Advertisement

How to conduct systematic literature reviews in management research: a guide in 6 steps and 14 decisions

- Review Paper

- Open access

- Published: 12 May 2023

- Volume 17 , pages 1899–1933, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Philipp C. Sauer ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1823-0723 1 &

- Stefan Seuring ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4204-9948 2

23k Accesses

42 Citations

6 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

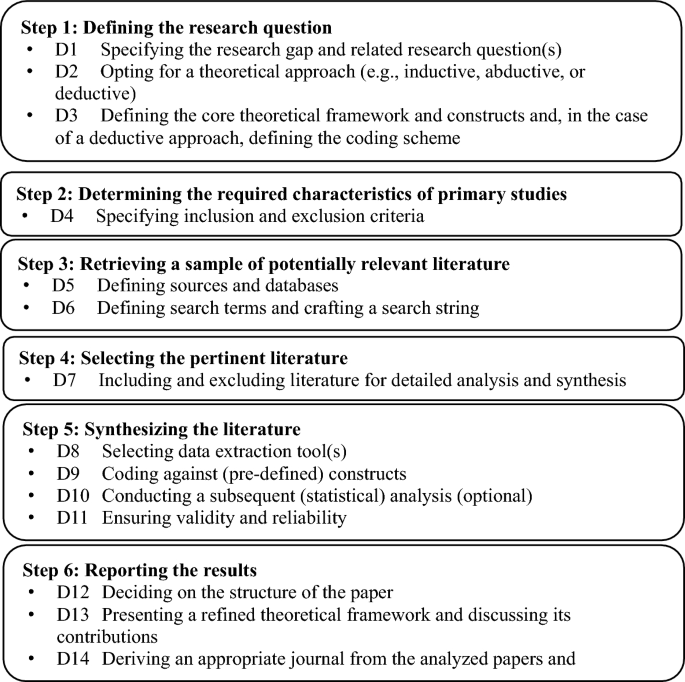

Systematic literature reviews (SLRs) have become a standard tool in many fields of management research but are often considerably less stringently presented than other pieces of research. The resulting lack of replicability of the research and conclusions has spurred a vital debate on the SLR process, but related guidance is scattered across a number of core references and is overly centered on the design and conduct of the SLR, while failing to guide researchers in crafting and presenting their findings in an impactful way. This paper offers an integrative review of the widely applied and most recent SLR guidelines in the management domain. The paper adopts a well-established six-step SLR process and refines it by sub-dividing the steps into 14 distinct decisions: (1) from the research question, via (2) characteristics of the primary studies, (3) to retrieving a sample of relevant literature, which is then (4) selected and (5) synthesized so that, finally (6), the results can be reported. Guided by these steps and decisions, prior SLR guidelines are critically reviewed, gaps are identified, and a synthesis is offered. This synthesis elaborates mainly on the gaps while pointing the reader toward the available guidelines. The paper thereby avoids reproducing existing guidance but critically enriches it. The 6 steps and 14 decisions provide methodological, theoretical, and practical guidelines along the SLR process, exemplifying them via best-practice examples and revealing their temporal sequence and main interrelations. The paper guides researchers in the process of designing, executing, and publishing a theory-based and impact-oriented SLR.

Similar content being viewed by others

Reporting reliability, convergent and discriminant validity with structural equation modeling: A review and best-practice recommendations

Research Methodology: An Introduction

RMSEA, CFI, and TLI in structural equation modeling with ordered categorical data: The story they tell depends on the estimation methods

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The application of systematic or structured literature reviews (SLRs) has developed into an established approach in the management domain (Kraus et al. 2020 ), with 90% of management-related SLRs published within the last 10 years (Clark et al. 2021 ). Such reviews help to condense knowledge in the field and point to future research directions, thereby enabling theory development (Fink 2010 ; Koufteros et al. 2018 ). SLRs have become an established method by now (e.g., Durach et al. 2017 ; Koufteros et al. 2018 ). However, many SLR authors struggle to efficiently synthesize and apply review protocols and justify their decisions throughout the review process (Paul et al. 2021 ) since only a few studies address and explain the respective research process and the decisions to be taken in this process. Moreover, the available guidelines do not form a coherent body of literature but focus on the different details of an SLR, while a comprehensive and detailed SLR process model is lacking. For example, Seuring and Gold ( 2012 ) provide some insights into the overall process, focusing on content analysis for data analysis without covering the practicalities of the research process in detail. Similarly, Durach et al. ( 2017 ) address SLRs from a paradigmatic perspective, offering a more foundational view covering ontological and epistemological positions. Durach et al. ( 2017 ) emphasize the philosophy of science foundations of an SLR. Although somewhat similar guidelines for SLRs might be found in the wider body of literature (Denyer and Tranfield 2009 ; Fink 2010 ; Snyder 2019 ), they often take a particular focus and are less geared toward explaining and reflecting on the single choices being made during the research process. The current body of SLR guidelines leaves it to the reader to find the right links among the guidelines and to justify their inconsistencies. This is critical since a vast number of SLRs are conducted by early-stage researchers who likely struggle to synthesize the existing guidance and best practices (Fisch and Block 2018 ; Kraus et al. 2020 ), leading to the frustration of authors, reviewers, editors, and readers alike.

Filling these gaps is critical in our eyes since researchers conducting literature reviews form the foundation of any kind of further analysis to position their research into the respective field (Fink 2010 ). So-called “systematic literature reviews” (e.g., Davis and Crombie 2001 ; Denyer and Tranfield 2009 ; Durach et al. 2017 ) or “structured literature reviews” (e.g., Koufteros et al. 2018 ; Miemczyk et al. 2012 ) differ from nonsystematic literature reviews in that the analysis of a certain body of literature becomes a means in itself (Kraus et al. 2020 ; Seuring et al. 2021 ). Although two different terms are used for this approach, the related studies refer to the same core methodological references that are also cited in this paper. Therefore, we see them as identical and abbreviate them as SLR.

There are several guidelines on such reviews already, which have been developed outside the management area (e.g. Fink 2010 ) or with a particular focus on one management domain (e.g., Kraus et al. 2020 ). SLRs aim at capturing the content of the field at a point in time but should also aim at informing future research (Denyer and Tranfield 2009 ), making follow-up research more efficient and productive (Kraus et al. 2021 ). Such standalone literature reviews would and should also prepare subsequent empirical or modeling research, but usually, they require far more effort and time (Fisch and Block 2018 ; Lim et al. 2022 ). To achieve this preparation, SLRs can essentially a) describe the state of the literature, b) test a hypothesis based on the available literature, c) extend the literature, and d) critique the literature (Xiao and Watson 2019 ). Beyond guiding the next incremental step in research, SLRs “may challenge established assumptions and norms of a given field or topic, recognize critical problems and factual errors, and stimulate future scientific conversations around that topic” (Kraus et al. 2022 , p. 2578). Moreover, they have the power to answer research questions that are beyond the scope of individual empirical or modeling studies (Snyder 2019 ) and to build, elaborate, and test theories beyond this single study scope (Seuring et al. 2021 ). These contributions of an SLR may be highly influential and therefore underline the need for high-quality planning, execution, and reporting of their process and details.

Regardless of the individual aims of standalone SLRs, their numbers have exponentially risen in the last two decades (Kraus et al. 2022 ) and almost all PhD or large research project proposals in the management domain include such a standalone SLR to build a solid foundation for their subsequent work packages. Standalone SLRs have thus become a key part of management research (Kraus et al. 2021 ; Seuring et al. 2021 ), which is also underlined by the fact that there are journals and special issues exclusively accepting standalone SLRs (Kraus et al. 2022 ; Lim et al. 2022 ).

However, SLRs require a commitment that is often comparable to an additional research process or project. Hence, SLRs should not be taken as a quick solution, as a simplistic, descriptive approach would usually not yield a publishable paper (see also Denyer and Tranfield 2009 ; Kraus et al. 2020 ).

Furthermore, as with other research techniques, SLRs are based on the rigorous application of rules and procedures, as well as on ensuring the validity and reliability of the method (Fisch and Block 2018 ; Seuring et al. 2021 ). In effect, there is a need to ensure “the same level of rigour to reviewing research evidence as should be used in producing that research evidence in the first place” (Davis and Crombie 2001 , p.1). This rigor holds for all steps of the research process, such as establishing the research question, collecting data, analyzing it, and making sense of the findings (Durach et al. 2017 ; Fink 2010 ; Seuring and Gold 2012 ). However, there is a high degree of diversity where some would be justified, while some papers do not report the full details of the research process. This lack of detail contrasts with an SLR’s aim of creating a valid map of the currently available research in the reviewed field, as critical information on the review’s completeness and potential reviewer biases cannot be judged by the reader or reviewer. This further impedes later replications or extensions of such reviews, which could provide longitudinal evidence of the development of a field (Denyer and Tranfield 2009 ; Durach et al. 2017 ). Against this observation, this paper addresses the following question:

Which decisions need to be made in an SLR process, and what practical guidelines can be put forward for making these decisions?

