Quick links

- Directories

- Make a Gift

Writing Papers That Apply Sociological Theories or Perspectives

This document is intended as an additional resource for undergraduate students taking sociology courses at UW. It is not intended to replace instructions from your professors and TAs. In all cases follow course-specific assignment instructions, and consult your TA or professor if you have questions.

About These Assignments

Theory application assignments are a common type of analytical writing assigned in sociology classes. Many instructors expect you to apply sociological theories (sometimes called "perspectives" or "arguments") to empirical phenomena. [1] There are different ways to do this, depending upon your objectives, and of course, the specifics of each assignment. You can choose cases that confirm (support), disconfirm (contradict), [2] or partially confirm any theory.

How to Apply Theory to Empirical Phenomena

Theory application assignments generally require you to look at empirical phenomena through the lens of theory. Ask yourself, what would the theory predict ("have to say") about a particular situation. According to the theory, if particular conditions are present or you see a change in a particular variable, what outcome should you expect?

Generally, a first step in a theory application assignment is to make certain you understand the theory! You should be able to state the theory (the author's main argument) in a sentence or two. Usually, this means specifying the causal relationship (X—>Y) or the causal model (which might involve multiple variables and relationships).

For those taking sociological theory classes, in particular, you need to be aware that theories are constituted by more than causal relationships. Depending upon the assignment, you may be asked to specify the following:

- Causal Mechanism: This is a detailed explanation about how X—>Y, often made at a lower level of analysis (i.e., using smaller units) than the causal relationship.

- Level of Analysis: Macro-level theories refer to society- or group-level causes and processes; micro-level theories address individual-level causes and processes.

- Scope Conditions: These are parameters or boundaries specified by the theorist that identify the types of empirical phenomena to which the theory applies.

- Assumptions: Most theories begin by assuming certain "facts." These often concern the bases of human behavior: for example, people are inherently aggressive or inherently kind, people act out of self-interest or based upon values, etc.

Theories vary in terms of whether they specify assumptions, scope conditions and causal mechanisms. Sometimes they can only be inferred: when this is the case, be clear about that in your paper.

Clearly understanding all the parts of a theory helps you ensure that you are applying the theory correctly to your case. For example, you can ask whether your case fits the theory's assumptions and scope conditions. Most importantly, however, you should single out the main argument or point (usually the causal relationship and mechanism) of the theory. Does the theorist's key argument apply to your case? Students often go astray here by latching onto an inconsequential or less important part of the theory reading, showing the relationship to their case, and then assuming they have fully applied the theory.

Using Evidence to Make Your Argument

Theory application papers involve making a claim or argument based on theory, supported by empirical evidence. [3] There are a few common problems that students encounter while writing these types of assignments: unsubstantiated claims/generalizations; "voice" issues or lack of attribution; excessive summarization/insufficient analysis. Each class of problem is addressed below, followed by some pointers for choosing "cases," or deciding upon the empirical phenomenon to which you will apply the theoretical perspective or argument (including where to find data).

A common problem seen in theory application assignments is failing to substantiate claims, or making a statement that is not backed up with evidence or details ("proof"). When you make a statement or a claim, ask yourself, "How do I know this?" What evidence can you marshal to support your claim? Put this evidence in your paper (and remember to cite your sources). Similarly, be careful about making overly strong or broad claims based on insufficient evidence. For example, you probably don't want to make a claim about how Americans feel about having a black president based on a poll of UW undergraduates. You may also want to be careful about making authoritative (conclusive) claims about broad social phenomena based on a single case study.

In addition to un- or under-substantiated claims, another problem that students often encounter when writing these types of papers is lack of clarity regarding "voice," or whose ideas they are presenting. The reader is left wondering whether a given statement represents the view of the theorist, the student, or an author who wrote about the case. Be careful to identify whose views and ideas you are presenting. For example, you could write, "Marx views class conflict as the engine of history;" or, "I argue that American politics can best be understood through the lens of class conflict;" [4] or, "According to Ehrenreich, Walmart employees cannot afford to purchase Walmart goods."

Another common problem that students encounter is the trap of excessive summarization. They spend the majority of their papers simply summarizing (regurgitating the details) of a case—much like a book report. One way to avoid this is to remember that theory indicates which details (or variables) of a case are most relevant, and to focus your discussion on those aspects. A second strategy is to make sure that you relate the details of the case in an analytical fashion. You might do this by stating an assumption of Marxist theory, such as "man's ideas come from his material conditions," and then summarizing evidence from your case on that point. You could organize the details of the case into paragraphs and start each paragraph with an analytical sentence about how the theory relates to different aspects of the case.

Some theory application papers require that you choose your own case (an empirical phenomenon, trend, situation, etc.), whereas others specify the case for you (e.g., ask you to apply conflict theory to explain some aspect of globalization described in an article). Many students find choosing their own case rather challenging. Some questions to guide your choice are:

- Can I obtain sufficient data with relative ease on my case?

- Is my case specific enough? If your subject matter is too broad or abstract, it becomes both difficult to gather data and challenging to apply the theory.

- Is the case an interesting one? Professors often prefer that you avoid examples used by the theorist themselves, those used in lectures and sections, and those that are extremely obvious.

Where You Can Find Data

Data is collected by many organizations (e.g., commercial, governmental, nonprofit, academic) and can frequently be found in books, reports, articles, and online sources. The UW libraries make your job easy: on the front page of the library website ( www.lib.washington.edu ), in the left hand corner you will see a list of options under the heading "Find It" that allows you to go directly to databases, specific online journals, newspapers, etc. For example, if you are choosing a historical case, you might want to access newspaper articles. This has become increasingly easy to do, as many are now online through the UW library. For example, you can search The New York Times and get full-text online for every single issue from 1851 through today! If you are interested in interview or observational data, you might try to find books or articles that are case-studies on your topic of interest by conducting a simple keyword search of the UW library book holdings, or using an electronic database, such as JSTOR or Sociological Abstracts. Scholarly articles are easy to search through, since they contain abstracts, or paragraphs that summarize the topic, relevant literature, data and methods, and major findings. When using JSTOR, you may want to limit your search to sociology (which includes 70 journals) and perhaps political science; this database retrieves full-text articles. Sociological Abstracts will cast a wider net searching many more sociology journals, but the article may or may not be available online (find out by clicking "check for UW holdings"). A final word about using academic articles for data: remember that you need to cite your sources, and follow the instructions of your assignment. This includes making your own argument about your case, not using an argument you find in a scholarly article.

In addition, there are many data sources online. For example, you can get data from the US census, including for particular neighborhoods, from a number of cites. You can get some crime data online: the Seattle Police Department publishes several years' worth of crime rates. There are numerous cites on public opinion, including gallup.com. There is an online encyclopedia on Washington state history, including that of individual Seattle neighborhoods ( www.historylink.org ). These are just a couple options: a simple google search will yield hundreds more. Finally, remember that librarian reference desks are expert on data sources, and that you can call, email, or visit in person to ask about what data is available on your particular topic. You can chat with a librarian 24 hours a day online, as well (see the "Ask Us!" link on the front page of UW libraries website for contact information).

[1] By empirical phenomena, we mean some sort of observed, real-world conditions. These include societal trends, events, or outcomes. They are sometimes referred to as "cases." Return to Reading

[2] A cautionary note about critiquing theories: no social theory explains all cases, so avoid claiming that a single case "disproves" a theory, or that a single case "proves" a theory correct. Moreover, if you choose a case that disconfirms a theory, you should be careful that the case falls within the scope conditions (see above) of the given theory. For example, if a theorist specifies that her argument pertains to economic transactions, it would not be a fair critique to say the theory doesn't explain dynamics within a family. On the other hand, it is useful and interesting to apply theories to cases not foreseen by the original theorist (we see this in sociological theories that incorporate theories from evolutionary biology or economics). Return to Reading

[3] By empirical evidence, we mean data on social phenomena, derived from scientific observation or experiment. Empirical evidence may be quantitative (e.g., statistical data) or qualitative (e.g., descriptions derived from systematic observation or interviewing), or a mixture of both. Empirical evidence must be observable and derived from real-world conditions (present or historical) rather than hypothetical or "imagined". For additional help, see the "Where You Can Find Data" section on the next page. Return to Reading

[4] If your instructor does not want you to use the first-person, you could write, "This paper argues…" Return to Reading

- Newsletter

1.3 Theoretical Perspectives in Sociology

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section you should be able to:

- Describe the ways that sociological theories are used to explain social institutions.

- Differentiate between functionalism, conflict theory, and symbolic interactionism.

Sociologists study social events, interactions, and patterns, and they develop theories to explain why things work as they do. In sociology, a theory is a way to explain different aspects of social interactions and to create a testable proposition, called a hypothesis , about society (Allan 2006).

