21 Multimedia Examples

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

Multimedia refers to media that combine multiple means of communication. Elements that could be combined include images, text, sound, animation, video, and even interactive elements.

The rise of multimedia in the past 70 years has helped us to develop more engaging and entertaining texts across mediums such as television and virtual reality.

And in the digital era, we’re increasingly capable of using interactive multimedia, allowing people to ‘choose their own adventure’ and give immediate feedback that can help shape their media experience.

But we can also reflect on very old forms of multimedia, such as plays, dance, and theater, where body language, costumes, and spoken scripts have combined to create immersive experiences.

Multimedia Examples

1. television.

Modes of Communication: Image, Video, Audio, Text

Television represents one of the earliest and most significant uses of multimedia.

It involves the amalgamation of audio and visual content, which surely would have been ground-breaking when it first came out, replacing radio as the premium medium of communications.

TV brought to viewers’ homes a wide array of programming, from news bulletins to sitcoms, documentaries, and movies. Different graphical elements like subtitles and closed captions also add to the multimedia integration, providing more accessibility to TV content.

Television’s use of multimedia has significantly influenced how information and entertainment are disseminated and received.

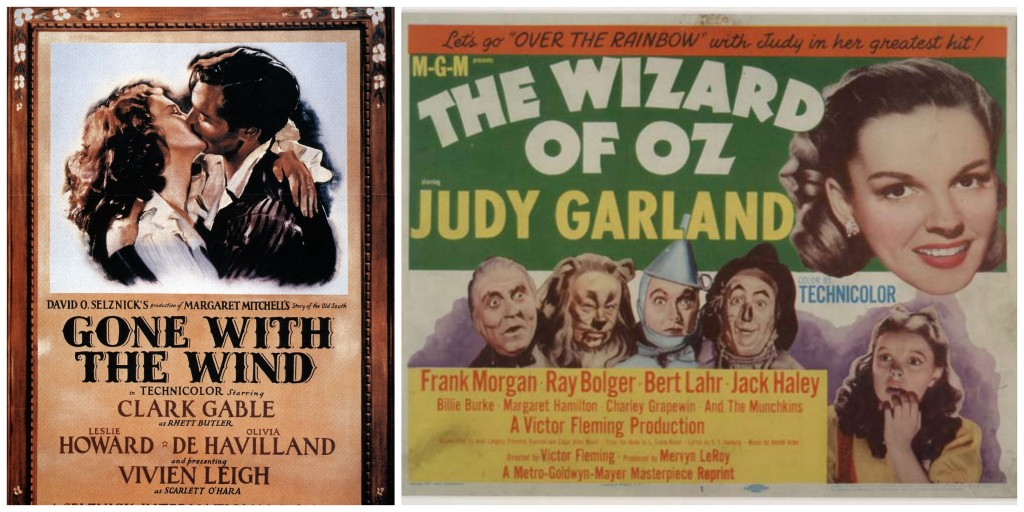

Cinema takes multimedia to another dimension, combining powerful audio and rich, high-definition visuals to narrate stories.

The multimodality of cinema started in the early 1900, with silent black-and-white films, where the second medium was often someone playing the piano in the theater.

Cinema has innovatively adopted technology to add sound, color, and eventually 3D imaging to its toolkit. Sound effects and music supplement dialogue and visual cues, shaping the mood and pacing of the narrative.

Combined, these elements engross audiences in a uniquely stimulating experience, embodying the essence of multimedia storytelling.

3. Video Games

Modes of Communication: Image, Video, Audio, Interactive, Text

Video games are a prime example of modern multimedia, leveraging text, images, sound, and interactive components to create captivating virtual, often 3D, worlds.

Brief text instructions often guide gameplay, while the on-screen graphics design the game’s aesthetics and dynamics. Soundtracks and sound effects add another layer of interaction, enhancing the atmospheric immersion.

Moreover, feedback systems and communication tools allow players to interact with the game and each other, sculpting video games into a comprehensive multimedia platform.

4. Interactive Websites

Interactive websites, like the one you’re on right now, marry text, images, audio, video, and interactive elements to offer a dynamic user interface.

Text serves to provide information, while images and videos supplement and illustrate this data in another format. Some websites will also utilize audio components for better communication and user interaction, such as by embedding a YouTube video.

The user’s inputs and clicks trigger responses from the site, such as opening a new page, showing a pop-up, or playing a video, substantiating the interactive aspect of the medium.

5. E-Learning Platforms

E-Learning platforms have brought learning to the digital-multimodal era , allowing users to engage with educational material through text, videos, and interactive quizzes online.

On these apps, text provides background knowledge for learners, while videos usually supplement this information with visual explanations.

When it comes to assessment, interactive quizzes are designed for users to test their understanding of the material instantly, offering a comprehensive, interactive learning experience.

Furthermore, such platforms often adjust (making the content easier and harder) depending on how well students have answered the questions, helping them to learn as effectively as possible.

6. Virtual Reality Games

Virtual Reality (VR) games provide an immersive multimedia experience using a combination of visuals, audio, and haptic feedback.

These games transpose players into a digital landscape where they can interact with the environment and objects within it, in real-time, using VR equipment.

Simultaneously, the audio elements conceive an aural ambiance that bolsters the overall gaming experience, heightening the emotive depth augmented by the game.

Consequently, Virtual Reality games offer an elaborate multisensory engagement, thereby pushing the frontiers of multimedia application in gaming.

7. Graphic Novels

Modes of Communication: Image, Text

Graphic novels have been around for over 100 years, and demonstrate the power of incorporating both text and visuals in storytelling – which is especially engaging for children.

Full-color panels of artwork illustrate the narrative and convey emotions, while the dialogue and captions in the text provide context and drive the plot.

Through the synergy of text and images, graphic novels offer an immersive reading experience that captivates readers by visually transporting them into the world of the story.

8. Interactive Kiosks

Modes of Communication: Image, Video, Audio, Interactive, Haptics, Text

Interactive kiosks at museums and trade shows have helped bring multimedia texts to traditional spaces.

These kiosks present users with both auditory and visual information through videos, images, and audio narration.

To add an interactive element, they often include touch screens or buttons that allow users to navigate the content at their own pace. This combination offers an engaging, user-friendly information delivery system that is accessible to a vast array of audiences.

9. Digital Marketing Ads

Digital marketing ads, such as those that you may see on this page right now, are demonstrate how multimedia is leveraged in the advertising industry to catch people’s attention and drive sales.

A succinct, yet powerful combination of text, audio, and video elements are employed by skilled advertising professionals to convey a brand’s message and sell products.

The text component often detail the benefits of a product or service, while embellishing pictures and videos visually depict these advantages, making them easier for potential customers to see themselves using the products. Paired with compelling audio – usually music or voice-over – these ads aim to build a strong emotional connection with the viewer, encouraging a subsequent conversion.

10. Mobile Apps

Mobile apps are at the forefront of multimedia use in this century. They usually combine text, images, videos, and sometimes also include interactive features.

For example, a fitness app might use text to describe a workout routine, videos to show the correct way to perform each exercise, and audio to provide motivational music or feedback during the workout.

The interactive features of such applications could include input fields for recording progress, thereby making them a perfect example of how various forms of media can be integrated to offer an engaging and convenient user interface.