Answering this question, the key contributions of this paper are fourfold: (1) identifying the gaps in existing SLR guidelines, (2) refining the SLR process model by Durach et al. ( 2017 ) through 14 decisions, (3) synthesizing and enriching guidelines for these decisions, exemplifying the key decisions by means of best practice SLRs, and (4) presenting and discussing a refined SLR process model.

In some cases, we point to examples from operations and supply chain management. However, they illustrate the purposes discussed in the respective sections. We carefully checked that the arguments held for all fields of management-related research, and multiple examples from other fields of management were also included.

2 Identification of the need for an enriched process model, including a set of sequential decisions and their interrelations

In line with the exponential increase in SLR papers (Kraus et al. 2022 ), multiple SLR guidelines have recently been published. Since 2020, we have found a total of 10 papers offering guidelines on SLRs and other reviews for the field of management in general or some of its sub-fields. These guidelines are of double interest to this paper since we aim to complement them to fill the gap identified in the introduction while minimizing the doubling of efforts. Table 1 lists the 10 most recent guidelines and highlights their characteristics, research objectives, contributions, and how our paper aims to complement these previous contributions.

The sheer number and diversity of guideline papers, as well as the relevance expressed in them, underline the need for a comprehensive and exhaustive process model. At the same time, the guidelines take specific foci on, for example, updating earlier guidelines to new technological potentials (Kraus et al. 2020 ), clarifying the foundational elements of SLRs (Kraus et al. 2022 ) and proposing a review protocol (Paul et al. 2021 ) or the application and development of theory in SLRs (Seuring et al. 2021 ). Each of these foci fills an entire paper, while the authors acknowledge that much more needs to be considered in an SLR. Working through these most recent guidelines, it becomes obvious that the common paper formats in the management domain create a tension for guideline papers between elaborating on a) the SLR process and b) the details, options, and potentials of individual process steps.

Our analysis in Table 1 evidences that there are a number of rich contributions on aspect b), while the aspect a) of SLR process models has not received the same attention despite the substantial confusion of authors toward them (Paul et al. 2021 ). In fact, only two of the most recent guidelines approach SLR process models. First, Kraus et al. ( 2020 ) incrementally extended the 20-year-old Tranfield et al. ( 2003 ) three-stage model into four stages. A little later, Paul et al. ( 2021 ) proposed a three-stage (including six sub-stages) SPAR-4-SLR review protocol. It integrates the PRISMA reporting items (Moher et al. 2009 ; Page et al. 2021 ) that originate from clinical research to define 14 actions stating what items an SLR in management needs to report for reasons of validity, reliability, and replicability. Almost naturally, these 14 reporting-oriented actions mainly relate to the first SLR stage of “assembling the literature,” which accounts for nine of the 14 actions. Since this protocol is published in a special issue editorial, its presentation and elaboration are somewhat limited by the already mentioned word count limit. Nevertheless, the SPAR-4-SLR protocol provides a very useful checklist for researchers that enables them to include all data required to document the SLR and to avoid confusion from editors, reviewers, and readers regarding SLR characteristics.

Beyond Table 1 , Durach et al. ( 2017 ) synthesized six common SLR “steps” that differ only marginally in the delimitation of one step to another from the sub-stages of the previously mentioned SLR processes. In addition, Snyder ( 2019 ) proposed a process comprising four “phases” that take more of a bird’s perspective in addressing (1) design, (2) conduct, (3) analysis, and (4) structuring and writing the review. Moreover, Xiao and Watson ( 2019 ) proposed only three “stages” of (1) planning, (2) conducting, and (3) reporting the review that combines the previously mentioned conduct and the analysis and defines eight steps within them. Much in line with the other process models, the final reporting stage contains only one of the eight steps, leaving the reader somewhat alone in how to effectively craft a manuscript that contributes to the further development of the field.

In effect, the mentioned SLR processes differ only marginally, while the systematic nature of actions in the SPAR-4-SLR protocol (Paul et al. 2021 ) can be seen as a reporting must-have within any of the mentioned SLR processes. The similarity of the SLR processes is, however, also evident in the fact that they leave open how the SLR analysis can be executed, enriched, and reflected to make a contribution to the reviewed field. In contrast, this aspect is richly described in the other guidelines that do not offer an SLR process, leading us again toward the tension for guideline papers between elaborating on a) the SLR process and b) the details, options, and potentials of each process step.

To help (prospective) SLR authors successfully navigate this tension of existing guidelines, it is thus the ambition of this paper to adopt a comprehensive SLR process model along which an SLR project can be planned, executed, and written up in a coherent way. To enable this coherence, 14 distinct decisions are defined, reflected, and interlinked, which have to be taken across the different steps of the SLR process. At the same time, our process model aims to actively direct researchers to the best practices, tips, and guidance that previous guidelines have provided for individual decisions. We aim to achieve this by means of an integrative review of the relevant SLR guidelines, as outlined in the following section.

3 Methodology: an integrative literature review of guidelines for systematic literature reviews in management

It might seem intuitive to contribute to the debate on the “gold standard” of systematic literature reviews (Davis et al. 2014 ) by conducting a systematic review ourselves. However, there are different types of reviews aiming for distinctive contributions. Snyder ( 2019 ) distinguished between a) systematic, b) semi-systematic, and c) integrative (or critical) reviews, which aim for i) (mostly quantitative) synthesis and comparison of prior (primary) evidence, ii) an overview of the development of a field over time, and iii) a critique and synthesis of prior perspectives to reconceptualize or advance them. Each review team needs to position itself in such a typology of reviews to define the aims and scope of the review. To do so and structure the related research process, we adopted the four generic steps for an (integrative) literature review by Snyder ( 2019 )—(1) design, (2) conduct, (3) analysis, and (4) structuring and writing the review—on which we report in the remainder of this section. Since the last step is a very practical one that, for example, asks, “Is the contribution of the review clearly communicated?” (Snyder 2019 ), we will focus on the presentation of the method applied to the initial three steps:

(1) Regarding the design, we see the need for this study emerging from our experience in reviewing SLR manuscripts, supervising PhD students who, almost by default, need to prepare an SLR, and recurring discussions on certain decisions in the process of both. These discussions regularly left some blank or blurry spaces (see Table 1 ) that induced substantial uncertainty regarding critical decisions in the SLR process (Paul et al. 2021 ). To address this gap, we aim to synthesize prior guidance and critically enrich it, thus adopting an integrative approach for reviewing existing SLR guidance in the management domain (Snyder 2019 ).

(2) To conduct the review, we started collecting the literature that provided guidance on the individual SLR parts. We built on a sample of 13 regularly cited or very recent papers in the management domain. We started with core articles that we successfully used to publish SLRs in top-tier OSCM journals, such as Tranfield et al. ( 2003 ) and Durach et al. ( 2017 ), and we checked their references and papers that cited these publications. The search focus was defined by the following criteria: the articles needed to a) provide original methodological guidance for SLRs by providing new aspects of the guideline or synthesizing existing ones into more valid guidelines and b) focus on the management domain. Building on the nature of a critical or integrative review that does not require a full or representative sample (Snyder 2019 ), we limited the sample to the papers displayed in Table 2 that built the core of the currently applied SLR guidelines. In effect, we found 11 technical papers and two SLRs of SLRs (Carter and Washispack 2018 ; Seuring and Gold 2012 ). From the latter, we mainly analyzed the discussion and conclusion parts that explicitly developed guidance on conducting SLRs.

(3) For analyzing these papers, we first adopted the six-step SLR process proposed by Durach et al. ( 2017 , p.70), which they define as applicable to any “field, discipline or philosophical perspective”. The contrast between the six-step SLR process used for the analysis and the four-step process applied by ourselves may seem surprising but is justified by the use of an integrative approach. This approach differs mainly in retrieving and selecting pertinent literature that is key to SLRs and thus needs to be part of the analysis framework.

