The Yale Wave

In absentia lucis, tenebrae vincunt..

The Advantages of Being Bilingual

Language is one of the defining characteristics of humans. It is an interplay between culture, geography, and biology and is the one thing capable of connecting billions of people. At the time of writing, there are over 6,000 languages spoken across the globe, with English, Mandarin, Hindu, and Spanish being among the most widely spoken .

With such a massive diversity in spoken languages, it quickly becomes apparent why speaking multiple languages can be so advantageous. Geopolitics, education, and businesses rely heavily on efficient communication and minimal instances of misunderstandings. Think of how often simple linguistic misunderstandings cause large disputes and errors, both at the individual and collective level, and you can see why being bilingual is crucial for social activities. Below are some of the advantages of being bilingual

Communication is the key to understanding

One of the best advantages of being bilingual is that it will open up a new avenue for creating connections with others. The United States, for example, is home to 350 languages alone. As a result, it is seen as a melting pot for cultures, but unfortunately, tensions can arise within the country’s smaller communities simply due to language barriers. Having a sizable portion of the population fluent in at least one other language creates bridges between these communities, leading to fewer points of contention.

Teachers are some of the people best positioned to take on the task of fostering new generations of bilingual students. Schools across the U.S. already have foreign language courses integrated into their graduation requirements, but continued education in language studies is often recommended to obtain fluency. For those who never took a foreign language course in school or who wish to piggyback on what they’ve already learned, an online language tutor is arguably the best method toward fluency. There is also an assortment of self-paced online courses and smartphone apps that can supplement this knowledge.

Seeing as English is the most widely spoken language globally, it’s no surprise that it is rigorously instilled into students living in countries outside of the U.S. Learning English gives these students highly sought-after career opportunities in tourism and work abroad. That said, fluent English speakers also have a chance to make money teaching English to students who live in countries where English is not the native language.

Many companies often emphasize hiring people who are fluent in other languages. Knowing multiple languages will increase your odds of being hired, particularly in customer-facing roles. To tap into additional markets, hiring bilingual employees is strategic for businesses to have workers that can communicate with non-native language speaking demographics.

As a traveler, learning the language of the countries you visit opens up a more comprehensive lens into the culture, which has many benefits. For instance, learning Spanish and traveling across Latin America will give you a window into the deeper nuances of specific subcultures. It’ll also make it easier to navigate these countries, lessen the chances of falling for scams, allow getting better deals on consumer goods, and make befriending the locals easier.

All of this is to say that there is a clear incentive for bilingualism among different cultures to bypass language barriers and create a more interconnected, global society.

Exercising your mental faculties

Beyond the unifying nature of language, becoming bilingual has proven cognitive benefits for those who take on the effort. These benefits can be subtle, but ultimately bilingualism can make you a better reader, problem-solver, and general learner.

Whether or not you learned a second language as a child or later in life, studies have shown that being bilingual can help stave off cognitive decline in old age. What’s more, knowing how to switch between two languages has been shown to increase memory and creativity.

Having the ability to read in another language gives bilingual people access to more knowledge resources. For example, novels, news reports, and scientific studies written in another language are now accessible to bilingual people. In addition, increased use of these language skills is continually honed as new words and semantic nuances are discovered within these texts. And in terms of reading news reports, bilingual people can glean more profound insight into events happening across the world, thus making them more worldly people.

And finally, having already mastered another language, especially as a child, gives bilingual people the advantage of learning other skills. Language is a set of systems, much like any other system such as computing languages, scientific disciplines, and music.

So, not only does being bilingual increase your career opportunities, but it also grants learners cognitive abilities that can be applied to just about any other task that living in modern society requires. Moreover, by fostering bilingualism in as many people as possible, the world can become a much more unified and productive place to thrive within.

119 Bilingualism Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

🏆 best bilingualism topic ideas & essay examples, 👍 good essay topics on bilingualism, 🥇 most interesting bilingualism topics to write about, ✅ simple & easy bilingualism essay titles, ❓ questions about bilingualism.

- Bilingualism and Multilingualism However, to discuss the aspects of bilingualism and multilingualism, it is necessary to focus on the factor of the social motivation and psychological peculiarities of the ability to use two or more languages for interactions.

- Bilingualism and Multiculturalism Knowledge of languages contributes to the development of flexibility of thinking, attention, and a clearer understanding of the difference of cultures.

- Bilingual Education: Pros and Cons In this system, English is a secondary language geared to making students catch up with their academics until they can get comfortable enough to join mainstream English classes.’Bilingual education is a step backward in our […]

- Bilingualism and Approach to Second Language Acquisition Bilingualism has advantages, such as enriched cognitive control, that outweigh its disadvantages, increasing the importance of the communicative approach for second language acquisition that considers the Sapir-Whorf theory.

- Bilingual Neurodivergent Students If the child is raised in a bilingual family and the family language differs from the language spoken in society and at school, the problem may appear to be worsened.

- The Way Bilingual People Perceive Their Cultural Heritage Amy Tan writes in her essay “Mother’s tong” about the memories of her childhood, the inability of her mother to speak English as if it was her native language, and the ways it influenced the […]

- Employee Management: Bilingualism in Organizations Title VII has helped to decrease discrimination in the workplace. Prior to the introduction of the Title VII Act, employers denied women health benefits and incentives during leaves.

- Identifying Language Impairment in Bilingual Children Perhaps, the integration of more items from the Spanish language can equalize the informativeness of the two versions of the assessment tool.

- Bilinguals’ Cognitive-Linguistic Abilities and Alzheimer’s Disease This irregularity is reflected in the preserved linguistic abilities, including code-switching and semantic fluency, and the declined functions in translation, picture naming, and phonemic fluency, calling for improved therapy and testing practices.

- Language Ability Barriers in Bilingual Children Thus, the potential barriers to language ability assessment are the lack of adjustable tests with norms for various bilingual variations and the absence of specific criteria for language acquisition evaluation.

- Bilingual Training Program Interventions Furthermore, the author suggests that language development in bilingual children can progress in both types of training programs, but the use of bilingual programs enables the component of supportive context in family support.

- Language Switching in Bilingual Older Adults Bilingualism and multilingualism have been analyzed in terms of the peculiarities of bilinguals’ cognition and perception, as well as language processing, cognitive and perception differences between bilingual and monolingual people, and the characteristics of bilingualism […]

- Bilingual and Immersive Educational Strategies The multinational diversity contained in the territories of the States requires the introduction of the study of several languages in the practice of teaching children.

- Native Language Loss in Bilinguals The present research aims to analyze the process of native language loss, in particular, the age when bilinguals cease to use their language and when they start to forget it.

- The Effect of Childhood Bilingualism on Episodic and Semantic One of the main points of the study work is to implement memory tasks similar in advantage and thematic background for two groups of children living in a multinational society.

- Language Development and Bilingualism in Children Prior to acquiring particular words and phrases, the child must show signs of willingness to interact with another person, which is a leading trait of this phenomenon.

- Bilingual and Immersion Methods of Learning English It was previously believed in the scientific discourse that learning English is best done in the process of immersion in the language environment.