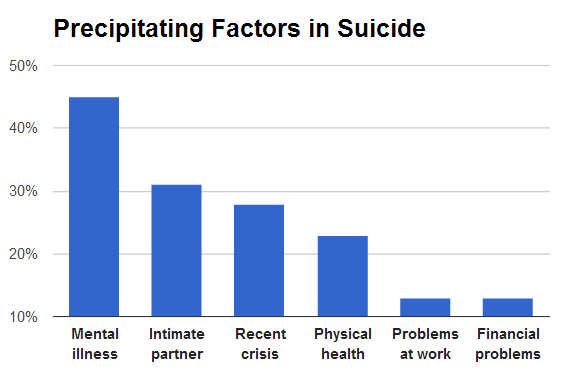

For example, although suicide is generally considered an individual phenomenon, Émile Durkheim was interested in studying the social factors that affect it. He studied social solidarity , social ties within a group, and hypothesized that differences in suicide rates might be explained by religious differences. Durkheim gathered a large amount of data about Europeans and found that Protestants were more likely to commit suicide than Catholics. His work supports the utility of theory in sociological research.

Theories vary in scope depending on the scale of the issues that they are meant to explain. Macro-level theories relate to large-scale issues and large groups of people, while micro-level theories look at very specific relationships between individuals or small groups. Grand theories attempt to explain large-scale relationships and answer fundamental questions such as why societies form and why they change. Sociological theory is constantly evolving and should never be considered complete. Classic sociological theories are still considered important and current, but new sociological theories build upon the work of their predecessors and add to them (Calhoun, 2002).

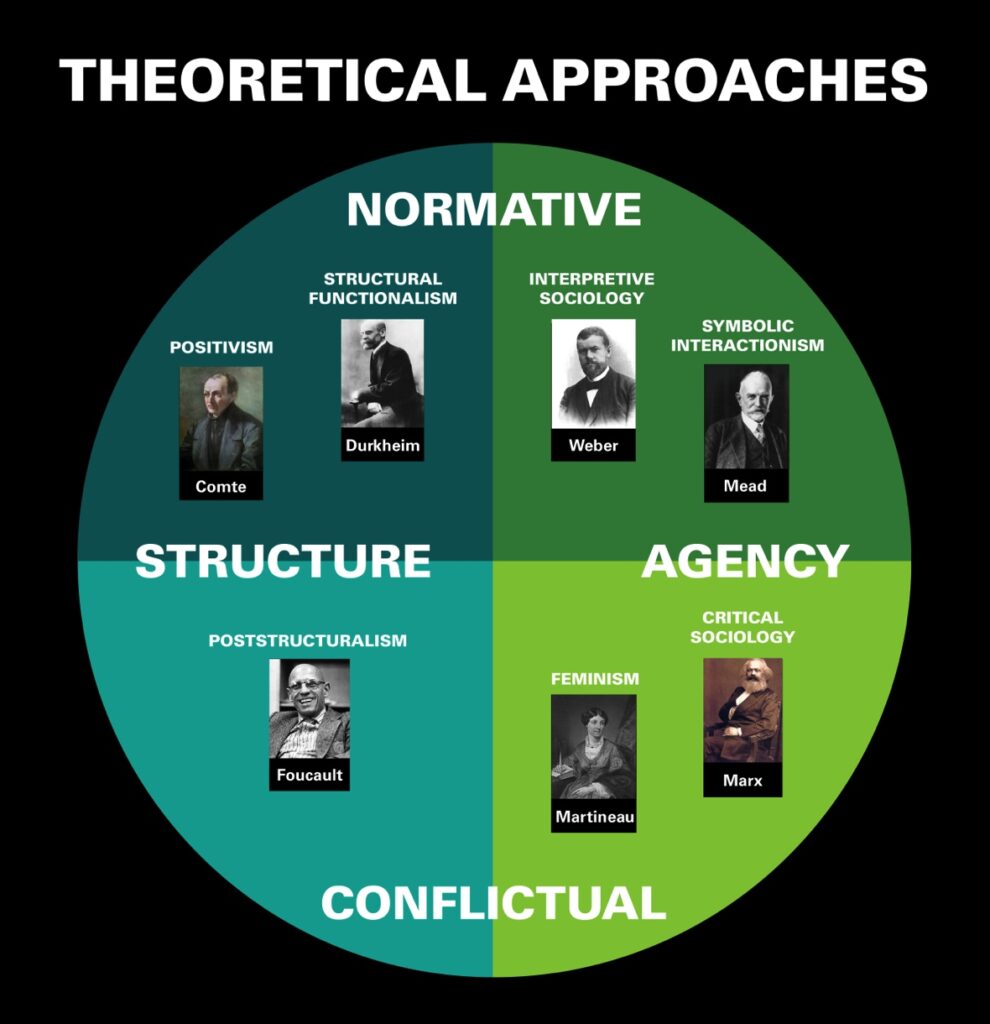

In sociology, a few theories provide broad perspectives that help explain many different aspects of social life, and these are called paradigms . Paradigms are philosophical and theoretical frameworks used within a discipline to formulate theories, generalizations, and the experiments performed in support of them. Three paradigms have come to dominate sociological thinking because they provide useful explanations: structural functionalism, conflict theory, and symbolic interactionism.

| Sociological Theories/Paradigms | Level of Analysis | Focus | Analogies | Questions that might be asked |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Functionalism | Macro or Mid | The way each part of society functions together to contribute to the functioning of the whole. | How each organ works to keep your body healthy (or not.) | How does education work to transmit culture? |

| Conflict Theory | Macro | The way inequities and inequalities contribute to social, political, and power differences and how they perpetuate power. | The ones with the most toys wins and they will change the rules to the games to keep winning. | Does education transmit only the values of the most dominant groups? |

| Symbolic Interactionism | Micro | The way one-on-one interactions and communications behave. | What’s it mean to be an X? | How do students react to cultural messages in school? |

Functionalism

Functionalism , also called structural-functional theory, sees society as a structure with interrelated parts designed to meet the biological and social needs of the individuals in that society. Functionalism grew out of the writings of English philosopher and biologist, Herbert Spencer, who saw similarities between society and the human body. He argued that just as the various organs of the body work together to keep the body functioning, the various parts of society work together to keep society functioning (Spencer, 1898). The parts of society that Spencer referred to were the social institutions , or patterns of beliefs and behaviors focused on meeting social needs, such as government, education, family, healthcare, religion, and the economy.

Émile Durkheim applied Spencer’s theory to explain how societies change and survive over time. Durkheim believed that society is a complex system of interrelated and interdependent parts that work together to maintain stability (Durkheim, 1893), and that society is held together by shared values, languages, and symbols. He believed that to study society, a sociologist must look beyond individuals to social facts such as laws, morals, values, religious beliefs, customs, fashion, and rituals, which all serve to govern social life (Durkheim, 1895). Alfred Radcliffe-Brown (1881–1955), a social anthropologist, defined the function of any recurrent activity as the part it played in social life as a whole, and therefore the contribution it makes to social stability and continuity (Radcliffe-Brown 1952). In a healthy society, all parts work together to maintain stability, a state called dynamic equilibrium by later sociologists such as Parsons (1961).

Durkheim believed that individuals may make up society, but in order to study society, sociologists have to look beyond individuals to social facts. . Each of these social facts serves one or more functions within a society. For example, one function of a society’s laws may be to protect society from violence, while another is to punish criminal behavior, while another is to preserve public health.

Another noted structural functionalist, Robert Merton (1910–2003), pointed out that social processes often have many functions. Manifest functions are the consequences of a social process that are sought or anticipated, while latent functions are the unsought consequences of a social process. A manifest function of a college education, for example, includes gaining knowledge, preparing for a career, and finding a good job that utilizes that education. Latent functions of your college years include meeting new people, participating in extracurricular activities, or even finding a spouse or partner. Another latent function of education is creating a hierarchy of employment based on the level of education attained. Latent functions can be beneficial, neutral, or harmful. Social processes that have undesirable consequences for the operation of society are called dysfunctions . In education, examples of dysfunction include getting bad grades, truancy, dropping out, not graduating, and not finding suitable employment.

One criticism of the structural-functional theory is that it can’t adequately explain social change even though the functions are processes. Also problematic is the somewhat circular nature of this theory: repetitive behavior patterns are assumed to have a function, yet we profess to know that they have a function only because they are repeated. Furthermore, dysfunctions may continue, even though they don’t serve a function, which seemingly contradicts the basic premise of the theory. Many sociologists now believe that functionalism is no longer useful as a macro-level theory, but that it does serve a useful purpose in some mid-level analyses.

Big Picture

A global culture.

Sociologists around the world look closely for signs of what would be an unprecedented event: the emergence of a global culture. In the past, empires such as those that existed in China, Europe, Africa, and Central and South America linked people from many different countries, but those people rarely became part of a common culture. They lived too far from each other, spoke different languages, practiced different religions, and traded few goods. Today, increases in communication, travel, and trade have made the world a much smaller place. More and more people are able to communicate with each other instantly—wherever they are located—by telephone, video, and text. They share movies, television shows, music, games, and information over the Internet. Students can study with teachers and pupils from the other side of the globe. Governments find it harder to hide conditions inside their countries from the rest of the world.

Sociologists research many different aspects of this potential global culture. Some explore the dynamics involved in the social interactions of global online communities, such as when members feel a closer kinship to other group members than to people residing in their own countries. Other sociologists study the impact this growing international culture has on smaller, less-powerful local cultures. Yet other researchers explore how international markets and the outsourcing of labor impact social inequalities. Sociology can play a key role in people’s abilities to understand the nature of this emerging global culture and how to respond to it.

Conflict Theory

Conflict theory looks at society as a competition for limited resources. This perspective is a macro-level approach most identified with the writings of German philosopher and economist Karl Marx, who saw society as being made up of individuals in different social classes who must compete for social, material, and political resources such as food and housing, employment, education, and leisure time. Social institutions like government, education, and religion reflect this competition in their inherent inequalities and help maintain the unequal social structure. Some individuals and organizations are able to obtain and keep more resources than others, and these “winners” use their power and influence to maintain social institutions. The perpetuation of power results in the perpetuation of oppression.

Several theorists suggested variations on this basic theme like Polish-Austrian sociologist Ludwig Gumplowicz (1838–1909) who expanded on Marx’s ideas by arguing that war and conquest are the bases of civilizations. He believed that cultural and ethnic conflicts led to states being identified and defined by a dominant group that had power over other groups (Irving, 2007).

German sociologist Max Weber (1864–1920) agreed with Marx but also believed that, in addition to economic inequalities, inequalities of political power and social structure cause conflict. Weber noted that different groups were affected differently based on education, race, and gender, and that people’s reactions to inequality were moderated by class differences and rates of social mobility, as well as by perceptions about the legitimacy of those in power. A reader of Marx, Georg Simmel believed that conflict can help integrate and stabilize a society. He said that the intensity of the conflict varies depending on the emotional involvement of the parties, the degree of solidarity within the opposing groups, and the clarity and limited nature of the goals. Simmel also showed that groups work to create internal solidarity, centralize power, and reduce dissent. The stronger the bond, the weaker the discord. Resolving conflicts can reduce tension and hostility and can pave the way for future agreements.

In the 1930s and 1940s, German philosophers, known as the Frankfurt School, developed critical theory as an elaboration on Marxist principles. Critical theory is an expansion of conflict theory and is broader than just sociology, incorporating other social sciences and philosophy. A critical theory is a holistic theory and attempts to address structural issues causing inequality. It must explain what’s wrong in current social reality, identify the people who can make changes, and provide practical goals for social transformation (Horkeimer, 1982).

More recently, inequality based on gender or race has been explained in a similar manner and has identified institutionalized power structures that help to maintain inequality between groups. Janet Saltzman Chafetz (1941–2006) presented a model of feminist theory that attempts to explain the forces that maintain gender inequality as well as a theory of how such a system can be changed (Turner, 2003). Similarly, critical race theory grew out of a critical analysis of race and racism from a legal point of view. Critical race theory looks at structural inequality based on white privilege and associated wealth, power, and prestige.

Sociology in the Real World

Farming and locavores: how sociological perspectives might view food consumption.

The consumption of food is a commonplace, daily occurrence. Yet, it can also be associated with important moments in our lives. Eating can be an individual or a group action, and eating habits and customs are influenced by our cultures. In the context of society, our nation’s food system is at the core of numerous social movements, political issues, and economic debates. Any of these factors might become a topic of sociological study.

A structural-functional approach to the topic of food consumption might analyze the role of the agriculture industry within the nation’s economy and how this has changed from the early days of manual-labor farming to modern mechanized production. Another might study the different functions of processes in food production, from farming and harvesting to flashy packaging and mass consumerism.

A conflict theorist might be interested in the power differentials present in the regulation of food, by exploring where people’s right to information intersects with corporations’ drive for profit and how the government mediates those interests. Or a conflict theorist might examine the power and powerlessness experienced by local farmers versus large farming conglomerates, such as the documentary Food Inc., which depicts as resulting from Monsanto’s patenting of seed technology. Another topic of study might be how nutrition varies between different social classes.

A sociologist viewing food consumption through a symbolic interactionist lens would be more interested in microlevel topics, such as the symbolic use of food in religious rituals, or the role it plays in the social interaction of a family dinner. This perspective might also explore the interactions among group members who identify themselves based on their sharing a particular diet, such as vegetarians (people who don’t eat meat) or locavores (people who strive to eat locally produced food).

Just as structural functionalism was criticized for focusing too much on the stability of societies, conflict theory has been criticized because it tends to focus on conflict to the exclusion of recognizing stability. Many social structures are extremely stable or have gradually progressed over time rather than changing abruptly as conflict theory would suggest.

Symbolic Interactionist Theory

Symbolic interactionism is a micro-level theory that focuses on the relationships among individuals within a society. Communication—the exchange of meaning through language and symbols—is believed to be the way in which people make sense of their social worlds. Theorists Herman and Reynolds (1994) note that this perspective sees people as being active in shaping the social world rather than simply being acted upon.

George Herbert Mead is considered a founder of symbolic interactionism though he never published his work on it (LaRossa and Reitzes, 1993). Mead’s student, Herbert Blumer (1900-1987), coined the term “symbolic interactionism” and outlined these basic premises: humans interact with things based on meanings ascribed to those things; the ascribed meaning of things comes from our interactions with others and society; the meanings of things are interpreted by a person when dealing with things in specific circumstances (Blumer 1969). If you love books, for example, a symbolic interactionist might propose that you learned that books are good or important in the interactions you had with family, friends, school, or church. Maybe your family had a special reading time each week, getting your library card was treated as a special event, or bedtime stories were associated with warmth and comfort.

Social scientists who apply symbolic-interactionist thinking look for patterns of interaction between individuals. Their studies often involve observation of one-on-one interactions. For example, while a conflict theorist studying a political protest might focus on class difference, a symbolic interactionist would be more interested in how individuals in the protesting group interact, as well as the signs and symbols protesters use to communicate their message.

The focus on the importance of symbols in building a society led sociologists like Erving Goffman (1922-1982) to develop a technique called dramaturgical analysis . Goffman used theater as an analogy for social interaction and recognized that people’s interactions showed patterns of cultural “scripts.” He argued that individuals were actors in a play. We switched roles, sometimes minute to minute—for example, from student or daughter to dog walker. Because it can be unclear what part a person may play in a given situation, he or she has to improvise his or her role as the situation unfolds (Goffman, 1958).

Studies that use the symbolic interactionist perspective are more likely to use qualitative research methods, such as in-depth interviews or participant observation, because they seek to understand the symbolic worlds in which research subjects live.

Constructivism is an extension of symbolic interaction theory which proposes that reality is what humans cognitively construct it to be. We develop social constructs based on interactions with others, and those constructs that last over time are those that have meanings which are widely agreed-upon or generally accepted by most within the society. This approach is often used to examine what’s defined as deviant within a society. There is no absolute definition of deviance, and different societies have constructed different meanings for deviance, as well as associating different behaviors with deviance.

One situation that illustrates this is what you believe you’re to do if you find a wallet in the street. In the United States, turning the wallet in to local authorities would be considered the appropriate action, and to keep the wallet would be seen as deviant. In contrast, many Eastern societies would consider it much more appropriate to keep the wallet and search for the owner yourself. Turning it over to someone else, even the authorities, would be considered deviant behavior.

Research done from this perspective is often scrutinized because of the difficulty of remaining objective. Others criticize the extremely narrow focus on symbolic interaction. Proponents, of course, consider this one of its greatest strengths.

Sociological Theory Today

These three approaches still provide the main foundation of modern sociological theory though they have evolved. Structural-functionalism was a dominant force after World War II and until the 1960s and 1970s. At that time, sociologists began to feel that structural-functionalism did not sufficiently explain the rapid social changes happening in the United States at that time. The women’s movement and the Civil Rights movement forced academics to develop approaches to study these emerging social practices.

Conflict theory then gained prominence, with its emphasis on institutionalized social inequality. Critical theory, and the particular aspects of feminist theory and critical race theory, focused on creating social change through the application of sociological principles. The field saw a renewed emphasis on helping ordinary people understand sociology principles, in the form of public sociology.

Gaining prominence in the wake of Mead’s work in the 1920s and 1930s, symbolic interactionism declined in influence during the 1960s and 1970s only to be revitalized at the turn of the twenty-first century (Stryker, 1987). Postmodern social theory developed in the 1980s to look at society through an entirely new lens by rejecting previous macro-level attempts to explain social phenomena. Its growth in popularity coincides with the rise of constructivist views of symbolic interactionism.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Introduction to Sociology 3e

- Publication date: Jun 3, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-3-theoretical-perspectives-in-sociology

© Aug 5, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

What this handout is about

This handout introduces you to the wonderful world of writing sociology. Before you can write a clear and coherent sociology paper, you need a firm understanding of the assumptions and expectations of the discipline. You need to know your audience, the way they view the world and how they order and evaluate information. So, without further ado, let’s figure out just what sociology is, and how one goes about writing it.

What is sociology, and what do sociologists write about?

Unlike many of the other subjects here at UNC, such as history or English, sociology is a new subject for many students. Therefore, it may be helpful to give a quick introduction to what sociologists do. Sociologists are interested in all sorts of topics. For example, some sociologists focus on the family, addressing issues such as marriage, divorce, child-rearing, and domestic abuse, the ways these things are defined in different cultures and times, and their effect on both individuals and institutions. Others examine larger social organizations such as businesses and governments, looking at their structure and hierarchies. Still others focus on social movements and political protest, such as the American civil rights movement. Finally, sociologists may look at divisions and inequality within society, examining phenomena such as race, gender, and class, and their effect on people’s choices and opportunities. As you can see, sociologists study just about everything. Thus, it is not the subject matter that makes a paper sociological, but rather the perspective used in writing it.

So, just what is a sociological perspective? At its most basic, sociology is an attempt to understand and explain the way that individuals and groups interact within a society. How exactly does one approach this goal? C. Wright Mills, in his book The Sociological Imagination (1959), writes that “neither the life of an individual nor the history of a society can be understood without understanding both.” Why? Well, as Karl Marx observes at the beginning of The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (1852), humans “make their own history, but they do not make it just as they please; they do not make it under circumstances chosen by themselves, but under circumstances directly encountered, given and transmitted from the past.” Thus, a good sociological argument needs to balance both individual agency and structural constraints. That is certainly a tall order, but it is the basis of all effective sociological writing. Keep it in mind as you think about your own writing.

Key assumptions and characteristics of sociological writing

What are the most important things to keep in mind as you write in sociology? Pay special attention to the following issues.

The first thing to remember in writing a sociological argument is to be as clear as possible in stating your thesis. Of course, that is true in all papers, but there are a couple of pitfalls common to sociology that you should be aware of and avoid at all cost. As previously defined, sociology is the study of the interaction between individuals and larger social forces. Different traditions within sociology tend to favor one side of the equation over the other, with some focusing on the agency of individual actors and others on structural factors. The danger is that you may go too far in either of these directions and thus lose the complexity of sociological thinking. Although this mistake can manifest itself in any number of ways, three types of flawed arguments are particularly common:

- The “ individual argument ” generally takes this form: “The individual is free to make choices, and any outcomes can be explained exclusively through the study of their ideas and decisions.” While it is of course true that we all make our own choices, we must also keep in mind that, to paraphrase Marx, we make these choices under circumstances given to us by the structures of society. Therefore, it is important to investigate what conditions made these choices possible in the first place, as well as what allows some individuals to successfully act on their choices while others cannot.

- The “ human nature argument ” seeks to explain social behavior through a quasi-biological argument about humans, and often takes a form such as: “Humans are by nature X, therefore it is not surprising that Y.” While sociologists disagree over whether a universal human nature even exists, they all agree that it is not an acceptable basis of explanation. Instead, sociology demands that you question why we call some behavior natural, and to look into the social factors which have constructed this “natural” state.

- The “ society argument ” often arises in response to critiques of the above styles of argumentation, and tends to appear in a form such as: “Society made me do it.” Students often think that this is a good sociological argument, since it uses society as the basis for explanation. However, the problem is that the use of the broad concept “society” masks the real workings of the situation, making it next to impossible to build a strong case. This is an example of reification, which is when we turn processes into things. Society is really a process, made up of ongoing interactions at multiple levels of size and complexity, and to turn it into a monolithic thing is to lose all that complexity. People make decisions and choices. Some groups and individuals benefit, while others do not. Identifying these intermediate levels is the basis of sociological analysis.

Although each of these three arguments seems quite different, they all share one common feature: they assume exactly what they need to be explaining. They are excellent starting points, but lousy conclusions.

Once you have developed a working argument, you will next need to find evidence to support your claim. What counts as evidence in a sociology paper? First and foremost, sociology is an empirical discipline. Empiricism in sociology means basing your conclusions on evidence that is documented and collected with as much rigor as possible. This evidence usually draws upon observed patterns and information from collected cases and experiences, not just from isolated, anecdotal reports. Just because your second cousin was able to climb the ladder from poverty to the executive boardroom does not prove that the American class system is open. You will need more systematic evidence to make your claim convincing. Above all else, remember that your opinion alone is not sufficient support for a sociological argument. Even if you are making a theoretical argument, you must be able to point to documented instances of social phenomena that fit your argument. Logic is necessary for making the argument, but is not sufficient support by itself.

Sociological evidence falls into two main groups:

- Quantitative data are based on surveys, censuses, and statistics. These provide large numbers of data points, which is particularly useful for studying large-scale social processes, such as income inequality, population changes, changes in social attitudes, etc.

- Qualitative data, on the other hand, comes from participant observation, in-depth interviews, data and texts, as well as from the researcher’s own impressions and reactions. Qualitative research gives insight into the way people actively construct and find meaning in their world.

Quantitative data produces a measurement of subjects’ characteristics and behavior, while qualitative research generates information on their meanings and practices. Thus, the methods you choose will reflect the type of evidence most appropriate to the questions you ask. If you wanted to look at the importance of race in an organization, a quantitative study might use information on the percentage of different races in the organization, what positions they hold, as well as survey results on people’s attitudes on race. This would measure the distribution of race and racial beliefs in the organization. A qualitative study would go about this differently, perhaps hanging around the office studying people’s interactions, or doing in-depth interviews with some of the subjects. The qualitative researcher would see how people act out their beliefs, and how these beliefs interact with the beliefs of others as well as the constraints of the organization.

Some sociologists favor qualitative over quantitative data, or vice versa, and it is perfectly reasonable to rely on only one method in your own work. However, since each method has its own strengths and weaknesses, combining methods can be a particularly effective way to bolster your argument. But these distinctions are not just important if you have to collect your own data for your paper. You also need to be aware of them even when you are relying on secondary sources for your research. In order to critically evaluate the research and data you are reading, you should have a good understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of the different methods.

Units of analysis

Given that social life is so complex, you need to have a point of entry into studying this world. In sociological jargon, you need a unit of analysis. The unit of analysis is exactly that: it is the unit that you have chosen to analyze in your study. Again, this is only a question of emphasis and focus, and not of precedence and importance. You will find a variety of units of analysis in sociological writing, ranging from the individual up to groups or organizations. You should choose yours based on the interests and theoretical assumptions driving your research. The unit of analysis will determine much of what will qualify as relevant evidence in your work. Thus you must not only clearly identify that unit, but also consistently use it throughout your paper.

Let’s look at an example to see just how changing the units of analysis will change the face of research. What if you wanted to study globalization? That’s a big topic, so you will need to focus your attention. Where would you start?

You might focus on individual human actors, studying the way that people are affected by the globalizing world. This approach could possibly include a study of Asian sweatshop workers’ experiences, or perhaps how consumers’ decisions shape the overall system.

Or you might choose to focus on social structures or organizations. This approach might involve looking at the decisions being made at the national or international level, such as the free-trade agreements that change the relationships between governments and corporations. Or you might look into the organizational structures of corporations and measure how they are changing under globalization. Another structural approach would be to focus on the social networks linking subjects together. That could lead you to look at how migrants rely on social contacts to make their way to other countries, as well as to help them find work upon their arrival.

Finally, you might want to focus on cultural objects or social artifacts as your unit of analysis. One fine example would be to look at the production of those tennis shoes the kids seem to like so much. You could look at either the material production of the shoe (tracing it from its sweatshop origins to its arrival on the showroom floor of malls across America) or its cultural production (attempting to understand how advertising and celebrities have turned such shoes into necessities and cultural icons).

Whichever unit of analysis you choose, be careful not to commit the dreaded ecological fallacy. An ecological fallacy is when you assume that something that you learned about the group level of analysis also applies to the individuals that make up that group. So, to continue the globalization example, if you were to compare its effects on the poorest 20% and the richest 20% of countries, you would need to be careful not to apply your results to the poorest and richest individuals.

These are just general examples of how sociological study of a single topic can vary. Because you can approach a subject from several different perspectives, it is important to decide early how you plan to focus your analysis and then stick with that perspective throughout your paper. Avoid mixing units of analysis without strong justification. Different units of analysis generally demand different kinds of evidence for building your argument. You can reconcile the varying levels of analysis, but doing so may require a complex, sophisticated theory, no small feat within the confines of a short paper. Check with your instructor if you are concerned about this happening in your paper.

Typical writing assignments in sociology

So how does all of this apply to an actual writing assignment? Undergraduate writing assignments in sociology may take a number of forms, but they typically involve reviewing sociological literature on a subject; applying or testing a particular concept, theory, or perspective; or producing a small-scale research report, which usually involves a synthesis of both the literature review and application.

The critical review

The review involves investigating the research that has been done on a particular topic and then summarizing and evaluating what you have found. The important task in this kind of assignment is to organize your material clearly and synthesize it for your reader. A good review does not just summarize the literature, but looks for patterns and connections in the literature and discusses the strengths and weaknesses of what others have written on your topic. You want to help your reader see how the information you have gathered fits together, what information can be most trusted (and why), what implications you can derive from it, and what further research may need to be done to fill in gaps. Doing so requires considerable thought and organization on your part, as well as thinking of yourself as an expert on the topic. You need to assume that, even though you are new to the material, you can judge the merits of the arguments you have read and offer an informed opinion of which evidence is strongest and why.

Application or testing of a theory or concept

The application assignment asks you to apply a concept or theoretical perspective to a specific example. In other words, it tests your practical understanding of theories and ideas by asking you to explain how well they apply to actual social phenomena. In order to successfully apply a theory to a new case, you must include the following steps:

- First you need to have a very clear understanding of the theory itself: not only what the theorist argues, but also why they argue that point, and how they justify it. That is, you have to understand how the world works according to this theory and how one thing leads to another.

- Next you should choose an appropriate case study. This is a crucial step, one that can make or break your paper. If you choose a case that is too similar to the one used in constructing the theory in the first place, then your paper will be uninteresting as an application, since it will not give you the opportunity to show off your theoretical brilliance. On the other hand, do not choose a case that is so far out in left field that the applicability is only superficial and trivial. In some ways theory application is like making an analogy. The last thing you want is a weak analogy, or one that is so obvious that it does not give any added insight. Instead, you will want to choose a happy medium, one that is not obvious but that allows you to give a developed analysis of the case using the theory you chose.

- This leads to the last point, which is the analysis. A strong analysis will go beyond the surface and explore the processes at work, both in the theory and in the case you have chosen. Just like making an analogy, you are arguing that these two things (the theory and the example) are similar. Be specific and detailed in telling the reader how they are similar. In the course of looking for similarities, however, you are likely to find points at which the theory does not seem to be a good fit. Do not sweep this discovery under the rug, since the differences can be just as important as the similarities, supplying insight into both the applicability of the theory and the uniqueness of the case you are using.

You may also be asked to test a theory. Whereas the application paper assumes that the theory you are using is true, the testing paper does not makes this assumption, but rather asks you to try out the theory to determine whether it works. Here you need to think about what initial conditions inform the theory and what sort of hypothesis or prediction the theory would make based on those conditions. This is another way of saying that you need to determine which cases the theory could be applied to (see above) and what sort of evidence would be needed to either confirm or disconfirm the theory’s hypothesis. In many ways, this is similar to the application paper, with added emphasis on the veracity of the theory being used.

The research paper

Finally, we reach the mighty research paper. Although the thought of doing a research paper can be intimidating, it is actually little more than the combination of many of the parts of the papers we have already discussed. You will begin with a critical review of the literature and use this review as a basis for forming your research question. The question will often take the form of an application (“These ideas will help us to explain Z.”) or of hypothesis testing (“If these ideas are correct, we should find X when we investigate Y.”). The skills you have already used in writing the other types of papers will help you immensely as you write your research papers.

And so we reach the end of this all-too-brief glimpse into the world of sociological writing. Sociologists can be an idiosyncratic bunch, so paper guidelines and expectations will no doubt vary from class to class, from instructor to instructor. However, these basic guidelines will help you get started.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Cuba, Lee. 2002. A Short Guide to Writing About Social Science , 4th ed. New York: Longman.

Lunsford, Andrea A. 2015. The St. Martin’s Handbook , 8th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Rosen, Leonard J., and Laurence Behrens. 2003. The Allyn & Bacon Handbook , 5th ed. New York: Longman.

Ruszkiewicz, John J., Christy Friend, Daniel Seward, and Maxine Hairston. 2010. The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers , 9th ed. Boston: Pearson Education.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

A Level Sociology Essays – How to Write Them

Table of Contents

Last Updated on November 10, 2022 by

This post offers some advice on how you might plan and write essays in the A level sociology exams.

Essays will either be 20 or 30 marks depending on the paper but the general advice for answering them remains the same:

how to write sociology essays " data-image-caption data-medium-file="https://i0.wp.com/revisesociology.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/peec.jpg?fit=300%2C225&ssl=1" data-large-file="https://i0.wp.com/revisesociology.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/peec.jpg?fit=840%2C630&ssl=1" tabindex=0 role=button width=640 height=480 class="ezlazyload aligncenter wp-image-10399 size-full" src="data:image/svg+xml,%3Csvg%20xmlns=%22http://www.w3.org/2000/svg%22%20width=%22640%22%20height=%22480%22%3E%3C/svg%3E" alt data-recalc-dims=1 ezimgfmt="rs rscb1 src ng ngcb1" data-ezsrc="https://revisesociology.com/ezoimgfmt/i0.wp.com/revisesociology.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/peec.jpg?resize=640%2C480&ssl=1"> how to write sociology essays " data-image-caption data-medium-file="https://i0.wp.com/revisesociology.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/peec.jpg?fit=300%2C225&ssl=1" data-large-file="https://i0.wp.com/revisesociology.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/peec.jpg?fit=840%2C630&ssl=1" tabindex=0 role=button width=640 height=480 class="aligncenter wp-image-10399 size-full" src="https://i0.wp.com/revisesociology.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/peec.jpg?resize=640%2C480&ssl=1" alt data-recalc-dims=1> How to write an A-level sociology essay

Skills in the a level sociology exam, ao1: knowledge and understanding.

You can demonstrate these by:

AO2: Application

Ao3: analysis and evaluation.

NB ‘Assess’ is basically the same as Evaluation

You can demonstrate analysis by….

Use the item

Signposting.

For more exams advice please see my exams and essay advice page

Seven examples of sociology essays, and more advice…

The contents are as follows:.

Introductory Section

These appear first in template form, then with answers, with the skills employed shown in colour. Answers are ‘overkill’ versions designed to get full marks in the exam.

Share this:

One thought on “a level sociology essays – how to write them”, leave a reply cancel reply, discover more from revisesociology.

How to Write a Sociology Essay

Table of Contents

Introduction to Sociology Essay Writing

What is a sociology essay.

A sociology essay is an academic piece that explores various aspects of society and social behavior. It examines patterns, causes, and effects of social interactions among individuals and groups. The purpose of such an essay is to provide a detailed analysis and interpretation of social phenomena, guided by theoretical frameworks and empirical evidence.

Importance of Sociological Inquiry and Critical Thinking

Sociological inquiry is vital as it fosters an understanding of the complexities of society and the various factors that shape human behavior. Critical thinking, on the other hand, is essential in sociology essay writing as it enables the evaluation of arguments, identification of biases, and development of coherent, evidence-based conclusions.

Understanding the Essay Question

Interpreting essay prompts.

To effectively respond to a sociology essay prompt:

- Read Carefully : Look for action words such as ‘discuss,’ ‘compare,’ or ‘analyze’ to understand what is expected.

- Highlight Keywords : Identify key themes, concepts, and sociological terms that are central to the question.

Identifying Key Themes and Concepts

- Break Down the Question : Dissect the question into smaller components to ensure all aspects are addressed.

- Relate to Sociological Theories : Connect the themes with relevant sociological theories and concepts.

Research and Preparation

Conducting sociological research.

- Start Broad : Gain a general understanding of the topic through reputable sources like academic journals and books.

- Narrow Focus : Hone in on specific studies or data that directly relate to your essay’s thesis.

Sourcing and Evaluating Literature

- Use Academic Databases : Access scholarly articles through databases such as JSTOR, Google Scholar, and Sociological Abstracts.

- Evaluate Sources : Check for the credibility, relevance, and timeliness of the literature.

Relevant Sociological Theories

- Theory Identification : Determine which sociological theories and theorists are pertinent to your essay topic.

- Application : Understand how these theories can be applied to the social issue or phenomenon you are examining.

Planning the Essay

Importance of essay structure.

Structuring an essay is crucial because it helps organize thoughts, supports the logical flow of ideas, and guides the reader through the arguments presented. A well-structured essay enhances clarity and readability, ensuring that each point made builds upon the last and contributes to a comprehensive understanding of the topic.

Basic Essay Structure

Introduction : This is where you introduce your topic, provide background information, and present your thesis statement. It sets the stage for your argument.

Thesis Statement : A concise summary of the main point or claim of the essay, usually located at the end of the introduction.

Body Paragraphs : Each paragraph should cover a single point that supports your thesis. Start with a topic sentence, followed by analysis, evidence, and then a concluding sentence that ties the point back to the thesis.

Conclusion : Summarize the key arguments made in the essay and restate the thesis in the context of the evidence presented. Finish with thoughts on the implications, limitations, or suggestions for future research.

Writing the Essay

Crafting a strong thesis statement.

- Specificity : Your thesis should clearly state your position and the aspects of the topic you will explore.

- Scope : Make sure it’s neither too broad nor too narrow to be adequately covered within the essay’s length.

- Assertiveness : Present your thesis confidently and as a statement that you will back up with evidence.

Writing Effective Body Paragraphs

- Topic Sentences : Begin with a clear statement of the paragraph’s main idea.

- Coherence : Use transition words and phrases to maintain flow and show the relationship between paragraphs.

- Evidence Integration : Include data, quotations, or theories from sources that support your argument, always linking them back to your thesis.

Integrating Evidence

- Relevance : Ensure all evidence directly relates to and supports the paragraph’s topic sentence and the overall thesis.

- Credibility : Choose evidence from reputable, scholarly sources.

- Analysis : Don’t just present evidence; interpret it and explain its significance to your argument.

Maintaining Objectivity and Critical Perspective

- Balanced Analysis : Consider multiple viewpoints and avoid biased language.

- Critical Evaluation : Question the methodologies, findings, and biases in the literature you cite.

- Reflective Conclusion : Assess the strengths and limitations of your argument.

Referencing and Citation Style

Importance of citations.

Citations are essential in academic writing as they give credit to the original authors of ideas and information, allow readers to verify sources, and prevent plagiarism.

Common Citation Styles in Sociology

- APA (American Psychological Association) : Commonly used in the social sciences for both in-text citations and reference lists.

- ASA (American Sociological Association) : Specifically designed for sociology papers, this style features a parenthetical author-date format within the text and a detailed reference list at the end.

Each citation style has specific rules for formatting titles, author names, publication dates, and page numbers, so it’s important to consult the relevant style guide to ensure accuracy in your references.

Editing and Proofreading

Strategies for reviewing and refining the essay.

- Take a Break : After writing, step away from your essay before reviewing it. Fresh eyes can catch errors and inconsistencies more effectively.

- Read Aloud : Hearing your words can help identify awkward phrasing, run-on sentences, and other issues that might be missed when reading silently.

- Peer Review : Have a classmate or friend review your essay. They may catch errors you have overlooked and provide valuable feedback.

- Multiple Rounds : Edit for different aspects in each round—for example, content in one, grammar and syntax in another, and citations in the last.

Checklist of Common Errors to Avoid

- Spelling and Grammar : Misused words, typos, subject-verb agreement errors, and incorrect verb tenses.

- Punctuation : Overuse or incorrect use of commas, semicolons, and apostrophes.

- Structure : Lack of clear thesis, poorly structured paragraphs, or missing transitions.

- Clarity : Vague statements, unnecessary jargon, or overly complex sentences.

- Consistency : Fluctuations in tone, style, or tense.

- Citations : Inaccurate references or inconsistent citation style.

Summarizing Arguments

- Restate Thesis : Begin by restating your thesis in a new way, reflecting on the evidence presented.

- Highlight Key Points : Briefly recap the main arguments made in your body paragraphs, synthesizing them to show how they support your thesis.

- No New Information : Ensure that you do not introduce new ideas or evidence in the conclusion.

Presenting Final Thoughts

- Implications : Discuss the broader implications of your findings or argument.

- Limitations : Acknowledge any limitations in your research or analysis and suggest areas for future study.

- Final Statement : End with a strong, closing statement that reinforces the significance of your topic and leaves a lasting impression on the reader.

By carefully editing and proofreading your essay, you can enhance its clarity and coherence, ensuring that it effectively communicates your analysis and insights on the sociological topic. The conclusion serves as the final opportunity to underscore the importance of your findings and to reiterate how they contribute to our understanding of social phenomena.

Appendix A: Example Essay Outlines

An essay outline serves as a roadmap for the writer, indicating the structure of the essay and the sequence of arguments. An appendix containing example outlines could include:

Thematic Essay Outline :

- Background Information

- Thesis Statement

- Summary of Themes

- Restatement of Thesis

- Final Thoughts

Comparative Essay Outline :

- Overview of Subjects Being Compared

- Aspect 1 Comparison

- Evidence from Subject A

- Evidence from Subject B

- Comparative Analysis

- Summary of Comparative Points

These outlines would be followed by brief explanations of each section and tips on what information to include.

Oxford University Press's Academic Insights for the Thinking World

Three top tips for writing sociology essays

The Craft of Writing in Sociology

- By Andrew Balmer and Anne Murcott

- September 19 th 2017

As the academic semester gets underway, we talked to three senior colleagues in Sociology at the University of Manchester to come up with their ‘pet peeves’ when marking student’s essays. Here are some of their comments, and some of our top tips to help you to improve your work.

First, lecturers said they were frustrated with the way that students write their opening paragraphs:

“A main peeve of mine in student writing is poor introductions. Three common errors regularly stand out: throat clearing sentences (e.g. ‘globalisation is an important topic’, ‘Marx was an important writer’); dictionary definitions for core sociological concepts; and introductions that merely restate the question. What I really want to see from an introduction is a brief account of how the student is approaching the question at hand, what key questions the essay will address, and what answer the student will come to at the end of the essay.” – Senior Lecturer in Sociology

This was a point on which our three colleagues agreed: students often waste the introduction. Here is top tip number one to help you improve your essays:

1. Give the reader a guide to your argument. Much as you would give someone directions in how to get to where they’re going, tell your reader what steps you will take, what the key turning points will be, why it is important to take this route and, ultimately, where you will end up. In other words, tell your reader exactly what you will conclude and why, right at the beginning.

Another point on which our colleagues agreed was that sociological essays can be imprecise, and are sometimes written in a style which is meant to sound intellectual, but which is more confusing than it is enlightening. As one senior lecturer put it:

“A pet peeve of mine is imprecise language, for example peppering an essay with terms like ‘however’, ‘therefore’, and ‘consequently’, but without attending to the logical relationship between sentences that those words are supposed to signal. If the logical connector is wrong then the argument fails. This kind of error is often motivated, I think, by students wanting their essays to ‘sound academic’, when often they would have been more convincing by using simpler language more precisely.” – Senior Lecturer in Sociology

It is worth planning the time needed to rework your essays because a good argument can be let down by poor presentation. Here is top tip number two:

2. Your written work should prioritise clarity and concision over entertainment and erudition when making an argument. Students often write in a style which they think makes their points sound important, but get lost in the meaning of what they are saying by doing so. It might be that you have quite a command of English and want to show off your knowledge of polysyllabic or unusual words, or it might be that you wish to imitate the sociological writers whom you admire. Whatever additional reasons you have for writing, there is none more important in a sociological essay than making your argument clear. Words such as ‘however’ and ‘moreover’ should be used to indicate how your ideas are linked together, not to start a sentence with a good word. Be sure that when you edit your work, you edit for the argument, prioritising the word choices which best help to make your point. Such decisions will reflect maturity and consideration in your written work, and it is these which will truly impress a reader.