While deductively coding the sample papers against Durach et al.’s ( 2017 ), guidance in the six steps, we inductively built a set of 14 decisions presented in the right columns of Table 2 that are required to be made in any SLR. These decisions built a second and more detailed level of analysis, for which the single guidelines were coded as giving low, medium, or high levels of detail (see Table 3 ), which helped us identify the gaps in the current guidance papers and led our way in presenting, critically discussing, and enriching the literature. In effect, we see that almost all guidelines touch on the same issues and try to give a comprehensive overview. However, this results in multiple guidelines that all lack the space to go into detail, while only a few guidelines focus on filling a gap in the process. It is our ambition with this analysis to identify the gaps in the guidelines, thereby identifying a precise need for refinement, and to offer a first step into this refinement. Adopting advice from the literature sample, the coding was conducted by the entire author team (Snyder 2019 ; Tranfield et al. 2003 ) including discursive alignments of interpretation (Seuring and Gold 2012 ). This enabled a certain reliability and validity of the analysis by reducing the within-study and expectancy bias (Durach et al. 2017 ), while the replicability was supported by reporting the review sample and the coding results in Table 3 (Carter and Washispack 2018 ).

(4) For the writing of the review, we only pointed to the unusual structure of presenting the method without a theory section and then the findings in the following section. However, this was motivated by the nature of the integrative review so that the review findings at the same time represent the “state of the art,” “literature review,” or “conceptualization” sections of a paper.

4 Findings of the integrative review: presentation, critical discussion, and enrichment of prior guidance

4.1 the overall research process for a systematic literature review.

Even within our sample of only 13 guidelines, there are four distinct suggestions for structuring the SLR process. One of the earliest SLR process models was proposed by Tranfield et al. ( 2003 ) encompassing the three stages of (1) planning the review, (2) conducting a review, and (3) reporting and dissemination. Snyder ( 2019 ) proposed four steps employed in this study: (1) design, (2) conduct, (3) analysis, and (4) structuring and writing the review. Borrowing from content analysis guidelines, Seuring and Gold ( 2012 ) defined four steps: (1) material collection, (2) descriptive analysis, (3) category selection, and (4) material evaluation. Most recently Kraus et al. ( 2020 ) proposed four steps: (1) planning the review, (2) identifying and evaluating studies, (3) extracting and synthesizing data, and (4) disseminating the review findings. Most comprehensively, Durach et al. ( 2017 ) condensed prior process models into their generic six steps for an SLR. Adding the review of the process models by Snyder ( 2019 ) and Seuring and Gold ( 2012 ) to Durach et al.’s ( 2017 ) SLR process review of four papers, we support their conclusion of the general applicability of the six steps defined. Consequently, these six steps form the backbone of our coding scheme, as shown in the left column of Table 2 and described in the middle column.

As stated in Sect. 3 , we synthesized the review papers against these six steps but experienced that the papers were taking substantially different foci by providing rich details for some steps while largely bypassing others. To capture this heterogeneity and better operationalize the SLR process, we inductively introduced the right column, identifying 14 decisions to be made. These decisions are all elaborated in the reviewed papers but to substantially different extents, as the detailed coding results in Table 3 underline.

Mapping Table 3 for potential gaps in the existing guidelines, we found six decisions on which we found only low- to medium-level details, while high-detail elaboration was missing. These six decisions, which are illustrated in Fig. 1 , belong to three steps: 1: defining the research question, 5: synthesizing the literature, and 6: reporting the results. This result underscores our critique of currently unbalanced guidance that is, on the one hand, detailed on determining the required characteristics of primary studies (step 2), retrieving a sample of potentially relevant literature (step 3), and selecting the pertinent literature (step 4). On the other hand, authors, especially PhD students, are left without substantial guidance on the steps critical to publication. Instead, they are called “to go one step further … and derive meaningful conclusions” (Fisch and Block 2018 , p. 105) without further operationalizations on how this can be achieved; for example, how “meet the editor” conference sessions regularly cause frustration among PhDs when editors call for “new,” “bold,” and “relevant” research. Filling the gaps in the six decisions with best practice examples and practical experience is the main focus of this study’s contribution. The other eight decisions are synthesized with references to the guidelines that are most helpful and relevant for the respective step in our eyes.

The 6 steps and 14 decisions of the SLR process

4.2 Step 1: defining the research question

When initiating a research project, researchers make three key decisions.

Decision 1 considers the essential tasks of establishing a relevant and timely research question, but despite the importance of the decision, which determines large parts of further decisions (Snyder 2019 ; Tranfield et al. 2003 ), we only find scattered guidance in the literature. Hence, how can a research topic be specified to allow a strong literature review that is neither too narrow nor too broad? The latter is the danger in meta-reviews (i.e., reviews of reviews) (Aguinis et al. 2020 ; Carter and Washispack 2018 ; Kache and Seuring 2014 ). In this respect, even though the method would be robust, the findings would not be novel. In line with Carter and Washispack ( 2018 ), there should always be room for new reviews, yet over time, they must move from a descriptive overview of a field further into depth and provide detailed analyses of constructs. Clark et al. ( 2021 ) provided a detailed but very specific reflection on how they crafted a research question for an SLR and that revisiting the research question multiple times throughout the SLR process helps to coherently and efficiently move forward with the research. More generically, Kraus et al. ( 2020 ) listed six key contributions of an SLR that can guide the definition of the research question. Finally, Snyder ( 2019 ) suggested moving into more detail from existing SLRs and specified two main avenues for crafting an SLR research question that are either investigating the relationship among multiple effects, the effect of (a) specific variable(s), or mapping the evidence regarding a certain research area. For the latter, we see three possible alternative approaches, starting with a focus on certain industries. Examples are analyses of the food industry (Beske et al. 2014 ), retailing (Wiese et al. 2012 ), mining and minerals (Sauer and Seuring 2017 ), or perishable product supply chains (Lusiantoro et al. 2018 ) and traceability at the example of the apparel industry (Garcia-Torres et al. 2019 ). A second opportunity would be to assess the status of research in a geographical area that composes an interesting context from a research perspective, such as sustainable supply chain management (SSCM) in Latin America (Fritz and Silva 2018 ), yet this has to be justified explicitly, avoiding the fact that geographical focus is taken as the reason per se (e.g., Crane et al. 2016 ). A third variant addresses emerging issues, such as SCM, in a base-of-the-pyramid setting (Khalid and Seuring 2019 ) and the use of blockchain technology (Wang et al. 2019 ) or digital transformation (Hanelt et al. 2021 ). These approaches limit the reviewed field to enable a more contextualized analysis in which the novelty, continued relevance, or unjustified underrepresentation of the context can be used to specify a research gap and related research question(s). This also impacts the following decisions, as shown below.

Decision 2 concerns the option for a theoretical approach (i.e., the adoption of an inductive, abductive, or deductive approach) to theory building through the literature review. The review of previous guidance on this delivers an interesting observation. On the one hand, there are early elaborations on systematic reviews, realist synthesis, meta-synthesis, and meta-analysis by Tranfield et al. ( 2003 ) that are borrowing from the origins of systematic reviews in medical research. On the other hand, recent management-related guidelines largely neglect details of related decisions, but point out that SLRs are a suitable tool for theory building (Kraus et al. 2020 ). Seuring et al. ( 2021 ) set out to fill this gap and provided substantial guidance on how to use theory in SLRs to advance the field. To date, the option for a theoretical approach is only rarely made explicit, leaving the reader often puzzled about how advancement in theory has been crafted and impeding a review’s replicability (Seuring et al. 2021 ). Many papers still leave related choices in the dark (e.g., Rhaiem and Amara 2021 ; Rojas-Córdova et al. 2022 ) and move directly from the introduction to the method section.

In Decision 3, researchers need to adopt a theoretical framework (Durach et al. 2017 ) or at least a theoretical starting point, depending on the most appropriate theoretical approach (Seuring et al. 2021 ). Here, we find substantial guidance by Durach et al. ( 2017 ) that underlines the value of adopting a theoretical lens to investigate SCM phenomena and the literature. Moreover, the choice of a theoretical anchor enables a consistent definition and operationalization of constructs that are used to analyze the reviewed literature (Durach et al. 2017 ; Seuring et al. 2021 ). Hence, providing some upfront definitions is beneficial, clarifying what key terminology would be used in the subsequent paper, such as Devece et al. ( 2019 ) introduce their terminology on coopetition. Adding a practical hint beyond the elaborations of prior guidance papers for taking up established constructs in a deductive analysis (decision 2), there would be the question of whether these can yield interesting findings.

