Sample details

- Government,

- Views: 2,071

Related Topics

- Sex education

- Intellectual property

- Vocational education

- Study skills

- Higher Education

- Technology in Education

- Importance Of College Edu...

- Physical Education

- United States

- Importance of Education

- Educational Goals

- Active listening

Democracy Without Education Is Meaningless

The importance of education in a democracy cannot be overstated, as it is what leads to progress and greatness. Unfortunately in India, the situation regarding education is distressing, with 60% of the population being illiterate. Adult education is necessary and can serve as an incentive to primary education. Social education is also needed to guide people in their leisure time and to avoid illiteracy and ignorance, which is a burden on society. Overcoming the difficulties of implementing adult education requires cleverness, fact, compromise, or intentional avoidance. The purpose of good teaching is to produce changes in human behavior and adult education emancipates people from illiteracy. It is important for citizens to be knowledgeable, for older individuals to keep their minds active, and for workers to be up-to-date on new techniques and technologies in a complex modern economy. Anyone, regardless of age, can go back to school and pursue their dreams related to their job through adult education programs.

Democracy without education is meaningless. It is education and enlightenment that lifts a nation to the heights of progress and greatness. Unfortunately, the situation as it obtains in India in respect of education is not only distressing but disgraceful and deplor? able. At present about 60% of the people in India are illiterate; they cannot differentiate a buffalo from a black mole. Adult education is needed because it is a powerful auxiliary and an essential incentive to primary education. No programme of compulsory universal education can bear fruit without the active support and co-operation of adults ocial educa? tion is needed in order to guide in spending their leisure in health? ful recreations and useful activities. Lastly, illiteracy and ignorance is a sin; an illiterate adult is a burden on society. A The difficulties have to be overcome either by cleverness, or by fact or by compromise, or may be, by intentional avoidance. Only then we can hope to spread Adult Education. The purpose of all good teaching is to produce changes in human behavior. All adult education teacher must adopt a positive approach; adult education emancipates people from the tyranny of illiteracy. 1] Some people, in their early age, did not have the chance to get education for different reasons. When they are old if then, they get education and they can discover themselves in a new way. [2] Learning is a continuous process, and if adult persons have the continued relationship with knowledge is also important. {3] Some adult much time to take rest but if they are engaged in learning they can also have fun and friends. {4] If they are busy something creative jobs, they will never feel boring rather they will feel healthier and happier.

We can implement it by making people people aware of it , starting campaigns and doing surveys . 1. in a complex modern democracy, citizens must be knowledgeable. 2. research shows that older people who keep their minds active suffer less dementia and other memory type diseases in old age. 3. in a complex modern economy, workers must be up-to-date on new techniques, and technologies Many people fail to understand that if they don ‘t make the extra effort, they ‘ll never be able to amount to much in life. Some however, after spending a ot of their time as kids fooling around, begin to make the effort to improve their status in life. So being well above thirty or even forty years doesn ‘t matter; anyone can still go back to school to study. It could be any degree that you want. Having missed out on education when you were yet young, still doing school might not look like a good option. However, there are so many adult education programs around, it would spin you in the head just thinking of it. You don ‘t have to give up on your dreamsrelated to their job.

ready to help you now

Without paying upfront

Cite this page

https://graduateway.com/democracy-without-education-is-meaningless/

You can get a custom paper by one of our expert writers

- English Language

- Online Education Vs Tradi...

- Free education

- Writing process

- Standardized Testing

- Constitution

- Growth Mindset

Check more samples on your topics

“ethical language is meaningless” discuss.

Firstly let me take the question itself- what exactly is ethical language? Dry Richard Paul defines ethics as "a set Of concepts and principles that guide us in determining what behavior helps or harms sentient creatures". Paul also states that most people confuse ethics with behaving in accordance with people's religious beliefs and the law,

The World Without an Education

In today's society many students experience obstacles, troubles, andfailure. However, the obstacles, troubles, and failure derive from ourirresponsible schools and families. When people think about schools in oursociety they perceive it to be a non-challenging atmosphere. Some studentsdiscover school to be very hard and mind boggling, when other studentsperceive school to be the worst thing

Can a Person Have a Successful Career Without College Education

Reasons To Go To College

Ellen DeGeneres has become one of the most popular comedians and television host with a net worth of $400 million. Although she did attempt to go to college at the University of New Orleans, she dropped out after only one semester. Many question if college education is really needed to become a successful individual. Anyone

Focus on John Dewey’s Democracy and Education

The Three Foundations of an Enlightened Society One of the major themes that comes up throughout John Dewey’s classic book on the philosophy of education is that the survival of an alive and vibrant democracy depends upon the educational development of its people. As Abraham Lincoln called it in his Gettysburg speech, democracy is a government

Veneration Without Understanding

Understanding

Dr. Jose Protacio Rizal Mercado y Alonzo Realonda, our national hero who is known for his nationalism and patriotism usually come side by side with these words; the doctor, the writer, the philosopher, the clairvoyant, and most of all the hero who died for the country. More than a hundred and fifty years ago, that

Life Without Light

“Life without light” Journal Article #3 “Life without light” Light is extremely important to this world. It is especially important to the food chains as it is the crucial source and starting point of it. Without light in the food chain it would be incomplete and plants and animals would have to get their source

How to Survive Without a Car

Losing your car in an accident can be a devastating experience, making it seem impossible to adapt to life without one. Concerns may arise regarding commuting, running errands, affording a new car, or maintaining social activities. The impact of losing a car can feel as profound as losing a limb. However, individuals with physical limitations

Imagining a World Without Computers

Appreciating the significance of computers is now easier because we can reflect on a world without them, even though they have not always been present.Computers have become an essential part of our everyday lives due to their increasing popularity and widespread accessibility. It is difficult to imagine life without them as they are now ingrained

Rebel Without A Cause

Adolescence

The movie “REBEL WITHOUT A CAUSE” is directed by Nicholas Ray, and is about a teenage boy named Jim Stark. Jim just moved into a new neighborhood, and he seems to be depressed because his family keeps moving from place to place because of Jim. This makes it really hard for Jim to have friends.

Hi, my name is Amy 👋

In case you can't find a relevant example, our professional writers are ready to help you write a unique paper. Just talk to our smart assistant Amy and she'll connect you with the best match.

Let’s educate tomorrow’s voters: Democracy depends on it

Subscribe to the center for universal education bulletin, elias blinkoff , elias blinkoff research scientist in the department of psychology and neuroscience - temple university molly scott , and molly scott research scientist - temple university kathy hirsh-pasek kathy hirsh-pasek senior fellow - global economy and development , center for universal education.

November 21, 2022

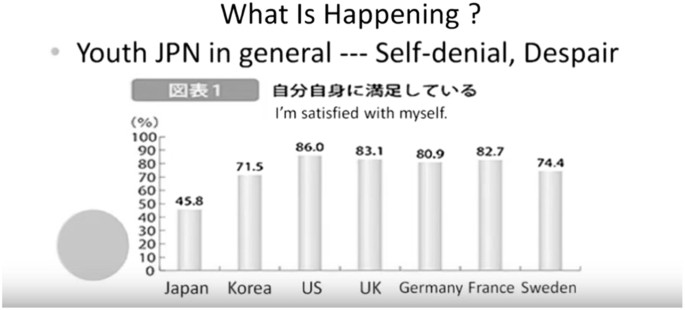

The final results of the 2022 midterm election in the United States are in. Journalists tell us that a key issue for voters was preservation of democracy . A recent NPR/PBS NewsHour /Marist poll showed that while inflation was the top issue on voters’ minds, “preserving democracy” captured second place. The issue that claimed little attention was education . Yet, as Thomas Jefferson once said, “An educated citizenry is a vital requisite for our survival as a free people.” That is, if we care about democracy, we must also care about education.