- Bilingualism and Communication: Motivation, Soft Skills and Leadership This essay will focus on the effects of learning a foreign language on communication competency, specifically interpersonal, cultural, and leadership skills. Firstly, one of the essential effects of learning a new language is an increase […]

- Bilingualism Resistance and Receptivity Explained This paper will also seek to explain how social psychology has been a factor in influencing the reception and resistance to bilingualism. This paper has discussed how literacy is vital in determining the resistance or […]

- “Viva Bilingualism” by James Fallows In his article Viva Bilingualism, James Fallows analyzes such issue as bilingualism in the United States, in particular, the author argues that two or even more languages can successfully co-exist in America and it will […]

- History of Singaporean Education: Independence and Bilingualism in Schools The government increased budgetary allocation to the education and primary education received 59% of the budget allocation, whereas 27% and 14% of the budget allocation went to secondary school and higher education respectively.

- Bilingual Education: Benefit in Today’s World In most cases, the language is a part of any culture in the world, and preventing bilingual education can have a negative effect on many cultures in the United States.

- Bilingualism and English Only Laws According to, laws that require English to be the only official language that should be in U. However, supporters of laws that require English to be the only language that should be used in U.

- Bilingual Education: Enhancing Teachers Quality More so, the number of English language learners in the urban classes is increasing in such a rate that the number of bilingual teachers has to be increased in ten fold.

- Bilingualism: Views of Language The degree of development of speech inevitably affects feeling of the child when skill to state the ideas and to understand speech of associates influences their place and a role in a society.

- Bilingualism in Professional Life The importance of bilingualism at the professional level is displayed through the changes in society as a whole and the advantages that are speaking two languages has.

- English Vocabulary Acquisition in Bilingual Students The principal emphasis is put on the lexical side of the language; thus, the researchers carry out a detailed analysis of the vocabulary units that the students employ.

- Why Bilinguals Are Smarter? The tasks have led to the assertion that bilingualism has an effect on the brain that leads to improvement of the cognitive skills that are not related to language.

- Bilingual Education Impact on Preschoolers The key questions to be addressed in the literature review are concerned with the understanding of children’s early development in relation to bilingual education: Is dual-language learning beneficial or disadvantageous for small children?

- Bilingualism as a National Language Policy The use of the language in formal learning and communication is the key determinant of the importance and effectiveness of a language.

- Parents Challenges: Raising Bilingual Children The problem is significant due to the lack of parents’ knowledge about the importance of language development and the absence of efforts on the part of educators with regards to teaching bilingual children.

- Bilingual and ESL Programs Implementation in Schools As for ESL pull-out programs, they are based on pulling minority students out of the mainstream classroom to provide them with class instruction in English as a second language.

- Bilingual Education for Minority Language Students in the US According to Kim, the aim of the research is to underline the significance of the bilingual approach and determine the trends in this field in American society.

- Bilingual Education Concept One of the reasons as to why there is opposition to bilingual education is the fact that students tend to greatly rely on their native language, keeping them from learning as well as having proficiency […]

- Linguistics: Bilingualism, Multilingualism and Tolerance In my opinion, a person with some understanding of a local language is likely to find some of the social and cultural things in a foreign country awkward or abnormal.

- Education: Bilingual Kindergarten A major problem with bilingualism in kindergartens is that it leads to a lack of mastery in either of the languages.

- The Peculiarities of the Bilingual Education The peculiarities of the bilingual situation in the context of Melbourne, Victoria, with focusing on the usage of the Italian language In relation to the question of using one or more languages, Australia can be […]

- “Translanguaging in the Bilingual Classroom: A Pedagogy for Learning and Teaching” Among the benefits of flexible pedagogy and flexible bilingualism identified by the authors are ease of communication and preservation of culture, indiscrimination of a second language and simultaneous ‘literacies’ endorsement as students participating in bilingual […]

- Benefits of Bilingualism Among Kindergarten Children The purpose of this report is to show the benefits of learning more than one language among kindergarten children. The purpose of this report is to analyse the benefits of learning two languages among kindergarten […]

- Bilingual Education: Programmes in Australia In this situation, the English language is the primary language in Australia, and the other languages are discussed as the languages of minorities.

- Paweł Zielinski’s Report on Bilingualism This text aims to find the correct definition of the term ‘bilingual’, by identifying the characteristics that define a bilingual, the distinctions caused by the different times a language is learned, and whether learning a […]

- The Benefits and Issues in Bilingual Education Understanding the term ‘bilingual education’ as a simple educational process would be a mistake because in reality it denotes a complex phenomenon dependent upon a set of variables, including the learners’ native language and the […]

- Bilingualism and the Process of Language Acquisition: Speeding up Cognition and Education Processes When it comes to mentioning the positive aspects of being a bilingual person, the first and the foremost advantage to mention is the ability to convey specific ideas in either of the languages without any […]

- Bilingualism in East Asia Countries In most East Asian countries, multilingualism is restricted to elites; although patterns of language ability differ between the classes multilingualism is the norm at all levels of the society.

- Bilingualism in Canada However, the code-switching of language words between English and French have raised concerns of the French standard in Canada, particularly in Quebec. The effectiveness of French speaking programs in Canada is unknown.

- Sociolinguistics: Bilingualism and Education This means that children are forced to acquire the language of majority to be treated in accordance with the same rules and traditions applicable to the monolingual majority.

- Bilingual Development: Second Language Acquisition Successive acquisition is similar to first language acquisition because a child learns the second language through analysis of rules and making errors.

- The Benefits of Being Bilingual in a Global Society And, it represents the matter of crucial importance for educators to be able to adopt a proper perspective onto the very essence of bilingualism/multilingualism, as it will increase their ability to design teaching strategies in […]

- Why Is Bilingual Education Important Considering the diversity nature of students in any classroom scenario, it is important for the teaching orientation to adopt a variety of mechanisms, which will ensure there is satisfaction of all learner needs.

- Bilingualism Affects Audio-Visual Phoneme Identification

- Role of Bilingualism and Biculturalism as Assets in Positive Psychology

- The Intellectual Power of Bilingualism

- Bilingualism Impact on Intelligence and Scholastic Achievement

- Why Bilingual Education Is Even More Relevant Today

- The Benefits of Raising a Bilingual Child With Autism

- Perspectives on Bilingualism and Bilingual Education for Deaf Learners

- Bilingualism in the Education of Adolescents

- The Roots of Bilingualism in Newborns

- Advantages of Bilingualism and Multilingualism

- The Cognitive Benefits of Bilingualism in Autism Spectrum Disorder

- The Bilingual Brain: Language, Culture, and Identity

- Are the Cognitive Benefits of Bilingualism Restricted to Language

- Bilingualism and Its Importance in Education

- Executive Function and Bilingualism in Young and Older Adults

- Benefits of Bilingualism in Early Childhood

- Audio-Visual Integration During Bilingual Language Processing

- Economic Advantages of Bilingualism

- Myths & Facts About Bilingual Children

- The Impact of Bilingualism on Cognitive Development

- Bilingualism and Bilingual Education as a Problem Right and Resource

- Parents’ Attitudes Towards Bilingualism and Bilingual Education

- Structural Brain Changes Related to Bilingualism

- The Effects of Bilingualism on Language Development of Children

- Bilingual Benefits Reach Beyond Communication

- Teacher Candidates’ Beliefs About and Knowledge of Bilingualism and Bilingual Education

- Childhood Second Language Learning and Subtractive Bilingualism

- The Effect of Bilingualism and Age on the Subcomponents of Attention

- How Bilingualism Can Affect the Way Individuals Interact

- Foreign Language Acquisition, Bilingualism, and Biculturalism

- The Influence of Bilingualism on Third Language Acquisition

- What Are the Advantages and Disadvantages of Bilingualism

- Bilingualism and Its Impact on the Development of the World

- Why Bilingual Students Have a Cognitive Advantage for Learning to Read

- Do Bilinguals Have Better Cognitive Control

- Language Lateralization in Adult Bilinguals

- Flexibility in Task Switching by Monolinguals and Bilinguals

- Assessing the Double Phonemic Representation in Bilingual Speakers of Spanish and English

- Benefits of Bilingualism: Why Is Bilingual Education Important

- Bilingual Education Helps to Improve the Intelligence of Children

- Is Bilingualism Important in Today’s Generation?

