Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Download Free PDF

The Impacts of TikTok as a Social Content Platform on the Academic Productivity of Grade 11 STEM Students at Cebu Doctors' University

This research investigates the effects of TikTok, a popular social content platform, on the academic productivity of Grade 11 STEM students at Cebu Doctors' University. With TikTok's growing influence on student behavior and learning, this study aims to evaluate how engagement with the platform impacts students' academic performance and productivity. Utilizing a mixed-methods approach, the research combines quantitative surveys to measure time spent on TikTok and academic outcomes, with qualitative interviews to explore students' perceptions of how TikTok affects their study habits and academic focus. Preliminary findings suggest that while TikTok provides educational content and can enhance learning through interactive and engaging materials, excessive use may lead to distractions and reduced academic productivity. The study underscores the need for balanced media consumption and effective time management strategies to optimize academic performance while leveraging the educational potential of social content platforms.

Related papers

Galaxy International Interdisciplinary Research Journal, 2024

It is well-known that TikTok is a cutting-edge academic aid that significantly improves students' educational experiences thanks to its dynamic and entertaining platform. Initially perceived as purely an entertainment platform, TikTok has developed into an important instructional resource that can greatly improve students' learning outcomes. The aim of this literature review is to examine and consolidate the existing body of knowledge regarding TikTok's adverse impacts on students' educational journey. This review explores how TikTok affects students' lives in several areas, including academic achievement. The findings of the collected evaluations in different literature reviews show both TikTok's positive and, at the same time, some negative features while also shedding light on the platform's possible risks and effects on students. Students may stay interested and involved in academics while gaining crucial digital literacy skills by integrating TikTok into their educational journey. It is recommended that teachers improve their pedagogical approach and reach a wider audience by sharing creative teaching techniques, classroom experiences, and motivational content on TikTok.

THE 4TH INTERNATIONAL SEMINAR ON CHEMICAL EDUCATION (ISCE) 2021

Ubiquitous Learning: An International Journal, 2023

In recent years, TikTok, a video-based application, has become immensely popular, especially among young social media users. During the COVID-19 pandemic, TikTok also proved to be useful in remote learning. The present study examines the use of TikTok videos among university students in Egypt, with a specific focus on how these videos enhance student online engagement in virtual classrooms. We also evaluate the moderating effect of gender, age, and academic major on the relationship between the adoption and educational use of TikTok and student online engagement. The results of a survey conducted among a total of 250 students at Cairo University from different age groups, gender, and majors revealed statistically significant and positive correlations between the adoption of TikTok (perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and social influence), educational use of TikTok (via facilitating access to information and sharing material), and online student engagement. The results also showed two significant moderations based on gender and age. First, we found that access to information via TikTok contributed more to the online engagement of male students as compared to their female counterparts. Second, with increasing age, sharing information and materials with the help of TikTok was found to have a greater effect on online student engagement. While it remains to be established whether these findings can be generalized to other universities and educational institutes in Egypt, the adoption and educational use of TikTok can be considered to be a promising way to facilitate online education.

The International Journal of Indian Psychology, 2021

Social media and academic grades are two of the most important things in an average student's life. Several factors play an important role in determining whether he achieves first class, second class, third class, or distinction. This study aims to find out the extent to which Social Media impacts the student's academic results. Using Pearson's Correlation test, the study determined that there was a negative impact of social media usage on academic performance. Furthermore, Pearson's Correlation test also showed us that the distraction caused by social media impact their academic performance. There is a high need to include various beneficial aspects of social media in a classroom's teachings. Instead of outright condemning social media usage by students, education systems and academics should try and make it a part of the educational curriculum. The longer the academicians try and stick to the age-old teaching method from a constraint boundary of class and books, the more we unequip students from the necessary skillsets required to bring a change and lead.

American Scientific Research Journal for Engineering, Technology, and Sciences, 2020

This research paper is aimed at shedding light on the use of the mobile application Tiktok, it concluded that the use of the application, has had a very little negative impact on the main target user base. The research outlines to a certain degree some difficulties in the management of the application but in comparison with similar social media applications, they appear to be few. This research has concluded that the use of the application seems to be of more concern to spectators of the users than the actual users. This research has also been able to map out the spread of Tiktok over the past 3 years and how it has become a significant participant in the role of influencers, creating an entrepreneurial possibility with its growth. This research recommends further research into the use of popular social media apps and further monitoring of the expansion of the popularity of the usages of social media apps in general.

International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications (IJSRP), 2020

Along with the vast development of social media, such as Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube, more new social media platforms such as Tiktok have emerged in the public domain. TikTok, an application that is available for everyone to publish their videos, which length of the video varies from 15 seconds to 1 minute, has been rapidly used to gain popularity and cure boredom especially among teenagers. The videos include daily entertainment, talent shows, and popularization of knowledge and so on. This study therefore evaluated the uses and gratifications of the Tiktok platform by students of Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University. The main objective of the study was to ascertain the frequency of usage and the gratifications students derive from using the Tiktok platform. Anchored on the Uses and Gratifications theory, the study adopted Survey Research method to draw a sample size of 400 from students of Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University, Igbariam Campus using purposive sampling technique and the questionnaire as the instrument for data collection. The study found that there is a high frequency of usage of the Tiktok platform among students of Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University. Learning new things, obtaining leisure and entertainment, expressing themselves freely and also making new friends are some of the gratifications the respondents derive from using the Tiktok platform. The study recommends among others that students should rather utilize the instrumentality of Tiktok for their academic improvement rather than all entertainment.