Only $ 10 million were spent on education ads by both parties between Labor Day and late October 2022, compared to $103 million spent on abortion ads by Democrats and $89 million spent on tax ads by Republicans. When education was discussed, political scientist Sarah Hill suggests that the topic was narrowly construed around culture war issues, including parental rights and ideologically-driven curriculum changes like banning books .

Sadly, conversation about education was limited in the most recent American election. We desperately need to ignite this discussion.

Given the lack of discussion around education, it is fair to repeat the claim made in 1983 that our nation is at risk . Now more than ever, the populous is required to sift truth from fiction among the many hyperbolic claims made by politicians on both sides. Without strong critical thinking skills, it is nearly impossible to manage the amount of content that people encounter every day and to form cogent opinions—be it on issues like health care, inflation, or climate change.

We are failing the next generation of citizens. Our recent Brookings blog on the latest National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) scores makes this point. It showed how students’ levels of proficiency in reading and math were already relatively low pre-pandemic, with the important qualifications that NAEP proficiency is not equivalent to grade level proficiency and a high academic standard to achieve. In fact, proficiency on the NAEP requires a deeper understanding of reading and math skills, including the application of critical thinking in relation to subject area content. And many reports suggest that even reaching proficiency (as defining success through the lens of just reading and writing) will not be enough to achieve Jefferson’s vision. Children need to learn a breadth of skills that includes—but goes beyond—content, to go from classroom to career success.

Our recent discussion of education facilitated by Brookings on November 9 following the launch of our book, “ Making Schools Work: Bringing the Science of Learning to Joyful Classroom Practice, ” explored a comprehensive, but flexible, framework for how to educate children with a breadth of skills—how to educate children to be caring, thinking, and creative citizens for tomorrow. Born from research in the science of learning , we suggest that we must teach in the way that human brains learn through an active (not passive) pedagogy that is engaging rather than distracting, meaningful with clear connections to prior lessons and students’ out-of-school experiences, socially interactive instead of entirely solo, iterative with room for experimentation and trial and error, and joyful rather than dull and repetitive. This is the antithesis of what is going on in many schools across the globe that were fashioned for a bygone era. If we do embrace a more modern educational model, students can be strong across the skills required to navigate school, work and society: collaboration , communication, content , critical thinking , creative innovation , and confidence (the ability to persist even after a failure and to know that you can grow with experience) .

Sadly, conversation about education was limited in the most recent American election. We desperately need to ignite this discussion. If our graduates are to outsmart the robots, to be viable for the job market, and to be discerning voters and citizens, education must literally be on the ballot. Yes, a major issue for voters this year was the precarious nature of our democracy. Our democracy, however, cannot survive if we do not educate our citizens. As The Atlantic proclaimed, “ Democracy was on the Ballot and Won .” If it is to keep winning, we must discuss education reform. Our science of learning can lead the way. It is imperative that children learn a breadth of skills that they can carry with them into the voting booth.

Related Content

Online only

10:00 am - 11:00 am EST

Rebecca Winthrop

June 4, 2020

Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, Jennifer M. Zosh, Roberta Michnick Golinkoff, Elias Blinkoff, Molly Scott

November 8, 2022

Early Childhood Education K-12 Education

Global Economy and Development

Center for Universal Education

Jonathan Rauch

September 6, 2024

September 5, 2024

Sana Sinha, Nicolas Zerbino, Jon Valant, Rachel M. Perera

October 10, 2023

Update on 2024-04-15

Democracy Cannot Survive Without Education

What is democracy.

Democracy is a form of government that depends on the active participation of its citizens. The success of democracy is not only dependent on free and fair elections but also on the education of its citizens. In this article, we will discuss the importance of education in a democratic society and how it affects the survival of democracy.

Importance of Education in a Democratic Society

Education plays a crucial role in the success and survival of democracy. It is through education that citizens learn about their rights and responsibilities, and how they can participate in the democratic process.

Education also helps citizens develop critical thinking skills, which are essential for making informed decisions and participating in public discourse.

Without education, citizens are more likely to be uninformed and disengaged from the democratic process. They may be more susceptible to propaganda and misinformation, which can undermine the integrity of the democratic system.

Moreover, an uneducated population may not be able to hold their leaders accountable, which can lead to corruption and abuse of power.

What are the Main Features of Democratic Education?

Democratic education is an educational approach that emphasizes active student participation, critical thinking, and civic engagement.

The main features of democratic education include:

- Active Student Participation: In democratic education, students are encouraged to take an active role in their learning. This means that they have a say in what they learn and how they learn it.

- Critical Thinking: Democratic education emphasizes critical thinking skills, which are essential for making informed decisions and participating in public discourse.

- Civic Engagement: Democratic education aims to prepare students for active citizenship. This means that they are encouraged to participate in their communities and take an active role in shaping society.

- Diversity and Inclusion: Democratic education values diversity and inclusion, and strives to create a learning environment that is welcoming and respectful of all students.

Relationship Between Education and Democracy

Education and democracy are inextricably linked. A democratic society requires an educated population that can engage in public discourse, make informed decisions, and hold their leaders accountable.

Conversely, education requires a democratic society that values the free flow of ideas, critical thinking, and the open exchange of information.

In countries where education is not accessible to all citizens, democracy is often undermined. The ruling class may use its power to limit access to education and control the flow of information, making it difficult for citizens to participate in the democratic process.

This can lead to social and economic inequality, as those without education are often unable to compete in the job market and access basic services.

Benefits of Democratic Education in India

Democratic education has many benefits in India, where education is often inaccessible to marginalized communities.

Some of the benefits of democratic education in India include:

- Increased Access to Education: Democratic education can help increase access to education for marginalized communities, ensuring that all citizens have the opportunity to participate in the democratic process.

- Critical Thinking: Democratic education emphasizes critical thinking skills, which are essential for making informed decisions and participating in public discourse. This can help citizens become more engaged in the democratic process and hold their leaders accountable.

- Empowerment of Marginalized Communities: Democratic education can empower marginalized communities by providing them with the tools and knowledge they need to advocate for their rights and participate in the democratic process.

- Promotes Social and Economic Equality: Democratic education can help promote social and economic equality by providing marginalized communities with access to education and the opportunity to compete in the job market.

Does Democracy Impact Illiteracy?

There is evidence to suggest that democracy can have a positive impact on illiteracy rates. In a democratic society, there is usually greater access to education, which can help reduce illiteracy rates.

In addition, democratic governments often prioritize education and invest resources in educational programs, which can lead to better educational outcomes.

Moreover, democracy can help empower marginalized communities, including those with low literacy rates. In a democratic society, all citizens have the right to participate in the democratic process, regardless of their level of education. This can help increase the political engagement of marginalized communities, leading to greater representation and access to resources.

Role of Education in Democracy

Education is the cornerstone of democracy. It empowers citizens with the knowledge and skills needed to participate in the democratic process, hold their leaders accountable, and make informed decisions.

Education is critical in fostering civic engagement, promoting critical thinking, and ensuring that citizens are informed about public policies and issues.