- How Does Bilingualism Impact an English Language Learner?

- Does Bilingualism Improve Brain Functioning?

- Why Do the Effects of Bilingualism Change Language Acquisition?

- How Can Bilingualism Have a Positive Impact on a Country?

- What Is the Importance of Bilingualism in Globalization?

- How Does Bilingualism Affect the Learning Process of Children?

- Is Bilingualism Growing in the US?

- How Does Bilingualism Increase Brain Power?

- What Factors Influence the Development of Bilingualism?

- Does Bilingualism Among the Native Born Pay?

- How Can Bilingualism Affect Cognitive Functions?

- Why Is Bilingualism Important in the US?

- How Does Bilingualism Improve Your Health?

- What Are the Advantages of Early Bilingualism?

- Does Bilingualism Improve Social Life?

- How Does Bilingualism Affect Society?

- What Are the Benefits of Bilingual Education to the Society?

- Does Bilingualism Affect Cognitive Development?

- How Does Bilingualism Help the Economy?

- Does Bilingualism Affect Culture?

- What Are the Challenges of Bilingualism?

- How Does Bilingualism Impact Language Development?

- What Is the Relationship Between Bilingualism and Cognition?

- How Is Bilingualism Good for a Country?

- Teaching Philosophy Research Topics

- Homeschooling Ideas

- Private School Research Ideas

- Social Development Essay Topics

- Distance Education Topics

- Classroom Management Essay Topics

- Online Education Topics

- Grammar Topics

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, March 2). 119 Bilingualism Essay Topic Ideas & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/bilingualism-essay-topics/

"119 Bilingualism Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." IvyPanda , 2 Mar. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/bilingualism-essay-topics/.

IvyPanda . (2024) '119 Bilingualism Essay Topic Ideas & Examples'. 2 March.

IvyPanda . 2024. "119 Bilingualism Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." March 2, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/bilingualism-essay-topics/.

1. IvyPanda . "119 Bilingualism Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." March 2, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/bilingualism-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "119 Bilingualism Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." March 2, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/bilingualism-essay-topics/.

- Communication

- Interpretation

- Interpreting

- Translation

The Importance of Being Bilingual: A Key to Success in a Globalized World

In today’s interconnected and multicultural world, the importance of being bilingual cannot be overstated. With more than half of the global population speaking at least two languages, the ability to communicate across linguistic boundaries is not just a beneficial skill—it is a transformative asset. As a company specializing in translation, localization, and interpretation services, we understand the profound impact that bilingualism can have on personal and professional lives.

Cross-Cultural Communication and Cognitive Benefits

Why being bilingual is important begins with its unparalleled ability to bridge cultures. Being fluent in more than one language opens doors to different traditions, customs, and perspectives, fostering a global mindset. This cultural fluency is invaluable in an era where businesses and individuals increasingly engage across borders. Beyond enhancing communication, bilingualism significantly impacts cognitive abilities. Studies have shown that bilingual individuals excel in attention control, problem-solving, and multitasking. The bilingual brain is adept at switching between languages, which enhances cognitive flexibility and creativity.

Educational and Professional Advantages

Another critical aspect of why being bilingual is important is its impact on education and career prospects. Bilingual children often outperform their monolingual peers academically, showing greater focus and problem-solving abilities. This cognitive edge continues into adulthood, providing significant advantages in the job market. As businesses expand globally, the demand for bilingual employees grows. Companies value individuals who can navigate diverse cultural landscapes, making bilingualism a sought-after skill in international business, healthcare, and technology.

Health and Social Benefits

The benefits of being bilingual extend beyond intellectual and professional realms. Research indicates that bilingualism can delay the onset of dementia and Alzheimer’s, promote faster recovery from strokes, and lower stress levels. Socially, bilingual individuals can connect with a wider range of people, enhancing their ability to build relationships across cultures. This adaptability and open-mindedness enrich personal lives and professional interactions, making bilingual individuals more resilient and versatile.

The Future of Bilingualism

As we move further into a multicultural and multilingual world, the necessity of bilingualism becomes increasingly apparent. Being bilingual is not just a skill for personal enrichment but a critical component of professional success and global citizenship. The ability to communicate in multiple languages enriches travel experiences, fosters social connections, and enhances one’s overall quality of life.

At Dynamic Language, we believe in the transformative power of bilingualism. Whether you want to expand your business internationally, improve cross-cultural communication, or simply understand why being bilingual is important , our team of experts is here to help. We offer comprehensive translation, localization, and interpretation services tailored to your needs. Take advantage of the opportunities that bilingualism can bring. Contact us today to learn more about how we can assist you in navigating a multilingual world. Together, let’s unlock the full potential of being bilingual.

FAQ: The Benefits and Importance of Being Bilingual

What are 5 benefits of being bilingual.

- Cognitive Enhancement: Bilingual individuals often have improved multitasking, problem-solving skills, and cognitive flexibility due to constantly switching between languages.

- Cultural Awareness: Bilingualism opens doors to understanding and appreciating different cultures, traditions, and perspectives, fostering a global outlook.

- Career Opportunities: Being bilingual enhances job prospects and earning potential, as many companies prioritize candidates who can communicate in multiple languages.

- Health Benefits: Studies show that bilingualism can delay the onset of dementia and Alzheimer’s and aid in faster stroke recovery.

- Improved Social Skills: Bilingual individuals can connect with a wider range of people, enhancing social interactions and relationships.

What is the importance of bilingualism?

Bilingualism is crucial in today’s globalized world as it facilitates cross-cultural communication, fosters better understanding between diverse groups, and enhances cognitive abilities. It provides individuals with a competitive edge in the job market, as companies increasingly operate internationally and require employees who can communicate effectively in different languages. Additionally, bilingualism contributes to personal growth by broadening one’s perspective and deepening cultural appreciation.

Why are bilingual skills important?

Bilingual skills are important because they enable effective communication across language barriers, which is essential in business, travel, and daily life. They enhance cognitive functions such as attention and task-switching, making individuals better problem-solvers and multitaskers. In professional settings, bilingual skills are highly valued as they allow for better engagement with international clients and partners, increasing an individual’s employability and potential for career advancement.

Is being bilingual worth it?

Absolutely, being bilingual is worth it. The benefits extend beyond communication and cognitive advantages, including improved career prospects, enhanced travel experiences, and a deeper understanding of different cultures. The cognitive benefits, such as better problem-solving and multitasking abilities, alongside the potential for delayed cognitive decline in old age, make bilingualism a valuable skill. Furthermore, the ability to connect with a broader range of people and cultures enriches personal and professional life, making the effort to become bilingual well worth it.

How does being bilingual affect you?

Being bilingual positively affects individuals in numerous ways. It enhances cognitive functions like memory, creativity, and multitasking abilities. It also fosters cultural sensitivity and empathy, allowing individuals to navigate and appreciate different cultural contexts more effectively. Professionally, bilingual individuals often have better job prospects and higher earning potential. On a personal level, being bilingual can improve social interactions and relationships, as it allows for communication with a broader range of people. Additionally, research suggests bilingualism can have long-term health benefits, such as delaying cognitive decline and reducing stress.

Why AI Matters in eLearning Localization: How the Right Language Services Provider Can Use AI to Benefit You

As eLearning continues to evolve, the demand for high-quality, localized…

You might also be interested in

The Impact of AI in Higher…

As higher education continues to expand, institutions are…

Is Your Language Services Provider Meeting…

Picture it: you’re a higher education institution that…

Reasons Why Responsiveness Matters for eLearning…

How do you deliver content that resonates across…

15215 52nd Avenue S., Suite 100 Seattle, WA 98188-2354 [email protected] 206.244.6709 Toll-free: 800.682.8242

- Transcreation

- Transcription

- Subtitling & Voice Over

- Additional Services

- Localization

- Technology (IT/Product)

- Documentation

- Translate a File

- Interpret a Meeting

- Transcribe a Recording

- Automate Processes

- Translate a Video

- Other Industries

- Case studies

- White papers

- Privacy policy

Copyright 2024 © Dynamic Language. All rights reserved.

Home — Essay Samples — Science — Bilingualism — The Importance of Being Bilingual in a Globalized World

The Importance of Being Bilingual in a Globalized World

- Categories: Bilingualism

About this sample

Words: 440 |

Published: Mar 6, 2024

Words: 440 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Table of contents

Cognitive benefits of bilingualism, professional opportunities for bilingual individuals, cultural understanding and empathy.

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof. Kifaru

Verified writer

- Expert in: Science

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

3 pages / 1139 words

4 pages / 1859 words

8 pages / 3804 words

1 pages / 660 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Bilingualism

In the past, people thought being bilingual was a problem for learning languages. Nowadays, though, it's seen as a big plus. Different folks have different takes on what being bilingual really means, but most agree that [...]

Advantages of speaking more than one language extend beyond simple communication; they encompass cognitive, educational, and cultural dimensions that enrich individuals' lives. Multilingualism, the ability to converse in [...]

Bilingual education is an approach to learning that involves the use of two languages, typically the student's native language and a second language. This approach has been gaining popularity in recent years, as educators and [...]

Bilingual education has been a hot topic in the U.S. for a long time. Richard Rodriguez, in his book "Hunger of Memory: The Education of Richard Rodriguez," shares a pretty controversial view on this subject. In this essay, I'll [...]

Bilingualism offers a unique perspective on language acquisition and cognitive development, challenging conventional notions of language proficiency and highlighting the benefits that come with mastering multiple languages. This [...]

Studies that involve bilingual acquisition studies highlight the frequency of perception in which language one is stable while language two is compelling because it experiences changes in development. These studies question [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Essay on Bilingualism

Students are often asked to write an essay on Bilingualism in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Bilingualism

What is bilingualism.

Bilingualism is when a person can speak two languages. This skill can be gained early in life, like a child growing up in a house where two languages are spoken. It can also be learned later, like a student studying a second language in school.

Benefits of Bilingualism

Being bilingual has many good points. It can make your brain stronger and more flexible. It can also make it easier to understand and learn about other cultures. Plus, being able to speak two languages can help you get jobs in the future.

Challenges of Bilingualism

Learning two languages can be hard. It takes time and practice. Sometimes, people who speak two languages can mix them up. But with patience and hard work, these challenges can be overcome.

Bilingualism in Society

In many places around the world, being bilingual is normal. In these places, people use two languages to live, work, and play. This shows how important and useful bilingualism can be in our lives.

250 Words Essay on Bilingualism

Bilingualism is a term used when a person can speak two languages fluently. This skill is often gained when a person is brought up in a family or a place where two languages are spoken regularly.

Benefits of Being Bilingual

Being bilingual has many benefits. It makes the brain strong and flexible. This is because switching between two languages is a mental workout for the brain. It also helps in connecting with different people and understanding different cultures.

Challenges in Bilingualism

Learning two languages can be hard. It takes time and practice to become fluent in two languages. Sometimes, it can also be confusing to switch between languages.

How to Become Bilingual?

To become bilingual, one can start learning a new language at a young age. Schools, online courses, and language clubs offer classes. Practicing speaking, reading, and writing in the new language every day can also help.

Bilingualism is a valuable skill. It helps in brain development, understanding cultures, and connecting with people. Though it can be challenging, with regular practice, anyone can become bilingual.

500 Words Essay on Bilingualism

Bilingualism is a term that describes a person’s ability to speak two languages. It’s like having two tools in your toolbox instead of one. When a person can speak, read, and write in two languages, we say that person is bilingual. Some people learn two languages when they are very young, maybe because their parents speak different languages. Others learn a second language at school or as an adult.

Being bilingual has many benefits. It’s not just about being able to talk to more people. It can also help your brain. Scientists have found that bilingual people often do better at tasks that need multitasking. This is because using two languages often means you are better at switching between different tasks.

Bilingual people can also find it easier to learn more languages. If you already know two languages, picking up a third or even a fourth can be easier. This is because you already understand how languages work.

Bilingualism and Culture

Language is a big part of culture. By learning and understanding another language, you can also learn about another culture. This can make you more open-minded and understanding of people who are different from you. It can also help you feel connected to more people around the world.

While knowing two languages can be great, it can also be hard. Sometimes, bilingual people can get confused between the two languages. They might mix up words or use the wrong grammar. This is called “code-switching”. It’s normal and usually not a big problem. But it can be frustrating.

Also, if you don’t use one of your languages often, you might forget some of it. This is why it’s important to practice both languages regularly.

In conclusion, being bilingual can be a great skill. It can help your brain, make it easier to learn more languages, and help you understand other cultures. But it can also be hard and require a lot of practice. Whether you’re born into a bilingual family or decide to learn a second language, it’s a journey that can open up a world of opportunities.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Hobby Reading

- Essay on Hobby Painting

- Essay on Big Bang Theory

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Gray Matter

Why Bilinguals Are Smarter

By Yudhijit Bhattacharjee

- March 17, 2012

Editor’s Note: We’re resurfacing this story from the archives to show you how learning a second language can improve how you think.

SPEAKING two languages rather than just one has obvious practical benefits in an increasingly globalized world. But in recent years, scientists have begun to show that the advantages of bilingualism are even more fundamental than being able to converse with a wider range of people. Being bilingual, it turns out, makes you smarter. It can have a profound effect on your brain, improving cognitive skills not related to language and even shielding against dementia in old age.