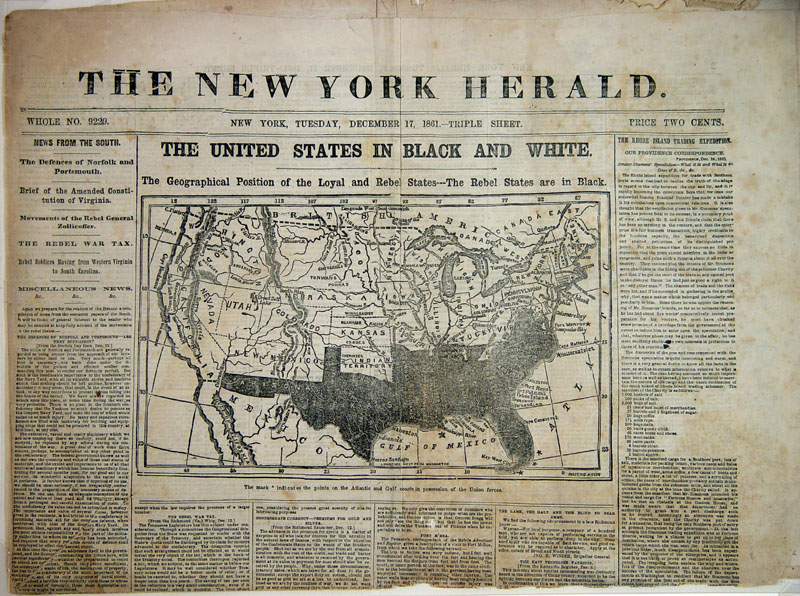

11. Online Newspapers

Online newspapers mark a significant advancement in the media industry, leveraging multimedia to present news in a more captivating manner.

Articles are typically written in text format and supplemented with photographs or infographics for visual emphasis. Video and audio recordings are often embedded to provide first-hand information and a degree of authenticity, as well as to enhance the user’s information-gathering experience.

Furthermore, online newspapers often include interactive elements such as polls, quizzes, and comment sections that encourage reader participation.

12. Music Streaming Platforms

Modes of Communication: Video, Audio

Music streaming platforms have increasingly embraced multimedia in recent decades. Besides audio content, these platforms often feature album art images, lyrics displayed in sync with the music, and artist bios or related news articles for additional context.

User engagement is also elevated with features like customization of playlists, sharing of favorite songs, and the inclusion of video content for certain tracks.

The conglomerate of these multimedia elements allows for a holistic music experience catered to variegated user preferences.

13. Social Media Platforms

Social media platforms significantly utilize multimedia to facilitate interaction, engagement, and content creation.

They incorporate text, images, video, and audio features, allowing users to consume and create diverse content.

For instance, an Instagram post can have a photo or video with a caption, hashtags, and an option for other viewers to leave comments. Instagram stories, further engage users with interactive features such as polls, music tracks, and question boxes.

This sort of integration of multiple media formats helps maintain user interest and promotes active participation.

14. Webinars

Primarily video-based, webinars offer real-time, interactive presentations, workshops, or lectures over the internet.

Text aids, such as subtitles or on-screen prompts, often complement the verbal communication .

Additionally, interactive elements like polls, Q&A sessions, and live chats provide an interactive platform for audience engagement, thus enhancing the learning or discussion experience.

The combination of these different media forms ensures Webinars are informative, engaging, and broadly accessible.

15. Digital Signage

Modes of Communication: Image, Video, Text

Digital signage is far more catchy and engaging than the old static boards that used to line highways.

The digitization of signs revolutionized advertising and public information, making them more catchy and engaging.

Typically, they loop a series of images, videos, and text, providing broad flexibility in the type and variation of information presented. Sound might be employed depending on the location and objective of the signage.

Additionally, some signage incorporates interactive aspects, such as touch screens or gesture recognition, boosting user engagement.

From malls to airports, digital signage illustrates multimedia’s far-reaching impact in the public domain.

16. Video Conferencing Tools

Video conferencing tools incorporate multimedia formats to enable real-time interaction amongst remote parties.

They utilize video and audio elements for direct communication, establishing a virtual meeting environment that closely parallels a physical setting.

Textual components can be integrated via chat boxes, screen sharing, and document sharing, while the interactive features, such as the raise-hand function or reactions, promote engaging and orderly discussions.

These tools exemplify how multimedia can effectively bridge physical distance and facilitate collaboration between dispersed teams.

17. Interactive Whiteboards

Modes of Communication: Image, Video, Audio, Interactive, Text, Haptics

Found primarily in classrooms and corporate meeting rooms, interactive whiteboards heavily leverage multimedia to boost collaboration and engagement.

They combine visuals, text, and audio through the presentation of information on a touch-sensitive screen. Users can write text digitally, draw diagrams, or display videos and images, while the interactive features allow for document editing, erasing, and moving elements around on the screen.

IWBs are excellent for teaching younger students, who can come up and touch the board, drag elements, and write on the board, to make learning more active.

18. In-Car GPS

In-Car GPS devices might not be your first form of multimedia that comes to mind, but the combination of the on-screen moving map and the instructions from the AI voice make it multimodal.

Textual elements are also used for listing road names or travel durations. The interactive feature allows drivers to input their desired destinations, thereafter, the dynamic map and real-time voice prompts guide them throughout the journey.

With multiple modes of communicating with the driver, an in-car GPS can help the driver to focus on the road while also receiving their information.

19. Karaoke Apps

Modes of Communication: Video, Text

Karaoke apps effortlessly integrate text, audio, and interactive features to provide a fun-filled musical experience.

They usually display song lyrics in text format timed to the melody, helping users sing along correctly.

The audio component is split into two parts: the instrumental background music and the vocal input from the user.

Some apps even include visual aids in the form of video lyrics or color-coded text to further guide singers. Users interact with the app not just by singing but also by selecting songs, adjusting settings, and sometimes even recording and sharing their performances.

20. Theater Performances

Modes of Communication: Image, Video, Audio, Interactive, Text, Physical Interaction

Theater performances, similar to cinema, couple visual and auditory components to weave narratives that captivate audiences.

This example demonstrates that multimodal communication is not as new as we might think – it existed before the digital age!

Theaters incorporate live actors, music, sound effects, props, and sometimes even projected visuals to transport audiences into their world.

Modern theaters may also employ digital elements such as LED screens or holographic technology to enhance the performance.

The immersive nature of these multilayered performances underscores how multimedia principles are not isolated within the digital sphere but are also thriving in traditional forms of communication and entertainment.

21. Virtual Tours

Virtual tours marry images, videos, audio, and oftentimes interactive elements to deliver an immersive exploration experience right in the comfort of your home.

Through a series of panoramic images or videos, viewers can visually ‘walk through’ various spaces, be it a real estate property, museum, or even world heritage site.

Audio guides and textual descriptions may provide additional context or narrate interesting stories about the places being toured.

Further, the interactive element lies in the ability to click or tap for advancing through spaces, zoom in on details, or rotate views, enabling a custom exploration experience. Virtual tours exemplify how multimedia can significantly enhance remote accessibility and exploration.

Before you Go

If you’re studying how to analyze the messages in multimodal texts, I’ve got a range of study guides that could help. Check them out below:

- How to do a Media Analysis

- How to do a Content Analysis

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 101 Hidden Talents Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

What’s Next? How Digital Media Shapes Our Society

By John McDonald

September 1, 2021

A summary of Professor Leah A. Lievrouw’s most recent book, which explores the rapidly changing role communication plays at the center of human experience and endeavor.

UCLA Information Studies Professor Leah A. Lievrouw’s first academic job was at Rutgers University in the late 1980s. One day, a colleague, a media effects researcher, was talking with her in her office and said, “Well, you know this new media stuff, it’s kind of interesting, but really it’s just a fad, isn’t it?”

That “new media stuff” has been the centerpiece of Lievrouw’s research ever since and today is central to many of the economic, social, political and policy challenges that confront the globe.