The following are some of the key roles of education in democracy:

- Fosters Active Citizenship: Education is essential for fostering active citizenship in a democratic society. It provides citizens with the knowledge and skills needed to participate in the democratic process, including voting, engaging in public discourse, and holding their leaders accountable. Educated citizens are more likely to be politically engaged and take an active role in shaping public policies and decisions.

- Promotes Critical Thinking: Education promotes critical thinking, which is essential for evaluating different viewpoints and making well-informed decisions. In a democracy, citizens need to be able to analyze information and ideas critically to make informed decisions. Education provides citizens with the critical thinking skills necessary to engage in public discourse and contribute to the democratic process.

- Ensures Informed Decision-Making: Education ensures that citizens are informed about public policies and issues. In a democracy, citizens need to have access to accurate and reliable information to make informed decisions. Education provides citizens with the knowledge and skills needed to analyze and evaluate information critically and make informed decisions.

What is the Impact of Democracy on Education?

Democracy has a significant impact on education. Democratic societies value education as a means of empowering citizens and promoting social and economic progress.

The following are some of the ways in which democracy impacts education:

- Equal Access to Education: In a democratic society, education is seen as a fundamental right that should be accessible to all citizens. Democratic governments prioritize education and ensure that all citizens have equal access to quality education, regardless of their social or economic status. This leads to more equitable education systems and reduces educational disparities.

- Emphasis on Critical Thinking: Democracy values critical thinking and informed decision-making, and this value is reflected in the education system. Democratic societies prioritize education that promotes critical thinking, analysis, and evaluation of information. This is essential for citizens to participate effectively in the democratic process and make informed decisions.

- Transparency and Accountability: Democracy values transparency and accountability in all aspects of governance, including education. Democratic governments ensure that the education system is transparent and accountable to citizens, with clear policies and procedures for decision-making and resource allocation.

How does Education Promotes Democracy?

Education promotes democracy by empowering citizens to participate in the democratic process. Citizens who are educated are more likely to vote, engage in public discourse, and hold their leaders accountable.

They are also more likely to understand the importance of the rule of law and the protection of individual rights.

Education also promotes social and economic mobility, which is essential for a healthy democracy. Citizens who are educated are more likely to have access to better job opportunities and higher wages, which can reduce social and economic inequality. This, in turn, can help promote social cohesion and stability, which are essential for the survival of democracy.

What is the Aim of Education in Democratic India?

In democratic India, the aim of education is to promote active citizenship, critical thinking, and social and economic progress.

The following are some of the objectives of education in democratic India:

- Citizenship Education: The primary aim of education in democratic India is to promote active citizenship. Education is designed to provide citizens with the knowledge, skills, and values needed to participate effectively in the democratic process. This includes promoting democratic values like freedom, equality, and justice.

- Social and Economic Progress: Education is also designed to promote social and economic progress in democratic India. Education is seen as a means of empowering citizens and reducing social and economic inequalities. The education system in India is designed to provide students with the skills and knowledge needed to compete in the global economy and promote innovation and entrepreneurship.

- Critical Thinking and Problem-Solving: In a democratic society, critical thinking and problem-solving are essential skills for active citizenship. Education in democratic India is designed to promote critical thinking, analysis, and evaluation of information. This is essential for citizens to participate effectively in the democratic process and make informed decisions.

Democracy cannot survive without education. Education plays a crucial role in the success and survival of democracy by empowering citizens to participate in the democratic process, promoting critical thinking, and reducing social and economic inequality.

It is, therefore, essential that governments invest in education and ensure that all citizens have access to quality education. Only then can we ensure that democracy remains a vibrant and thriving form of government that serves the interests of all citizens.

Related Articles

Manipal University Online MBA Admission 2024 | Last Date, Application Form, Fee, Eligibility and Syllabus

10 Best NDA Coaching in Coimbatore 2024: Check Admission, Fees, Duration and Syllabus

MBA Admission Without CAT: How to Get Direct Admission in Top Govt. & Private Colleges

How to Build a Strong Profile for MBA | Improve your MBA Profile

Trending News

UP BEd Application Form 2024 - Online Apply UP BEd Registration Form

RRB Health and Malaria Inspector Recruitment 2024: Exam Dates, Application Process, Syllabus, Results, & Others

Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA) Recruitment 2024: SSA Recruitment 2024

Annamalai University Result 2024 - Check Here Annamalai University Result, Marks, and, Percentage

Trending Articles

Top 10 Interior Designing Colleges in Gurgaon

Fashion Designing Course in Delhi NCR

Top 10 Hotel Management Colleges in Noida

Top 10 Fashion Designing Colleges in Chandigarh

Best Coachings In India

- Best NDA Coaching in Jaipur

- Best CAT Coaching in Jaipur

- Best UPSC Coaching in Prayagraj

- Best NDA Coaching in Prayagraj

- Best NEET Coaching in Jaipur

- Best UPSC Coaching in Jaipur

- Best NEET Coaching in Prayagraj

- Best IIT JEE Coaching in Jaipur

- Best CLAT Coaching in Prayagraj

- Best NEET Coaching in Varanasi

Best Career Counselling In India

- Career Counselling in Delhi

- Career Counsellor in Bangalore

- Career Counsellor in Mumbai

- Career Counsellor in Chennai

- Career Counsellor in Hyderabad

- Career Counsellor in Jaipur

- Career Counsellor in Gurgaon

- Career Counsellor in Bhopal

- Career Counsellor in Delhi Ncr

- Career Counsellor in Greater Noida

- Privacy policy

- Refund & Cancellation

- Terms & Conditions

- Write for US

Copyright @2024. www.collegedisha.com . All rights reserved

OPINION article

Learning for democracy: some inspiration from john dewey's idea of democracy.

- Center of Teacher Education, Minghsin University of Science and Technology, Hsinchu, Taiwan

1 Introduction

Citizens in a democracy must be educated because it is they who steer the ship of state ( Dar, 2021 ). Therefore, for a country to progress toward democracy, people need to be nurtured with democratic literacy through education. The ideas of John Dewey, a 20th Century American philosopher, are highly influential on our contemporary understanding of this relationship between education and democracy. He was born on October 20, 1859, in Burlington, Vermont, in the United States. After graduating from the University of Vermont in 1879, he taught in Vermont until 1881 and in high school in Pennsylvania until 1882. He received a doctorate from Johns Hopkins University in 1884. He died on June 1, 1952. Dewey is known for his views on the relationships between philosophy, education, democracy, the society, and the individual ( Özkan, 2020 ).

In Democracy and Education , Dewey criticizes dichotomies such as those between reason and experience, intelligence and physical strength, liberal education and practical training, the sciences and the humanities, and the spiritual and the material. He believed that history had affirmed the former at the expense of the latter of these dichotomies, and such an imbalance hinders social progress. Thus, Dewey adopted an empiricist foundation and argued that ideally, science and labor ought to carry both practical and humanistic value in a society. In the preface of Democracy and Education, Dewey explored and explained the various ideas constituting a democratic society and the application of these ideas to various issues in education ( Dewey, 1916 ; Tampio, 2024 ).

Dewey's writings continue to influence discussions on a variety of subjects, including democratic education , which was the focus of Dewey's famous 1916 book on the subject ( Dewey, 1916 ; Tampio, 2024 ).