National Conference at MP Birla Institute of Management , Bangalore, 2019

Presently, social networking platforms (SNPs) like Facebook, WhatsApp, Twitter, Instagram etc., are most sought after communication tools all over the world. Millions of people are spending long hours on SNPs using mobiles, desktops, laptops etc., with associated benefits and drawbacks. Students are no exception to this phenomenon. Every day, more and more number of students from school to college level is hooking up to SNPs frequently, which is a cause of concern for the stakeholders in education system. This realism has prompted to find out the current usage and engagement levels of SNPs by management students and their influence on the academic performance. Findings show that around half of the students’ access SNPs more than four times a day for around two and half hours on an average to communicate with friends, share experiences and discuss various social issues. Nonetheless, they also share academics on SNPs with equal fervour. In spite of the substantial amount of time spent on SNPs, students’ academic performance was not affected as evident from the higher grades obtained and substantiated by the low correlation coefficient(r =0.012) with no statistical significance. Key Words: Academic Performance, Communication, Mobile, Students, Social Networking Platform

International Journal of Educational Management and Development Studies

Social media has become integral to people’s lives; revolutionizing communication and providing opportunities to learn about societal trends and issues. This study aimed to examine the influence of social media on the academic performance of junior high school students in Marawi City, Lanao Del Sur, Philippines during the 2022-2023 academic year. It employed a descriptive-correlational research approach to explore the impact of social media usage on academic socialization, entertainment, and informative aspects and its association with academic performance. The study used simple random sampling to select junior high school students from the target school. The findings indicated that students utilized social media for various purposes, including conducting research, problem-solving, peer interaction, curriculum understanding, and collaborative learning. Participants agreed that social media positively influenced their academic, socialization, entertainment, and informative experience...

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

American Scientific Research Journal for Engineering, Technology, and Sciences, 2018

Jurnal Basicedu

International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering (IJRTE), 2019

Indonesian Journal of Educational Research and Technology, 2021

ArXiv, 2021

International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research

Asian Journal of Education and Social Studies, 2021

EMMANUEL RYAN P. FRANCISCO, 2018

Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities

Priority-The International Business Review, 2023

European Journal of Medical and Health Sciences

Editorial Board of Jilin University , 2022

The Journal of Social Media for Learning: Winter Edition , 2022

Global Mass Communication Review, 2020

Media Watch, 2024

Universal Journal of Educational Research, 2020

International Journal For Multidisciplinary Research, 2024

Psychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 2024

Related topics

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

On the Psychology of TikTok Use: A First Glimpse From Empirical Findings

Christian montag, jon d elhai.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Edited by: Uichin Lee, KAIST, South Korea

Reviewed by: Bahiyah Omar, Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM), Malaysia; Dongwhan Kim, Yonsei University, South Korea

*Correspondence: Christian Montag [email protected]

This article was submitted to Digital Public Health, a section of the journal Frontiers in Public Health

Received 2020 Dec 14; Accepted 2021 Jan 18; Collection date 2021.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

TikTok (in Chinese: DouYin; formerly known as musical.ly) currently represents one of the most successful Chinese social media applications in the world. Since its founding in September 2016, TikTok has seen widespread distribution, in particular, attracting young users to engage in viewing, creating, and commenting on “LipSync-Videos” on the app. Despite its success in terms of user numbers, psychological studies aiming at an understanding of TikTok use are scarce. This narrative review provides a comprehensive overview on the small empirical literature available thus far. In particular, insights from uses and gratification theory in the realm of TikTok are highlighted, and we also discuss aspects of the TikTok platform design. Given the many unexplored research questions related to TikTok use, it is high time to strengthen research efforts to better understand TikTok use and whether certain aspects of its use result in detrimental behavioral effects. In light of user characteristics of the TikTok platform, this research is highly relevant because TikTok users are often adolescents and therefore from a group of potentially vulnerable individuals.

Keywords: TikTok, DouYin, musical.ly, personality, uses and gratification, social media, social media addiction, problematic social media use

Musical.ly was founded in September 2016 by Zhang Yiming. Beijing Bytedance Technology acquired the application musical.ly in November 2017 and renamed the app to TikTok. In a short time period, this application became the most successful app from Chinese origin in terms of global distribution ( 1 ). As of November 2020, 800 million monthly users have been reported 1 , and 738 million first-time installs in 2019 have been estimated 2 . TikTok use is allowed for those 13 years or older, but direct messaging between users is allowed only for those 16 or older (in order to protect young users from grooming) 3 . In China, the main users of TikTok are under 35 years old (81.68% (2)). Meanwhile, to protect children and adolescents from unsuitable content (such as smoking, drinking, or rude language), TikTok's engineers also developed a version of the app, which filters inappropriate content for young users ( 2 ). Of note, at the moment of writing, the app operates as TikTok on the global market and as DouYin on the Chinese market ( 3 ). Similarities and differences of the twin apps are further described with a content analysis by Sun et al. ( 4 ).

The TikTok application available for Android and Apple smartphones enables creation of short videos where users can perform playback-videos to diverse pop-songs, to name one very prominent feature of the platform. These so-called “LipSync-Videos” can be shared with other users, downloaded for non-commercial purposes, commented upon and of course attached with a “Like.” Not only are playback-videos uploaded on TikTok but also users view a large amount of video content. Users can also call out for “challenges,” where they define which performance should be created by many users. As a consequence, TikTok users imitate the content or interact with the original video.