“My interest is in new technologies, communication information technologies and social change, and how change happens for good and ill. It’s really a sociological take. I’m more interested in what’s going on at the whole society or whole community level,” Lievrouw said. Professor Lievrouw joined the UCLA Department of Information Studies in 1995 and in 2005 co-edited “The Handbook of New Media” (Sage Publications), with Sonia Livingston of the London School of Economics. The book became a central resource for study of the field and is still used in classrooms and cited in research.

“It was really a big comprehensive survey with leading people in the field who were working on this research, right across various sub-fields and different topics,” Lievrouw said. “For a long time and in some circles still it is kind of the definitive capture of what the field was like and what the issues were at the moment.”

With changes in technology and communication rapidly occurring with ever larger impact, Lievrouw and her colleagues began talking about not just an update, but a whole new book.

Lievrouw decided to move forward and eventually linked up with Brian Loader, a professor at the University of York in the United Kingdom and editor-in-chief of the journal Information, Communication and Society, to serve as co-editor.

The book draws together the work of scholars from across the globe to examine the forces that shape our digital social lives and further our understanding of the sociocultural impact of digital media.

Routledge Handbook of Digital Media and Communication

“As of this writing, as the world undergoes breakdowns in social, institutional, and technological systems across every domain of human affairs in the wake of a biological and public health crisis of unprecedented scale and scope, such a framework for understanding communicative action, technology, and social forms has never been so apt or so urgently needed.” – Routledge Publishing

Mirroring the approach of the earlier “Handbook of Social Media,” the book is organized into a three-part framework exploring the artifacts or devices, the practices and institutional arrangements that are central to digital media, and draws the connections across the three elements.

The book explores topics such as the power of algorithms, digital currency, gaming culture, surveillance, social networking, and connective mobilization. As described in the introduction by Routledge, the “Handbook delivers a comprehensive, authoritative overview of the state of new media scholarship and its most important future directions that will shape and animate current debates.”

“I really like that again this seems to be a pretty definitive state-of-the-art kind of look at what is going on with these technologies,” Lievrouw said. “This has perhaps a more critical edge than we had 20 years ago, because we have begun to see the downsides of digital media as well as all the upsides that everyone had such hopes about. What makes me really happy is that this volume kind of pulls back a bit and takes a bigger stock of the issues and challenges. We have a few chapters that I think are just really definitive, written by some of the very best people on the planet. We were very lucky to recruit such a terrific lineup of people.”

Professor Lievrouw refers to a series of essays on critical topics in the book by leading experts such as Paul Dourish exploring Ubiquity or the everywhereness of digital media; Veronica Barrasi, writing about youth, algorithms, and political data; and Julie Cohen, writing about the nature of property in a world driven by social media and more.

“In her chapter, Cohen asks, what’s the nature of property? Every aspect of our behavior or of our beliefs is constantly kind of being pulled away from us, appropriated and owned by outfits like Google and like Facebook. They now consider this their proprietary information, and we’ve not had that before in the world really, certainly not on this scale. I think that’s worth exploring,” Lievrouw said.

Timing is everything, and the new book is emerging at a time of particular relevance and questioning about digital media.

“The book has happened to come out at a moment when there’s so much skepticism, and so much worry,” Professor Lievrouw said. “What’s interesting is that the worry is in the scholarly community too and has been for a little while.

“We’re in that moment where we are having to look, not only at the most egregious and outrageous behaviors, opinions, and disinformation, and all the kinds of things that have come out from under the rocks. And the system itself is rather mature at this point, so the question becomes, ‘Where is it going to go? What do we do next? Is it just more incursion, more data, more surveillance, more circulation of stuff?’ And we are doing it without editing, without gatekeepers. And we should never forget about the impact of places like Facebook, Google, Amazon. “It has changed social structure.

It has changed cultural practices. It has changed our perception of the world fundamentally. And I think it’s not just the technology that did this, it’s the way we built it.

“I think we are entering a period of reckoning about these technologies, the whole complex of people involved in the building and operation of platforms and different kinds of applications, especially data gathering. Data has come to the center of the economics of this thing in a way that it hasn’t before. This is a good moment to reassess what works, what has been emancipatory, what has been enabling for people, how the diffusion of these technologies, and the adaptation of their use, is impacting different places and different cultures all over the world.

“Every thoughtful researcher in this area I know is turning this over in their head, saying, ‘How did we get to this point? What happened here?’ I think what this book can help us understand not only where we are right now, but also to think about what could be next, and what can we do to repair this. Right now, I don’t think anybody has a solid answer for that. If they do, it’s an answer they don’t like.”

Excerpt from Introduction

No longer new, digital media and communication technologies—and their associated infrastructures, practices, and cultural forms—have become woven into the very social fabric of contemporary human life. Despite the cautiously optimistic accounts of the potential of the Internet to foster stronger democratic governance, enable connective forms of mobilization, stimulate social capital (community, social, or crisis informatics), restructure education and learning, support remote health care, or facilitate networked flexible organization, the actual development of digital media and communication has been far more problematic. Indeed, recent commentary has been more pessimistic about the disruptive impact of digital media and communication upon our everyday lives. The promise of personal emancipation and free access to unlimited digital resources has, some argue, led us to sleepwalk into a world of unremitting surveillance, gross disparities in wealth, precarious employment opportunities, a deepening crisis in democracy, and an opaque global network of financial channels and transnational corporations with unaccountable monopoly power.

A critical appraisal of the current state of play of the digital world is thus timely, indeed overdue, and required if we are to examine these assertions and concerns clearly. There is no preordained technological pathway that digital media must follow or are following. A measure of these changes is the inadequacy of many familiar concepts— such as commons, public sphere, social capital, class, and others—to capture contemporary power relations or to explain transitions from “mass society” to networked sociality—or from mass to personalized consumption. Even the strategies of resistance to these transitions draw upon traditional appeals to unionization, democratic accountability, mass mobilization, state regulation, and the like, all part of the legacy of earlier capitalist and political forms.

How then to examine the current digitalscape? Internet-based and data-driven systems, applications, platforms, and affordances now play a pivotal role in every domain of social life. Under the rubric of new media research, computer-mediated communication, social media or Internet studies, media sociology, or media anthropology, research and scholarship in the area have moved from the fringe to the theoretical and empirical center of many disciplines, spawning a whole generation of new journals and publishers’ lists. Within communication research and scholarship itself, digital technologies and their consequences have become central topics in every area of the discipline—indeed, they have helped blur some of the most enduring boundaries dividing many of the field’s traditional specializations. Meanwhile, the ubiquity, adaptability, responsiveness, and networked structure of online communication, the advantages of which—participation, convenience, engagement, connectedness, community—were often celebrated in earlier studies, have also introduced troubling new risks, including pervasive surveillance, monopolization, vigilantism, cyberwar, worker displacement, intolerance, disinformation, and social separatism.

Technology infrastructure has several defining features that make it a distinctive object of study. Infrastructures are embedded; transparent (support tasks invisibly); have reach or scope beyond a single context; learned as part of membership in a social or cultural group; are linked to existing practices and routines; embody standards; are built on an existing, installed base; and, perhaps most critically, ordinarily become “visible” or apparent to users only when they break down: when “the server is down, the bridge washes out, there is a power blackout.” As of this writing, as the world undergoes breakdowns in social, institutional, and technological systems across every domain of human affairs in the wake of a biological and public health crisis of unprecedented scale and scope, such a framework for understanding communicative action, technology, and social forms has never been so apt or so urgently needed.

Two cross-cutting themes had come to characterize the quality and processes of mediated communication over the prior two decades. The first is a broad shift from the mass and toward the network as the defining structure and dominant logic of communication technologies, systems, relations, and practices; the second is the growing enclosure of those technologies, relations, and practices by private ownership and state security interests. These two features of digital media and communication have joined to create socio-technical conditions for communication today that would have been unrecognizable even to early new media scholars of the 1970s and 1980s, to say nothing of the communication researchers before them specializing in classical media effects research, political economy of media, interpersonal and group process, political communication, global/comparative communication research, or organizational communication, for example.

This collection of essays reveals an extraordinarily faceted, nuanced picture of communication and communication studies, today. For example, the opening part, “Artifacts,” richly portrays the infrastructural qualities of digital media tools and systems. Stephen C. Slota, Aubrey Slaughter, and Geoffrey C. Bowker’s piece on “occult” infrastructures of communication expands and elaborates on the infrastructure studies perspective. Paul Dourish provides an incisive discussion on the nature and meaning of ubiquity for designers and users of digital systems. Essays on big data and algorithms (Taina Bucher), mobile devices and communicative gestures (Lee Humphreys and Larissa Hjorth), digital embodiment and financial infrastructures (Kaitlyn Wauthier and Radhika Gajjala), interfaces and affordances (Matt Ratto, Curtis McCord, Dawn Walker, and Gabby Resch), hacking (Finn Brunton), and digital records and memory (David Beer) demonstrate how computation and data generation/capture have transfigured both the material features and the human experience of engagement with media technologies and systems. The second part, “Practices,” shifts focus from devices, tools, and systems to the communicative practices of the people who use them. Digital media and communication today have fostered what some writers have called datafication—capturing and rendering all aspects of communicative action, expression, and meaning into quantified data that are often traded in markets and used to make countless decisions about, and to intercede in, people’s experiences. Systems that allow people to make and share meaning are also configured by private-sector firms and state security actors to capture and enclose human communication and information.

This dynamic is played out in routine monitoring and surveillance (an essay by Mark Andrejevic), in the construction and practice of personal identity (Mary Chayko), in family routines and relationships (Nancy Jennings), in political participation (Brian Loader and Veronica Barassi), in our closest relationships and sociality (Irina Shklovski), in education and new literacies (Antero Garcia), in the increasing precarity of “information work” (Leah Lievrouw and Brittany Paris), and in what Walter Lippmann famously called the “picture of reality” portrayed in the news (Stuart Allan, Chris Peters, and Holly Steel). Many suggest that the erosion of boundaries between public and private, true and false, and ourselves and others is increasingly taken for granted, with mediated communication as likely to create a destabilizing, chronic sense of disruption and displacement as it is to promote deliberation, cohesion, or solidarities.

The broader social, organizational, and institutional arrangements that shape and regulate the tools and the practices of digital communication and information, and which themselves are continuously reformed, are explored in the third part. Nick Couldry starts with an overview of mediatization, the growing centrality of media in what he calls the “institutionalization of the social” and the establishment of social order, at every level from microscale interaction to the jockeying among nation-states. There are essays that present evidence of the instability, uncertainty, and delegitimation associated with digital media; reflections on globalization; a survey of governance and regulation; a revisitation of political economy; and the trenchant reconsideration of the notion of property. Elena Pavan and Donatella della Porta examine the role of digital media in social movements while Keith Hampton and Barry Wellman argue that digital technologies may, in fact, help reinforce people’s senses of community and belonging both online and offline. Shiv Ganesh and Cynthia Stohl show that while much past research was focused on the “fluidity” or formlessness of organization afforded by “digital ubiquity,” in fact contemporary organizing is a more subtle process comprising “opposing tendencies and human activities, of both form and formlessness.”

Taken together, the contributions present a complex, interwoven technical, social/cultural, and institutional fabric of society, which nonetheless seems to be showing signs of wear, or perhaps even breakdown in response to systemic environmental and institutional crises. As digital media and communication technologies have become routine, even banal—convenience, immediacy, connectedness—they are increasingly accompanied by a growing recognition of their negative externalities—monopoly and suppressed competition, ethical and leadership failures, and technological lock-in instead of genuine, path breaking innovation. The promise and possibility of new media and digitally mediated communication are increasingly tempered with sober assessments of risk, conflict, and exploitation.

This scenario may seem pessimistic, but perhaps one way to view the current state of digital media and communication studies is that it has matured, or reached a moment of consolidation, in which the visionary enthusiasms and forecasts of earlier decades have grown into a more developed or skeptical perspective. Digital media platforms and systems have diffused across the globe into cultural, political, and economic contexts and among diverse populations that often challenge the assumptions and expectations that were built into the early networks. The systems themselves, and their ownership and operations, have stabilized and become routinized, much as utilities and earlier media systems have done before, so they are more likely to resist root-and-branch change. They are as likely to reinforce and sustain patterns of knowledge and power as they are to “disrupt” them.

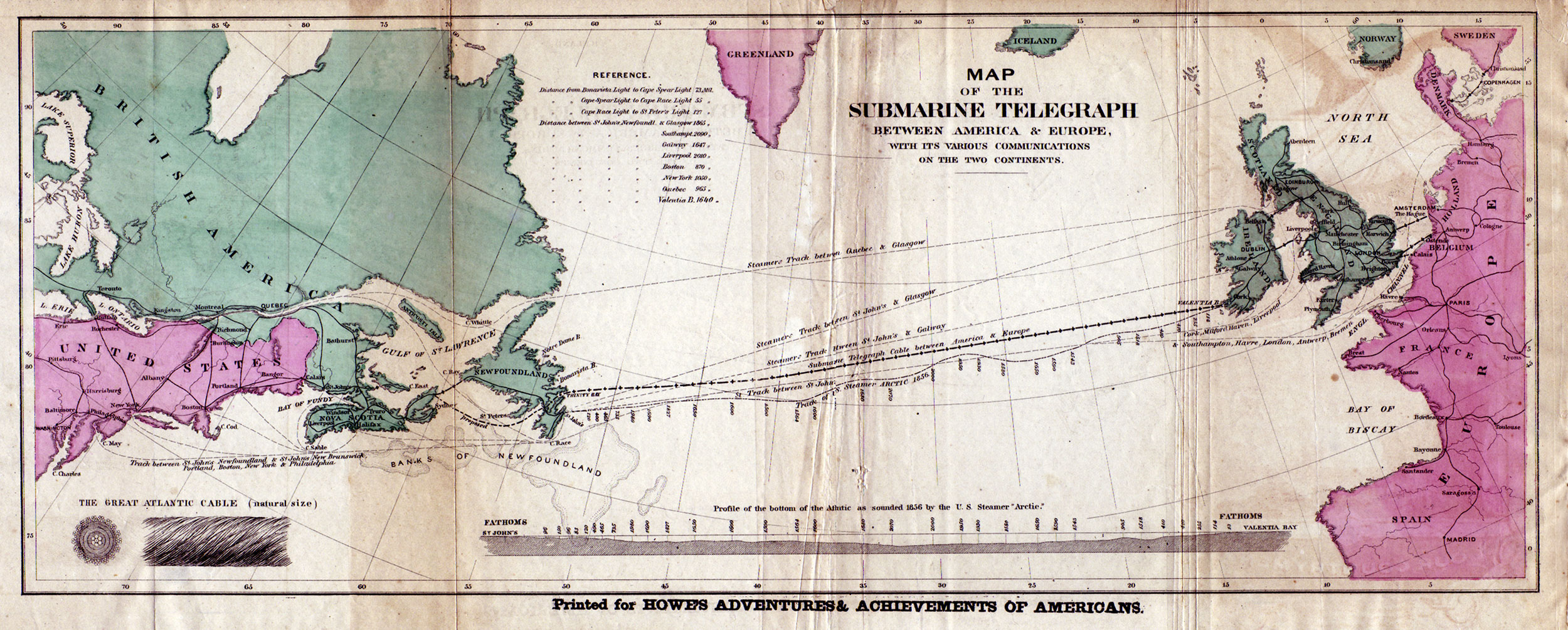

In another decade we might expect to find that the devices, practices, and institutional arrangements will have become even more integrated into common activities, places, and experiences, and culture will be unremarkable, embedded, woven into cultural practices, standardized, and invisible or transparent, just as satellite transmissions and undersea cables, or content streaming and social media platforms, are to us today. These socio-technical qualities will pose new kinds of challenges for communication researchers and scholars, but they also herald possibilities for a fuller, deeper understanding of the role communication plays at the center of human experience and endeavor.