This view of bilingualism is remarkably different from the understanding of bilingualism through much of the 20th century. Researchers, educators and policy makers long considered a second language to be an interference, cognitively speaking, that hindered a child’s academic and intellectual development.

They were not wrong about the interference: there is ample evidence that in a bilingual’s brain both language systems are active even when he is using only one language, thus creating situations in which one system obstructs the other. But this interference, researchers are finding out, isn’t so much a handicap as a blessing in disguise. It forces the brain to resolve internal conflict, giving the mind a workout that strengthens its cognitive muscles.

Bilinguals, for instance, seem to be more adept than monolinguals at solving certain kinds of mental puzzles. In a 2004 study by the psychologists Ellen Bialystok and Michelle Martin-Rhee, bilingual and monolingual preschoolers were asked to sort blue circles and red squares presented on a computer screen into two digital bins — one marked with a blue square and the other marked with a red circle.

In the first task, the children had to sort the shapes by color, placing blue circles in the bin marked with the blue square and red squares in the bin marked with the red circle. Both groups did this with comparable ease. Next, the children were asked to sort by shape, which was more challenging because it required placing the images in a bin marked with a conflicting color. The bilinguals were quicker at performing this task.

The collective evidence from a number of such studies suggests that the bilingual experience improves the brain’s so-called executive function — a command system that directs the attention processes that we use for planning, solving problems and performing various other mentally demanding tasks. These processes include ignoring distractions to stay focused, switching attention willfully from one thing to another and holding information in mind — like remembering a sequence of directions while driving.

Why does the tussle between two simultaneously active language systems improve these aspects of cognition? Until recently, researchers thought the bilingual advantage stemmed primarily from an ability for inhibition that was honed by the exercise of suppressing one language system: this suppression, it was thought, would help train the bilingual mind to ignore distractions in other contexts. But that explanation increasingly appears to be inadequate, since studies have shown that bilinguals perform better than monolinguals even at tasks that do not require inhibition, like threading a line through an ascending series of numbers scattered randomly on a page.

The key difference between bilinguals and monolinguals may be more basic: a heightened ability to monitor the environment. “Bilinguals have to switch languages quite often — you may talk to your father in one language and to your mother in another language,” says Albert Costa, a researcher at the University of Pompeu Fabra in Spain. “It requires keeping track of changes around you in the same way that we monitor our surroundings when driving.” In a study comparing German-Italian bilinguals with Italian monolinguals on monitoring tasks, Mr. Costa and his colleagues found that the bilingual subjects not only performed better, but they also did so with less activity in parts of the brain involved in monitoring, indicating that they were more efficient at it.

The bilingual experience appears to influence the brain from infancy to old age (and there is reason to believe that it may also apply to those who learn a second language later in life).

In a 2009 study led by Agnes Kovacs of the International School for Advanced Studies in Trieste, Italy, 7-month-old babies exposed to two languages from birth were compared with peers raised with one language. In an initial set of trials, the infants were presented with an audio cue and then shown a puppet on one side of a screen. Both infant groups learned to look at that side of the screen in anticipation of the puppet. But in a later set of trials, when the puppet began appearing on the opposite side of the screen, the babies exposed to a bilingual environment quickly learned to switch their anticipatory gaze in the new direction while the other babies did not.

Bilingualism’s effects also extend into the twilight years. In a recent study of 44 elderly Spanish-English bilinguals, scientists led by the neuropsychologist Tamar Gollan of the University of California, San Diego, found that individuals with a higher degree of bilingualism — measured through a comparative evaluation of proficiency in each language — were more resistant than others to the onset of dementia and other symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease: the higher the degree of bilingualism, the later the age of onset.

Nobody ever doubted the power of language. But who would have imagined that the words we hear and the sentences we speak might be leaving such a deep imprint?

The Gray Matter column on bilingualism last Sunday misspelled the name of a university in Spain. It is Pompeu Fabra, not Pompea Fabra.

When we learn of a mistake, we acknowledge it with a correction. If you spot an error, please let us know at [email protected] . Learn more

Yudhijit Bhattacharjee is a staff writer at Science.

Bilingualism as a Life Experience

- Posted October 1, 2015

- By Bari Walsh

What do we know about bilingualism? Much of what we once thought we knew — that speaking two languages is confusing for children, that it poses cognitive challenges best avoided — is now known to be inaccurate. Today, bilingualism is often seen as a brain-sharpening benefit, a condition that can protect and preserve cognitive function well into old age.

Indeed, the very notion of bilingualism is changing; language mastery is no longer seen as an either/or proposition, even though most schools still measure English proficiency as a binary “pass or fail” marker.

A growing body of evidence suggests that lifelong bilingualism is associated with the delayed diagnosis of dementia. But the impact of language experience on brain activity has not been well understood.

It turns out that there are many ways to be bilingual, according to HGSE Associate Professor Gigi Luk , who studies the lasting cognitive consequences of speaking multiple languages. “Bilingualism is a complex and multifaceted life experience,” she says; it’s an “interactional experience” that happens within — and in response to — a broader social context.

Usable Knowledge spoke with Luk about her research and its applications.

Bilingualism and executive function

As bilingual children toggle between two languages, they use cognitive resources beyond those required for simple language acquisition, Luk writes in a forthcoming edition of the Cambridge Encyclopedia of Child Development . Recent research has shown that bilingual children outperform monolingual children on tasks that tap into executive function — skills having to do with attention control, reasoning, and flexible problem solving.

Their strength in those tasks likely results from coping with and overcoming the demand of managing two languages. In a bilingual environment, children learn to recognize meaningful speech sounds that belong to two different languages but share similar concepts.

In a paper published earlier this year , she and her colleagues looked at how bilingualism affects verbal fluency — efficiency at retrieving words — in various stages of childhood and adulthood. In one measure of verbal acumen called letter fluency — the ability to list words that begin with the letter F, for instance — bilinguals enjoyed an advantage over monolinguals that began at age 10 and grew robust in adulthood.

Bilingualism and the aging brain

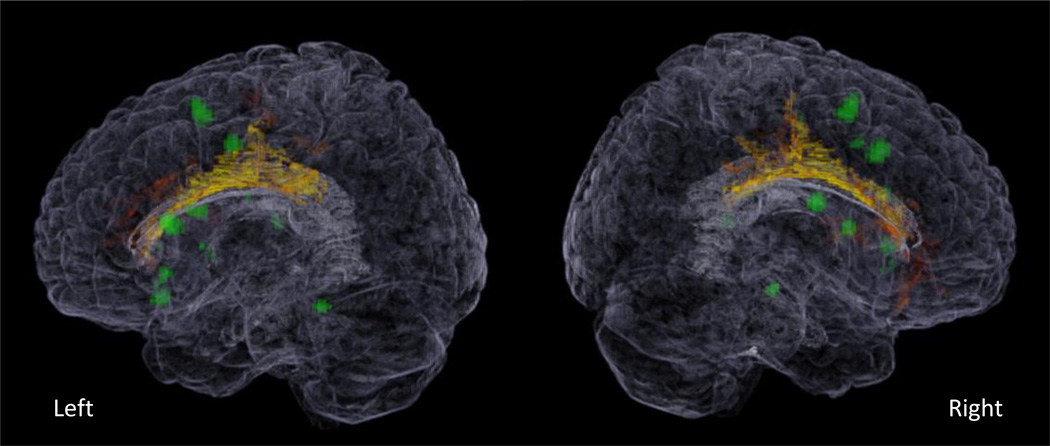

Luk and her researchers are looking at the neuroscience of bilingualism — at how bilingualism may affect the physical structure of the brain in its different regions.