Dewey believed that democracy means that every human being, independent of the quantity or range of his personal endowment, has the right to equal opportunity with every other person for development of whatever gifts he has. Dewey's vision of education is teachers nurturing each child's passions and not using tests to rank children. School curriculum develop talent in every student—nurture by nature. However, some schools are far from realizing that vision ( Dewey, 1916 ; Shih, 2024 ; Tampio, 2024 ). Therefore, this article explores John Dewey's idea of democracy and his conception of the role of learning in developing a democratic learning atmosphere, and emphasizes a democratic education allows students to participate in the problem–solving process, that continuous use of real social issues enhances democratic literacy for students ( Ye and Shih, 2021 ).

2 Research method

This study uses a critical hermeneutic approach to understand Dewey's idea of democracy, which is a key pillar of his thought. Many scholars have studied his earlier and well-known works, The School and Society and Democracy and Education ( Dewey, 1899/1976 ; Shih, 2018 ; Saito, 2020 ).

3 Dewey's idea of democracy and how it inspires learning for democracy

3.1 students are socialized into a democratic way of life through education.

In the preface of Democracy and Education , Dewey states that he aimed to provide “a critical estimate of the theories of knowing and moral development which were formulated in earlier societies, but still operate… to hamper the adequate realization of the idea of democracy.” He argues that the realization of democracy is closely related to epistemic and moral development, upon which the society and its educational system are based. Dewey implied that for education to be truly democratizing, the theories of knowledge and moral development underpinning education must be aligned with a democratic way of life ( Dewey, 1916 ; Lind, 2023 ). In addition, students must be socialized into a democratic way of life ( Shih, 2020 ).

3.2 Students gain opportunities and resources to realize their potential by participating in political, social, and cultural life

Dewey fiercely advocated for participatory democracy: the belief that democracy as an ethical ideal calls upon men and women to build communities in which every individual has the necessary opportunities and resources to realize his or her potential by participating in political, social, and cultural life. This also extends to students ( Dewey, 1916 ; Peters and Jandrić, 2017 ).

3.3 Teachers should respect diversity in their students' way of being

Dewey's vision of democracy challenges us to adapt our global communities and educational systems according to the needs of our historical moment for all citizens to benefit. Dewey called on the citizens of democratic societies to imagine new ways of association and interaction that foster respect for freedom, equality, and the diversity in our ways of being in the world. Similarly, teachers should respect diversity in their students' way of being for students to flourish as human beings ( Dewey, 1916 ; Gordon and English, 2016 ; Ye and Shih, 2021 ).

3.4 The ability of students to exercise their judgment is honed through democratic education

Dewey stressed that education must prepare students for an uncertain future. Indeed, we face such a future given the speed of economic and technological change today. Thus, students must develop effective habits, be adaptable, and learn how to learn. This contrasts with a traditional, industrial model of education where individuals are trained to fulfill a single occupational niche for the rest of their lives ( Dewey, 1916 ; Stobie, 2024 ).

Dewey expanded the concept of democracy to mean something abstract to something that encompasses the entirety of human life. Correspondingly, education became increasingly entwined in such a conception of democracy. As noted by Dewey, most people think of democracy as a political institution, made most visible by the act of voting. However, voters ought to make an informed choice, and they can only do so through keen judgment, which is cultivated through education ( Dewey, 1916 ; Ye and Shih, 2021 ).

4 Discussion

Maintaining democracy and freedom is key to the future of the post-totalitarian countries that emerged 30 years ago from their isolation from the West to reclaim the place where they had historically belonged ( Strouhal, 2020 ).

The dialectical relationship between democracy and education for democracy reflects the fluid natures of both democracy and education. Fluctuations within the internal dynamics of democratic institutions and relations between democracy and society can reflect progress, a deepening of democracy, or setbacks. As a result of such flux, the relationship of democracy to education evolves as does democracy itself, necessitating periodic reexamination so that efforts to align educational institutions with democratic goals remain relevant ( Reimers, 2023 ).

In addition, the sustainability of a country depends on the quality of the next generation, which plays a vital role in various aspects of life, ranging from education, culture, economy, politics, and religion. Education can build a new generation of a nation toward a better direction. All nations worldwide are trying to prepare the next generation of good and smart citizens. Carrying the spirit of democracy, all nations worldwide emphasize organizing a good governance government and focusing on the involvement of its citizens ( Fuad, 2023 ).

Dewey's “ Democracy and Education ” is commendably guided by the vision of a democratic society. He contrasts the democratic society with an undesirable society “which internally and externally sets up barriers to free intercourse and communication of experience”. By contrast, a democratic society “secures flexible readjustment of its institutions through interaction of the different forms of associated life” and “makes provision for participation in its good of all its members on equal terms”. Dewey proposed two metrics “to measure the worth of a form of social life” by: “the extent in which the interests of a group are shared by all its members, and the fullness and freedom with which it interacts with other groups” ( Dewey, 1916 ; Papastephanou, 2017 ).

Finally, Dewey defined education in Democracy and Education as “that reconstruction or reorganization of experience which adds to the meaning of experience, and which increases ability to direct the course of subsequent experience.” ( Dewey, 1916 ). Hence, education must be based on experience, developing and expanding the growth of experience from individuals' real-life experiences. Since each experience can have either a positive or negative impact on each person, the attitudes formed can lead to preferences or aversions, and the value of an experience can be inferred from the direction it drives. The transformation of experience has educational significance only when it develops positively. Therefore, teachers should promote education in a democratic manner, allowing students to gain experiences of democratic education. In this way, students are more likely to develop democratic literacy. And, our society is more likely to become a democratic society.

5 Conclusions

Autonomous citizens participating in a free society (i.e., a democracy) cannot be cultivated in a regimented, one-size-fits-all classroom. Students should thus be given enough space to continually experience life and establish their values. Dewey argued that education, both formal and informal, should be organized to promote individual and social growth. These ends are most likely to be achieved when learners work together and focus on crucial problems relevant to their lives ( Harbour, 2023 ).

Such education is the bedrock on which a democracy thrives, where democratic processes and practices extend beyond the political into the social and economic ( Harbour, 2023 ). Such education can also only function in a society where democratic ideals (that every young citizen ought to be socialized into becoming thinking participants of a free society) are cherished. Thus, education and democracy are parasitic on each other in Dewey's worldview ( van der Ploeg, 2019 ).

Through the decades, Dewey's focus increasingly shifted toward the importance of learning to think critically, including interrogating existing social structures and dynamics ( van der Ploeg, 2019 ). We glean the following points from Dewey's conception of democracy and education. (1) Education should socialize students into a democratic way of life. (2) Students should be given opportunities and resources to realize their potential by participating in political, social, and cultural life. (3) Teachers should respect the diversity in their students' ways of being. (4) Democratic education should hone the ability of students to exercise their judgment. (5) Education in a democracy should aim to “continuously reorganize and transform the experiences” of students. We hope that, through our article, educators and stakeholders can appreciate the centrality of democratic education in a democratic society.

Author contributions

Y-HS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by the Taiwan's Ministry of Science and Technology (Grant No. 104-2410-H-254-001-).

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Dar, R. A. (2021). Educational philosophy of John Dewey and his main contribution to education. Int. J. Adv. Multidiscipl. Sci. Res. 4, 12–19. doi: 10.31426/ijamsr.2021.4.9.47120

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Dewey, J. (1899/1976). “The school and society,” in The Middle Works of John Dewey , ed. J. A. Boydston (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press).

Google Scholar

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and Education . New York: The Macmillan Company.

Fuad, V. (2023). Relationship between young citizens democracy education and good governance. Int. J. Educ. Qualit. Quant. Res . 2, 35–41. doi: 10.58418/ijeqqr.v2i1.41

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

Gordon, M., and English, A. R. (2016). John Dewey's democracy and education in an era of globalization. Educ. Phil. Theory 48, 977–980. doi: 10.1080/00131857.2016.1204742

Harbour, C. P. (2023). “John Dewey: education for democracy,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Educational Thinkers , ed. B. A. Geier (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan).

Lind, A. R. (2023). Dewey, experience, and education for democracy: a reconstructive discussion. Educ. Theory 73, 209–319. doi: 10.1111/edth.12567

Özkan, U. B. (2020). “Curriculum development model of John Dewey,” in Current Researches in Educational Sciences , eds. A. Doǧanaym and O. Kutlu (Ankara: Akademisyen Kitabevi A.S.), 23–37.

Papastephanou, M. (2017). Learning by undoing, democracy and education, and John Dewey, the colonial traveler. Educ. Sci . 7:20. doi: 10.3390/educsci7010020

Peters, M. A., and Jandrić, P. (2017). Dewey's democracy and education in the age of digital reason: the global, ecological and digital turns. Open Rev. Educ. Res. 4, 205–218. doi: 10.1080/23265507.2017.1395290

Reimers, F. M. (2023). Education and the challenges for democracy. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 31:102. doi: 10.14507/epaa.31.8243

Saito, N. (2020). “John Dewey (1859–1952): Democratic hope through higher education,” in Philosophers on the University. Debating Higher Education: Philosophical Perspectives , eds. R. Barnett, and A. Fulford (Cham: Springer).

Shih, Y. H. (2018). Some critical thinking on Paulo Freire's critical pedagogy and its educational implications. Int. Educ. Stud. 11, 64–70. doi: 10.5539/ies.v11n9p64

Shih, Y. H. (2020). Encounter with Paulo Freire's critical pedagogy: Visiting the Brazilian social context (1950s-1970s). Univer. J. Educ. Res . 8, 1228–1236. doi: 10.13189/ujer.2020.080413

Shih, Y. H. (2024). Children's learning for sustainability in social studies education: a case study from Taiwanese elementary school. Front. Educ. 9:1353420. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1353420

Stobie, T. (2024). Reflections on the 100th year Anniversary of John Dewey's ‘Democracy and Education' . Available online at: https://blog.cambridgeinternational.org/reflections~-on-the-100th-year-anniversary-of-john-deweys-democracy-and-education/ (accessed March 26, 2024).

Strouhal, M. (2020). On the current problems of education for democracy. J. Pedag. 11, 73–87. doi: 10.2478/jped-2020-0012

Tampio, N. (2024). Why John Dewey's Vision for Education and Democracy Still Resonates Today . Available online at: https://theconversation.com/why-john-deweys-vision-for-education-and-democracy-still-resonates-today-222849 (accessed March 26, 2024).

van der Ploeg, P. A. (2019). “Dewey and citizenship education: schooling as democratic practice,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Citizenship and Education , eds. A. Peterson, G. Stahl, and H. Soong (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan).

Ye, Y. H., and Shih, Y. H. (2021). Development of John Dewey's educational philosophy and its implications for children's education. Policy Futures Educ. 19, 877–890. doi: 10.1177/1478210320987678

Keywords: democracy, education, educational philosophy, John Dewey, learning for democracy

Citation: Shih Y-H (2024) Learning for democracy: some inspiration from John Dewey's idea of democracy. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1429685. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1429685

Received: 08 May 2024; Accepted: 13 June 2024; Published: 27 June 2024.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2024 Shih. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yi-Huang Shih, shih262@gmail.com

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Education and Democracy

- Martha Minow

Anna Deavere Smith, American actress, playwright, and professor, once said , “Art convenes. It is not just inspirational. It is aspirational. It pricks the walls of our compartmentalized minds, opens our hearts and makes us brave.” In that spirit, can we “prick the walls of our compartmentalized minds” and bring heart and courage to reflections on education and democracy? Democratic governance in societies around the world faces serious challenge today. Education sits at the crossroads of the information revolution and widening inequalities. The frailties of education increase the fragility of democracy. Strengthening each is critical to the other.

What steps move toward strength, and what steps instead make matters worse?

Democracy is hard work, and often produces poor policies. Playwright George Bernard Shaw was not stretching the truth when he had one of his characters say , “Democracy substitutes election by the incompetent many for appointment by the corrupt few.” The work of self-governance takes time, produces conflicts, and leaves us with few to blame but ourselves. So, it “ is the worst form of Government except all those other[s]. ”

On top of it all, it’s difficult to keep a democracy. Elections can be rigged. Politicians can take choices away from the voters. And the people can be tempted to surrender their power — by failing to vote or by voting for tyrants. Only 4.5% of the world’s populations live in full democracies, and even in those nations, self-governance faces rising gains by authoritarian leaders in Venezuela, Poland, Hungary, the Philippines, and, some would say , the United States.

The founders of the United States understood that “ an ignorant people cannot remain a free people and that democracy cannot survive too much ignorance. ” The American movement for “common schools” initiated in the 1830s sought to promote political stability, equip more people to earn a living, and enable people to follow the law and transcend differences in religion and background. Yet we are far from embracing this ideal as a guide for practice in the United States. As initially advanced, the common school ideal excluded enslaved people and children with disabilities. After the Civil War — and even today — public school systems still often divide students by race and class in practice.

A sustained legal strategy attacking legally mandated racial segregation in schools yielded official victory in 1954. But this also triggered resistance, and, despite some successes, massive racial separation persists in American schools. According to work done by Jennifer L. Hochschild and Nathan Scovronick , of this country’s 5,300 communities with fewer than 100,000 people, at least ninety percent were white at the turn of this century. In large urban districts, nearly seventy percent of the public students were nonwhite, and over half were poor or nearly poor. In some communities , this pattern has continued to worsen. Disparities in per-pupil expenditures further reflect the sharp differences in local wealth because most of the country funds schools based on local property taxes. Although a majority of Americans report that school integration is a good idea, a majority also agree that “ we shouldn’t do anything to promote [it] .” One commentator reports that now we live in an era of “hoarding” by upper middle-class families — those in the top twenty percent of income — who have used zoning laws, local control of schooling, college application procedures, and unpaid internships to pass their opportunities onto their children while making it harder for others to break in.

As a result, it is fair to ask whether we are holding up the ideal, so well stated by John Dewey , that schools should “see to it that each individual gets an opportunity to escape from the limitations of the social group in which he was born, and to come into living contact with a broader environment”? Controversial policy reforms would increase educational opportunities for disadvantaged students, but there is little political will for paying teachers more to teach in schools in poor neighborhoods, making higher education truly affordable, ending exclusionary residential zoning, and replacing reliance on local property taxes with state-wide or national redistributive financing.

To work, democracy needs effective schools that do even more than instruct students in the value and institutions of a democratic society (though this would be a good start, given that in 2014 only 36% of Americans could name the three branches of government ). Schools can cultivate habits and skills of taking initiative, showing respect, listening, and controlling emotions in the face of disagreement. Schools can help individuals take the perspective of others and learn to assess and organize information. These capacities are presumed by democratic governance, but children are not born with these abilities. Nor are they born with knowledge of what life is like under fascism or autocracies. Students can learn by doing: learn to use the tools of democracy in their classrooms, debate controversial issues, and practice disagreeing with respect. Schools can trust young people to follow their own interests, to take responsibility, and to take up governance of their own classrooms and lives. Civics education with these features leads to greater political engagement, voting , and higher degrees of acceptance toward people of different backgrounds .

At this moment, the distance between these ideals and aspirations much less actual practices around the country is enormous. A global study found that few millennials object to autocracy; only 19% of American millennials surveyed report that a military takeover would be illegitimate if the government is incompetent. Not many young people may know how following a worldwide economic depression, people in Italy and Germany turned to fascism in the 1930s and gave power to Mussolini and to Hitler . Mussolini and Hitler appealed to racism, fanaticism, and fear — and created global violence, mass killings, and destruction of communities and democratic ideals. A ray of hope for democracy: survey research suggests that people are much more willing to deliberate than prior research suggested, and those most willing to deliberate are exactly those turned off by standard, polarized, interest group politics. If the conventional avenues for participation can involve more opportunities for deliberation, many who are disengaged and disaffected might join in the work of self-governance.

Digital resources offer both promise and risks for education, for democracy, and for their connections. The Internet, social media, and search engines bring much of the world’s knowledge within reach of more people than ever in human history. Information — and disinformation — are plentiful and a few keystrokes away. It is more difficult for repressive regimes to keep information out of people’s reach. The architecture of the Internet also enables people with little cost to find others with similar interests, to share and spread information and views, and to recruit others because it facilitates one-to-many communication . These features are exemplified by the work of MoveOn and Breitbart News — and also by terrorist recruitment and sexual predators online. Arab Spring and public protests in Turkey indicate the power of the Internet to promote democracy but authoritarian governments have also found the Internet useful for surveillance, intimidation, and purging opposition . Research suggests that some individuals tune out of politics with the help of social media and internet entertainment , but here the internet simply joins many opportunities for people to avoid political engagement. Both education and democracy are fragile unless people desire — and fight for — political participation, knowledge, debate, critical reasoning, and freedom, whether in governance of their societies, schools, or design of the Internet.

Education and democracy both enhance human freedom but require rules and structure to work. Both need ground rules. Neither can work amid untrammeled violence, disrespect, and lying. Formal rules and informal norms can guide people to assess claims and bolster intolerance of intolerance. Practicing the predicates of education and democracy — the norms of respect and truth — these are the tasks pricking the walls of our compartmentalized minds, opening our hearts, and making us brave.

This post is based on remarks given at Sarah Lawrence College.

More from the Blog

Courts should hold social media accountable — but not by ignoring federal law, tech companies’ terms of service agreements could bring new vitality to the fourth amendment.

- Brent Skorup

Criminalizing Community, Policing Space: Conspiracy, Young Thug & the “Stop Cop City” Protestors

- Cynthia Godsoe

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Original Language Spotlight

- Alternative and Non-formal Education

- Cognition, Emotion, and Learning

- Curriculum and Pedagogy

- Education and Society

- Education, Change, and Development

- Education, Cultures, and Ethnicities

- Education, Gender, and Sexualities

- Education, Health, and Social Services

- Educational Administration and Leadership

- Educational History

- Educational Politics and Policy

- Educational Purposes and Ideals

- Educational Systems

- Educational Theories and Philosophies

- Globalization, Economics, and Education

- Languages and Literacies

- Professional Learning and Development

- Research and Assessment Methods

- Technology and Education

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Democracy and education in the united states.

- Kathy Hytten Kathy Hytten University of North Carolina at Greensboro

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.2

- Published online: 29 March 2017

There is an integral and reciprocal relationship between democracy and education. Democracy is more than a political system or process, it is also a way of life that requires certain habits and dispositions of citizens, including the need to balance individual rights with commitments and responsibilities toward others. Currently, democracy is under threat, in part because of the shallow and reductive ways it has been taken up in practice. Understanding the historical relationship between democracy and education, particularly how democracy was positioned as part of the development of public schools, as well as current approaches to democratic schooling, can help to revitalize the democratic mission of education. Specifically, schools have an important civic role in cultivating in students the habits and dispositions of citizenship, including how to access information, determine the veracity of claims, think critically, research problems, ask questions, collaborate with others, communicate ideas, and act to improve the world. Curriculum, pedagogy, and organizational structures are unique in democratic schools. Developing an active, inquiry-based curriculum; using a problem-posing pedagogy; and organizing schools such that students develop habits of responsibility and social engagement provide our best hope for revitalizing democracy and ensuring that it is not simply an empty slogan but a rich, participatory, justice-oriented way of life.

- United States

- social justice

- democratic schools

- purposes of education

- civic education

If we were to ask a typical citizen in the United States about the meaning of democracy, they would likely tell us that it is a political system that entails freedom, choice, and voting. They would have some familiarity with branches of the government, the electoral process, and the idea that citizens get to choose their leaders. They have probably learned that democracy is the best system in the world, especially in contrast to other possibilities, such as communism, socialism, totalitarianism, and oligarchy. They may point out how democratic societies allow individuals to do what they want, provide myriad consumer choices, and ensure opportunities for everyone who works hard to be successful, often implicitly conflating capitalism and democracy. Most likely, they take democracy for granted; it is simply the name for our way of life. Yet at the same time, the idea of democracy is fragile and contested and, from a global perspective, increasingly suspect. Democracy has been invoked to support a range of questionable practices, including invading foreign countries, declaring wars, exploiting the environment, and placing the needs of corporations above those of people. Democracy is called upon as the justification “for almost anything people want to do” (Beane & Apple, 2007 , p. 6), leading many around the world to worry “that an appeal to democracy is a veiled attempt by those making the appeal to dominate, to manipulate, or in other ways to advance their own interests at others’ expense” (Ryder, 2007 , para. 1). Ironically, the more democracy is called upon, the less we seem to agree on what it means, and the more empty an idea it becomes.

In this article, I offer a rich vision of democracy as a way of life and describe the role of education in supporting that vision. In contrast to a shallow view of democracy as merely a political process, I argue that democracy is an ethical ideal that must be deliberately fostered and nourished in order for it to survive. It is ever a work in progress, and the fundamental role of schools in democratic societies is to cultivate the habits, values, dispositions, and practices necessary to sustain a democratic way of life. Since the creation of public schools in the United States centuries ago, they have always served a civic mission, though the centrality of this mission has waxed and waned. In our current climate of high-stakes accountability, excessive international competition, and privatization of public goods, we have arguably lost sight of the crucial relationship between education and democracy. In order to revitalize the civic mission of public education, we must understand the meaning of democracy and the role of schools in teaching, modeling, and sustaining a democratic way of life.

I begin this article by defining democracy as a way of life that requires certain habits and dispositions of citizens, including the need to balance individual rights with commitments and responsibilities toward others. I then discuss some of the current threats to democracy, including the ambiguity surrounding its meaning, and the reductive ways in which it is interpreted in practice. Third, I describe the historical relationship between education and democracy, exploring how this relationship has developed over time. I focus especially on the ideas of John Dewey, as he dedicated so much of his philosophical work to detailing the intimate and reciprocal connections between democracy and education. Fourth, I make an argument for the role democracy should play in our thinking about education contemporarily, describing the civic habits and dispositions that schools should cultivate if democracy is to hold any meaning. Fifth, I sketch some visions for democratic schooling that can help to revitalize and sustain a democratic way of life, arguing that a way of life as fragile and precarious as democracy can only survive when schools equip young people, as citizens in the making, with the skills, knowledge, and dispositions needed to nourish it. I describe approaches to curriculum, pedagogy, and school organization that can best cultivate democratic habits and behaviors. I close by suggesting that thinking deeply about the relationship between democracy and education is critical to bringing about a more just, fulfilling, and peaceful world.

What Is Democracy?

Describing the meaning of democracy is a more difficult task than it might initially seem. Most of us learn that democracy is a “form of political governance involving consent of the governed and equality of opportunity” and that it involves direct participation in some activities in our society, including electing representatives who will speak and work on our behalf in others (Beane & Apple, 2007 , p. 7). We may also consider it a way of social and political organization, involving rules, laws, prohibitions, and rights, encapsulated in such documents at the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights. The word democracy comes from the Greek root demos , which means the population of a town or nation. Building on this root, Kohl ( 1992 ) writes that, “a democracy is a society in which the population rules, not royalty, not a small number of families, or the military” (p. 201). Yet exactly how the people rule, and who constitutes “the people,” are matters of ongoing debate. Historically, many people were excluded from democratic participation, including women, people from minority groups, slaves, and men who didn’t own land. Moreover, there are multiple ways in which people can be involved in governing themselves, from directly participating in deliberation and decision-making on a face-to-face level to voting for people whom they implicitly trust will make choices that are in their best interest. Held ( 2006 ) claims that the idea of democracy is contested and that key democratic ideas and ideals are sometimes ambiguous and inconsistent, including “the proper meaning of ‘political participation,’ the connotation of ‘representation,’ the scope of citizens’ capacities to choose freely among political alternatives, and the nature of membership in a democratic community” (p. x).

Describing the relationship between democracy and education is particularly challenging because there is only loose consensus on the meaning of democracy itself, and there are different forms of democracy in practice. Held ( 2006 ) identifies nine different (though often overlapping in important ways) models of democracy that have evolved over time: developmental republicanism, protective republicanism, protective democracy, developmental democracy, legal democracy, competitive elitist democracy, deliberative democracy, participatory democracy, and pluralism. Gabardi ( 2001 ) adds communitarian democracy and agonistic democracy to this list, while Biesta ( 2007 ) describes different ways of conceiving democratic subjectivity including individual, social, and political. Acknowledging the range of possibilities and practices, Dahl ( 2015 ) nonetheless argues that heart of democracy involves a belief in the political equality of citizens and that actualizing this belief requires, at a minimum, equal and effective opportunities for civic participation, voting equality, equal and effective opportunities to learn about a range of options and their potential consequences (what he calls “enlightened understanding”), citizen control of issues that get placed on the policymaking agenda, and inclusion of all adults as citizens in all matters that affect them.

Perhaps even more important than a political process, democracy is also a way of life, it is “both an ideal and an actuality” (Dahl, 2015 , p. 26), marked by values and practices that are complex, contested, and varied. In his well-known and often-cited description of democracy, John Dewey ( 1916 ) writes that it “is more than a form of government; it is primarily a mode of associated living, of conjoint communicated experience” (p. 93), whose contours require regular discussion, assessment, and reinvention. Dewey goes on to suggest democracies are built upon the collaborative interdependence of people in a society who identify shared interests, work together to solve problems, and create ways of living together that bring out the best in everyone. We value democratic social arrangements because they offer us “the promise of freedom and self-determination in the context of shared commitment to the public good” (Gallagher, 2008 , p. 340). Yet there are always tensions, challenges, and conflicts among values in democratic societies. Among the most significant of these tensions is how we balance a commitment to autonomy alongside at least some minimal obligations to other people. One of the hallmarks of democratic societies is that they work to maximize individual liberty and autonomy, protecting the ability of individuals to advance their own interests without imposing upon them a singular vision of a good life. Liberal democratic theorists are thus “preoccupied with the creation and defense of a world in which ‘free and equal’ individuals can flourish with minimum political impediments” (Held, 2006 , p. 262). Alternatively, leftist, radical, and socialist-oriented democratic theorists worry about overly individualistic conceptions of democracy and defend the need for more collective orientations and intervention by states so as to ensure equality among citizens in reality, not just theory. The tension between liberty and equality never simply goes away; indeed, Mouffe ( 2009 ) claims this paradox is constitutive of democratic societies, it is “a tension that can never be overcome but only negotiated in different ways” (p. 5). Democratic educational theorists adopt a range of positions on the spectrum between liberal and leftist perspectives on the relationship between democracy and education, with many arguing that in our current era, and given existing threats to democracy, we need to reinvigorate our concern for common, not just individual, goods.

While understanding government systems and political processes is necessary for peaceful citizenship, the founders of democracy had grander ideals than simply creating laws for people to vote upon and follow. Rather, in the vein of Dewey, they believed that democracy was a way of life that involved values, principles, beliefs, and habits of being. Arguing from the more leftist perspective, Beane ( 2005 ) describes this way of life well. He maintains that democracy is ultimately an idea about how people can live together in ways that are equitable, just, enriching, and fulfilling. At the heart of democracy are two ideas: “that people have a fundamental right to human dignity and … that people have a responsibility to care about the common good and the dignity and welfare of others” (p. 9). The right to dignity requires the ability to access to information, think for oneself, decide how to live one’s life, be free from coercion, and pursue happiness. At the same time, as part of one’s responsibility toward others, we are compelled to care about common goods, work together to solve problems, participate in discussion, and improve our collective well-being. These ideas provide some “guidelines” and a moral compass for how people can “live and learn to work together democratically” (Beane, 2005 , p. 120). Yet in popular understanding, we have typically decoupled rights from responsibilities and lost sight of the centrality of common goods and commitments to others as an integral part of democratic living. In its most crass and neoliberal forms, democracy has too often come to mean celebration of individual self-interest. That is, as long as I obey laws, pay taxes, vote periodically, and don’t intentionally harm others, I can do pretty much anything that I want.

To challenge reductive, narrow, and overly individualistic and neoliberal visions of democracy, it is useful to consider it as an ethical, social, and political ideal—a dynamic work in progress. Minimally, argues Gutmann ( 1999 ), democracy entails the principles of nondiscrimination and nonrepression. In its ideal from, democracy involves the cultivation of individual characteristics and habits of being, such as caring, compassion, generosity, fairness, respect, imagination, courage, kindness, and cooperation. Concurrently, it requires that citizens create communal systems and arrangements that support inquiry, problem solving, diversity, and ongoing efforts at social reform. It involves both dispositions toward others and everyday practices, like listening, questioning, participating, and experimenting. An open flow of ideas and equitable access to information are necessary in democratic societies, even when that information may be unpopular, as this openness is imperative if people are to make informed decisions about issues that affect their lives (Beane & Apple, 2007 , p. 7). Democratic citizens value diversity and believe a range of ideas, worldviews, and perspectives is enriching and important. Indeed, the valuing of diversity and pluralism are central features of democratic societies, because in diversity there is strength. Moreover, they require that citizens actually at least minimally care about the welfare of others who are different from them and want to uncover social problems, work to solve these problems, and pursue peaceful means for navigating conflicts.