This article is part of the UCLA Ed&IS Magazine Summer 2021 Issue. To read the full issue click here .

© 2024 Regents of the University of California

- Accessibility

- Report Misconduct

- Privacy & Terms of Use

Home — Essay Samples — Sociology — Social Media — Social Media Impact On Society

Social Media Impact on Society

- Categories: Social Media

About this sample

Words: 614 |

Published: Mar 13, 2024

Words: 614 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof Ernest (PhD)

Verified writer

- Expert in: Sociology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 479 words

5 pages / 2417 words

3 pages / 1526 words

2 pages / 825 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Social Media

Facebook is a social networking website that was founded by Mark Zuckerberg and his college roommates in 2004. It has since grown to become one of the most popular platforms for communication and sharing content online. The [...]

Social media has become an integral part of our daily lives, with millions of people around the world using platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter to connect, share, and engage. Whether it's posting updates about our [...]

In today's digital age, social media has become an integral part of college students' lives. With the prevalence of platforms such as Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, and TikTok, students are constantly connected and engaged with [...]

Social media has become an integral part of modern life, shaping the way we communicate, share information, and connect with others. However, the roots of social media can be traced back to ancient civilizations and have evolved [...]

Social media creates a dopamine-driven feedback loop to condition young adults to stay online, stripping them of important social skills and further keeping them on social media, leading them to feel socially isolated. Annotated [...]

Social media is a superb factor or a awful issue? That is the maximum often asked query these days. Nicely, there are constantly aspects of the entirety. It depends to your perspective on how you perceive it. The same goes for [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Role of Media in Society Essay

Introduction, overview of the role of media in society, works cited.

In today’s society, the flow of information among the citizenry plays an important role towards the development of an informed society. To this effect, the media has been instrumental in ensuring that the population gets current news and information on different issues affecting various societies.

Arguably, without the media, the world would consist of an ignorant population devoid of any relevant information relating to issues affecting their environment. With this in mind, it could be argued that the media provides the backdrop against which we make sense of any new conditions and information that we encounter in a world that is increasingly becoming globalized.

Since its conception, the media has been hugely influential in the development of the society. The media can be used to drive public opinion, report on current news and advance some social values. The media is at best a complex genre which may be broken down into a large number of sub-genres such as news stories, opinion columns, advertisements, sports and horoscopes to name but a few.

As such, the role of the media in today’s society is important because it essentially helps individuals get access to valuable information, educate the people in the communities and is a useful, affordable and an economical tool for entertainment.

In today’s society, the social issue that has particularly struck individuals through the decades is that of the media. In this study, the various opinions held in regard to the media and how it operates shall be provided. Through the analysis of relevant literature, a brief yet informative discussion of the various benefits that have been enjoyed as a result of the media shall be presented. This shall be done by highlighting key areas where the media has been instrumental.

These areas include but are not limited to: provision of information, a source of education and knowledge, link between members of the global community and a source of entertainment. The differing opinions propagated by media critics shall also be presented. This shall at the end help us understand the roles that the media plays in society as well as the extent to which the media has been successful in performing its duties.

As such, it shall be a worthwhile endeavor to shed some light on the benefits as well as the costs that have risen due to the presence and effects of the media in our societies. This analysis shall help in the provision of a clearer understanding on how the media affects society.

The media is arguably one of the most powerful agents for change and the betterment of society. Its role as the society’s eyes; indeed a ‘watchdog’ constantly monitoring and critiquing the actions of those in authority for the betterment of society are some of the attributes that previously made the media seem as a positive influence to society.

The ability of media to so accurately reflect the mood of the society and advocate for people to fight against social injustices and vices portrays the media as a tool for promoting justice, equality and harmony among the masses.

In regards to this statement, the current states of affairs indicate that societies are ridden with selfishness and actions aimed at advancing individual goals. This can be derived from the argument raised by Michael Meyers who claims that today’s media does not educate the audience but train them (Kramer, Meyers and Rothstein 582).

This he attributes to the fact that the media outlets no longer providing credible information. In this regard, the audience does not buy the truth, but what prominent figures want them to believe. The author is trying to bring out the fact that media is biased.

The proposed biasness has its root in the anti-intellectual and anti-democratic media. In addition, the media’s advertisement of products and services is an act aimed at enabling the consumers to make informed choices. As Bernt explains, the skills and artistic nature used to present persuasive advertisements help consumers relate products to their lifestyle and preferences (193).

Texts and images represented in advertisement can signify a myriad of meanings to the viewer. All this is in an attempt by the creator of the advert to persuade the consumer to think, feel or act in a predetermined manner (Bernt 194). Advertisement is therefore more of an educative venture than a deliberate attempt to sway the consumer in any predetermined direction since in the end; the consumers are better informed of the variety of brands that are at their disposal.

Bernt suggests that the heavy emphasis of advertisements in media is due to the fact that advertisers are the dominant sources of revenue for most modern media (193). The influence that advertisements have on the people is colossal as can be inferred from the rise in sales for corporations that engage in large-scale advertisement.

Bernt further asserts that the persuasive nature of advertisements has had a great effect on American culture in regards to the relationship between working hard and purchasing power (193). Bernt asserts that advertisements have “replaced Puritanism or the Protestant work ethic as the driving force in American society that causes people to work hard in order to shop even harder (193).”

The various forms of entertainment availed e.g. Movies, sports, interactive programs and Music productions are very important means of relieving stress after a long day at work. In addition, they help alleviate boredom. As such, the sole agenda of such products is recreational and providing means for people to enjoy themselves and connect (Bellah et al 67).

For example, through satellite television providers like DSTV people all over the world are able to enjoy the entertainment genre that best suit their preferences. Examples include movies, sports, music and news. Truth be told, football clubs would never have gained such a strong and wide fan base were it not for the media.

In regards to change in journalism, Pavlik highlights on how journalism has been affected by the transformation of the new media (Fernback 163).

In his opinion, new media technologies have greatly affected the traditional perspective of journalism. This he explains by expounding on the new journalistic trends such as changes in the contents provided to the audience as news, changes in how journalists work, structural changes in news organizations and changes that have occurred in the correlations between media outlets, journalists and different audiences (Fernback 163).

These changes brought about by new media technologies have to a large extent led to the contextualization of journalism; a situation whereby journalism has become less objective and practical.

On the same note, Palvik (as cited by Fernback 163) further notes that these new trends perceive journalists as interpreters of current events who in their efforts “empower the audience and reconnect communities (Fernback 163).”

According to Palvik, the new transformations being experienced in media outlets can be attributed to the availability and emergence of online infrastructure, high degree of customization, instantaneity and interactivity that characterize new media. In his point of view, Palvik believes that such developments will at the end make journalism a better tool to promote democracy (Fernback 163).

Evidence of such developments can be derived from the emergence of the internet and the online architecture that supports this vast source of information. Through online encyclopedias such as Wikipedia and the various search engines, people are able to access information and learn about different issues that affect their lives.

