectly. But they know this isn't really possible - so they put off even getting started.

In "Motivation and Engagement in Student Assignments: The Role of Choice and Relevancy," we explore how educators can bring choice and relevancy into their daily assignments. The authors explain how choice can and should be provided in terms of content, product, and process. Teachers bring relevancy to assignments when they: