Quick Links

- UW HR Resources

Impressing: Personal Statement

Personal statement, personal statements usually fall into 3 categories:.

- The top 5% are works of writing wonder which is appreciated by all who read them but add only a little to your interview chances.

- The middle 85% are not necessarily memorable but they are well written and get a sense of you across; these may not add a whole lot to your interview chances but they don’t detract and they will hopefully create a memorable image that will be yours for the season.

- The bottom 10% are poorly written with grammatical mistakes, spelling errors, a lack of organization, or some combination of the three; these will truly hurt your chances for an interview – some committees have a zero-tolerance policy for spelling or grammar errors.

Those who write papers in the bottom 10% are often the ones who are shooting for the top 5%; we, therefore, recommend that your goal should be the middle 85%. The goal of your statement should be to explain why you want to go into emergency medicine and why you think emergency medicine is the right specialty for you.

Overarching theme

Look over your CV and think about the experiences before and during medical school that might inform what kind of emergency physician you will become. Often there is a common thread that holds together even the most disparate of experiences – this common thread is usually one of your core values as a person. This may be a good theme to weave throughout and hold together your personal statement.

Experiences to highlight

Use your experiences to give programs an idea of who you are. Be specific – talking about the aspects of care that you like in emergency medicine is good but it’s even better when programs can see how your personal experiences reinforce aspects of emergency medicine that resonate with you as a person. It’s OK to include patient vignettes and talk about your accomplishments, but be sure to relate them back to yourself. How did the experience impact you? What did you learn about yourself? How will the experience make you a better family physician? What about the experience demonstrates your commitment to the discipline of emergency medicine, your ability to work with others, and your ability to work with patients? Often choosing one experience and telling the story is a good way to open your statement, develop your theme, and make it memorable.

Commitment to specialty

Talk about why you are choosing emergency medicine. What experiences convince you that this is the right field for you?

Strengths that you bring

What do you bring to a program? What are you naturally good at? What specific skills do you have that will serve you well in residency? Give examples.

Future plans/what you are looking for in a residency program

At the end of this long road of school and training, what kind of work do you see yourself doing? This is not necessary but if you do have a sense then you should bring it up – it will help paint a better picture of you and give you something to discuss during the interviews.

Organizing your statement

There are many ways to organize your statement to get these points across. One common way of organizing the personal statement is a three to five-paragraph form reminiscent of those essays you had to write in high school. To use this approach the first paragraph tells a story to open the theme, the middle paragraph(s) fleshes out other experiences that highlight the theme and discuss your commitment to emergency medicine and what you have to bring to it, and the third paragraph reviews your strengths and future plans/training desires. However, this is a personal statement and you are free to write and organize it as you desire.

- Write in complete sentences.

- Have transitions between paragraphs

- Use the active voice.

- Make your writing interesting – use a thesaurus and vary sentence length.

- Have at least two other people (one who knows you well and one who knows the process of applying to EM residency well) read your personal statement and give feedback.

- Give yourself plenty of time to work on your statement and revise it based on feedback.

- Rehash your CV or write an autobiography.

- Discuss research or experiences that you can’t expand significantly on in an interview.

- Be overly creative ‐‐ no poems or dioramas.

- Use abbreviations – spell things out.

- Say “emergency room” or “emergency room doctor” – use the emergency department and emergency physician

- Start every sentence with “I”.

- Make it longer than one page, in single‐spaced, 12-point font.

- Have ANY spelling or grammatical errors.

- Write a statement that could be used for several different specialties (i.e. one that talks about wanting a primary care career but not specifically emergency medicine). If you are still deciding on a specialty and applying to different fields, write two different statements.

- End your essay speaking to the reader (e.g., thanking them for their time).

- Be arrogant or overly self‐deprecating.

- Focus on lifestyle issues or what you will do with all your free time as an EP.

- Focus on your being an adrenalin junkie.

- Use hackneyed stories of growth, travel, or adventure unless it really is personal and you can express that.

Adapted with permission from the copyrighted career advising resources developed by Amanda Kost, MD, and the University of Washington Department of Family Medicine

5 Emergency Medicine Personal Statement Samples

Looking at emergency medicine personal statement samples can be very useful when preparing your residency applications. Your personal statement is one of the most challenging components of the ERAS or CaRMS residency applications, but it is also one of the most important ones. Especially when you consider the fact that emergency medicine is one of the most competitive residencies . Your residency personal statement is a one-page essay that is supposed to tell the residency directors who you are, why you've chosen to pursue your chosen medical specialty - which in this case is emergency medicine - and why you are a good fit it. This blog will give you some tips for writing a strong personal statement and share five different winning emergency medicine personal statement samples that you can use as a frame of reference as you prepare for residency applications .

>> Want us to help you get accepted? Schedule a free initial consultation here <<

Article Contents 19 min read

What is the purpose of a personal statement .