What they’ve found so far shows that older adults who are lifelong bilinguals have more white matter in their frontal lobes (important to executive function) than monolinguals, and that their temporal lobes (important to language function) are better preserved. The results support other evidence that persistent bilingual experience shapes brain functions and structures.

A growing body of evidence suggests that lifelong bilingualism is associated with the delayed diagnosis of dementia. But the impact of language experience on brain activity is not well understood, Luk says.

In a 2015 paper, she and her colleagues began to look at functional brain networks in monolingual and bilingual older adults. Their findings support the idea that a language experience begun in childhood and continued throughout adulthood influences brain networks in ways that may provide benefits far later in life.

Who is bilingual?

Monolingualism and bilingualism are not static categories, Luk says, so the question of what it means to be bilingual, and who is bilingual, is nuanced. There are several pathways to bilingualism. A child can become bilingual when parents and caregivers speak both languages frequently, either switching between the two. A child can be bilingual when the language spoken at home differs from a community’s dominant language, which the child is exposed to in schools. Or a child can become bilingual when he or she speaks the community’s dominant language at home but attends an immersion program at school.

Bilingualism is an experience that accumulates and changes over time, in response to a child’s learning environments, says Luk.

Language diversity in schools

In one of her projects, Luk works with a group of ELL directors to help them understand the diverse needs of their language learners and to find better ways to engage their parents. She’s looking at effective ways to measure bilingualism in schools; at connections between the science of bilingualism and language and literacy outcomes; and at the long-term relationship between academic outcomes and the quality and quantity of bilingual experience in young children.

Part of her goal is to help schools move beyond binary categorizations like “ELL” and “English proficient” and to recognize that language diversity brings challenges but also long-term benefits.

“If we only look at ELL or English proficient, that’s not a representation of the whole spectrum of bilingualism,” she says. “To embrace bilingualism, rather than simply recognizing this phenomenon, we need to consider both the challenges and strengths of children with diverse language backgrounds. We cannot do this by only looking at English proficiency. Other information, such as home language background, will enrich our understanding of bilingual development and learning.”

Additional Resources

- A Boston community organization that runs a bilingual preschool spoke with Luk about her work and its applications to practice. Read the interview.

Usable Knowledge

Connecting education research to practice — with timely insights for educators, families, and communities

Related Articles

Fun and (Brain) Games

You Need /r/ /ee/ /d/ to Read

Fischer Commentary Featured in American Psychologist

Improve your Grades

Benefits of Being Bilingual Essay | Long and Short Essays on Benefits of Being Bilingual for Students and Children

October 01, 2021 by Prasanna

Benefits of Being Bilingual: Language evolution has taken place over the years in different parts of the world. Languages have changed and developed through social needs. To communicate with different groups for trade, travel, and other reasons people have started using more than one language. Many countries also have more than one official language. There are some prominent benefits of being bilingual as revealed through various research and analysis. Let’s discuss some of the cognitive benefits of being bilingual.

You can also find more Essay Writing articles on events, persons, sports, technology and many more.

Long Essay on Benefits of Being Bilingual

Develop Brain Power

Learning a second language other than a native language develops a person’s learning aptitude and helps in a great way to keep the brain alert and healthy. It can improve creativity, problem-solving skills, attention control, and confidence. Learning other languages from an early stage can help improve a child’s educational development, social and emotional skills that have positive effects for many years to come. It is also found that people who are conversant with more than one language can process information more efficiently and easily.

Improve Cultural Awareness

Being bilingual gives an individual an opportunity to get exposed to diverse cultures, ideas, and perspectives by way of learning and communication. The children who are born and brought up in different countries get to learn different languages besides the home language. The benefits of being bilingual can be seen in children as they acknowledge the value of other cultures and heritage.

Enhance Social Life

Knowing a second language gives the ability for more social interactions and enhances social skills. The benefits of being bilingual are to connect with a wider range of people; express and interact with more confidence in social situations. This skill often makes you more presentable and attractive while building meaningful relationships. Learning a country’s language when traveling to that country gives a more immersive and authentic experience. It would be easier to communicate with the local language and make more friends. Bilingual skills help individuals to adjust with others from varying cultures and backgrounds. Through this communication skill, one can be more perceptive of others, and be more empathetic.

Better Job Opportunities

One of the benefits of being bilingual is new career and job opportunities. Companies with international offices and client bases consider bilingualism an added advantage. Multilingual consumers constitute a major part of the commercial force and represent a significant opportunity for business. So there are demands for employees who can speak other languages and navigate different cultural expectations. Fields like travel and tourism, healthcare, journalism, and national security give priority to candidates with bilingual language skills.

Improve Learning Aptitude

Researchers established the fact that bilingual adults learn a third language better than monolingual adults. Learning a different language helps one to develop better attention and interest towards other languages in general. The improved understanding of how language works, coupled with the experience already gained, makes it all the easier to learn a third or fourth language. Bilingual experience may help to follow a new language more clearly leading to better learning. The benefits of being bilingual may be rooted in the ability to focus on information while reducing interference from the languages already known.

There are valuable benefits associated with the skill of being bilingual, be it individual or social. It gives the ability to explore a diverse culture, people, and customs. It is really fascinating to interact with someone with whom you might otherwise never be able to communicate. The behavioral changes and social advantages observed are major benefits of being bilingual. It highlights the need to consider how bilingualism shapes the activity and attitude of people in a positive manner.

Short Essay on Benefits of Being Bilingual

Introduction

Language evolution has taken place gradually with advancements of civilization and languages change and develop over time. Different groups of people would have found themselves speaking different languages due to social influence. Learning a second language expands a person’s social circle, improves confidence, and enables them to connect with a growing diverse population of the multilingual community.

Studies have found that being bilingual can improve the ability to focus attention and perform tasks effectively. Bilingual children become more successful in problem-solving and can have a creative approach. Learning a new language helps in a great way to keep the mind focused and sharp.

Bilingual skill can help to interact with different people and understand another culture including music, film, and literature. This means there are more opportunities to make friends, explore different hobbies, and improve social skills. Bilingual people tend to be more open to communication as they can interact through both languages.

Considering the benefits of being bilingual, the educational curriculums in many schools include a compulsory third language to be taught to children. There are private coaching facilities available also to provide learning on a second language. The knowledge of more than one language has several benefits in the long run because of diverse job opportunities. Being in a country without knowing the local language creates a lot of problems, whereas if you can communicate with that language it becomes more convenient to handle any situation. Even one can work as an interpreter to help others to communicate and get appreciation in return which is self-motivating.

Conclusion on Benefits of Being Bilingual

The benefits of being bilingual can be observed through the awareness and the ability to recognize language as a means of building connections and relationships. It brings confidence and motivation to one’s personality which is one of the most important benefits of being bilingual.

FAQ’s on Benefits of Being Bilingual

Question 1. What are the job opportunities for a bilingual person?