As the large user numbers in a very short time-window demonstrate, TikTok not only represents a global phenomenon but also has been criticized with respect to data protection issues/privacy ( 5 , 6 ), spreading hate ( 7 ) and might serve as a platform engendering cyberbullying ( 8 , 9 ). Given the many young users of this platform (e.g., 81.68% of China users of Tiktok are under 35 years old—see above, and 32.5% of the US users are 19 years old and younger) 4 , it is of particular relevance to better understand the motivation to use TikTok, alongside related topics. Such an understanding might also be relevant because recent research suggests that TikTok can be a potent channel to inform young persons on health-relevant information ( 10 – 12 ), on official information release from the government ( 13 ), political discussions ( 14 ), tourism content ( 15 ), live online sales ( 16 ), and even educational content ( 17 ). There even have been video-posts analyzed in a scientific paper related to radiology ( 18 ). Clearly, young TikTok users are also confronted with harmful health content, including smoking of e-cigarettes ( 19 ). Moreover, the health information learned from TikTok videos often does not meet necessary standards—as is discussed in a paper on acne ( 20 ). Finally, there arises the problem that while creating content, children's/adolescent's private home bedrooms from which they create TikTok videos become visible to the world, posing privacy intrusions ( 21 ). The many obviously negative aspects of TikTok use are in itself important further research leads. From a psychological perspective, we take a different path with the present review and try to better understand why people use TikTok, who uses the platform, and also how people use TikTok.

Why do People Use TikTok?

This question can be answered from different perspectives. One perspective providing an initial answer and—likely being true for most social media services—has been put forward by Montag and Hegelich ( 22 ). Social media companies have created services being highly immersive, aiming to capture the attention of users as long as possible ( 23 ). As a result of a prolonged user stay, social media companies obtain deep insights into psychological features of their users ( 24 ), which can be used for microtargeting purposes ( 25 ). Such immersive platform design also likely drives users with certain characteristics into problematic social media use ( 26 ) or problematic TikTok use (addictive-like behavior), but this aspect relating to TikTok use is understudied. Nevertheless, reinforcement of TikTok usage is also very likely reached by design-elements such as “Likes” ( 27 ), personalized and endless content available ( 23 ). TikTok's “For You”-Page (the landing page) learns quickly via artificial intelligence what users like, which likely results in longer TikTok use than a user intended, which may cause smartphone TikTok-related addictive behavior ( 2 ). This said, these ideas put forward still need to be confirmed by empirical studies dealing exclusively with TikTok. In this realm, an interesting research piece recently investigated less studied variables such as first-person camera views, but also humor on key variables such as immersion and entertainment on the TikTok platform ( 28 ), again all of relevance to prolong user stay.

The other perspective one could choose to address why people use TikTok stems from uses and gratification theory ( 29 , 30 ). The simple idea of this highly influential theory is that use of certain media can result in gratification of a person's needs ( 30 ), and only if relevant needs of a person are gratified by particular media, users will continue media use—here digital platform or social media use.

A recent paper by Bucknell Bossen and Kottasz ( 31 ) provided insight that, in particular, gratification of entertainment/affective needs was the most relevant driver to understand a range of behaviors on TikTok, including passive consumption of content, but also creating content and interacting with others. In particular, the authors summarized that TikTok participation was motivated by needs to expand one's social network, seek fame, and express oneself creatively. Recent work by Omar and Dequan ( 32 ) also applied uses and gratification theory to better understand TikTok use. In their work, especially the need for escapism predicted TikTok content consumption, whereas self-expression was linked to both participating and producing behavior. A study by Shao and Lee ( 33 ) not only applied uses and gratification theory to understand TikTok use but also shed light on TikTok use satisfaction and the intention to further use TikTok. In line with findings from the already mentioned works, entertainment/information alongside communication and self-expression were discussed as relevant use motives (needs to be satisfied by TikTok use). Satisfaction with TikTok was investigated as a mediator between different motives to use TikTok and to continue TikTok use. We also mention recent work being unable to link TikTok use to well-being, whether in a positive or negative way ( 34 ). Finally, Wang et al. ( 35 ) underlined the overall relevance of uses and gratification theory to understand TikTok use and presented need variables in cognitive and affective domains as relevant to study, but also personal/social integration and relief of pressure. In this context, we also mention the view of Shao ( 2 ) who put forward that, in particular, young people use TikTok for positioning oneself in their peer group and to understand where he/she stands in the peer group. Thus, TikTok is also relevant for identity formation of young persons and obtaining feedback to oneself.

Further theories need to be mentioned, which can explain why people are using the TikTok platform: Social Impact Theory and Self-Determination Theory. To our knowledge, these theories have not been sufficiently addressed empirically so far with respect to TikTok use, but are well known to be of relevance to understand social media use in general and are therefore mentioned.

Clearly, an important driver of social media use can be power, hence, reaching out to many and influencing other persons ( 36 ). Here, the classic Social Impact Theory (SIT) by Latané ( 37 ) tries to understand how to best measure the impact of people on a single individual/individuals. This theory—originating in the pre-social-media-age—gained a lot of visibility with the rise of social media services because, in particular, in the age of filter bubbles, fake news, and misinformation campaigns ( 38 , 39 ), it is interesting to understand how individual users on social media are socially influenced by others, for instance, in the area of their (political) attitudes. The SIT postulates three highly relevant factors called strength, immediacy, and number (of sources) to predict such a social impact. Ultimately, applying this theory to better understand TikTok use also needs to take into account that users differ in terms of their active and passive use.