If you want to write a compelling residency personal statement , you need to understand what this document is supposed to achieve. Your personal statement should highlight the "why" behind your decision to apply to a particular residency program. Essentially, you want your statement to answer the following three questions:

Imagine that you've been called for your residency interview, and the interviewer has asked \" How Will You Contribute to Our Program? \" or \u201cwhat kind of doctor will you be?\u201d. When they ask these questions, they are trying to find out what you have to offer as a candidate, and that's one of the things that your personal statement should tell them. Talk about your reasons for choosing the specialty, how your values align with theirs, your strengths and abilities, and what makes you unique as a candidate. ","label":"What will you bring to the program?","title":"What will you bring to the program?"}]" code="tab2" template="BlogArticle">

We know that it sounds like a lot of information to fit in a one-page essay. It can be challenging to get right, but it is doable. Take a look at the emergency medicine personal statement samples below and pay attention to the way that the candidates answer these questions in their essays.

On the second day of my medical school rotations, one of the attendings pointed at me and said, "Now he looks like an ER doc." I laughed because I was not surprised at all. I have always gravitated toward Emergency Medicine because it fits my personality. I am naturally energetic and drawn to a high-paced environment.

I have been convinced that Emergency Medicine is the right fit for me since my first year of medical school, and I got to put my theory to the test during my Emergency Medicine rotation. In the space of a week, we saw gunshot wounds, infections, overdoses, broken bones, common colds, and motor vehicle accidents. At first, I wasn't sure I would be able to keep up with the pace of the trauma bay, but I thrived on it.

A few weeks ago, I celebrated my upcoming medical school graduation by purchasing a 7500-piece jigsaw puzzle. It is the biggest puzzle I have ever attempted to solve, and I can't wait to get started. See, the thing is that solving puzzles of any sort makes me happy. It is one of the many reasons I hope to have a long and rewarding career as an emergency physician.

As a third-year medical student, several factors motivated me to choose a residency in emergency medicine. During my clerkship, I got to experience the fast-paced, unpredictable nature of the emergency room. I quickly found a mentor in one of the attendings that I worked with. His breadth of knowledge, enthusiasm, and calm efficiency - even when all hell seemed to be breaking loose around us - showed me how challenging emergency medicine could be. My interest was certainly piqued, and the more I learned, the more I wanted to know.

I especially enjoyed the challenges of the undifferentiated patient. Often in the emergency room, you are the first to assess and treat a patient who's come in with little more than a chief complaint. You, therefore, have to start the process of diagnosing them from the very beginning. I loved the challenge of being faced with a set of symptoms and having to identify their common etiology.

That said, the most gratifying part for me was the interactions that I had with my patients. Behind all the symptoms that I was presented with were real people from all walks of life. I specifically remember a 62-year-old man who had been brought in after losing consciousness, falling in his kitchen, and getting a deep laceration on his forehead. He was presenting with vertigo and showing symptoms of malnutrition. While I attended to his bleeding forehead, we got to talking, and he explained to me how he had recently lost his wife and had been on a juice fast so that he could try to live longer. I was able to have a conversation with him and advise him on the kind of diet that was better suited for him.

I pride myself on my ability to quickly build rapport with people, especially patients. It is a skill that has always served me well, but it had never felt so useful as it did in the emergency room. Every patient has a story, and sometimes part of treating them is taking a few minutes to ask the right questions and make them feel heard. I was honestly surprised to learn that immersing myself in the unpredictable nature of the emergency room did not mean that I had to interact less with patients. On the contrary, I feel like I got a chance to connect with more people during my emergency medicine rotation than on any other service.

It taught me that emergency physicians wear many different hats throughout the day, and depending on the situation, they can call on various aspects of their medical training. Some cases require the kind of patience and bedside manner that people typically associate with internal and family medicine, while others need a physician who is as quick, decisive, and creative as a trauma surgeon. You never know which hat you will need to wear until your patient is in front of you, and then you simply have to adapt so that you can provide them with the best care possible.

For these reasons, a career in emergency medicine would satisfy my curiosity, constant need to be challenged, and need to connect with patients. I know that I have the skills and the drive required to pursue my training and become a competent emergency physician. Leading a musical band has taught me the importance of communication and shown me that while I am capable of working on my own, I enjoy being a part of a team, and I know how to reach out for assistance when need be.

I look forward to joining a residency program that will help me develop my medical skills and that values patient care and will help me achieve my goal of becoming a caring, competent emergency physician.

When I was a child, my mother often asked me what I wanted to become when I grew up, and up until high school, the answer was never a doctor. My parents are both family physicians, as are my grandmother and my oldest sister. No one ever said anything to me, but I always assumed they wanted me to follow in their footsteps. And I felt like although I didn't want to be, I was different from them because I had no desire to pursue a career in medicine at all.

That said, when you grow up in a house full of physicians, you learn a few things without knowing it. I found that out during a camping trip with my 7th-grade class when one of my friends had an allergic reaction, and we couldn't find an adult to help. Ms. XY was in the bathroom for a maximum of five minutes, but it felt like hours for us as we watched our friend break out in hives and struggle to breathe. I decided to call my mum instead of waiting for our teacher. Whenever she tells this story, she insists that I sounded like an intern on her first day when she picked up, and I said: "X seems to be reacting to something, we are not sure what it is, but she has raised patches of skin all-over her neck and her pulse feels slower than it should be. She needs Epi, right?"

This was not a ground-breaking diagnosis, by any means but it was my first time dealing with someone who was having an allergic reaction. I remember feeling a sense of pride at the fact that I had been level-headed enough to take note of the symptoms that my friend was having and seek help and communicate effectively. After confirming that my classmate did indeed need a shot from an epi-pen, so I went to get one from Ms. X, and she administered the shot.

Even though I had a few experiences of this nature, I was still going back and forth between four different professions, and I could not decide on one. First, I wanted to be a chemist, then a teacher, then a therapist, and then a police officer, and back and forth. It was my guidance counselor in high school that helped me figure out that the right medical career could combine all the things that I love about the professions I grappled with.

I didn't believe her at first, but she was right. After a few conversations with her on the topic, I finally started looking into the different fields that medical doctors can work in. I read an article describing emergency physicians as decisive jacks of all trades, who thrive in high-energy, fast-paced environments, and it felt like they were describing me. That was when my interest in emergency medicine was piqued.

It turned into a mission during my first week of clinical rotations when I worked in the emergency room and loved every minute of it. Every single day in the x general hospital emergency department, I saw at least one gunshot wound, a person with one or multiple broken bones, a motor vehicle accident, and a person whose medical condition is nonurgent. On many days, we had to treat several of those cases simultaneously.

My time at X general hospital confirmed that emergency medicine could give me a platform to do everything I love about the other professions I had considered. As an emergency physician, I get to be on the front lines and occasionally provide preventive care. I also have to listen to my patients and make sure they feel heard and understood, all while teaching them how to take care of their bodies in order to heal correctly.

Now, I can think of no better place to spend my professional career than the emergency department, and I know that with the right training, I will be able to provide my patients with the best care possible because that is exactly what every single patient deserves.

Want an overview of the tips that we cover later in this blog? Check out this infographic:

I didn't always want to be an emergency medicine physician. Actually, when I was in elementary school, I remember telling my dad that I wanted to be an engineer because someone had said to me that they fixed broken things, and I thought that was the coolest thing in the world. I wanted to fix broken things and make people happy. It wasn't until much later that I realized that medicine allows you to do something far cooler, in my opinion: fix people's bodies.

While in college, I got the opportunity to explore the intense, fast-paced world of critical care through an internship. Within a few months of working as a scribe at the X medical center emergency department, I fell in love with emergency medicine. I worked the same hours as some doctors and saw the same number of patients they saw. As I transcribed their medical decision-making, I would imagine myself in their shoes and wonder how I would react to similar situations. The time that I spent in that emergency department gave me an in-depth look at what being an emergency room physician means daily. I got to see them be radiologists, intensivists, orthopedists, and so much more. I admired the physicians who worked in the Emergency Department and loved that they got to wear so many different hats on a given day.

Some days were busy from the moment I came in for my shift to when I would leave to go home. Other days were so quiet that I could actually study for my MCAT right in the middle of the emergency room. The calm rarely lasted long, though, and I always looked forward to the next patient because you never knew what to expect. Sometimes it was a child with a broken bone or a pregnant woman with vaginal bleeding and abdominal pain. Other times it was a drunken man who wanted to tackle everybody in his way or a police officer with a gunshot wound. I found myself excited to get to work, and I just knew that emergency medicine was the perfect specialty for me. It promised to give me a platform to make medical decisions, use the full breadth of the skills I would have as a doctor, be hands-on with my patients, and experience something different every day.

There was no doubt in my mind that emergency medicine was right for me, but I was yet to figure out whether I was a good fit for emergency medicine. When I finally got into medical school, I spent a lot of time reflecting on the qualities that I was told a good emergency physician should have. I knew that I was a good team player because I have been part of a team my whole life. As one of the founding members of a small African dance group in my city, I have always taken the opportunity to be both a leader and a team member in great stride, and we have danced together for thirteen years now. My time as president of the Pre-med Student Union at X university taught me that sometimes you have to take control, and other times, you have to ask for help and work with others. I now know how o recognize those times, and I feel comfortable in both situations.

By my third year of medical school, I was more confident in my skills, and I started to believe that I am well suited to be an emergency physician. On one particular day, I was in the residence cafeteria when a small fire broke out, and chaos erupted around me. I didn't have to think about my actions; I just knew that I needed to remain calm, look for the nearest exit, and help as many people as possible get there. One of my classmates thanked me when we got outside and told me that I was very calm under pressure, a quality that I did not realize I possessed but looking back, I could see right away that she was right. I have always thrived under pressure. I can keep a level head in busy, fast-paced environments and focus on the task I have in front of me.

This theory was tested when I saw my first patient on the first shift of my first emergency medicine rotation. I had arrived five minutes before my shift to get acclimated to the department that I would be working in that day. Right behind me were paramedics, bringing in a two-month-old male who was hypothermic, hypotensive, and barely breathing. I watched in awe as the entire medical team coordinated to intubate, place a peripheral line, administer medications, and work to save this infant's life. Everyone worked together like it was a choreographed dance, and I was able to step back, look for the place where I'd be most helpful, and jump in. I helped one of the residents run the labs, and within an hour, the little boy was stabilized and on his way to the intensive care unit.

I went home many hours and patients later, still thinking about that little boy and how the emergency team's quick and coordinated efforts potentially saved his life. Each day after that, I continued to learn. I learned during my rotations on other services and in medical school. Now, I hope to get the chance to learn from one of the best residency programs in the country so that one day, I, too, can be a part of a coordinated effort to save lives as a skilled emergency medicine physician.

Use a Residency Match Calculator will to assess your match chances this year. It's a quick and easy way to find out how competitive you are for your chosen medical specialty! ","label":"Bonus tip:","title":"Bonus tip:"}]" code="tab3" template="BlogArticle">

I am the youngest of nine children and my parent’s only daughter, so I am used to commotion, and I have learned to thrive within it. When I was growing up, our house was only quiet in the dead of night, and even then, my older brothers would sometimes be playing around in the basement. By the time I was in high school, I'd gotten so used to the chaos around me that very little could break my concentration. I am very aware of my surroundings, but I've learned to decipher what requires my attention and what doesn't. My partner often refers to it as my superpower, and I guess it is in some ways.

This superpower served me well when I first moved to the United States at the age of sixteen and had to spend most of my free time studying. I was able to study in the busy cafeteria during lunch period and in loud classrooms during free periods. I even managed to do my homework in the stands at football games while my brother was playing on a few occasions. I grew up in France, so moving to America meant learning a new curriculum in a language that I did not speak very well at the time. The first few weeks were challenging, but once I figured out how to use my superpower to put in more study hours, I started making progress. Eventually, I graduated in the top 25% of my class.

I approach everything that I do with this same dedication and work ethic. I did it throughout my undergrad years, when I worked as a teacher's assistant, ran track for the school team, and completed my degree in biotechnology. I also did it in medical school, where I discovered that I genuinely enjoy teaching by offering tutoring lessons. I plan to continue in this way during my residency and during what I will work to ensure is a long and fulfilling career.

I believe that my perseverance and passion will help me along the way as I train to become a doctor, but it is because of my curiosity, compassion, and love for the field that I know that with the proper training, I can be a great emergency physician. When I was in primary school, we had a career day, and one of my classmates' friends came in and told us all about his work as an ER doctor. He talked about how he got to heal kids and adults who were hurting, and then he gave us lollipops and told us that if we worked hard, we could do it too. I was sold! At the dinner table that evening, I explained to my family that I was going to become a doctor. They all assumed it was because of the lollipop, but my interest had just been piqued, and the more I've learned about medicine since then, the more I've wanted to know.

I had always been drawn to emergency medicine because of the fast-paced and unpredictable nature of the emergency room. During my clerkship, I got to learn more about the core specialties in medicine, and I confirmed that emergency medicine was perfect for me. One of the attendings that I worked with in the ER told me that "emergency doctors are people who just like doing things, all the time." She told me that she knew it was right for her when she realized that she was just as comfortable around big scary things like traumas and codes as when dealing with children with appendicitis.

Her words stayed with me because they described precisely how I felt during my time in the emergency room. I loved the diversity in patients' presentations—surgical, medical, social, psychiatric, etc. I loved being required to think on my feet and act quickly to provide lifesaving or limb-saving care at a moment's notice.

Emergency medicine is the perfect platform for me to utilize my superpower, work ethic, and passion for medicine to provide patient care in an environment that is almost reminiscent of the home I grew up in. I cannot imagine a more fulfilling career path for myself.

Five Tips for a strong personal statement

1. start early.

Writing a residency personal statement, especially for a competitive field like emergency medicine, is not something that you can rush through. We recommend that you give yourself at least six to eight weeks to brainstorm, write, edit and polish your personal statement. The earlier you start, the more time you will have to review your statement and get a second pair of eyes to look at it to ensure it is as compelling as possible. You do not want to be scrambling at the last minute and end up with a subpar essay because you waited until the last minute to get the job done.

The key to an excellent personal statement is preparation. You should take the time to brainstorm and plan the structure of your essay for two reasons: First, because having a structure will guide you and keep you on track as you write. Secondly, because we tend to get attached to our work, and if we get to a point where we realize that the flow of the personal statement is off, it is harder to delete a whole paragraph than it is to just rewrite a few sentences. We suggest that you brainstorm first. Think about the questions that we mentioned earlier and write down your answers to those questions, as well as any memorable experiences that have contributed to your decision to become a physician.

4. Stay true to yourself

Students often make the mistake of writing what they think the program directors want to hear instead of the truth. This usually backfires because it can end up sounding cliché and generic, but also because it will likely not be consistent with the rest of your application. Your personal statement should be about you and your suitability for the residency program. So, be honest and don't try to fabricate your statement or exaggerate your experiences. Instead, tell the residency program directors about your exposure to medicine, what you've learned, and how your experiences led to you wanting to pursue this vocation.

Have you started preparing for your residency interviews? This video is for you:

5. Seek feedback

It's not enough to make statements about yourself. If you want to write a compelling statement, you need to back your claims up with specific examples or short anecdotes. Not only do people tend to remember such things more, but it is just a more impactful way to write. For example, instead of saying, "I am good at handling stress," you could say, "My role as the oldest sister of five children has often tested my ability to handle stressful situations." The second sentence is more memorable, and if you followed it up with an anecdote about one of those stressful situations, it would be even more impactful. It shows the directors that you have experience dealing with stressful situations, and it also gives them some new information about your background.

Your residency personal statement shouldn't be longer than one page unless otherwise specified. You should aim for an essay that is between 650 and 800 words.

Your personal statement should tell the program directors why you've chosen to pursue your specialty, why you're suited for it, and their program.

They are an essential part of your residency application as they give you a chance to tell the program directors why you are a good fit for your chosen field and their program in your own words. You should definitely not underestimate their importance.

While you can certainly send different versions of your personal statement to different programs, we do not recommend that you address them to any program in particular because this would mean writing several different personal statements. Instead, focus on writing personal statements that are tailored to specific specialties.

That depends on the concern in question. You should only discuss issues that you haven't addressed in other application components and that are relevant to the rest of your statement. If you address any red flags, make sure you demonstrate maturity and honesty by taking ownership of the problem and explaining how you've learned and grown from your mistakes.

Yes. Emergency medicine is one of the most competitive residencies, so you need to ensure your residency application is compelling if you want to secure a spot in a top program.

No, you do not. Most students apply to 15 - 30 residency programs in one application cycle, so writing a letter for each one is simply not feasible. Instead, you should write a letter for each specialty that you are considering.

You can write a strong personal statement if you take the time to brainstorm and plan for your essay early, use specific examples in your writing, and seek feedback from experts.

Want more free tips? Subscribe to our channels for more free and useful content!

Apple Podcasts

Like our blog? Write for us ! >>

Have a question ask our admissions experts below and we'll answer your questions, get started now.

Talk to one of our admissions experts

Our site uses cookies. By using our website, you agree with our cookie policy .

FREE Training Webinar:

How to make your residency application stand out, (and avoid the top 5 reasons most applicants don't match their top choice program).

Tips for Writing Your Personal Statement

Writing an amazing residency personal statement on your ERAS application is about telling your story in your own voice. It’s about telling the reader something about you that cannot be gathered from other parts of the application.

The personal statement is a longer discussion of yourself, motivation, and experiences. It is also an important element of your application as 67% of residency programs cite personal statements as a factor in selecting students to interview. We’ve put together some tips to help you below.

“Do’s” of writing personal statements :

🗸 DO tell a story about yourself or share a unique situation. You are showing the reader your narrative about why you are a great candidate for residency.

🗸 DO make it human. Approach the statement as an opportunity to process life experiences and articulate the arc of your journey.

🗸 DO be specific. Clearly outline your interest in the specialty, and use concrete examples where able.

🗸 DO be candid and honest.

🗸 DO pay attention to grammar and writing style.

🗸 DO keep the statement to one page.

🗸 DO get an early start. We recommend to begin writing your personal statement during the summer between your third and fourth years of medical school to allow ample time for revisions and reviews. Be prepared to do many drafts.

🗸 DO include personal challenges you have overcome in your medical education journey so far.

🗸 DO get feedback. Have multiple people read your statement including faculty in your field.

What to avoid :

✖ DON’T tell the reader what an emergency physician does; he or she already knows this.

✖ DON’T belittle another person or specialty.

✖ DON’T overestimate your personal statement. The benefit gained from even an outstanding personal statement is still marginal compared with other aspects of your application which carry more weight.

✖ DON’T underestimate your personal statement. A poorly written or error-filled personal statement can drag down your candidacy.

✖ DON’T just focus on activities that the admissions committee can learn about from your application. Use this opportunity to give NEW information that is not available anywhere else.

Questions to Consider When Writing

Crafting a strong personal statement begins with self-reflection. Before you even begin writing, lay the groundwork for your statement by asking yourself the following questions:

Why are you choosing emergency medicine? If you want to help people, why don’t you want to be a social worker or a teacher (for example)? What interests, concerns, or values drive you in your studies, work, and career choice?