Here, it would be relevant to specify what kind of analysis is aimed for the SLR, where three approaches might be distinguished (i.e., bibliometric analysis, meta-analysis, and content analysis–based studies). Briefly distinguishing them, the core difference would be how many papers can be analyzed employing the respective method. Bibliometric analysis (Donthu et al. 2021 ) usually relies on the use of software, such as Biblioshiny, allowing the creation of figures on citations and co-citations. These figures enable the interpretation of large datasets in which several hundred papers can be analyzed in an automated manner. This allows for distinguishing among different research clusters, thereby following a more inductive approach. This would be contrasted by meta-analysis (e.g., Leuschner et al. 2013 ), where often a comparatively smaller number of papers is analyzed (86 in the respective case) but with a high number of observations (more than 17,000). The aim is to test for statistically significant correlations among single constructs, which requires that the related constructs and items be precisely defined (i.e., a clearly deductive approach to the analysis).

Content analysis is the third instrument frequently applied to data analysis, where an inductive or deductive approach might be taken (Seuring et al. 2021 ). Content-based analysis (see decision 9 in Sect. 4.6 ; Seuring and Gold 2012 ) is a labor-intensive step and can hardly be changed ex post. This also implies that only a certain number of papers might be analyzed (see Decision 6 in Sect. 4.5 ). It is advisable to adopt a wider set of constructs for the analysis stemming even from multiple established frameworks since it is difficult to predict which constructs and items might yield interesting insights. Hence, coding a more comprehensive set of items and dropping some in the process is less problematic than starting an analysis all over again for additional constructs and items. However, in the process of content analysis, such an iterative process might be required to improve the meaningfulness of the data and findings (Seuring and Gold 2012 ). A recent example of such an approach can be found in Khalid and Seuring ( 2019 ), building on the conceptual frameworks for SSCM of Carter and Rogers ( 2008 ), Seuring and Müller ( 2008 ), and Pagell and Wu ( 2009 ). This allows for an in-depth analysis of how SSCM constructs are inherently referred to in base-of-the-pyramid-related research. The core criticism and limitation of such an approach is the random and subjectively biased selection of frameworks for the purpose of analysis.

Beyond the aforementioned SLR methods, some reviews, similar to the one used here, apply a critical review approach. This is, however, nonsystematic, and not an SLR; thus, it is beyond the scope of this paper. Interested readers can nevertheless find some guidance on critical reviews in the available literature (e.g., Kraus et al. 2022 ; Snyder 2019 ).

4.3 Step 2: determining the required characteristics of primary studies

After setting the stage for the review, it is essential to determine which literature is to be reviewed in Decision 4. This topic is discussed by almost all existing guidelines and will thus only briefly be discussed here. Durach et al. ( 2017 ) elaborated in great detail on defining strict inclusion and exclusion criteria that need to be aligned with the chosen theoretical framework. The relevant units of analysis need to be specified (often a single paper, but other approaches might be possible) along with suitable research methods, particularly if exclusively empirical studies are reviewed or if other methods are applied. Beyond that, they elaborated on potential quality criteria that should be applied. The same is considered by a number of guidelines that especially draw on medical research, in which systematic reviews aim to pool prior studies to infer findings from their total population. Here, it is essential to ensure the exclusion of poor-quality evidence that would lower the quality of the review findings (Mulrow 1987 ; Tranfield et al. 2003 ). This could be ensured by, for example, only taking papers from journals listed on the Web of Science or Scopus or journals listed in quartile 1 of Scimago ( https://www.scimagojr.com/ ), a database providing citation and reference data for journals.

The selection of relevant publication years should again follow the purpose of the study defined in Step 1. As such, there might be a justified interest in the wide coverage of publication years if a historical perspective is taken. Alternatively, more contemporary developments or the analysis of very recent issues can justify the selection of very few years of publication (e.g., Kraus et al. 2022 ). Again, it is hard to specify a certain time period covered, but if developments of a field should be analyzed, a five-year period might be a typical lower threshold. On current topics, there is often a trend of rising publishing numbers. This scenario implies the rising relevance of a topic; however, this should be treated with caution. The total number of papers published per annum has increased substantially in recent years, which might account for the recently heightened number of papers on a certain topic.

4.4 Step 3: retrieving a sample of potentially relevant literature

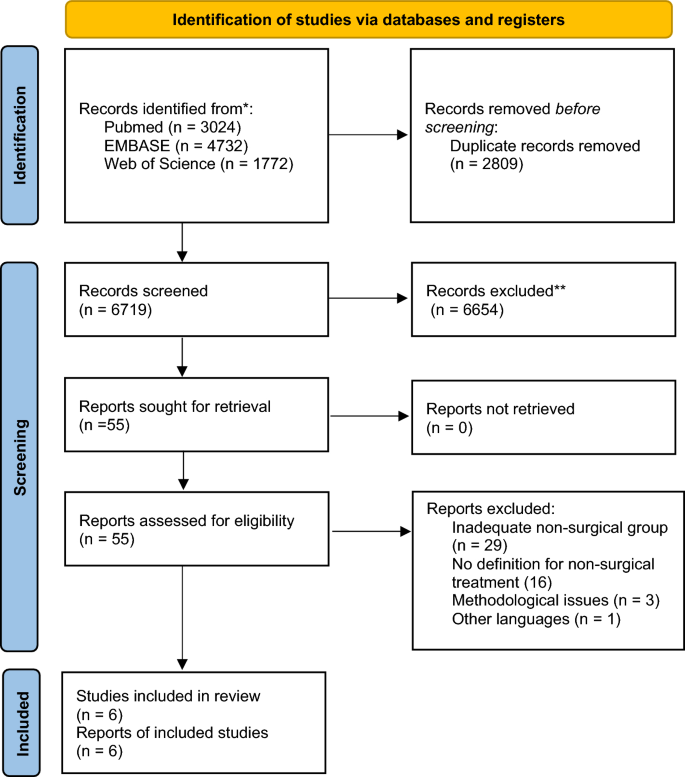

After defining the required characteristics of the literature to be reviewed, the literature needs to be retrieved based on two decisions. Decision 5 concerns suitable literature sources and databases that need to be defined. Turning to Web of Science or Scopus would be two typical options found in many of the examples mentioned already (see also detailed guidance by Paul and Criado ( 2020 ) as well as Paul et al. ( 2021 )). These databases aggregate many management journals, and a typical argument for turning to the Web of Science database is the inclusion of impact factors, as they indicate a certain minimum quality of the journal (Sauer and Seuring 2017 ). Additionally, Google Scholar is increasingly mentioned as a usable search engine, often providing higher numbers of search results than the mentioned databases (e.g., Pearce 2018 ). These results often entail duplicates of articles from multiple sources or versions of the same article, as well as articles in predatory journals (Paul et al. 2021 ). Therefore, we concur with Paul et al. ( 2021 ) who underline the quality assurance mechanisms in Web of Science and Scopus, making them preferred databases for the literature search. From a practical perspective, it needs to be mentioned that SLRs in management mainly rely on databases that are not free to use. Against this limitation, Pearce ( 2018 ) provided a list of 20 search engines that are free of charge and elaborated on their advantages and disadvantages. Due to the individual limitations of the databases, it is advisable to use a combination of them (Kraus et al. 2020 , 2022 ) and build a consolidated sample by screening the papers found for duplicates, as regularly done in SLRs.

This decision also includes the choice of the types of literature to be analyzed. Typically, journal papers are selected, ensuring that the collected papers are peer-reviewed and have thus undergone an academic quality management process. Meanwhile, conference papers are usually avoided since they are often less mature and not checked for quality (e.g., Seuring et al. 2021 ). Nevertheless, for emerging topics, it might be too restrictive to consider only peer-reviewed journal articles and limit the literature to only a few references. Analyzing such rapidly emerging topics is relevant for timely and impact-oriented research and might justify the selection of different sources. Kraus et al. ( 2020 ) provided a discussion on the use of gray literature (i.e., nonacademic sources), and Sauer ( 2021 ) provided an example of a review of sustainability standards from a management perspective to derive implications for their application by managers on the one hand and for enhancing their applicability on the other hand.

Another popular way to limit the review sample is the restriction to a certain list of journals (Kraus et al. 2020 ; Snyder 2019 ). While this is sometimes favored by highly ranked journals, Carter and Washispack ( 2018 ), for example, found that many pertinent papers are not necessarily published in journals within the field. Webster and Watson ( 2002 ) quite tellingly cited a reviewer labeling the selection of top journals as an unjustified excuse for investigating the full body of relevant literature. Both aforementioned guidelines thus discourage the restriction to particular journals, a guidance that we fully support.