Answer: There are job opportunities in the travel and tourism industry, healthcare, Journalism, Teaching, MNCs, and Embassies, etc.

Question 2. Should a foreign language be a part of the educational curriculum for children?

Answer: Yes, learning a foreign language is very important at the school level so that students can capture it quickly and enhance their knowledge about other cultures and heritage.

Question 3. How does bilingualism help people traveling to another country?

Answer: Traveling becomes more convenient and enjoyable when there is no language barrier. With the knowledge of a foreign language, it becomes easier to process information about a new place.

Question 4. What percentages of people speak two languages across the world?

Answer: Around the world, nearly 60%-70% of people speak at least two languages.

Question 5. How do bilingual skills help to improve social life?

Answer: Being bilingual one can get exposed to other cultures and be able to interact in social surroundings building more relationships.

- Picture Dictionary

- English Speech

- English Slogans

- English Letter Writing

- English Essay Writing

- English Textbook Answers

- Types of Certificates

- ICSE Solutions

- Selina ICSE Solutions

- ML Aggarwal Solutions

- HSSLive Plus One

- HSSLive Plus Two

- Kerala SSLC

- Distance Education

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Affective Science

- Biological Foundations of Psychology

- Clinical Psychology: Disorders and Therapies

- Cognitive Psychology/Neuroscience

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational/School Psychology

- Forensic Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems of Psychology

- Individual Differences

- Methods and Approaches in Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational and Institutional Psychology

- Personality

- Psychology and Other Disciplines

- Social Psychology

- Sports Psychology

- Share Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Bilingualism: a cognitive and neural view of dual language experience.

- Judith F. Kroll Judith F. Kroll School of Education, University of California, Irvine

- , and Guadalupe A. Mendoza Guadalupe A. Mendoza School of Education, University of California, Irvine

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.900

- Published online: 15 August 2022

There has been an upsurge of research on the bilingual mind and brain. In an increasingly multilingual world, cognitive and language scientists have come to see that the use of two or more languages provides a unique lens to examine the neural plasticity engaged by language experience. But how? It is now uncontroversial to claim that the bilingual’s two languages are continually active, creating a dynamic interplay across the two languages. But there continues to be controversy about the consequences of that cross-language exchange for how cognitive and neural resources are recruited when a second language is learned and used actively and whether native speakers of a language retain privilege in their first acquired language. In the earliest months of life, minds and brains are tuned differently when exposed to more than one language from birth. That tuning has been hypothesized to open the speech system to new learning. But when initial exposure is to a home language that is not the majority language of the community—the experience common to heritage speakers—the value of bilingualism has been challenged, in part because there is not an adequate account of the variation in language experience. Research on the minds and brains of bilinguals reveals inherently complex and social accommodations to the use of multiple languages. The variation in the contexts in which the two languages are learned and used come to shape the dynamics of cross-language exchange across the lifespan.

- bilingualism

- language processing

- language learning

- language regulation

- cognitive control

- neural plasticity

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Psychology. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 14 November 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|185.66.14.133]

- 185.66.14.133

Character limit 500 /500

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Bilingualism: Consequences for Mind and Brain

Ellen bialystok, fergus im craik.

- Author information

- Copyright and License information

Building on earlier evidence showing a beneficial effect of bilingualism on children’s cognitive development, we review recent studies using both behavioral and neuroimaging methods to examine the effects of bilingualism on cognition in adulthood and explore possible mechanisms for these effects. This research shows that bilingualism has a somewhat muted effect in adulthood but a larger role in older age, protecting against cognitive decline, a concept known as “cognitive reserve”. We discuss recent evidence that bilingualism is associated with a delay in the onset of symptoms of dementia. Cognitive reserve is a crucial research area in the context of an aging population; the possibility that bilingualism contributes to cognitive reserve is therefore of growing importance as populations become increasingly diverse.

Why bilingualism?

It is generally believed that more than half of the world’s population is bilingual [ 1 ]. In each of the U.S. [ 2 ] and Canada [ 3 ], approximately 20% of the population speaks a language at home other than English. These figures are higher in urban areas, rising to about 60% in Los Angeles [ 4 ] and 50% in Toronto [ 3 ]. In Europe, bilingualism is even more prevalent: In a recent survey, 56% of the population across all European Union countries reported being functionally bilingual, with some countries recording particularly high rates, such as Luxembourg at 99% [ 5 ]. Bilinguals, therefore, make up a significant portion of the population. Importantly, accumulating research shows that the development, efficiency, and decline of crucial cognitive abilities are different for bilinguals than for monolinguals. What are these cognitive differences and how does bilingualism lead to these changes?

The context for examining how bilingualism affects cognitive ability is functional neuroplasticity, the study of how experience modifies brain structure and brain function. Such modifications have been found following experiences as diverse as juggling [ 6 ], video-game playing [ 7 ], careers in architecture [ 8 ] taxi-driving [ 9 ], and musical training [ 10 , 11 ]. Bilingualism is different from all of these: like juggling and playing video games it is intense, and like architecture and driving taxis in London it is sustained, but unlike these experiences, bilinguals are not typically pre-selected for talent or interest. Although bilinguals undoubtedly differ from monolinguals in certain ways, they generally did not choose bilingualism. Rather, the circumstances of their family, place of birth, or immigration history simply required that they learn more than one language.

What is different about bilingual minds?

It has long been assumed that childhood bilingualism affected developing minds but the belief was that the consequences for children were negative: learning two languages would be confusing [ 12 ]. A study by Peal and Lambert [ 13 ] cast doubt on this belief by reporting that children in Montreal who were either French-speaking monolinguals or English-French bilinguals performed differently on a battery of tests. The authors had expected to find lower scores in the bilingual group on language tasks but equivalent scores in nonverbal spatial tasks, but instead found that the bilingual children were superior on most tests, especially those requiring symbol manipulation and reorganization. This unexpected difference between monolingual and bilingual children was later explored in studies showing a significant advantage for bilingual children in their ability to solve linguistic problems based on understanding such concepts as the difference between form and meaning, that is, metalinguistic awareness [ 14 – 20 ] and nonverbal problems that required participants to ignore misleading information [ 21 , 22 ].

Research with adult bilinguals built on these studies with children and reported two major trends. First, a large body of evidence now demonstrates that the verbal skills of bilinguals in each language are generally weaker than are those for monolingual speakers of each language. Considering simply receptive vocabulary size, bilingual children [ 23 ] and adults [ 24 ] control a smaller vocabulary in the language of the community than do their monolingual counterparts. On picture-naming tasks, bilingual participants are slower [ 25 – 28 ] and less accurate [ 29 , 30 ] than monolinguals. Slower responses for bilinguals are also found for both comprehending [ 31 ] and producing words [ 32 ], even when bilinguals respond in their first and dominant language. Finally, verbal fluency tasks are a common neuropsychological measure of brain functioning in which participants are asked to generate as many words as they can in 60 seconds that conform to a phonological or semantic cue. Performance on these tasks reveals systematic deficits for bilingual participants, particularly in semantic fluency conditions [ 33 – 37 ], even if responses can be provided in either language [ 38 ]. Thus, the simple act of retrieving a common word is more effortful for bilinguals.