The Self-Determination Theory (SDT) has been proposed by Ryan and Deci ( 40 ) and belongs to the most influential motivation theories of human behavior. Hence, it clearly can also be used to explain why people are motivated to use a social media service ( 41 , 42 ). According to SDT, motivated behavior (here using TikTok) should be high, when such a platform enables users to feel competence, autonomy, and being connected with others. Design of the platform can help to trigger related psychological states (e.g., push notifications can trigger fear of missing out, hence, not being connected to significant others) ( 43 ); but clearly also, individual differences play a relevant role, and this should be discussed as the next important area in this work. As with the SIT, applying SDT to better understand TikTok use will also need to take into account different kinds of TikTok use. A sense of self-determination might rise to different levels, when users are actively or passively using TikTok—and this also represents an interesting research question.

Who Uses TikTok and Who Does Not?

The aforementioned statistics show that TikTok users are often young. Bucknell Bossen and Kottasz ( 31 ) illustrated that, in particular, young users are also those who seem to be particularly active on the platform, and thus share much information. Given that, in particular, young users often do not foresee consequences of self-disclosure, it is of high importance to better protect this vulnerable group from detrimental aspects of social media use. Beyond age, statistics suggest that more females than males use the platform 5 , something also observed with other platforms ( 44 – 46 ). First, insights from personality psychology provided further information on associations between characteristics of TikTok users and how they use it (see also the next How Do People Use TikTok? section): The widely applied Big Five Personality traits called openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism (acronym OCEAN) were all robustly linked to producing, participating, and consuming behavior on TikTok, with the exception of agreeableness only being linked to consuming behavior ( 32 ). Using a hierarchical regression model inserting both personality variables and motives from uses and gratification theory, it became apparent that the latter variables seemed to outweigh the personality variables in their importance to predict TikTok usage. Lu et al. ( 47 ) used data from China to investigate individual differences in DouYin (again the Chinese version of TikTok) use. Among others, they observed that people refraining from using DouYin did so out of fear of getting “addicted” to the application [see also ( 48 )]. This needs to be further systematically explored with the Big Five model of personality (or HEXACO, as the personality models dominating modern personality psychology at the moment). Without doubt, it will be also highly important to better understand how the variables of socio-demographics and personality interact on TikTok use, also in the realm of active/passive use of the platform. Active use would describe a high engagement toward the platform including commenting and uploading videos. Passive usage would reflect in browsing and simply consuming videos. The need to distinguish between active and passive use of social media has been also recently empirically supported by Peterka-Bonetta et al. ( 49 ).

How do People Use TikTok?

In the Why Do People Use TikTok? section, we already mentioned that users can passively view content, but also create content or interact with others. Studies comprehensively showing how many and which types of people use TikTok with respect to these behavioral categories are lacking (but TikTok likely has at least some of these insights). A recent review by Kross et al. ( 50 ) on “social media (use) and well-being” summarized that several psychological processes such as upward social comparison (perhaps also happening in so-called “challenges” on TikTok) or fear of missing out ( 43 ) are related to negative affect and might have detrimental effects on the usage experience and/or TikTok users' lives in general. Overall, the psychological impact of the TikTok platform might also be very likely, in particular, when adolescents often imitate their idols in “LipSync-Videos” ( 51 ). The kind of influence of such behavior on the development of one's own identity and self-esteem (self-confidence) ( 52 ) will be a matter of important psychological discussion, but it is too early to speculate further on potential psychological effects here, both in the positive or negative direction ( 53 ). Moreover, whether such effects will be of positive or negative nature, we mention the importance to not overpathologize everyday life behavior ( 54 ).

In sum, much of what we know with respect to platforms such as Instagram, Facebook, WhatsApp, or even WeChat ( 56 ) needs to still be investigated in the context of TikTok, to understand if psychological observations made for other social media channels can be transferred “one-on-one” to TikTok. For instance, illustrating differences between social media platforms, Bhandari and Bimo ( 57 ) suggested in their analysis of TikTok that in contrast to other platforms, “the crux of interaction is not between users and their social network, but between a user and what we call an ‘algorithmized’ version of self.” Opening TikTok immediately results in being captured by a personalized stream of videos. Therefore, we believe it to be unlikely that all insights from social media research can be easily transferred to TikTok because it is well-known that each social media platform has a unique design also attracting different user groups ( 45 ), and they elicit different immersive or “addictive” potential ( 58 ). Please note that we use the term “addictive” only in quotation marks, given the ongoing debate on the actual nature of excessive social media use ( 59 , 60 ). This said, we explicitly mention that the study of problematic social media use represents a very important topic ( 61 ), although at the moment, this condition—of relevance for the mental health sciences—is not officially recognized by the World Health Organization. Despite the ongoing controversy, nevertheless, it has been recently pointed out that social media companies are responsible for the well-being of users, too ( 55 ).