A final element which our three colleagues all listed in their top pet peeves was poor structure:

“I am often frustrated by the poor structuring of an essay. In other words, with the order in which ideas are presented, either at the level of the whole essay or at paragraph level. Essays that ping-pong from one idea to another, and then back to the original idea, indicate that the student has not really thought their argument through. A trickier thing to get right is the structuring of paragraphs, and some students seem keen to cram in as many (often unconnected) points into one paragraph as possible.” – Senior Lecturer in Sociology

The key point to learn when it comes to structuring your work is to make your writing serve your argument. You should present the main turns of your argument clearly, so as to reach a natural conclusion. Here is top tip number three for improving your essays:

3. Redraft your work for your argument, before you edit and proof-read it. Students often write to tight deadlines and do not plan enough time for a good second draft of their work. Instead, they write a first draft and then edit it as they proof-read it. When writing the first draft of an essay you will still be working out what the argument is. This is because writing helps you to think, so as you write your full first draft you will be meandering around a little, finding the best route as you go. Instead of merely editing this and checking the grammar, you should seriously re-draft the essay in light of the argument you now know you wish to make. This will help you to write a good introduction, since you can now say clearly from the outset what you will go on to argue, and a good conclusion, for you will now be able to say exactly what you have argued and why. Re-drafting for the argument means taking out material, adding in material and ensuring that each paragraph has a main point to contribute. It is an essential step in producing a good essay, which must be undertaken prior to editing for sense and proof-reading for typographical mistakes.

These tips point you towards the most important part of learning to write good sociological essays: bringing everything you do into the service of producing an argument which responds to the question and provides a satisfying answer.

Featured image credit: meeting by Eric Bailey. CC0 Public Domain via Pexels .

Andrew Balmer is Senior Lecturer in Sociology at the University of Manchester and member of the Morgan Centre for Research into Everyday Lives. He is co-author of a new book, The Craft of Writing in Sociology: Developing the Argument in Undergraduate Essays and Dissertations , published by Manchester University Press. Andrew can be found on Twitter @AndyBalmer .

Anne Murcott is Honorary Professor at the University of Nottingham and Honorary Professorial Research Associate at SOAS, University of London. She is author of numerous books and edited collections, including The Craft of Writing in Sociology .

- Arts & Humanities

Our Privacy Policy sets out how Oxford University Press handles your personal information, and your rights to object to your personal information being used for marketing to you or being processed as part of our business activities.

We will only use your personal information to register you for OUPblog articles.

Or subscribe to articles in the subject area by email or RSS

Related posts:

No related posts.

Recent Comments

The recommendations sound more like how to write an abstract than a full essay. If I condense my whole essay into the first paragraph, there is little incentive for a reader to go further. “Formula writing” might simplify paper-marking, but is unlikely to produce truly interesting results. My experience covers 40 years at three major research universities in the U.S.;, and publication in anthropology, linguistics, and education, as well as direction of many doctoral dissertations.

You have explained the topic very well. I want to add something. I am also an educator and I have recently come to know that the week writing skills make students buy essays online.

Even if someone is taking the help in writing, he or she must write their own essays to submit in the class.

[…] and learning responsibilities. On this challenging situation, we, as outdated college students, how to create a good thesis had taken a duty to help a whole new era and supply young people with top quality higher education […]

[…] are many of academic composing how to write an opinion essay duties that the Aussie college students ought to publish and move through in order to rating full […]

[…] the world. Our group cooperates when using most experienced freelance home writers. This can be thesis example for essay a put in place which your projects may be good quality accomplished. Our paperwork will probably be […]

Comments are closed.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1.1 The Sociological Perspective

Learning objectives.

- Define the sociological perspective.

- Provide examples of how Americans may not be as “free” as they think.

- Explain what is meant by considering individuals as “social beings.”

Most Americans probably agree that we enjoy a great amount of freedom. And yet perhaps we have less freedom than we think, because many of our choices are influenced by our society in ways we do not even realize. Perhaps we are not as distinctively individualistic as we believe we are.

For example, consider the right to vote. The secret ballot is one of the most cherished principles of American democracy. We vote in secret so that our choice of a candidate is made freely and without fear of punishment. That is all true, but it is also possible to guess the candidate for whom any one individual will vote if enough is known about the individual. This is because our choice of a candidate is affected by many aspects of our social backgrounds and, in this sense, is not made as freely as we might think.

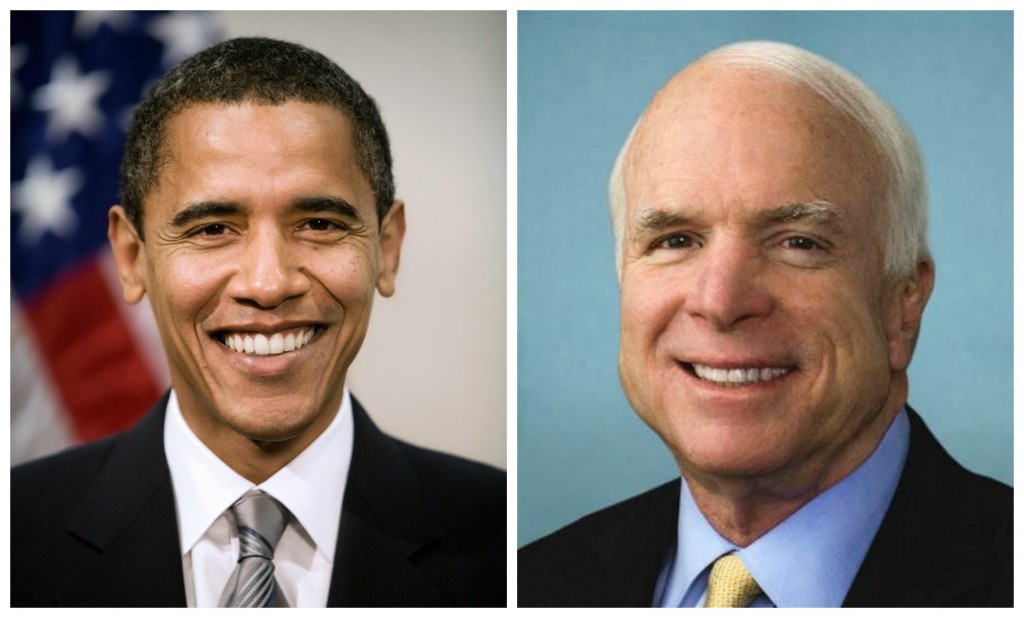

To illustrate this point, consider the 2008 presidential election between Democrat Barack Obama and Republican John McCain. Suppose a room is filled with 100 randomly selected voters from that election. Nothing is known about them except that they were between 18 and 24 years of age when they voted. Because exit poll data found that Obama won 66% of the vote from people in this age group ( http://abcnews.go.com/PollingUnit/ExitPolls ), a prediction that each of these 100 individuals voted for Obama would be correct about 66 times and incorrect only 34 times. Someone betting $1 on each prediction would come out $32 ahead ($66 – $34 = $32), even though the only thing known about the people in the room is their age.

Young people were especially likely to vote for Barack Obama in 2008, while white men tended, especially in Wyoming and several other states, to vote for John McCain. These patterns illustrate the influence of our social backgrounds on many aspects of our lives.

Wikimedia Commons – CC BY 3.0; Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

Now let’s suppose we have a room filled with 100 randomly selected white men from Wyoming who voted in 2008. We know only three things about them: their race, gender, and state of residence. Because exit poll data found that 67% of white men in Wyoming voted for McCain, a prediction can be made with fairly good accuracy that these 100 men tended to have voted for McCain. Someone betting $1 that each man in the room voted for McCain would be right about 67 times and wrong only 33 times and would come out $34 ahead ($67 – $33 = $34). Even though young people in the United States and white men from Wyoming had every right and freedom under our democracy to vote for whomever they wanted in 2008, they still tended to vote for a particular candidate because of the influence of their age (in the case of the young people) or of their gender, race, and state of residence (white men from Wyoming).

Yes, Americans have freedom, but our freedom to think and act is constrained at least to some degree by society’s standards and expectations and by the many aspects of our social backgrounds. This is true for the kinds of important beliefs and behaviors just discussed, and it is also true for less important examples. For instance, think back to the last class you attended. How many of the women wore evening gowns? How many of the men wore skirts? Students are “allowed” to dress any way they want in most colleges and universities, but notice how few students, if any, dress in the way just mentioned. They do not dress that way because of the strange looks and even negative reactions they would receive.

Think back to the last time you rode in an elevator. Why did you not face the back? Why did you not sit on the floor? Why did you not start singing? Children can do these things and “get away with it,” because they look cute doing so, but adults risk looking odd. Because of that, even though we are “allowed” to act strangely in an elevator, we do not.

The basic point is that society shapes our attitudes and behavior even if it does not determine them altogether. We still have freedom, but that freedom is limited by society’s expectations. Moreover, our views and behavior depend to some degree on our social location in society—our gender, race, social class, religion, and so forth. Thus society as a whole and our own social backgrounds affect our attitudes and behaviors. Our social backgrounds also affect one other important part of our lives, and that is our life chances —our chances (whether we have a good chance or little chance) of being healthy, wealthy, and well educated and, more generally, of living a good, happy life.