Think back to volunteer, shadowing, global health, research, work, and coursework experiences. What has been defining? Are there any moments that stick out? What did you learn about yourself or your future profession? How did you change after that experience?

What do you want the residency program to know about you as a person, a student, and a future colleague? What makes you a good fit for the profession and the profession a good fit for you?

What makes you unique from other applicants?

Additional Resources

Most universities and colleges also have writing centers that may be able to help you focus your ideas into a theme or read and give feedback on your personal statement.

*This resource is intended to serve as inspiration and a compass to guide your own writing. All personal statements or parts thereof may not be reproduced in any form without written permission of the author.

- AI Content Shield

- AI KW Research

- AI Assistant

- SEO Optimizer

- AI KW Clustering

- Customer reviews

- The NLO Revolution

- Press Center

- Help Center

- Content Resources

- Facebook Group

Emergency Medicine Personal Statements: a Free Guide

Table of Contents

With the examples and tips shared in this article, crafting an effective personal statement for emergency health workers should no longer be a problem.

Admittedly, this can be daunting, especially with limited guidance and resources available. But fear not. This free guide provides you with everything needed to compose a unique and compelling essay that will stand out from the rest.

To make things easier, you’ll also find an emergency medicine personal statement sample to help you get started.

Tips for Writing Emergency Medicine Personal Statements

Convey a clear purpose.

When writing an emergency medicine personal statement , it is important to capture the essence of why you want to pursue the career.

In addition, show how your current experiences have shaped your passion for the profession. Ensure that your introduction conveys a clear purpose and concisely explains your motivation and inspiration.

Structure It Logically

A major key when crafting a compelling essay is effectively structuring the content. Begin with a succinct paragraph outlining your objectives before delving into details about your academic background.

Go on to discuss any relevant skills or experience, as well as other attributes which would make you an ideal candidate for emergency medicine. Be creative in showcasing your strengths but be mindful not to stray from the primary topic of the essay.

Maintaining focus throughout the personal statement is essential. Ensure that each sentence adds value toward reinforcing your overall message and goal. Vague descriptions and rambling should be avoided.

Try to get to the point quickly and stick to facts rather than opinions. Additionally, consider using active voice sentences, as they usually create more engaging content.

Stay Honest

Remember to stay grounded. Although it is good practice to showcase yourself in a positive light, do not go overboard by listing unsubstantiated claims or unrealistic accomplishments. Stay honest, humble and realistic throughout the entire statement. Provide evidence for every assertion you make within the essay instead of relying on mere words alone.

Adhere to Proper Grammar Rules

Adherence to proper grammar rules is vital for creating an effective piece of writing. No matter how interesting or complex your ideas may be, it won’t count for much if your essay is riddled with errors.

Emergency Medicine Personal Statement Sample

This section contains good examples that can inspire you as you write yours. Read through and select the emergency medicine personal statement sample that best reflects your aspirations.

I am a passionate medical professional with an unwavering commitment to providing the highest quality of emergency care. Throughout my career, I have continually sought out opportunities to develop and hone my expertise in this field. I shadowed experienced physicians during medical school, and I completed several residencies in emergency medicine. My ultimate goal is to combine my dedication to patient-centered care with my enthusiasm to provide the best outcomes possible for patients.

A major source of motivation throughout my studies has been the opportunity to gain insight into different facets of emergency medicine. To supplement these experiences, I have also pursued additional coursework on topics such as environmental health and injury prevention. My studies have not only sharpened my clinical judgment but have allowed me to appreciate the complexities of healthcare provision in today’s world.

I strive to be an advocate for those in need of emergency medical attention, regardless of their background or identity. In everything that I do, I aim to provide personalized and compassionate care while always putting safety first. Moreover, I prioritize a continual exchange of information between myself and the patient so that we can collaborate together toward achieving better health outcomes. This holistic approach is something I take great pride in, especially when it comes to ensuring that each patient leaves the ER feeling safe.

As someone eager to challenge themselves in this exciting field, I’m confident that I will bring energy and enthusiasm to any emergency medicine role. By continuing to pursue opportunities to expand my knowledge base and training, I believe I could make a positive contribution to any organization.

I have had a lifelong passion for emergency medicine, and I am determined to pursue a career in it. With over seven years of experience working as an Emergency Medical Technician, I bring an extensive set of skills and abilities to the field. My experience has enabled me to develop a holistic approach to patient care. At the same time, I try to be aware of every detail needed to provide fast and effective treatment. From traumas to cardiac emergencies, I always display poise, confidence and decisiveness, even when faced with chaos and pressure.