Conclusions and Outlook

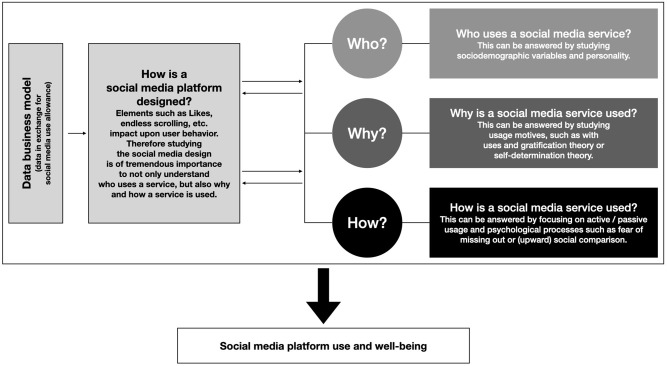

Although user numbers are high and TikTok represents a highly successful social media platform around the globe, we know surprisingly less about psychological mechanisms related to TikTok use. Most research has been carried out so far yielding insights into user motives applying uses and gratification theory. Although this theory is of high importance to understand TikTok use, it is still rather broad and general. In particular, when studying a platform such as TikTok—receiving attention at the moment from a lot of young users—more specific needs or facets of the broad dimensions of uses and gratification theory (such as social usage) being more strongly related to the needs of adolescents might need more focus. One such focus could be a stronger emphasis on the study of self-esteem ( 62 ) in the context of TikTok use. Work beyond this area, e.g., investigating potential detrimental aspects, are scarce, but will be important. In particular, we deem this to be true, as TikTok attracts very young users, being more vulnerable to detrimental aspects of social media use ( 63 ). We believe that it is also high time for researchers to put research energy in the study of TikTok and to do so in a comprehensive manner. Among others, it needs also to be studied how active and passive use impact on the well-being of the users. This means that the here-discussed how-, why- , and who- questions need to be studied together in one framework, and this needs to be done against the data business model and its immersive platform design. The key ideas of this review to understand TikTok use and related aspects such as well-being of the users are presented in Figure 1 .

In order to understand the relationship between a social media service such as TikTok and human psychological processes and behavior, one needs to answer the who-, why-, and how-questions, also against the background of the social media platform design. Please note that the platform design itself is driven by the data business model. Social media usage and its association with psychological/behavioral variables such as well-being, online-time, and so on can be best understood by investigating these variables in one model, at best also investigating potential interactions of variables. These ideas have also been described in parts in Montag and Hegelich ( 22 ), Kross et al. ( 50 ), and Montag et al. ( 55 ). The figure does not exclusively mention TikTok because we are convinced that the presented details are true for all research agendas aiming at a better understanding of the relationship between social media use and well-being.

Author Contributions

CM wrote the first draft of this review article. HY screened the Chinese literature and added relevant work from a Chinese perspective to the review. Finally, JDE critically worked over the complete draft. All authors agreed upon the final version of the article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1 https://www.omnicoreagency.com/tiktok-statistics/ (accessed March 9, 2021).

2 https://www.statista.com/statistics/1089420/tiktok-annual-first-time-installs/ (accessed March 9, 2021).

3 https://www.heise.de/newsticker/meldung/Ab-16-TikTok-fuehrt-Mindestalter-fuer-Direktnachrichten-ein-4703887.html (accessed March 9, 2021).

4 https://www.statista.com/statistics/1095186/tiktok-us-users-age/ (accessed March 9, 2021).

5 https://www.statista.com/statistics/1095196/tiktok-us-age-gender-reach/ (accessed March 9, 2021).

- 1. Xiong Y, Ji Y. From content platform to relationship platform: analysis of the attribute change of Tiktok short video. View Publish. (2019) 4:29–34. (Citation has been translated from Chinese language.) [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Shao Z. Analysis of the characteristics, challenges and future development trends of Tik Tok. Mod Educ Tech. (2018) 12:81–7. (Citation has been translated from Chinese language.) [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Kaye DBV, Chen X, Zeng J. The co-evolution of two Chinese mobile short video apps: Parallel platformization of Douyin and TikTok. Mobile Media Commun. (2020). 10.1177/2050157920952120. [Epub ahead of print]. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Sun L, Zhang H, Zhang S, Luo J. Content-based analysis of the cultural differences between TikTok and Douyin. arXiv[Preprint].arXiv:2011.01414. (2020). Available online at: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2011.01414v1.pdf

- 5. Neyaz A, Kumar A, Krishnan S, Placker J, Liu Q. Security, privacy and steganographic analysis of FaceApp and TikTok. Int J Comp Sci Sec (IJCSS). (2020) 14:38–59. Available online at: https://www.cscjournals.org/library/manuscriptinfo.php?mc=IJCSS-1552 [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Wang J. From Banning to Regulating TikTok: Addressing Concerns of National Security, Privacy, and Online Harms. (2020). Available online at: https://www.fljs.org/sites/www.fljs.org/files/publications/From%20Banning%20to%20Regulating%20TikTok.pdf