The influence of our social environment in all of these respects is the fundamental understanding that sociology —the scientific study of social behavior and social institutions—aims to present. At the heart of sociology is the sociological perspective , the view that our social backgrounds influence our attitudes, behavior, and life chances. In this regard, we are not just individuals but rather social beings deeply enmeshed in society. Although we all differ from one another in many respects, we share with many other people basic aspects of our social backgrounds, perhaps especially gender, race and ethnicity, and social class. These shared qualities make us more similar to each other than we would otherwise be.

Does society totally determine our beliefs, behavior, and life chances? No. Individual differences still matter, and disciplines such as psychology are certainly needed for the most complete understanding of human action and beliefs. But if individual differences matter, so do society and the social backgrounds from which we come. Even the most individual attitudes and behaviors, such as the voting decisions discussed earlier, are influenced to some degree by our social backgrounds and, more generally, by the society to which we belong.

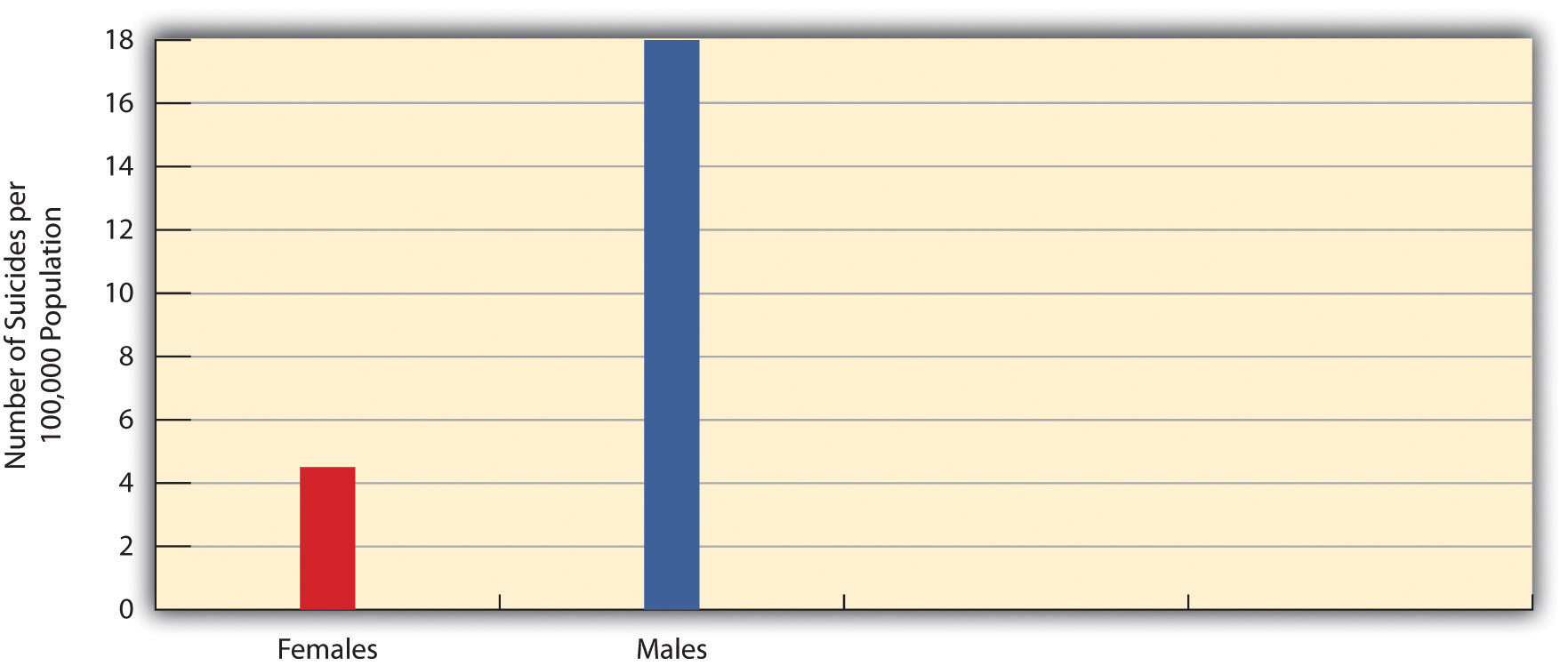

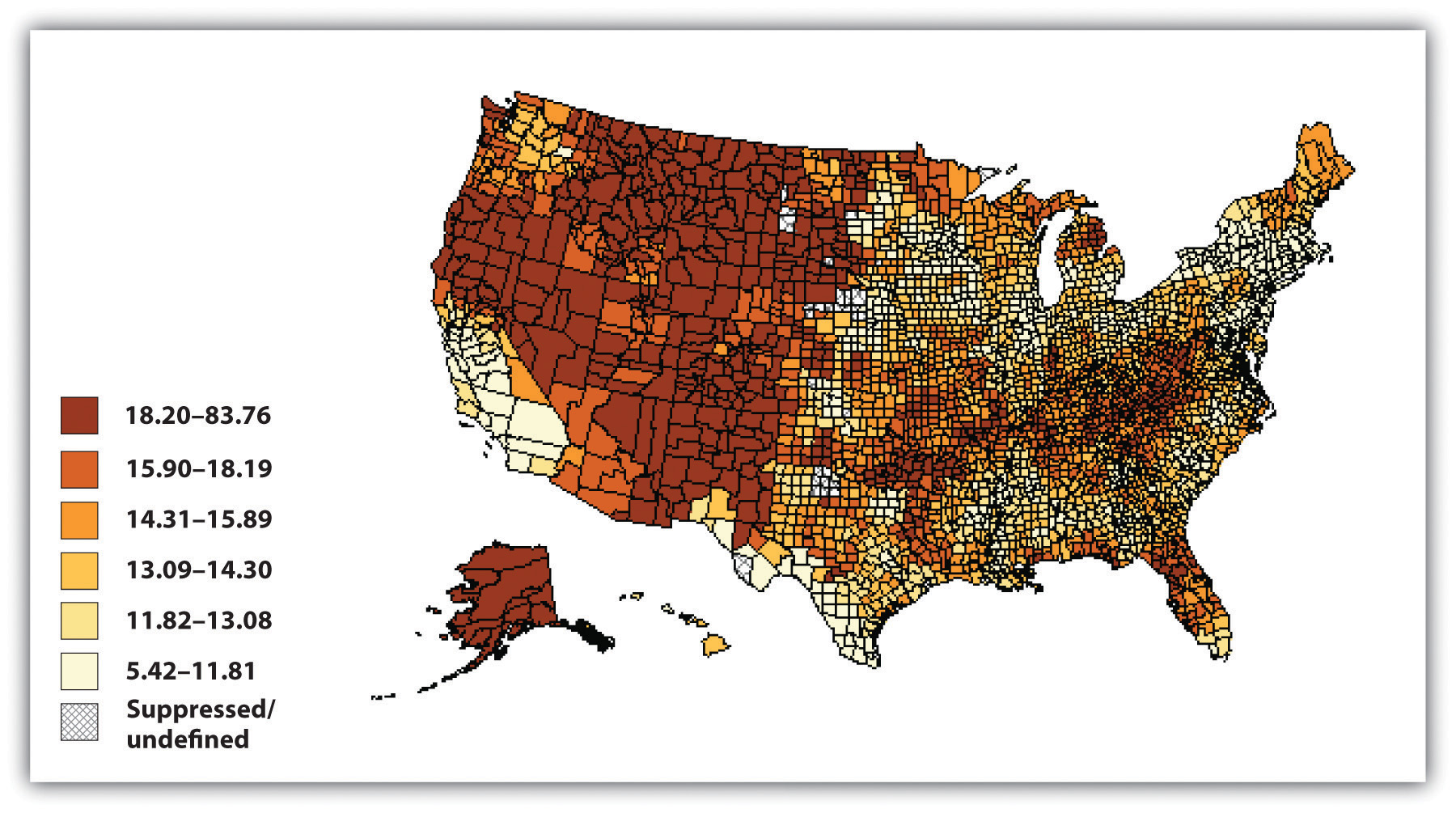

In this regard, consider what is perhaps the most personal decision one could make: the decision to take one’s own life. What could be more personal and individualistic than this fatal decision? When individuals commit suicide, we usually assume that they were very unhappy, even depressed. They may have been troubled by a crumbling romantic relationship, bleak job prospects, incurable illness, or chronic pain. But not all people in these circumstances commit suicide; in fact, few do. Perhaps one’s chances of committing suicide depend at least in part on various aspects of the person’s social background.