Furthermore, my involvement in several research projects, including one related to improving stroke care outcomes, has helped me understand the importance of evidence-based practice. Additionally, through medical residencies and volunteering at free clinics, I was able to hone my communication and collaboration skills. These skills enable me to work well within teams, discuss complex topics with patients and form meaningful relationships. This knowledge and my unwavering commitment to contribute to the betterment of healthcare have enhanced my enthusiasm for pursuing residency training in emergency medicine.

I firmly believe that these qualities make me highly qualified for a residency position. With ambition and determination, I’m sure that I can help foster team spirit and promote safe clinical environments that provide quality patient care.

Personal statements are like formal advertisements . They allow you to sell yourself and your ability to people in authority . This article focuses on writing personal statements for emergency medicine. The tips and examples therein can help you create a convincing personal statement.

Abir Ghenaiet

Abir is a data analyst and researcher. Among her interests are artificial intelligence, machine learning, and natural language processing. As a humanitarian and educator, she actively supports women in tech and promotes diversity.

Explore All Write Personal Statement Articles

How to draft meaningful length of law school personal statement.

Are you confused on how to write a law school personal statement? One of the essential elements of your application…

- Write Personal Statement

Effective History and International Relations Personal Statement to Try

Are you considering studying history and international relations? Or you may be curious about what a degree in this field…

Guide to Quality Global Management Personal Statement

Are you applying for a global management program and want to stand out from the crowd? A well-written personal statement…

How to Draft Better Examples of Personal Statements for Residency

Achieving a residency can be a massive accomplishment for any aspiring medical professional. To secure your spot in one of…

Tips for Drafting a Free Example of Personal History Statement

A personal history statement can be crucial to many applications, from university admissions to job search processes. This blog will…

Writing Compelling Dietetic Internship Personal Statement

Applying for a dietetic internship is a rigorous process and requires submitting a personal statement, which is an essential part…

- EM Resident

- Publications

- Join/Renew EMRA

Popular Recommendations

- Board of Directors

- EMRA Committees

PEM Personal Statement Example

Provided by michele mcdaniel.

From the moment I took my first, tremulous step through the doors of the hospital with my freshly ironed white coat and my newly minted title of MD, I knew I wanted to have a career in the field of pediatric emergency medicine. To anyone who loves kids, the reasons are obvious, plentiful, and easy to understand. Children are fun! They are vibrant and happy, and, for the most part, when they present to your ED, some combination of a silly face, a sticker, a popsicle, and your flavored antipyretic of choice cures what ails them and they go home to continue being cute little monsters. However, to people like you and me, who are passionate about the field of pediatric emergency medicine, the reasons for choosing this career resonate much deeper.

I can remember one specific case which will stick in my mind forever. As an intern, I picked up a chart with the chief complaint "fever". When I opened the door to walk into the room I found a mother, sobbing, clutching her toddler son to her chest. It didn't take me long to realize that the fever wasn't the only reason she had come. On speaking with her, I discovered that her son had suffered a febrile seizure. She was terrified, and visibly much more upset than her peacefully sleeping child. After listening to her story, we proceeded to discuss what had happened. She had no idea that a simple febrile illness could cause a seizure, and was relieved to know that her child most likely would never have another event. Over the course of our conversation, I could see her relax, and she left at peace and thanked me for doing something which required no medical skill at all, simply being available to talk - one human to another.

This case illustrates well those things that attract me to pediatric emergency medicine. I challenge anyone to find another specialty in which you see a comparable breadth of disease. Take for example the case of a febrile seizure. Do you know any adult who has seized during the course of his or her febrile URI? It never ceases to amaze me just how much medicine you need to know in order to complete even one shift in the peds ED. There are an endless number of diseases that present more commonly in a certain age group, have a symptom complex congruent with a variety of disease processes dependent upon the patient's age, or have a completely different presentation based on whether your patient is 6 months or 6 years old.

But it's not only the diagnostic challenge that excites me. I also enjoy the non-medical aspects of working with children as patients. The pediatric emergency department is a venue where communication skills go a long way. Whether you're demonstrating the superpowers of your "magic flashlight" in order to look in a three year old's ears, easing a mom's worries about a high fever, or making a consult, effective communication is extremely important. It is also helpful in identifying ways to make a difference for your patients beyond the prescription pad. The pediatric ED is perfect place to discuss prevention - bike helmets, proper car seat placement and seat belts, avoiding tobacco/alcohol/drug use, safe sex practices - the list is endless. The pediatric emergency department is also a fertile ground where advocacy takes root and flourishes. There are so many opportunities to reach out to young, malleable minds that you only have to dream up an initiative and you can make a difference that can span generations.

I have been fortunate to be a part of several different advocacy projects during my time at Indiana University. Whether it was fitting bike helmets and guiding young bike riders through an obstacle course, teaching mentally and physically handicapped children how to tell their life stories through photography, or coaching elementary students who'd never swum an entire length of the pool through a triathlon, I've enjoyed every opportunity to reach out into my community. This is something I intend to carry on through my time in fellowship. I have a particular interest in the area of non-accidental trauma, and I hope that, between the skills I've learned in my past advocacy work, my upcoming elective with the child protection team, and the knowledge I'll gain during my fellowship training, I'll be able to translate community-based research into community-based initiatives that will aid in prevention of child abuse in the future.