- 7. Weimann G, Masri N. Research note: spreading hate on TikTok. Stud Conf Terror. (2020) 20:1–14. 10.1080/1057610X.2020.1780027 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Anderson KE. Getting acquainted with social networks and apps: It is time to talk about TikTok. Library Hi Tech News. (2020) 37:7–12. 10.1108/LHTN-01-2020-0001 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Kumar VL, Goldstein MA. Cyberbullying and adolescents. Curr Pediatr Rep. (2020) 8:86–92. 10.1007/s40124-020-00217-6 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Basch CH, Hillyer GC, Jaime C. COVID-19 on TikTok: Harnessing an emerging social media platform to convey important public health messages. Int J Adolesc Med Health. (2020). 10.1515/ijamh-2020-0111. [Epub ahead of print]. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Comp G, Dyer S, Gottlieb M. Is TikTok the next social media frontier for medicine? AEM Educ Train. (2020). 10.1002/aet2.10532. [Epub ahead of print]. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Ostrovsky AM, Chen JR. TikTok and its role in COVID-19 information propagation. J Adolesc Health. (2020) 67:730. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.07.039 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Jiang J, Wang W. Research on Government Douyin for public opinion of public emergencies: comparison with government microblog. J Intellig. (2020) 39:100–106. (Citation has been translated from Chinese language.) [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Medina Serrano JC, Papakyriakopoulos O, Hegelich S. Dancing to the Partisan Beat: a first analysis of political communication on TikTok. In: 12th ACM Conference on Web Science. (2020). p. 257–266. 10.1145/3394231.3397916 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Du X, Liechty T, Santos CA, Park J. ‘I want to record and share my wonderful journey’: Chinese Millennials' production and sharing of short-form travel videos on TikTok or Douyin. Curr Issues Tour. (2020) 20:1–13. 10.1080/13683500.2020.1810212 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Li L, Gao S. TikTok marketing strategies from the perspective of audience psychology. J Xiamen Univer Technol. (2020) 28:18–23. (Citation has been translated from Chinese language.) [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Hayes C, Stott K, Lamb KJ, Hurst GA. “Making every second count”: utilizing TikTok and systems thinking to facilitate scientific public engagement and contextualization of chemistry at home. J Chem Educ. (2020) 97:3858–66. 10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00511 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Lovett JT, Munawar K, Mohammed S, Prabhu V. Radiology content on TikTok: current use of a novel video-based social media platform and opportunities for radiology. Curr Prob Diag Radiol. (2021) 50, 126–31. 10.1067/j.cpradiol.2020.10.004 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Tan ASL, Weinreich E. #PuffBar: How do top videos on TikTok portray Puff Bars? Tobacco Control. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-055970 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Zheng DX, Ning AY, Levoska MA, Xiang L, Wong C, Scott JF. Acne and social media: a cross-sectional study of content quality on TikTok. Pediatr Derm. (2020). 10.1111/pde.14471. [Epub ahead of print]. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Kennedy M. ‘If the rise of the TikTok dance and e-girl aesthetic has taught us anything, it's that teenage girls rule the internet right now’: TikTok celebrity, girls and the Coronavirus crisis. Eur J Cult Stud. (2020) 23:1069–76. 10.1177/1367549420945341 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Montag C, Hegelich S. Understanding detrimental aspects of social media use: will the real culprits please stand up? Front Sociol. (2020) 5:94. 10.3389/fsoc.2020.599270 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Montag C, Lachmann B, Herrlich M, Zweig K. Addictive features of social media/messenger platforms and freemium games against the background of psychological and economic theories. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:2612. 10.3390/ijerph16142612 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Marengo D, Montag C. Digital phenotyping of big five personality via Facebook data mining: a meta-analysis. Dig Psychol. (2020) 1:52–64. 10.24989/dp.v1i1.1823 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Matz SC, Kosinski M, Nave G, Stillwell DJ. Psychological targeting as an effective approach to digital mass persuasion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2017) 114:12714–9. 10.1073/pnas.1710966114 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Sindermann C, Elhai JD, Montag C. Predicting tendencies towards the disordered use of Facebook's social media platforms: On the role of personality, impulsivity, social anxiety. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 285:112793. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112793 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Marengo D, Montag C, Sindermann C, Elhai JD, Settanni M. Examining the Links between Active Facebook Use, Received Likes, Self-Esteem and Happiness: A Study using Objective Social Media Data. Telem Inform. (2020) 10:1523. 10.1016/j.tele.2020.101523 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Wang Y. Humor and camera view on mobile short-form video apps influence user experience and technology-adoption intent, an example of TikTok (DouYin). Comp Hum Behav. (2020) 110:106373. 10.1016/j.chb.2020.106373 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Ahlse J, Nilsson F, Sandström N. It's Time to TikTok: Exploring Generation Z's Motivations to Participate in #Challenges. (2020). Available online at: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:hj:diva-48708

- 30. Katz E, Blumler JG, Gurevitch M. Uses and gratifications research. Public Opin Q. (1973) 37:509–23. [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Bucknell Bossen C, Kottasz R. Uses and gratifications sought by pre-adolescent and adolescent TikTok consumers. Young Cons. (2020) 21:463–78. 10.1108/YC-07-2020-1186 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Omar B, Dequan W. Watch, Share or Create: The Influence of Personality Traits and User Motivation on TikTok Mobile Video Usage. International Association of Online Engineering. (2020). Available online at: https://www.learntechlib.org/p/216454/ [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Shao J, Lee S. The effect of chinese adolescents' motivation to use Tiktok on satisfaction and continuous use intention. J Converg Cult Technol. (2020) 6:107–15. 10.17703/JCCT.2020.6.2.107 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Masciantonio A, Bourguignon D, Bouchat P, Balty M, Rimé B. Don't put all social network sites in one basket: Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, TikTok, and their relations with well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. PsyArXiv. (2020). 10.31234/osf.io/82bgt [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Wang Y, Gu T, Wang S. Causes and characteristics of short video platform internet community taking the TikTok short video application as an example. In: 2019 IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics - Taiwan (ICCE-TW) Yilan. (2019). p. 1–2. 10.1109/ICCE-TW46550.2019.8992021 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Sariyska R, Lachmann B, Cheng C, Gnisci A, Sergi I, Pace A, et al. The motivation for Facebook use – is it a matter of bonding or control over others? J Individ Differ. (2018) 40:26–35. 10.1027/1614-0001/a000273 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Latané B. The psychology of social impact. Am Psychol. (1981) 36:343–56. 10.1037/0003-066X.36.4.343 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Sindermann C, Cooper A, Montag C. A short review on susceptibility to falling for fake political news. Curr Opin Psychol. (2020) 36:44–8. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.03.014 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Sindermann C, Elhai JD, Moshagen M, Montag C. Age, gender, personality, ideological attitudes and individual differences in a person's news spectrum: How many and who might be prone to “filter bubbles” and “echo chambers” online? Heliyon. (2020) 6:e03214. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03214 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. (2000) 55:68–78. 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 41. Ferguson R, Gutberg J, Schattke K, Paulin M, Jost N. Self-determination theory, social media and charitable causes: An in-depth analysis of autonomous motivation. Eur J Soc Psychol. (2015) 45:298–307. 10.1002/ejsp.2038 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 42. Miller LM, Prior DD. Online social networks and friending behaviour: A self-determination theory perspective. In: ANZMAC 2010: Proceedings : Doing More with Less. Australian and New Zealand Marketing Academy Conference. (2010). Available online at: https://researchers.mq.edu.au/en/publications/online-social-networks-and-friending-behaviour-a-self-determinati