On the one hand, democracy is of course a political system, yet ideally, on the other hand, citizens come to view it as much more than that, seeing it more foundationally as a “creative, constructive process” that we need to nurture and protect, “a trek that citizens in a pluralistic society make together … a political path, a tradition of sorts, that unites them, not a culture, language, or religion” (Parker, 2003 , p. 21). In our richest visions of democracy, democratic citizens would understand that voting is only a small part of their responsibilities and that democracy is always unfinished and thus needs our sustained attention; it is not a gift we have simply received from our ancestors. Neumann ( 2008 ) captures this expansive and rich vision of democracy well, maintaining that democratic citizenship “involves a disposition for social responsibility and civic engagement; it involves participation in groups concerned with advancing foundational principles of liberty, justice, and equality and with improving human welfare and the environment of the country and planet” (p. 332). That is, it requires critical thinking and the habit of working with others to deliberate on matters of social importance as well as “faith in the individual and collective capacity of people to create possibilities for resolving problems” (Beane & Apple, 2007 , p. 7). While this vision of democracy as a way of life may never have been actualized widely, it is currently under significant threat, especially by shallow yet increasingly pervasive interpretations of democracy as nothing more than a system that protects and celebrates individual self-interests.

Democracy Under Threat

It is difficult to say whether democracy is more troubled now than any other time in our history. While some may argue that the deleterious impacts of neoliberal forms of globalization have led to a deeply problematic conflation of market freedom with democratic freedom and, in effect, have reduced our sense of democracy to little more than an empty slogan, there has been no time in our history when we have fully lived up to our democratic ideals. Moreover, different versions of democracy have always been in tension. Advocates of liberal, individualistic approaches to democracy have typically elevated individual freedoms and rights above common goods, arguing that these goods themselves are always contested and that the best way to protect individual liberty is through minimal state intervention. While we proclaim in the U.S. Declaration of Independence the equality of all “men” and their inalienable rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, we have always excluded large groups of people from this supposed equality. It has taken the deliberate and sustained work of numerous civil rights activists to overturn slavery, extend voting privileges, and remove structural barriers to opportunity for historically marginalized peoples. And yet there is still much work to do to better achieve democracy in our times, especially given the growing gaps between the wealthy and poor around the world in terms of income, opportunity, health care, and overall quality of life. Indeed, advocates of more leftist visions of democracy suggest that we have lost sight of the fundamental commitment to equality that is part of democracy and maintain that states have an obligation to ensure not just “formal equality” among citizens “before the law, but also that citizens would have the actual capacity (and health, education, skills and resources) to take advantage of opportunities before them” (Held, 2006 , p. 278). They worry that we have frequently forgotten that democracy takes ongoing effort and commitment. Addressing this concern, Barber ( 1993 ) asserts that “we have been nominally democratic for so long that we presume it is our natural condition rather than the product of persistent effort and tenacious responsibility” (p. 44). He adds that “democracy is anything but a ‘natural’ form of association. It is an extraordinary and rare contrivance of cultivated imagination” (p. 44). As such, we need to perpetually attend to the work that democracy entails, recognizing that citizenship is an action, not merely a static identity.

Dewey also recognized the tendency to assume the existence of democracy rather than to understand it as an ongoing effort. He was especially troubled by this laissez-faire understanding while the United States was at the same time justifying its involvement in world wars “with the virtually unassailable statement that our soldiers were fighting to ‘make the world safe for democracy’ ” (Beane & Apple, 2007 , p. 5). Writing about the challenges he saw to our democratic way of life between the First and Second World Wars, Dewey ( 1938 ) called attention to our complacency and our habit of seeing democracy as simply a fact rather than a project that requires sustained focus. He lamented that citizens “had, without formulating it, a conception of democracy as something that is like an inheritance that can be bequeathed, a kind of lump sum that we could live off and upon” (pp. 298–299). Alternatively, he argued that each generation has to rework democracy in a fashion that is relevant for their times and that is responsive to contemporary challenges. Yet many people today still think of democracy in static ways, as a given, something that requires very little of citizens beyond voting and abiding by certain procedures. Goodlad, Mantle-Bromley, and Goodlad ( 2004 ) echo Dewey’s concern about stagnation, worrying that too many people simply “assume that the United States has a democratic system of governance” that was created “by the framers of the U.S. Constitution” and “that it is so thoroughly embedded in our collective psyche that it is invulnerable to external threats … and that all we have to do to maintain it is occasionally to vote” (p. 35). Compounding the belief that we have already fulfilled the promise of democracy in this country, the idea is also threatened by ambiguity surrounding its meaning, allowing it to be co-opted by those seeking to justify the global expansion of a way of life marked by self-interested, capitalist accumulation.

Absent sustained attention to the moral heart of democracy, namely commitment to individual freedom amid a concern for common goods, it often is reduced in public discourse and imagination to little more than a theory of individualism. We conflate capitalism and democracy, believing that an unregulated economic market is necessary and sufficient to secure democratic freedoms, which themselves are often reduced to consumer choices. Price ( 2011 ) argues that democracy is presented to us as system of governance that we ought to uncritically appreciate, one “that can only be built upon and sustained by free markets, private property, increased consumption and productivity, and the over-arching pursuit of profit” (p. 293). Yet unregulated capitalism under the guise of democratic globalization has led to the rapid concentration of wealth in the hands of an increasingly small portion of the population, as well as the pervasive assumption that economic growth inherently trickles down to the poor and improves their quality of life. There is little evidence that this is actually the case, and instead we have ever-growing gaps worldwide between the extremely wealthy and everyone else. One of the biggest challenges to democracy is the belief that our current approaches to globalization are actually democratic and that unregulated corporate behaviors can somehow protect the interests of citizens as opposed to simply shareholders.

Perhaps the biggest threat to democracy in our times is complacency. If we consider democracy as a given, we are unlikely to engage in the sustained efforts needed to bring it to fruition. Yet schools too often teach, both explicitly and implicitly, that democracy is merely the political system that we use to make decisions by in our country. We rarely discuss deeper visions for democracy or tensions and paradoxes within democracy or even reflect on the meaning of democracy at all. This allows those with more self-interested goals to assert, often persuasively, that their agendas are actually democratic. Apple and Beane ( 2007 ) capture this worry well when they argue that “rather than referring to ways in which political and institutional life are shaped by equitable, active, widespread, and fully informed participation, democracy is increasingly being defined as unregulated business maneuvers in a free-market economy” (p. 150). Revisiting the historic relationship between democracy and education can help to disrupt this reductive vision and provide the foundation needed to reclaim a more expansive understanding of what it means to live in a democratic society.

Historical Perspective on Democracy and Education

The founding and development of public schools in the United States were historically closely tied to democratic ideals. Indeed, as Schlesinger ( 2009 ) maintains, “it seems bizarre to have to make the case that the public school system should prepare citizens for democracy” (p. 88) since this why our school system was initially created in the first place. The founding fathers of the United States held important political motives for education, believing that critical literacy, as well as an understanding of history, were imperative for self-governance. These motives are evident in George Washington’s first message to Congress, where “he advocated for public schools that would teach students to ‘value their own rights’ and ‘to distinguish between oppression and the necessary exercise of lawful authority’” (Rothstein & Jacobsen, 2006 , p. 267). Consistently, in his farewell address he also talked about the importance of education to informed decision-making, claiming that “‘it is essential that public opinion should be enlightened’ by schools that teach virtue and morality” (Rothstein & Jacobsen, 2006 , p. 267).