In addition, students in all academic fields are able to do more research in their designated fields and as a result, they become more knowledgeable in these areas than they would have been while using the traditional means of acquiring knowledge. Similarly, the internet has also provided people with a global means of communicating and learning about each other through websites like “facebook” and “twitter”.

People from different countries globally are able to interact and socialize in the comfort of their homes without the inconveniencies caused by travelling as well as the enormous costs that would have otherwise been incurred. These facts prove Palvik’s assertion that new media is at the forefront in empowering the masses (by providing useful information) and connecting communities (interactive nature of the internet, radio and TV talk shows e. t. c.).

On the other hand, Preston (as cited by Fernback 163) contends that the transformations being experienced in media are as a result of political, social, economical and communication patterns rather than technological developments.

Preston asserts that the interrelation that exists between social and informational sciences accompanied by non-academic and industrial literatures can be used by media so as to develop an equitable society and ensure social order (Fernback 163). In his book reshaping communication , Preston uses the aforementioned aspects to develop a model that explores the social role of information and communication in societies today (Fernback 163).

In his opinion, Preston argues that our cultural, informational and social bearings are hinged not on technological advancements, but on the socioeconomic, political and communication trends that we adapt (Fernback 164). In this regard, it can arguably be stated that the role of the media in society is not determined by technological advancements, but by the socio-technical paradigm (Fernback 164).

The positive view of the media has greatly been challenged with time. No longer do the various media outlets stand out as the ‘last front were nobility and idealism still had a foothold.’ Instead, the media just like any other business has been influenced by competition and ratings. As such, it has been noted for a fact that media outlets do at times express their own biased opinions which may not always be ideal or noble at that.

For example, Gay Talese attests to the fact that the New York Times editor Gerald Boyd refused to print a story about an interracial wedding simply because it never emphasized on Black victimization (Kramer, Meyers and Rothstein 575). According to Gay Talese, any story that would soften the perception people had on such issues was disallowed and could not be printed (Kramer, Meyers and Rothstein 575).

In this case, the Media’s actions which were previously perceived as being selfless and socially motivated have been exposed to not always have been driven by benevolence. These actions are at times resounded with self interests and personal gains for the media houses and the corporations that sponsor them.

The previous view of the media’s ability to correctly reflect on the society’s mood has also been greatly questioned as the media does at time appear to affect the set the society’s mood as opposed to reflecting it through the use of propaganda. (Kramer, Meyers and Rothstein suggest that the one of the media’s greatest power is in its ability to subtly influence our opinion (575).

They further assert that in events that elicit a lot of public opinion, propaganda plays a great role and polarizes people along lines that they may not necessarily have taken had they not been “persuaded” to do so.

This subtle psychological nudges can be used to further the cause of big corporations in the form of advertisements or by politicians who want to sway public opinions for their own good. To this effect, the people’s previous trust in the media report has therefore been greatly clouded by this realization.

In terms of the unbiased reporting which had for a long time been viewed to be the hallmark of the popular media, it has been noted that some media reports are actually aimed at making the recipient of the information form a certain pre-determined opinion thus destroying any illusion of un-biasness (Kramer, Meyers and Rothstein 575).

Media outlets can therefore set out to further some social cause which they believe in. Using the cultivation theory, Burton propose that exposure to some kinds of media often cultivate certain attitudes and values (Steffen 455). As an example, Steffen sheds some light on how Arab media has in the recent past adopted the western form of journalism and media presentation (455).

In this regard, the author states that even journalists from countries such as Egypt and other Arabic countries which has stringent media policies accept western media values such as accuracy and balance (Steffen 455). As such, the reporter’s opinions and attitude will rub on the general population thus coloring their view of some events.

In addition, the aforementioned assertion that advertisement aired in different media outlets is aimed at making the consumer better informed has been changed by evidence which strongly suggests that advertisements are aimed at actively influencing the decision that the consumer makes or may make in future (Steffen 456).

What this means is that advertisement is no longer a primary tool for marketing, instead, it has been used to combat the aggressive competition. To this effect, only the consumers suffer because the advertisements no longer help them make informed decisions about the products but instead, the advertisements influence their judgments by giving half-truths.

An especially troubling fact that revealed through various research efforts is that uncontrolled media in some instances leads to desensitization of the population on issues such as violence.

Continuous exposure to media violence especially on the young and impressionable segment of the population can lead to catastrophic results as has been witnessed before in the various random shootouts that occur in our schools. Research shows that media violence encourages aggressive behavior and leads to pessimism in children (Burton 123; Steffen 456).

This information contradicts the aforementioned perception of the media as a guardian and propagator of social values since the compelling evidence presented by research showed that media also leads to breaking of social values and leads to a disruption of harmony through the violence it encourages.

On the same note, rampant advertisements through media outlets have in the recent past characterized modern media. These advertisements aim at influencing the consumer to maintain or develop some form of ideology (Bernt 194). This close relationship that media and advertising have developed raises concerns over the influences that the media may be willing to wield so as to achieve the advertising objectives.

A closer observation of the movies and other entertainment forms presented by the media revealed heavy advertisements therein. These rampant acts of branding were previously unknown to many and their effect though unconsciously administered is substantial.

The media’s promotion of social values is also at times only used as a cover to influence consumers by use of advertisement (Fernback 164). Due to these advertisements, naive recipients of the information presented are unwittingly influenced into buying the products that the particular advertisements promote.

This is at best a very irresponsible behavior by the media since most people are favorably disposed to agree with sentiments that are projected by the media. These misuses of social issues as a marketing tool have also changed the positive role that the media was supposed to deliver. This is mainly due to the fact that the media is being used as a tool for furthering the objectives of corporations at the cost of an unsuspecting population.

The role played by the media in today’s society cannot be understated. However, caution should be taken because as expressed in this study, not all media is healthy. Through this research, the knowledge that has been transferred herein should not make the public skeptical of the media but should help them become more skeptical about the issues being addressed through various media outlets.

This will invariably transform them from being passive, unquestioning and all-believing recipients, to active and questioning recipients of the information which is provided by the media. Nevertheless, a free and vibrant media is necessary for the good of the society. An unfettered media is the hallmark of a truly unbiased society. However, one should adopt a more questioning stance when dealing with any information provided by the media.

Bellah, Robert. ET AL.”Community, Commitment, and Individuality.” Literacies: Reading, Writing, Interpretation. New York: W.W. Norton, 2000. 65-74. Print.

Bernt, Joseph. P. “Ads, Fads, and Consumer Culture: Advertising’s Impact on American Character and Society.” Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly 78.1 (2001): 193-194. Research Library, ProQuest. Web.

Fernback, Jan. “Journalism and New Media / Reshaping Communications: Technology, Information and Social Change.” Journalism & Mass Communication Educator 57.2 (2002): 162-164. Research Library, ProQuest. Web.

Kramer Hilton, Michael Meyers and Edward Rothstein. “The media and our country’s agenda.” Partisan Review 69.4 (2002): 574-606. Research Library, ProQuest. Web.

Steffen, Brian. J. “Media and Society: Critical Perspectives.” Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly 83.2 (2006): 455-456. Research Library, ProQuest. Web.

- Media and Celebrity Influence on Society

- The Impact of Media on Society

- The Web Site for Online Journalism

- Social Media Replacing Traditional Journalism

- Media and Communication in Journalism Firms

- New Advertising Campaign of Crocs Company

- The Corporation & Our Media, Not Theirs

- Guns, Germs and Steel

- Functions and Power of Mass Media: Views of Two German Authors

- Chicken Run and The Nightmare Before Christmas

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, July 11). Role of Media in Society. https://ivypanda.com/essays/role-of-media/

"Role of Media in Society." IvyPanda , 11 July 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/role-of-media/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'Role of Media in Society'. 11 July.

IvyPanda . 2018. "Role of Media in Society." July 11, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/role-of-media/.

1. IvyPanda . "Role of Media in Society." July 11, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/role-of-media/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Role of Media in Society." July 11, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/role-of-media/.

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers

Some functions, such as personalized recommendations, account preferences, or localization, may not work correctly without these technologies. For more details, please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy .

To enable personalized advertising (such as interest-based ads), we may share your data with our marketing and advertising partners using cookies and other technologies. These partners may have their own information collected about you. Turning off the personalized advertising setting won't stop you from seeing IvyPanda ads, but it may make the ads you see less relevant or more repetitive.

Personalized advertising may be considered a "sale" or "sharing" of the information under California and other state privacy laws, and you may have the right to opt out. Turning off personalized advertising allows you to exercise your right to opt out. Learn more in IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy .

Introductory essay

Written by the educators who created Covering World News, a brief look at the key facts, tough questions and big ideas in their field. Begin this TED Study with a fascinating read that gives context and clarity to the material.

At the newsstand, on our smartphones and while watching the evening news, we learn about faraway people and places from the journalists, stringers and correspondents who work for news agencies and other media outlets around the globe. Global news is everywhere — from the front page news read by a New Yorker on Madison Avenue to the government radio station broadcasting in Pyongyang.

However, it would be a mistake to consider this a completely new phenomenon or to overstate its pervasiveness. Many people tend to think that global news is both a recent phenomenon and one that we can credit to advances in technology. If we think of 'news' in terms of newspaper articles or television reporting, then news is only as old as the technologies of press and video, and dates back to the first newsletters that circulated in Europe in the 17th century.

But in reality, humans have shared information about current affairs within and across borders for thousands of years, starting with the news networks of the ancient Phoenicians. The historical record also describes merchants sharing political news along ancient trade routes, minstrels and other traveling artists whose fictional performances also carried information about social change, and criers in medieval town squares.

If news is not a product of modern technologies, it's nevertheless true that technological change has had a dramatic impact on how news is made and consumed: where once we had printed newsletters distributed twice a day, now we have Twitter feeds refreshed twice a minute, and carrying information from an ever-widening array of sources. We live, as media critics like Marshall McLuhan have argued, in a global village.

The trouble with this vision of 'global news' is that it's not nearly as complete as we imagine it to be. According to the World Bank, of the world's seven billion people, only 80% have access to electricity (or the gadgets like computer and televisions that depend on it), 75% have access to mobile phones, and a meager 35% to the Internet. Most people on the planet aren't connected to what we think of as the 'global media' at all. As Global Voices founder Ethan Zuckerman points out in his TED Talk, "There are parts of the world that are very, very well connected, [but] the world isn't even close to flat. It's extremely lumpy."

Just as critically, the content that makes up the 'global media' is still heavily focused on a few key centers of power. In her TED Talk, Public Radio International's Alisa Miller shares a powerful map of the news consumed by American audiences in 2008: most of it focused on the U.S., and to a lesser extent, on countries with which the U.S. has military ties. Ethan Zuckerman points out that this lack of global coverage is pervasive, whether it's at elite news outlets like The New York Times or on crowdsourced digital information platforms like Wikipedia.

Moreover, Zuckerman argues, it's not just about the stories that get made — it's about what stories we choose to listen to. Thirty years ago, Benedict Anderson made waves when he argued that political structures (like states) depend upon a set of shared values, the 'imagined community,' and that the media plays a key role in creating those values. Zuckerman, however, argues that in today's world the disconnect between what we imagine to be our community, and the community we actually live in, is a major source of global media inequality. We connect to the Internet, with its technological capacity to link up the whole world, and imagine that we live in a global village. But in practice, we spend most of our time reading news shared by our Facebook friends, whose lives and interests are close to our own. Zuckerman calls this 'imagined cosmopolitanism.'

Compounding the problem, the stories we do attend to can be heavily distorted, reducing whole countries or societies to a single stereotype or image. As author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie explains in her TED Talk about the 'single story,' when all the tales we hear about a country follow the same pattern, we begin to imagine that this pattern is all there is know. The 'single story' can affect all of us, rich and poor: Adichie talks of her own misconceptions about Nigeria's rural poor, of her surprise at encountering the diversity of life in Mexico, and of her college roommate's reductive vision of Africa as poor and underdeveloped. The difference, she argues, is that there are simply more stories out there about powerful countries than about less powerful ones, and that makes it harder for us to reduce those societies to 'single stories' in our minds.

What can we do?

First, we can tell different stories about the places that are prone to reduction. In her TED Talk, Yemeni newspaper editor Nadia Al-Sakkaf takes us to the Yemen she lives in — where terrorism and political upheaval are real problems, but far from the whole picture. Moreover, in her account, each image can tell many stories. A woman with a veiled face can represent the role of fundamentalist Islam in Yemeni society, but she argues that a look behind the veil shows us that many of these women are holding down jobs and earning income, and in so doing, changing their role within their own families and in Yemeni society more broadly.

Second, we can find ways to invest in journalism. As Alisa Miller argues, a major obstacle to a truly global news media is the cost of production, of keeping bureaus in every country and paying for journalists to produce deep, investigative stories. The great paradox of media economics in the digital age is that the Internet makes it possible for us to consume more content, but falling advertising revenues means that each piece of content must cost a little less to produce. That pushes news outlets, even wealthy ones, in the direction of gossip and regurgitated press releases that can be produced by a reporter who hasn't left her desk.

One way to break this cycle, Ethan Zuckerman argues, is to make small and targeted investments in local journalists in the developing world. He describes a blogger training program in Madagascar that became a newsroom overnight when world media outlets needed verified content from a country undergoing revolution. He highlights the critical work of professional curators like Amira Al Hussaini at Global Voices or Andy Carvin at the Associated Press.

At the heart of these recommendations is a shift in the way we understand the mission of journalists — or rather, a return to an old way of thinking about news.

Right up until the early 20th century, all journalists were assumed to be opinion writers. Reporters went places to report, made up their own minds about a topic, and wrote an account that included not only facts, but an argument for what position readers at home should take and what political actions might follow. George Orwell's colorful and opinionated essays from South East Asia, for example, were published as reportage.

Then the Cold War started, and in the democratic West, journalists began to strive for objective impartiality, to distinguish their work from the obvious, state-sponsored propaganda of the Soviet bloc. Many critics at the time questioned whether 'true' objectivity was possible, but no major western news organization disputed that it was the ideal.

Today, we're seeing a return to the older understanding of journalism, towards an acceptance that even independent reporting carries a viewpoint, shaped by the people who produce it. Moreover, contemporary journalists are increasingly coming to see this viewpoint as a strength rather than as a weakness, and using social media to be more transparent to readers about the values they bring to stories. New York University's Jay Rosen, for example, has argued powerfully that the 'view from nowhere' advocated by 20th century western reporters is dangerous because it can lead journalists to treat 'both sides' of a story equally even when one side is telling objective falsehoods or committing crimes.

Many of the speakers in Covering World News describe their journalism — whether it is Global Voices or the Yemen Times — as having an explicit moral and political mission to change our perceptions of under-covered regions of the world.

But no speaker is more passionate on this subject than TED speaker and photojournalist James Nachtwey, who credits the activist context of the 1960s for inspiring him to enter journalism, using photography to "channel anger" into a force for social change. Nachtwey's work has brought him, at times, into partnership with non-profit aid organizations, an alliance that is increasingly common in today's media world but would surely not have fit within the 'objective' media of a half-century ago. Nachtwey sees himself as a 'witness' whose place in the story is not to be invisible, but to channel his own humane outrage at war or social deprivation in order to drive social and political change: in one case, a story he produced prompted the creation of a non-profit organization to collect donations from readers.