- 43. Elhai JD, Yang H, Montag C, Elhai JD, Yang H, Montag C. Fear of missing out (FOMO): overview, theoretical underpinnings, and literature review on relations with severity of negative affectivity and problematic technology use. Brazil J Psychiatry. (2020). 10.1590/1516-4446-2020-0870. [Epub ahead of print]. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 44. Chen Q, Hu Y. Users' self-awareness in TikTok's viewing context. J Res. (2020) 169:79–96. (Citation has been translated from Chinese language.) [ Google Scholar ]

- 45. Marengo D, Sindermann C, Elhai JD, Montag C. One social media company to rule them all: associations between use of Facebook-owned social media platforms, sociodemographic characteristics, and the big five personality traits. Front. Psychol. (2020) 11:936. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00936 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 46. Montag C, Błaszkiewicz K, Sariyska R, Lachmann B, Andone I, Trendafilov B, et al. Smartphone usage in the 21st century: who is active on WhatsApp? BMC Res Notes. (2015) 8:331. 10.1186/s13104-015-1280-z [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 47. Lu X, Lu Z, Liu C. Exploring TikTok use and non-use practices and experiences in China. In: Meiselwitz G, editor. Social Computing and Social Media. Participation, User Experience, Consumer Experience, and Applications of Social Computing. Springer International Publishing; (2020).p. 57–70. 10.1007/978-3-030-49576-3_5 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 48. Gu X. College students' short videos production and dissemination in the we-media era. J Anshan Nor Univer. (2020) 22:60–62. (Citation has been translated from Chinese language.) [ Google Scholar ]

- 49. Peterka-Bonetta J, Sindermann C, Elhai JD, Montag C. How objectively measured twitter and instagram use relate to self-reported personality and tendencies towards internet use/smartphone use disorder. Hum Behav Emer Technol. (2021). 10.1002/hbe2.243. [Epub ahead of print]. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 50. Kross E, Verduyn P, Sheppes G, Costello CK, Jonides J, Ybarra O. Social media and well-being: Pitfalls, progress, next steps. Trends Cogn Sci. (2021) 25:55–66. 10.1016/j.tics.2020.10.005 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 51. Kumar VD, Prabha MS. Getting glued to TikTok® – Undermining the psychology behind widespread inclination toward dub-mashed videos. Arch Mental Health. (2019) 20:76. 10.4103/AMH.AMH_7_19 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 52. Palupi ND, Meifilina A, Harumike YDN. The effect of using Tiktok applications on self-confidence levels. J Stud Acad Res. (2020) 5:66–74. 10.35457/josar.v5i2.1151 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 53. Wang J, Li H. Reflections on the popularity of Tiktok on University Campus and behavioral guidance. Soc Sci J. (2020) 32:60–64. (Citation has been translated from Chinese language.) [ Google Scholar ]

- 54. Billieux J, Schimmenti A, Khazaal Y, Maurage P, Heeren A. Are we overpathologizing everyday life? A tenable blueprint for behavioral addiction research. J Behav Addic. (2015) 4:119–23. 10.1556/2006.4.2015.009 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 55. Montag C, Hegelich S, Sindermann C, Rozgonjuk D, Marengo D. On corporate responsibility when studying social-media-use and well-being. Trends Cogn Sci. (2021). 10.1016/j.tics.2021.01.002 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 56. Montag C, Becker B, Gan C. The multipurpose application WeChat: a review on recent research. Front Psychol. (2018) 9:2247. 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02247 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 57. Bhandari A, Bimo S. Tiktok And The “Algorithmized Self”: A New Model Of Online Interaction. AoIR Selected Papers of Internet Research. (2020). 10.5210/spir.v2020i0.11172. Available online at: https://journals.uic.edu/ojs/index.php/spir/article/view/11172 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 58. Rozgonjuk D, Sindermann C, Elhai JD, Montag C. Comparing smartphone, WhatsApp, Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat: which platform elicits the greatest use disorder symptoms? Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. (2020). 10.1089/cyber.2020.0156. [Epub ahead of print]. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 59. Carbonell X, Panova T. A critical consideration of social networking sites' addiction potential. Addic Res Theor. (2017) 25:48–57. 10.1080/16066359.2016.1197915 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 60. Montag C, Wegmann E, Sariyska R, Demetrovics Z, Brand M. How to overcome taxonomical problems in the study of Internet use disorders and what to do with “smartphone addiction”? J Behav Addic. (2021) 9:908–14. 10.1556/2006.8.2019.59 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 61. Schivinski B, Brzozowska-Wo,ś M, Stansbury E, Satel J, Montag C, Pontes HM. Exploring the role of social media use motives, psychological well-being, self-esteem, and affect in problematic social media use. Front Psychol. (2020) 11:617140. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.617140 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 62. Bos AER, Muris P, Mulkens S, Schaalma HP. Changing self-esteem in children and adolescents: a roadmap for future interventions. J Psychol. (2006) 62:26–33. 10.1007/BF030610489866079 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 63. Best P, Manktelow R, Taylor B. Online communication, social media and adolescent wellbeing: A systematic narrative review. Child Youth Serv Rev. (2014) 41:27–36. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.03.001 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (472.3 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Advance Articles