However, there is an argument to be made supporting the exclusion of certain lower-ranked journals. This can be done, for example, by using Scimago Journal quartiles ( www.scimagojr.com , last accessed 13. of April 2023) and restricting it to journals in the first quartile (e.g., Yavaprabhas et al. 2022 ). Other papers (e.g., Kraus et al. 2021 ; Rojas-Córdova et al. 2022 ) use certain journal quality lists to limit their sample. However, we argue for a careful check by the authors against the topic reviewed regarding what would be included and excluded.

Decision 6 entails the definition of search terms and a search string to be applied in the database just chosen. The search terms should reflect the aims of the review and the exclusion criteria that might be derived from the unit of analysis and the theoretical framework (Durach et al. 2017 ; Snyder 2019 ). Overall, two approaches to keywords can be observed. First, some guides suggest using synonyms of the key terms of interest (e.g., Durach et al. 2017 ; Kraus et al. 2020 ) in order to build a wide baseline sample that will be condensed in the next step. This is, of course, especially helpful if multiple terms delimitate a field together or different synonymous terms are used in parallel in different fields or journals. Empirical journals in supply chain management, for example, use the term “multiple supplier tiers ” (e.g., Tachizawa and Wong 2014 ), while modeling journals in the same field label this as “multiple supplier echelons ” (e.g., Brandenburg and Rebs 2015 ). Second, in some cases, single keywords are appropriate for capturing a central aspect or construct of a field if the single keyword has a global meaning tying this field together. This approach is especially relevant to the study of relatively broad terms, such as “social media” (Lim and Rasul 2022 ). However, this might result in very high numbers of publications found and therefore requires a purposeful combination with other search criteria, such as specific journals (Kraus et al. 2021 ; Lim et al. 2021 ), publication dates, article types, research methods, or the combination with keywords covering domains to which the search is aimed to be specified.

Since SLRs are often required to move into detail or review the intersections of relevant fields, we recommend building groups of keywords (single terms or multiple synonyms) for each field to be connected that are coupled via Boolean operators. To determine when a point of saturation for a keyword group is reached, one could monitor the increase in papers found in a database when adding another synonym. Once the increase is significantly decreasing or even zeroing, saturation is reached (Sauer and Seuring 2017 ). The keywords themselves can be derived from the list of keywords of influential publications in the field, while attention should be paid to potential synonyms in neighboring fields (Carter and Washispack 2018 ; Durach et al. 2017 ; Kraus et al. 2020 ).

4.5 Step 4: selecting the pertinent literature

The inclusion and exclusion criteria (Decision 6) are typically applied in Decision 7 in a two-stage process, first on the title, abstract, and keywords of an article before secondly applying them to the full text of the remaining articles (see also Kraus et al. 2020 ; Snyder 2019 ). Beyond this, Durach et al. ( 2017 ) underlined that the pertinence of the publication regarding units of analysis and the theoretical framework needs to be critically evaluated in this step to avoid bias in the review analysis. Moreover, Carter and Washispack ( 2018 ) requested the publication of the included and excluded sources to ensure the replicability of Steps 3 and 4. This can easily be done as an online supplement to an eventually published review article.

Nevertheless, the question remains: How many papers justify a literature review? While it is hard to specify how many papers comprise a body of literature, there might be certain thresholds for which Kraus et al. ( 2020 ) provide a useful discussion. As a rough guide, more than 50 papers would usually make a sound starting point (see also Paul and Criado 2020 ), while there are SLRs on emergent topics, such as multitier supply chain management, where 39 studies were included (Tachizawa and Wong 2014 ). An SLR on “learning from innovation failures” builds on 36 papers (Rhaiem and Amara 2021 ), which we would see as the lower threshold. However, such a low number should be an exception, and anything lower would certainly trigger the following question: Why is a review needed? Meanwhile, there are also limits on how many papers should be reviewed. While there are cases with 191 (Seuring and Müller 2008 ), 235 (Rojas-Córdova et al. 2022 ), or up to nearly 400 papers reviewed (Spens and Kovács 2006 ), these can be regarded as upper thresholds. Over time, similar topics seem to address larger datasets.

4.6 Step 5: synthesizing the literature

Before synthesizing the literature, Decision 8 considers the selection of a data extraction tool for which we found surprisingly little guidance. Some guidance is given on the use of cloud storage to enable remote team work (Clark et al. 2021 ). Beyond this, we found that SLRs have often been compiled with marked and commented PDFs or printed papers that were accompanied by tables (Kraus et al. 2020 ) or Excel sheets (see also the process tips by Clark et al. 2021 ). This sheet tabulated the single codes derived from the theoretical framework (Decision 3) and the single papers to be reviewed (Decision 7) by crossing out individual cells, signaling the representation of a particular code in a particular paper. While the frequency distribution of the codes is easily compiled from this data tool, the related content needs to be looked at in the papers in a tedious back-and-forth process. Beyond that, we would strongly recommend using data analysis software, such as MAXQDA or NVivo. Such programs enable the import of literature in PDF format and the automatic or manual coding of text passages, their comparison, and tabulation. Moreover, there is a permanent and editable reference of the coded text to a code. This enables a very quick compilation of content summaries or statistics for single codes and the identification of qualitative and quantitative links between codes and papers.

All the mentioned data extraction or data processing tools require a license and therefore are not free of cost. While many researchers may benefit from national or institutional subscriptions to these services, others may not. As a potential alternative, Pearce ( 2018 ) proposed a set of free open-source software (FOSS), including an elaboration on how they can be combined to perform an SLR. He also highlighted that both free and proprietary solutions have advantages and disadvantages that are worthwhile for those who do not have the required tools provided by their employers or other institutions they are members of. The same may apply to the literature databases used for the literature acquisition in Decision 5 (Pearce 2018 ).

Moreover, there is a link to Step 1, Decision 3, where bibliometric reviews and meta-analyses were mentioned. These methods, which are alternatives to content analysis–based approaches, have specific demands, so specific tools would be appropriate, such as the Biblioshiny software or VOSviewer. As we will point out for all decisions, there is a high degree of interdependence among the steps and decisions made.

Decision 9 looks at conducting the data analysis, such as coding against (pre-defined) constructs, in SLRs that rely, in most cases, on content analysis. Seuring and Gold ( 2012 ) elaborated in detail on its characteristics and application in SLRs. As this paper also explains the process of qualitative content analysis in detail, repetition is avoided here, but a summary is offered. Since different ways exist to conduct a content analysis, it is even more important to explain and justify, for example, the choice of an inductive or deductive approach (see Decision 2). In several cases, analytic variables are applied on the go, so there is no theory-based introduction of related constructs. However, to ensure the validity and replicability of the review (see Decision 11), it is necessary to explicitly define all the variables and codes used to analyze and synthesize the reviewed material (Durach et al. 2017 ; Seuring and Gold 2012 ). To build a valid framework as the SLR outcome, it is vital to ensure that the constructs used for the data analysis are sufficiently defined, mutually exclusive, and comprehensively exhaustive. For meta-analysis, the predefined constructs and items would demand quantitative coding so that the resulting data could be analyzed using statistical software tools such as SPSS or R (e.g., Xiao and Watson 2019 ). Pointing to bibliometric analysis again, the respective software would be used for data analysis, yielding different figures and paper clusters, which would then require interpretation (e.g., Donthu et al. 2021 ; Xiao and Watson 2019 ).

Decision 10, on conducting subsequent statistical analysis, considers follow-up analysis of the coding results. Again, this is linked to the chosen SLR method, and a bibliographic analysis will require a different statistical analysis than a content analysis–based SLR (e.g., Lim et al. 2022 ; Xiao and Watson 2019 ). Beyond the use of content analysis and the qualitative interpretation of its results, applying contingency analysis offers the opportunity to quantitatively assess the links among constructs and items. It provides insights into which items are correlated with each other without implying causality. Thus, the interpretation of the findings must explain the causality behind the correlations between the constructs and the items. This must be based on sound reasoning and linking the findings to theoretical arguments. For SLRs, there have recently been two kinds of applications of contingency analysis, differentiated by unit of analysis. De Lima et al. ( 2021 ) used the entire paper as the unit of analysis, deriving correlations on two constructs that were used together in one paper. This is, of course, subject to critique as to whether the constructs really represent correlated content. Moving a level deeper, Tröster and Hiete ( 2018 ) used single-text passages on one aspect, argument, or thought as the unit of analysis. Such an approach is immune against the critique raised before and can yield more valid statistical support for thematic analysis. Another recent methodological contribution employing the same contingency analysis–based approach was made by Siems et al. ( 2021 ). Their analysis employs constructs from SSCM and dynamic capabilities. Employing four subsets of data (i.e., two time periods each in the food and automotive industries), they showed that the method allows distinguishing among time frames as well as among industries.