In contrast to this pattern, bilinguals at all ages demonstrate better executive control than monolinguals matched in age and other background factors. Executive control is the set of cognitive skills based on limited cognitive resources for such functions as inhibition, switching attention, and working memory [ 39 ]. Executive control emerges late in development and declines early in aging, and supports such activities as high level thought, multi-tasking, and sustained attention. The neuronal networks responsible for executive control are centered in the frontal lobes, with connections to other brain regions as necessary for specific tasks. In children, executive control is central to academic achievement [ 40 ], and in turn, academic success is a significant predictor of long term health and well being [ 41 ]. In a recent meta-analysis, Adesope et al. [ 42 ] calculated medium to large effect sizes for the executive control advantages in bilingual children and Hilchey and Klein [ 43 ] summarized the bilingual advantage over a large number of studies with adults. This advantage has been shown to extend into older age and protect against cognitive decline [ 25 , 44 , 45 ], a point we return to below.

In this review, we examine the evidence for bilingual advantages in executive control and explore the possible mechanisms and neural correlates that may help to explain them. Our conclusion is that lifelong experience in managing attention to two languages reorganizes specific brain networks, creating a more effective basis for executive control and sustaining better cognitive performance throughout the lifespan.

Language Processing in Bilinguals

Joint activation of languages.

A logical possibility for the organization of a bilingual mind is that it consists of two independently-represented language systems that are uniquely accessed in response to the context: A fluent French-English bilingual ordering coffee in a Parisian café has no reason to consider how to form the request in English, and a Cantonese-English bilingual studying psychology in Boston does not need to recast the material through Chinese. Yet, substantial evidence shows that this is not how the bilingual mind is organized. Instead, fluent bilinguals show some measure of activation of both languages and some interaction between them at all times, even in contexts that are entirely driven by only one of the languages.

The evidence for this conclusion comes from psycholinguistic studies using such tasks as cross-language priming (in which a word in one language facilitates retrieval of a semantically related word in the other language) and lexical decision (in which participants decide whether a string of letters is a legal word in one of the languages) that show the influence of the currently unused language for both comprehension and production of speech [ 46 – 52 ]. Further evidence comes from patient studies showing intrusions from the irrelevant language or inappropriate language switches [ 53 ], and imaging studies indicating involvement of the non-target language while performing a linguistic task in the selected language [ 54 – 56 ]. Using eye-tracking technology, for example, Marian, Spivey, and Hirsch [ 57 ] reported that English-Russian bilinguals performing a task in English in which they had to look at the named picture from four alternatives were distracted by a picture whose name shared phonology with Russian even though there was no connection to the meaning of the target picture and no contextual cues indicating that Russian was relevant. Similarly, Thierry and Wu [ 58 ] presented English monolinguals, Chinese-English bilinguals, and Chinese monolinguals with pairs of words in English (translated to Chinese for Chinese monolinguals) and asked participants to decide if the words were semantically related or not. The manipulation was that half of the pairs contained a repeated character in the written Chinese forms, even though that orthographic feature was unrelated to the English meaning. Waveforms derived from analyses of electroencephalography (EEG) are used to indicate the neuronal response to language on a millisecond by millisecond scale. This event-related potential (ERP) signals the effort associated with integrating the meaning of words in a negative waveform about 400 milliseconds after the stimulus, a waveform called the N400. The more similar the words are to each other, the smaller is the amplitude of the N400. In the study by Thierry and Wu, semantic relatedness was associated with significantly smaller N400 amplitude in all groups as expected, but the repeated character also led to smaller N400 for the two Chinese groups. Thus, although irrelevant to the task, participants were accessing the Chinese forms when making judgments about the semantic relation between English words. Subsequent research has refined these results by showing their basis in the phonology rather than the orthography of spoken language [ 59 ] and extended the phenomenon to the phonological hand forms of American Sign Language [ 60 ].

This joint activation is the most likely mechanisms for understanding the consequences of bilingualism for both linguistic and nonlinguistic processing. For linguistic processing, joint activation creates an attention problem that does not exist for monolinguals: In addition to selection constraints on such dimensions as register, collocation, and synonymy, the bilingual speaker also has to select the correct language from competing options. Although joint activation creates a risk for language interference and language errors, these rarely occur, indicating that the selection of the target language occurs with great accuracy. However, this need to select at the level of language system makes ordinary linguistic processing more effortful for bilinguals than monolinguals and explains some of the costs in psycholinguistic studies described above. For nonlinguistic processing, the need to resolve competition and direct attention is primarily the responsibility of general cognitive systems, in particular executive functions. The possible influence of linguistic processes on nonlinguistic executive control has enormous consequences for lifespan cognition and is discussed in the next section.

Consequences of joint activation

An appealing suggestion for how the executive control system achieves linguistic selection in the context of joint activation is through inhibition of the non-target language. At least two influential models have been proposed that place inhibition at the center of this selection. The first, the Inhibitory Control model [ 61 ] is based on the Supervisory Attentional System [ 62 ] and extends a domain-general and resource-limited attention system to the management of competing languages. The second, the Bilingual Interactive Activation Model (BIA+) [ 63 ], uses computer simulation to model lexical selection from both intralingual and extralingual competitors. Although both models assign a primary role to inhibition, they are quite different from each other and address a different aspect of the selection problem. It is useful, therefore, to consider the distinction between global inhibition and local inhibition proposed by De Groot and Christoffels [ 64 ]. Global inhibition refers to suppression of an entire language system, as in inhibiting French when speaking English, and local inhibition refers to inhibition of a specific competing distractor, such as the translation equivalent of the required concept. Both processes are required for fluent language selection but the two are carried out differently. Guo, Liu, Misra, and Kroll [ 65 ] used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to demonstrate the recruitment of different systems for each of global inhibition (dorsal left frontal gyrus and parietal cortex) and local inhibition (dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, supplementary motor area) in a sample of Chinese-English bilinguals, and validated their distinct roles in bilingual language control. While Green’s inhibitory control model is consistent with both types of inhibition, Dijkstra’s BIA+ modeling item selection in local inhibition.

These types of inhibition also differ in their primary domain of influence, with local inhibition largely affecting linguistic performance and global inhibition affecting both linguistic and cognitive performance. The linguistic outcomes of inhibition are reduced speed and fluency of lexical access for bilinguals as described above. However, performance also requires a selection bias towards the target language, showing a role for activation [ 66 , 67 ] as well as inhibition. These alternatives are not mutually exclusive but indicate the need for a more complete description of how attention is managed in bilingual language processing. Ultimately the degree of both inhibition and activation are relative rather than absolute and will be modulated by contextual, linguistic, and cognitive factors. The cognitive outcomes of linguistic inhibition are enhanced attentional control and will be described more fully in the next section. Importantly, the cognitive and linguistic outcomes are related. Three studies have reported a relationship between inhibition and ability in verbal and nonverbal tasks by showing a correlation between Stroop task performance and competing word selection [ 68 ], Simon task performance and language switching in picture naming [ 69 ], and cross-language interference and a variety of executive control measures [ 70 ]. Such results point to an extensive reorganization of cognitive and linguistic processes in bilinguals.

Cognitive networks in bilinguals

Bilingual performance on conflict tasks.