- Editors Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Author Resources

- Read & Publish

- Reasons to Publish With Us

- Call For Papers

- About Postgraduate Medical Journal

- About the Fellowship of Postgraduate Medicine

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

- < Previous

Exploring TikTok to increase one’s health literacy: the Philippine experience

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Dalmacito A Cordero, Exploring TikTok to increase one’s health literacy: the Philippine experience, Postgraduate Medical Journal , Volume 100, Issue 1188, October 2024, Pages 776–777, https://doi.org/10.1093/postmj/qgae044

- Permissions Icon Permissions

I read with interest the recent article published in this journal regarding the emergence of medical TikTok videos, which are popularly becoming a medium for health information by the public. Through qualitative analysis, the authors rightfully emphasized the importance of the accessibility of quality information on the platform [ 1]. I fully support this call, especially given that limited health literacy (HL) remains a serious problem in many developing countries, like the Philippines. The rise and utilization of social media, with TikTok as one of the most popular apps, can be pointed out as one of the reasons for having a limited or high level of HL. Thus, I aim to flesh this claim by highlighting the effects of TikTok health videos on the HL of many Filipinos.

HL is the ability of individuals to gain access to, understand, and use information in ways that promote and maintain good health for themselves, their families, and their communities [ 2]. While developing countries often face pressing issues such as inadequate health care, a less obvious but equally threatening problem is low HL rates. It is linked to inadequate education and health systems because these structures relay health information to the general public. Thus, nations that lack these proper systems are more likely to have insufficient health education levels [ 3]. In the Philippines, the National Health Literacy Survey reports that among 2303 locals, 51.5% have limited HL [ 4]. This low level of HL is one of the reasons for the quick spread of the virus during the pandemic since there were many violations of the minimum health protocols set by the government. In the same way, because of poor HL, fake news found its way and seriously affected public health because many locals believed and accepted such unverified health information. The Philippines has been called the world’s social media capital because of its extraordinarily high usage time of about three hours daily. It was estimated that by 2029, over 95 million Filipinos will become social network users [ 5]. Many Filipinos are hooked to social media platforms for educational, entertainment, and other purposes.

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Short-term Access

To purchase short-term access, please sign in to your personal account above.

Don't already have a personal account? Register

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| April 2024 | 25 |

| May 2024 | 2 |

| June 2024 | 5 |

| July 2024 | 5 |

| August 2024 | 7 |

| September 2024 | 11 |

| October 2024 | 11 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- X (formerly Twitter)

- Recommend to Your Librarian

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1469-0756

- Print ISSN 0032-5473

- Copyright © 2024 Fellowship of Postgraduate Medicine

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

IEEE Account

- Change Username/Password

- Update Address

Purchase Details

- Payment Options

- Order History

- View Purchased Documents

Profile Information

- Communications Preferences

- Profession and Education

- Technical Interests

- US & Canada: +1 800 678 4333

- Worldwide: +1 732 981 0060

- Contact & Support

- About IEEE Xplore

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- Nondiscrimination Policy

- Privacy & Opting Out of Cookies

A not-for-profit organization, IEEE is the world's largest technical professional organization dedicated to advancing technology for the benefit of humanity. © Copyright 2024 IEEE - All rights reserved. Use of this web site signifies your agreement to the terms and conditions.

COMMENTS

This research paper conducts a literature review to investigate various forms of toxicity on social media, encompassing cyberbullying, hate speech, threats, and more. Specifically ...

This research investigates the effects of TikTok, a popular social content platform, on the academic productivity of Grade 11 STEM students at Cebu Doctors' University.

A recent paper by Bucknell Bossen and Kottasz (31) provided insight that, in particular, gratification of entertainment/affective needs was the most relevant driver to understand a range of behaviors on TikTok, including passive consumption of content, but also creating content and interacting with others.

The study results indicate that several TikTok research clusters exist, which summarize important topics such as the platform's overall impact on society, politics, culture, as well as human-centric issues such as social attachment, functional tics, and their implications for public health.

An empirical gap was observed concerning published scholarly works conducted focusing on the relationship and direct effect of TikTok utilization on students' engagement. Therefore, conducting an...

PDF | The emergence of the TikTok application represents noteworthy phenomenon in the realm of social media. It became an avenue for self-expression,... | Find, read and cite all the research...

Table 1 shows the level of influence of TikTok on SNSU students based on content, video quality, and music. The result shows that TikTok is very influential to the students with (a 2.83 average mean and .64 SD. The content got (2.85 mean and .64 SD), while Video quality got (2.83 mean and .66 SD).

In a recent study, TikTok became one of the vehicles for spreading COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among many Filipinos through their negative comments about fear and mistrust of the vaccine, misinformation and disinformation, and adamant attitude to vaccination [8].

This research aims to analyze and understand the determinants of the success of influencer marketing on TikTok, a leading social media platform among the young, and to provide practical guidelines to influencers and companies that want to take advantage of this opportunity.

Although influencer marketing through TikTok may deem beneficial, studies on how influencers create value for SMEs specifically in the context of a developing country like the Philippines are still scarce.