However, the unit of analysis must be precisely explained so that the reader can comprehend it. Both examples use contingency analysis to identify under-researched topics and develop them into research directions whose formulation represents the particular aim of an SLR (Paul and Criado 2020 ; Snyder 2019 ). Other statistical tools might also be applied, such as cluster analysis. Interestingly, Brandenburg and Rebs ( 2015 ) applied both contingency and cluster analyses. However, the authors stated that the contingency analysis did not yield usable results, so they opted for cluster analysis. In effect, Brandenburg and Rebs ( 2015 ) added analytical depth to their analysis of model types in SSCM by clustering them against the main analytical categories of content analysis. In any case, the application of statistical tools needs to fit the study purpose (Decision 1) and the literature sample (Decision 7), just as in their more conventional applications (e.g., in empirical research processes).

Decision 11 regards the additional consideration of validity and reliability criteria and emphasizes the need for explaining and justifying the single steps of the research process (Seuring and Gold 2012 ), much in line with other examples of research (Davis and Crombie 2001 ). This is critical to underlining the quality of the review but is often neglected in many submitted manuscripts. In our review, we find rich guidance on this decision, to which we want to guide readers (see Table 3 ). In particular, Durach et al. ( 2017 ) provide an entire section of biases and what needs to be considered and reported on them. Moreover, Snyder ( 2019 ) regularly reflects on these issues in her elaborations. This rich guidance elaborates on how to ensure the quality of the individual steps of the review process, such as sampling, study inclusion and exclusion, coding, synthesizing, and more practical issues, including team composition and teamwork organization, which are discussed in some guidelines (e.g., Clark et al. 2021 ; Kraus et al. 2020 ). We only want to underline that the potential biases are, of course, to be seen in conjunction with Decisions 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, and 10. These decisions and the elaboration by Durach et al. ( 2017 ) should provide ample points of reflection that, however, many SLR manuscripts fail to address.

4.7 Step 6: reporting the results

In the final step, there are three decisions on which there is surprisingly little guidance, although reviews often fail in this critical part of the process (Kraus et al. 2020 ). The reviewed guidelines discuss the presentation almost exclusively, while almost no guidance is given on the overall paper structure or the key content to be reported.

Consequently, the first choice to be made in Decision 12 is regarding the paper structure. We suggest following the five-step logic of typical research papers (see also Fisch and Block 2018 ) and explaining only a few points in which a difference from other papers is seen.

(1) Introduction: While the introduction would follow a conventional logic of problem statement, research question, contribution, and outline of the paper (see also Webster and Watson 2002 ), the next parts might depend on the theoretical choices made in Decision 2.

(2) Literature review section: If deductive logic is taken, the paper usually has a conventional flow. After the introduction, the literature review section covers the theoretical background and the choice of constructs and variables for the analysis (De Lima et al. 2021 ; Dieste et al. 2022 ). To avoid confusion in this section with the literature review, its labeling can also be closer to the reviewed object.

If an inductive approach is applied, it might be challenging to present the theoretical basis up front, as the codes emerge only from analyzing the material. In this case, the theory section might be rather short, concentrating on defining the core concepts or terms used, for example, in the keyword-based search for papers. The latter approach is exemplified by the study at hand, which presents a short review of the available literature in the introduction and the first part of the findings. However, we do not perform a systematic but integrative review, which allows for more freedom and creativity (Snyder 2019 ).

(3) Method section: This section should cover the steps and follow the logic presented in this paper or any of the reviewed guidelines so that the choices made during the research process are transparently disclosed (Denyer and Tranfield 2009 ; Paul et al. 2021 ; Xiao and Watson 2019 ). In particular, the search for papers and their selection requires a sound explanation of each step taken, including the provision of reasons for the delimitation of the final paper sample. A stage that is often not covered in sufficient detail is data analysis (Seuring and Gold 2012 ). This also needs to be outlined so that the reader can comprehend how sense has been made of the material collected. Overall, the demands for SLR papers are similar to case studies, survey papers, or almost any piece of empirical research; thus, each step of the research process needs to be comprehensively described, including Decisions 4–10. This comprehensiveness must also include addressing measures for validity and reliability (see Decision 11) or other suitable measures of rigor in the research process since they are a critical issue in literature reviews (Durach et al. 2017 ). In particular, inductively conducted reviews are prone to subjective influences and thus require sound reporting of design choices and their justification.

(4) Findings: The findings typically start with a descriptive analysis of the literature covered, such as journals, distribution across years, or (empirical) methods applied (Tranfield et al. 2003 ). For modeling-related reviews, classifying papers against the approach chosen is a standard approach, but this can often also serve as an analytic category that provides detailed insights. The descriptive analysis should be kept short since a paper only presenting descriptive findings will not be of great interest to other researchers due to the missing contribution (Snyder 2019 ). Nevertheless, there are opportunities to provide interesting findings in the descriptive analysis. Beyond a mere description of the distributions of the single results, such as the distribution of methods used in the sample, authors should combine analytical categories to derive more detailed insights (see also Tranfield et al. 2003 ). The distribution of methods used might well be combined with the years of publication to identify and characterize different phases in the development of a field of research or its maturity. Moreover, there could be value in the analysis of theories applied in the review sample (e.g., Touboulic and Walker 2015 ; Zhu et al. 2022 ) and in reflecting on the interplay of different qualitative and quantitative methods in spurring the theoretical development of the reviewed field. This could yield detailed insights into methodological as well as theoretical gaps, and we would suggest explicitly linking the findings of such analyses to the research directions that an SLR typically provides. This link could help make the research directions much more tangible by giving researchers a clear indication of how to follow up on the findings, as, for example, done by Maestrini et al. ( 2017 ) or Dieste et al. ( 2022 ). In contrast to the mentioned examples of an actionable research agenda, a typical weakness of premature SLR manuscripts is that they ask rather superficially for more research in the different aspects they reviewed but remain silent about how exactly this can be achieved.

We would thus like to encourage future SLR authors to systematically investigate the potential to combine two categories of descriptive analysis to move this section of the findings to a higher level of quality, interest, and relevance. The same can, of course, be done with the thematic findings, which comprise the second part of this section.

Moving into the thematic analysis, we have already reached Decision 13 on the presentation of the refined theoretical framework and the discussion of its contents. A first step might present the frequencies of the codes or constructs applied in the analysis. This allows the reader to understand which topics are relevant. If a rather small body of literature is analyzed, tables providing evidence on which paper has been coded for which construct might be helpful in improving the transparency of the research process. Tables or other forms of visualization might help to organize the many codes soundly (see also Durach et al. 2017 ; Paul and Criado 2020 ; Webster and Watson 2002 ). These findings might then lead to interpretation, for which it is necessary to extract meaning from the body of literature and present it accordingly (Snyder 2019 ). To do so, it might seem needless to say that the researchers should refer back to Decisions 1, 2, and 3 taken in Step 1 and their justifications. These typically identify the research gap to be filled, but after the lengthy process of the SLR, the authors often fail to step back from the coding results and put them into a larger perspective against the research gap defined in Decision 1 (see also Clark et al. 2021 ). To support this, it is certainly helpful to illustrate the findings in a figure or graph presenting the links among the constructs and items and adding causal reasoning to this (Durach et al. 2017 ; Paul and Criado 2020 ), such as the three figures by Seuring and Müller ( 2008 ) or other examples by De Lima et al. ( 2021 ) or Tipu ( 2022 ). This presentation should condense arguments made in the assessed literature but should also chart the course for future research. It will be these parts of the paper that are decisive for a strong SLR paper.

Moreover, some guidelines define the most fruitful way of synthesizing the findings as concept-centric synthesis (Clark et al. 2021 ; Fisch and Block 2018 ; Webster and Watson 2002 ). As presented in the previous sentence, the presentation of the review findings is centered on the content or concept of “concept-centric synthesis.” It is accompanied by a reference to all or the most relevant literature in which the concept is evident. Contrastingly, Webster and Watson ( 2002 ) found that author-centric synthesis discusses individual papers and what they have done and found (just like this sentence here). They added that this approach fails to synthesize larger samples. We want to note that we used the latter approach in some places in this paper. However, this aims to actively refer the reader to these studies, as they stand out from our relatively small sample. Beyond this, we want to link back to Decision 3, the selection of a theoretical framework and constructs. These constructs, or the parts of a framework, can also serve to structure the findings section by using them as headlines for subsections (Seuring et al. 2021 ).