This kind of work is a form of 'bridge building,' a theme that emerges in many of our talks. For while there may not be one 'global media' that includes all communities equally and reaches all parts of the globe, there are many individuals whose skills and backgrounds enable them to go between the connected and less connected pockets of the world, bridging gaps and contributing to mutual understanding. That, perhaps, is the way forward for international journalism.

Let's begin our study with Public Radio International CEO Alisa Miller, an ardent advocate for a global perspective in news programming. In her TEDTalk "The news about the news," Miller shares some eye-opening statistics about the quantity and quality of recent foreign reporting by American mainstream media organizations.

Alisa Miller

How the news distorts our worldview, relevant talks.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

The danger of a single story.

Ethan Zuckerman

Listening to global voices.

James Nachtwey

My wish: let my photographs bear witness.

Nadia Al-Sakkaf

See yemen through my eyes.

Suggestions or feedback?

MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Machine learning

- Sustainability

- Black holes

- Classes and programs

Departments

- Aeronautics and Astronautics

- Brain and Cognitive Sciences

- Architecture

- Political Science

- Mechanical Engineering

Centers, Labs, & Programs

- Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL)

- Picower Institute for Learning and Memory

- Lincoln Laboratory

- School of Architecture + Planning

- School of Engineering

- School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

- Sloan School of Management

- School of Science

- MIT Schwarzman College of Computing

Why social media has changed the world — and how to fix it

Press contact :, media download.

*Terms of Use:

Images for download on the MIT News office website are made available to non-commercial entities, press and the general public under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives license . You may not alter the images provided, other than to crop them to size. A credit line must be used when reproducing images; if one is not provided below, credit the images to "MIT."

Previous image Next image

Are you on social media a lot? When is the last time you checked Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram? Last night? Before breakfast? Five minutes ago?

If so, you are not alone — which is the point, of course. Humans are highly social creatures. Our brains have become wired to process social information, and we usually feel better when we are connected. Social media taps into this tendency.

“Human brains have essentially evolved because of sociality more than any other thing,” says Sinan Aral, an MIT professor and expert in information technology and marketing. “When you develop a population-scale technology that delivers social signals to the tune of trillions per day in real-time, the rise of social media isn’t unexpected. It’s like tossing a lit match into a pool of gasoline.”

The numbers make this clear. In 2005, about 7 percent of American adults used social media. But by 2017, 80 percent of American adults used Facebook alone. About 3.5 billion people on the planet, out of 7.7 billion, are active social media participants. Globally, during a typical day, people post 500 million tweets, share over 10 billion pieces of Facebook content, and watch over a billion hours of YouTube video.

As social media platforms have grown, though, the once-prevalent, gauzy utopian vision of online community has disappeared. Along with the benefits of easy connectivity and increased information, social media has also become a vehicle for disinformation and political attacks from beyond sovereign borders.

“Social media disrupts our elections, our economy, and our health,” says Aral, who is the David Austin Professor of Management at the MIT Sloan School of Management.

Now Aral has written a book about it. In “The Hype Machine,” published this month by Currency, a Random House imprint, Aral details why social media platforms have become so successful yet so problematic, and suggests ways to improve them.

As Aral notes, the book covers some of the same territory as “The Social Dilemma,” a documentary that is one of the most popular films on Netflix at the moment. But Aral’s book, as he puts it, "starts where ‘The Social Dilemma’ leaves off and goes one step further to ask: What can we do about it?”

“This machine exists in every facet of our lives,” Aral says. “And the question in the book is, what do we do? How do we achieve the promise of this machine and avoid the peril? We’re at a crossroads. What we do next is essential, so I want to equip people, policymakers, and platforms to help us achieve the good outcomes and avoid the bad outcomes.”

When “engagement” equals anger

“The Hype Machine” draws on Aral’s own research about social networks, as well as other findings, from the cognitive sciences, computer science, business, politics, and more. Researchers at the University of California at Los Angeles, for instance, have found that people obtain bigger hits of dopamine — the chemical in our brains highly bound up with motivation and reward — when their social media posts receive more likes.

At the same time, consider a 2018 MIT study by Soroush Vosoughi, an MIT PhD student and now an assistant professor of computer science at Dartmouth College; Deb Roy, MIT professor of media arts and sciences and executive director of the MIT Media Lab; and Aral, who has been studying social networking for 20 years. The three researchers found that on Twitter, from 2006 to 2017, false news stories were 70 percent more likely to be retweeted than true ones. Why? Most likely because false news has greater novelty value compared to the truth, and provokes stronger reactions — especially disgust and surprise.

In this light, the essential tension surrounding social media companies is that their platforms gain audiences and revenue when posts provoke strong emotional responses, often based on dubious content.

“This is a well-designed, well-thought-out machine that has objectives it maximizes,” Aral says. “The business models that run the social-media industrial complex have a lot to do with the outcomes we’re seeing — it’s an attention economy, and businesses want you engaged. How do they get engagement? Well, they give you little dopamine hits, and … get you riled up. That’s why I call it the hype machine. We know strong emotions get us engaged, so [that favors] anger and salacious content.”

From Russia to marketing

“The Hype Machine” explores both the political implications and business dimensions of social media in depth. Certainly social media is fertile terrain for misinformation campaigns. During the 2016 U.S. presidential election, Russia spread false information to at least 126 million people on Facebook and another 20 million people on Instagram (which Facebook owns), and was responsible for 10 million tweets. About 44 percent of adult Americans visited a false news source in the final weeks of the campaign.

“I think we need to be a lot more vigilant than we are,” says Aral.

We do not know if Russia’s efforts altered the outcome of the 2016 election, Aral says, though they may have been fairly effective. Curiously, it is not clear if the same is true of most U.S. corporate engagement efforts.

As Aral examines, digital advertising on most big U.S. online platforms is often wildly ineffective, with academic studies showing that the “lift” generated by ad campaigns — the extent to which they affect consumer action — has been overstated by a factor of hundreds, in some cases. Simply counting clicks on ads is not enough. Instead, online engagement tends to be more effective among new consumers, and when it is targeted well; in that sense, there is a parallel between good marketing and guerilla social media campaigns.

“The two questions I get asked the most these days,” Aral says, “are, one, did Russia succeed in intervening in our democracy? And two, how do I measure the ROI [return on investment] from marketing investments? As I was writing this book, I realized the answer to those two questions is the same.”

Ideas for improvement

“The Hype Machine” has received praise from many commentators. Foster Provost, a professor at New York University’s Stern School of Business, says it is a “masterful integration of science, business, law, and policy.” Duncan Watts, a university professor at the University of Pennsylvania, says the book is “essential reading for anyone who wants to understand how we got here and how we can get somewhere better.”

In that vein, “The Hype Machine” has several detailed suggestions for improving social media. Aral favors automated and user-generated labeling of false news, and limiting revenue-collection that is based on false content. He also calls for firms to help scholars better research the issue of election interference.

Aral believes federal privacy measures could be useful, if we learn from the benefits and missteps of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in Europe and a new California law that lets consumers stop some data-sharing and allows people to find out what information companies have stored about them. He does not endorse breaking up Facebook, and suggests instead that the social media economy needs structural reform. He calls for data portability and interoperability, so “consumers would own their identities and could freely switch from one network to another.” Aral believes that without such fundamental changes, new platforms will simply replace the old ones, propelled by the network effects that drive the social-media economy.

“I do not advocate any one silver bullet,” says Aral, who emphasizes that changes in four areas together — money, code, norms, and laws — can alter the trajectory of the social media industry.

But if things continue without change, Aral adds, Facebook and the other social media giants risk substantial civic backlash and user burnout.