Last but not least, there might even be cases where core findings and relationships might be opposed, and alternative perspectives could be presented. This would certainly be challenging to argue for but worthwhile to do in order to drive the reviewed field forward. A related example is the paper by Zhu et al. ( 2022 ), who challenged the current debate at the intersection of blockchain applications and supply chain management and pointed to the limited use of theoretical foundations for related analysis.

(5) Discussion and Conclusion: The discussion needs to explain the contribution the paper makes to the extant literature, that is, which previous findings or hypotheses are supported or contradicted and which aspects of the findings are particularly interesting for the future development of the reviewed field. This is in line with the content required in the discussion sections of any other paper type. A typical structure might point to the contribution and put it into perspective with already existing research. Further, limitations should be addressed on both the theoretical and methodological sides. This elaboration of the limitations can be coupled with the considerations of the validity and reliability of the study in Decision 11. The implications for future research are a core aim of an SLR (Clark et al. 2021 ; Mulrow 1987 ; Snyder 2019 ) and should be addressed in a further part of the discussion section. Recently, a growing number of literature reviews have also provided research questions for future research that provide a very concrete and actionable output of the SLR (e.g. Dieste et al. 2022 ; Maestrini et al. 2017 ). Moreover, we would like to reiterate our call to clearly link the research implications to the SLR findings, which helps the authors craft more tangible research directions and helps the reader to follow the authors’ interpretation. Literature review papers are usually not strongly positioned toward managerial implications, but even these implications might be included.

As a kind of normal demand, the conclusion should provide an answer to the research question put forward in the introduction, thereby closing the cycle of arguments made in the paper.

Although all the works seem to be done when the paper is written and the contribution is fleshed out, there is still one major decision to be made. Decision 14 concerns the identification of an appropriate journal for submission. Despite the popularity of the SLR method, a rising number of journals explicitly limit the number of SLRs published by them. Moreover, there are only two guidelines elaborating on this decision, underlining the need for the following considerations.

Although it might seem most attractive to submit the paper to the highest-ranking journal for the reviewed topic, we argue for two critical and review-related decisions to be made during the research process that influence whether the paper fits a certain outlet:

The theoretical foundation of the SLR (Decision 3) usually relates to certain journals in which it is published or discussed. If a deductive approach was taken, the journals in which the foundational papers were published might be suitable since the review potentially contributes to the further validation or refinement of the frameworks. Overall, we need to keep in mind that a paper needs to be added to a discussion in the journal, and this can be based on the theoretical framework or the reviewed papers, as shown below.

Appropriate journals for publication can be derived from the analyzed journal papers (Decision 7) (see also Paul and Criado 2020 ). This allows for an easy link to the theoretical debate in the respective journal by submitting it. This choice is identifiable in most of the papers mentioned in this paper and is often illustrated in the descriptive analysis.

If the journal chosen for the submission was neither related to the theoretical foundation nor overly represented in the body of literature analyzed, an explicit justification in the paper itself might be needed. Alternatively, an explanation might be provided in the letter to the editor when submitting the paper. If such a statement is not presented, the likelihood of it being transferred into the review process and passing it is rather low. Finally, we want to refer readers interested in the specificities of the publication-related review process of SLRs to Webster and Watson ( 2002 ), who elaborated on this for Management Information Systems Quarterly.

5 Discussion and conclusion

Critically reviewing the currently available SLR guidelines in the management domain, this paper synthesizes 14 key decisions to be made and reported across the SLR research process. Guidelines are presented for each decision, including tasks that assist in making sound choices to complete the research process and make meaningful contributions. Applying these guidelines should improve the rigor and robustness of many review papers and thus enhance their contributions. Moreover, some practical hints and best-practice examples are provided on issues that unexperienced authors regularly struggle to present in a manuscript (Fisch and Block 2018 ) and thus frustrate reviewers, readers, editors, and authors alike.

Strikingly, the review of prior guidelines reported in Table 3 revealed their focus on the technical details that need to be reported in any SLR. Consequently, our discipline has come a long way in crafting search strings, inclusion, and exclusion criteria, and elaborating on the validity and reliability of an SLR. Nevertheless, we left critical areas underdeveloped, such as the identification of relevant research gaps and questions, data extraction tools, analysis of the findings, and a meaningful and interesting reporting of the results. Our study contributes to filling these gaps by providing operationalized guidance to SLR authors, especially early-stage researchers who craft SLRs at the outset of their research journeys. At the same time, we need to underline that our paper is, of course, not the only useful reference for SLR authors. Instead, the readers are invited to find more guidance on the many aspects to consider in an SLR in the references we provide within the single decisions, as well as in Tables 1 and 2 . The tables also identify the strongholds of other guidelines that our paper does not want to replace but connect and extend at selected occasions, especially in SLR Steps 5 and 6.

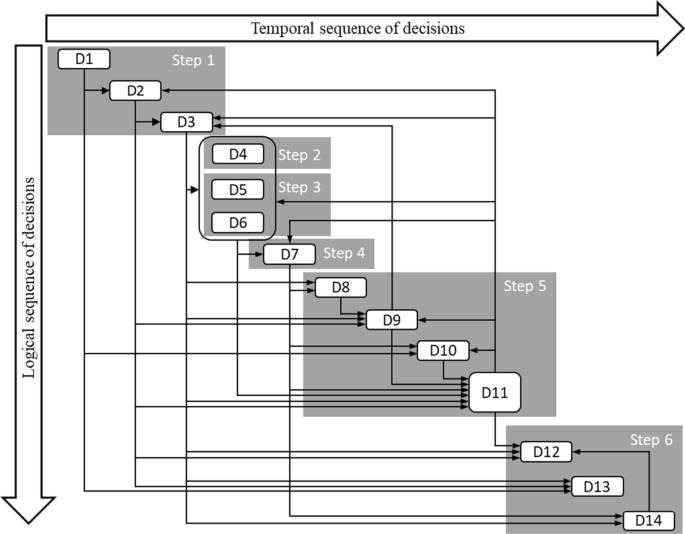

The findings regularly underline the interconnection of the 14 decisions identified and discussed in this paper. We thus support Tranfield et al. ( 2003 ) who requested a flexible approach to the SLR while clearly reporting all design decisions and reflecting their impacts. In line with the guidance synthesized in this review, and especially Durach et al. ( 2017 ), we also present a refined framework in Figs. 1 and 2 . It specifically refines the original six-step SLR process by Durach et al. ( 2017 ) in three ways:

Enriched six-step process including the core interrelations of the 14 decisions

First, we subdivided the six steps into 14 decisions to enhance the operationalization of the process and enable closer guidance (see Fig. 1 ). Second, we added a temporal sequence to Fig. 2 by positioning the decisions from left to right according to this temporal sequence. This is based on systematically reflecting on the need to finish one decision before the following. If this need is evident, the following decision moves to the right; if not, the decisions are positioned below each other. Turning to Fig. 2 , it becomes evident that Step 2, “determining the required characteristics of primary studies,” and Step 3, “retrieving a sample of potentially relevant literature,” including their Decisions 4–6, can be conducted in an iterative manner. While this contrasts with the strict division of the six steps by Durach et al. ( 2017 ), it supports other guidance that suggests running pilot studies to iteratively define the literature sample, its sources, and characteristics (Snyder 2019 ; Tranfield et al. 2003 ; Xiao and Watson 2019 ). While this insight might suggest merging Steps 2 and 3, we refrain from this superficial change and building yet another SLR process model. Instead, we prefer to add detail and depth to Durach et al.’s ( 2017 ) model.

(Decisions: D1: specifying the research gap and related research question, D2: opting for a theoretical approach, D3: defining the core theoretical framework and constructs, D4: specifying inclusion and exclusion criteria, D5: defining sources and databases, D6: defining search terms and crafting a search string, D7: including and excluding literature for detailed analysis and synthesis, D8: selecting data extraction tool(s), D9: coding against (pre-defined) constructs, D10: conducting a subsequent (statistical) analysis (optional), D11: ensuring validity and reliability, D12: deciding on the structure of the paper, D13: presenting a refined theoretical framework and discussing its contents, and D14: deriving an appropriate journal from the analyzed papers).

This is also done through the third refinement, which underlines which previous or later decisions need to be considered within each single decision. Such a consideration moves beyond the mere temporal sequence of steps and decisions that does not reflect the full complexity of the SLR process. Instead, its focus is on the need to align, for example, the conduct of the data analysis (Decision 9) with the theoretical approach (Decision 2) and consequently ensure that the chosen theoretical framework and the constructs (Decision 3) are sufficiently defined for the data analysis (i.e., mutually exclusive and comprehensively exhaustive). The mentioned interrelations are displayed in Fig. 2 by means of directed arrows from one decision to another. The underlying explanations can be found in the earlier paper sections by searching for the individual decisions in the text on the impacted decisions. Overall, it is unsurprising to see that the vast majority of interrelations are directed from the earlier to the later steps and decisions (displayed through arrows below the diagonal of decisions), while only a few interrelations are inverse.

Combining the first refinement of the original framework (defining the 14 decisions) and the third refinement (revealing the main interrelations among the decisions) underlines the contribution of this study in two main ways. First, the centrality of ensuring validity and reliability (Decision 11) is underlined. It becomes evident that considerations of validity and reliability are central to the overall SLR process since all steps before the writing of the paper need to be revisited in iterative cycles through Decision 11. Any lack of related considerations will most likely lead to reviewer critique, putting the SLR publication at risk. On the positive side of this centrality, we also found substantial guidance on this issue. In contrast, as evidenced in Table 3 , there is a lack of prior guidance on Decisions 1, 8, 10, 12, 13, and 14, which this study is helping to fill. At the same time, these underexplained decisions are influenced by 14 of the 44 (32%) incoming arrows in Fig. 2 and influence the other decisions in 6 of the 44 (14%) instances. These interrelations among decisions to be considered when crafting an SLR were scattered across prior guidelines, lacked in-depth elaborations, and were hardly explicitly related to each other. Thus, we hope that our study and the refined SLR process model will help enhance the quality and contribution of future SLRs.

Data availablity

The data generated during this research is summarized in Table 3 and the analyzed papers are publicly available. They are clearly identified in Table 3 and the reference list.

Aguinis H, Ramani RS, Alabduljader N (2020) Best-practice recommendations for producers, evaluators, and users of methodological literature reviews. Organ Res Methods. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428120943281

Article Google Scholar

Beske P, Land A, Seuring S (2014) Sustainable supply chain management practices and dynamic capabilities in the food industry: a critical analysis of the literature. Int J Prod Econ 152:131–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2013.12.026

Brandenburg M, Rebs T (2015) Sustainable supply chain management: a modeling perspective. Ann Oper Res 229:213–252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-015-1853-1

Carter CR, Rogers DS (2008) A framework of sustainable supply chain management: moving toward new theory. Int Jnl Phys Dist Logist Manage 38:360–387. https://doi.org/10.1108/09600030810882816

Carter CR, Washispack S (2018) Mapping the path forward for sustainable supply chain management: a review of reviews. J Bus Logist 39:242–247. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbl.12196

Clark WR, Clark LA, Raffo DM, Williams RI (2021) Extending fisch and block’s (2018) tips for a systematic review in management and business literature. Manag Rev Q 71:215–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-020-00184-8

Crane A, Henriques I, Husted BW, Matten D (2016) What constitutes a theoretical contribution in the business and society field? Bus Soc 55:783–791. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650316651343

Davis J, Mengersen K, Bennett S, Mazerolle L (2014) Viewing systematic reviews and meta-analysis in social research through different lenses. Springerplus 3:511. https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-1801-3-511

Davis HTO, Crombie IK (2001) What is asystematicreview? http://vivrolfe.com/ProfDoc/Assets/Davis%20What%20is%20a%20systematic%20review.pdf . Accessed 22 February 2019

De Lima FA, Seuring S, Sauer PC (2021) A systematic literature review exploring uncertainty management and sustainability outcomes in circular supply chains. Int J Prod Res. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2021.1976859

Denyer D, Tranfield D (2009) Producing a systematic review. In: Buchanan DA, Bryman A (eds) The Sage handbook of organizational research methods. Sage Publications Ltd, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp 671–689

Google Scholar

Devece C, Ribeiro-Soriano DE, Palacios-Marqués D (2019) Coopetition as the new trend in inter-firm alliances: literature review and research patterns. Rev Manag Sci 13:207–226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-017-0245-0

Dieste M, Sauer PC, Orzes G (2022) Organizational tensions in industry 4.0 implementation: a paradox theory approach. Int J Prod Econ 251:108532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2022.108532

Donthu N, Kumar S, Mukherjee D, Pandey N, Lim WM (2021) How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: an overview and guidelines. J Bus Res 133:285–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.070

Durach CF, Kembro J, Wieland A (2017) A new paradigm for systematic literature reviews in supply chain management. J Supply Chain Manag 53:67–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/jscm.12145

Fink A (2010) Conducting research literature reviews: from the internet to paper, 3rd edn. SAGE, Los Angeles

Fisch C, Block J (2018) Six tips for your (systematic) literature review in business and management research. Manag Rev Q 68:103–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-018-0142-x

Fritz MMC, Silva ME (2018) Exploring supply chain sustainability research in Latin America. Int Jnl Phys Dist Logist Manag 48:818–841. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-01-2017-0023

Garcia-Torres S, Albareda L, Rey-Garcia M, Seuring S (2019) Traceability for sustainability: literature review and conceptual framework. Supp Chain Manag 24:85–106. https://doi.org/10.1108/SCM-04-2018-0152

Hanelt A, Bohnsack R, Marz D, Antunes Marante C (2021) A systematic review of the literature on digital transformation: insights and implications for strategy and organizational change. J Manag Stud 58:1159–1197. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12639

Kache F, Seuring S (2014) Linking collaboration and integration to risk and performance in supply chains via a review of literature reviews. Supp Chain Mnagmnt 19:664–682. https://doi.org/10.1108/SCM-12-2013-0478

Khalid RU, Seuring S (2019) Analyzing base-of-the-pyramid research from a (sustainable) supply chain perspective. J Bus Ethics 155:663–686. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3474-x

Koufteros X, Mackelprang A, Hazen B, Huo B (2018) Structured literature reviews on strategic issues in SCM and logistics: part 2. Int Jnl Phys Dist Logist Manage 48:742–744. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-09-2018-363

Kraus S, Breier M, Dasí-Rodríguez S (2020) The art of crafting a systematic literature review in entrepreneurship research. Int Entrep Manag J 16:1023–1042. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-020-00635-4

Kraus S, Mahto RV, Walsh ST (2021) The importance of literature reviews in small business and entrepreneurship research. J Small Bus Manag. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2021.1955128

Kraus S, Breier M, Lim WM, Dabić M, Kumar S, Kanbach D, Mukherjee D, Corvello V, Piñeiro-Chousa J, Liguori E, Palacios-Marqués D, Schiavone F, Ferraris A, Fernandes C, Ferreira JJ (2022) Literature reviews as independent studies: guidelines for academic practice. Rev Manag Sci 16:2577–2595. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-022-00588-8

Leuschner R, Rogers DS, Charvet FF (2013) A meta-analysis of supply chain integration and firm performance. J Supply Chain Manag 49:34–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/jscm.12013

Lim WM, Rasul T (2022) Customer engagement and social media: revisiting the past to inform the future. J Bus Res 148:325–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.04.068

Lim WM, Yap S-F, Makkar M (2021) Home sharing in marketing and tourism at a tipping point: what do we know, how do we know, and where should we be heading? J Bus Res 122:534–566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.08.051

Lim WM, Kumar S, Ali F (2022) Advancing knowledge through literature reviews: ‘what’, ‘why’, and ‘how to contribute.’ Serv Ind J 42:481–513. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2022.2047941

Lusiantoro L, Yates N, Mena C, Varga L (2018) A refined framework of information sharing in perishable product supply chains. Int J Phys Distrib Logist Manag 48:254–283. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-08-2017-0250

Maestrini V, Luzzini D, Maccarrone P, Caniato F (2017) Supply chain performance measurement systems: a systematic review and research agenda. Int J Prod Econ 183:299–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2016.11.005

Miemczyk J, Johnsen TE, Macquet M (2012) Sustainable purchasing and supply management: a structured literature review of definitions and measures at the dyad, chain and network levels. Supp Chain Mnagmnt 17:478–496. https://doi.org/10.1108/13598541211258564