Beyond being a venue for furthering my interest in advocacy and research, I also know that a fellowship in pediatric emergency medicine will allow me to develop the skill set I need to achieve my career goals. I hope to one day work in both the adult and pediatric emergency departments at a large academic center and pass on the fruits of my education and experience to the next generation of emergency physicians. Having past experience in coaching and teaching, and having recently begun to have "staffing shifts", I know my passion lies in sharing my knowledge with others, and I look forward to each opportunity I'll have to gain more experience in the field of teaching and mentoring. I hope to one day be a successful clinician educator and I know that, by combining the knowledge and skill I'll gain from fellowship and my existing passion for emergency medicine (especially pediatric emergency medicine), I'll have a fulfilling and exciting career for many years to come.

I love what I do, and I'm looking forward to the next few years in which I'll be able to build a strong foundation for my future career. I know that I'll be able to provide as much enthusiasm and dedication to my program as I will gain knowledge and skill that I'll carry forward. I can't wait to be a part of the pediatric emergency medicine family, and I'll be proud to call myself your colleague one day.

Related Content

Aug 25, 2017

The Emergency Medicine Residents' Association EMRA is the voice of emergency medicine physicians-in-training and the future of our specialty and the largest and oldest independent resident organization in the world. EMRA was founded in 1974 and today has a membership over 18,000 residents, medical students, and alumni.

Jan 19, 2018

Emergency Medicine Wellness Week

When Lightning Strikes

- EM RESIDENT

- ADVERTISE & EXHIBIT

- Connect with us

EM can lead the way in addressing healthcare inequities. But first we must face the deficiencies of diversity, equity, and inclusion in our field. It starts with training.

Make sense of the chaos of the trauma bay with the emra trauma guide., mobilem put every emra guide in your pocket..

© 2021 Emergency Medicine Residents' Association | Privacy Policy | Website Links Policy | Social Media Policy

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Thematic Analysis of Emergency Medicine Applicants’ Personal Statements

Xiao chi zhang , md, ms, jeremy lipman , md, randy jensen , md, phd, kendra parekh , md.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author.

Collection date 2019 Sep.

The personal statement is an important part of the residency application. Although guidance exists, the composition of personal statements is not standardized; each statement reflects an applicant’s unique personality. In emergency medicine (EM), the personal statement could thus provide insight into why applicants are choosing EM and what they hope to accomplish in the field that could guide advisors and applicants.

To perform a thematic analysis of personal statements from applicants accepted into an academic EM residency program to gain insight into what successful applicants include in their personal statements, why applicants are pursuing careers in emergency medicine, and anticipated career goals.

Thematic analysis was performed on ten randomly selected personal statements from matched allopathic, U.S. applicants at a single, large, urban 3-year EM residency program between 2008 and 2015. Themes and sub-themes were identified and analyzed for frequency.

Ten personal statements were analyzed. Thirty-one (31) unique themes were identified and grouped into five main themes: personal characteristics related to a career in EM (38.3%, 116/303), why I love EM (36%, 109/303), my story (13.5%, 41/303), my career in EM (8.9%, 27/303), and ideal characteristics of a residency program (3.3%, 10/303). The most common personal characteristics described were altruism and the ability to work well under pressure. Applicants love EM due to the diversity of patients and disease presentations and the ability to perform procedures.

Conclusions

Thematic analysis of EM applicants’ personal statements highlights the uniqueness of EM as a specialty and what draws applicants to EM.

Keywords: Emergency medicine, Medical student, Personal statement, Residency application, Texual analysis

Emergency medicine (EM) is becoming a highly competitive specialty with 1.2 to 1.3 applicants for each available spot [ 1 ]. In 2017, there were 3575 medical students who entered the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP), hoping to pursue a career in EM, and each EM residency program received an average of 941.8 applications [ 1 ]. As the number of applications per program increases, it becomes more challenging for the selection committee, usually comprised of program directors and associate program directors, to screen and select applicants for interviews. While a universal medical application includes academic achievements, transcripts, United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) scores, and standardized letters of evaluation (SLOEs), one of the most uniquely personal aspects of the Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) application is the personal statement.

A compelling personal statement plays a significant role in the overall application process by providing the opportunity for applicants to embed their personality, interests, and passion for EM into their application beyond the constraints of a curriculum vitae [ 2 , 3 ]. Personal statements also provide program directors insights into applicants’ understanding and expectations of a career in EM. In the NRMP’s 2016 Program Directors survey, 66% of program directors cited personal statements as a crucial determinant in selecting applicants for interviews with an importance rating of 3.3 out of 5 [ 4 ]. Program directors also cited professionalism and personality with respective importance ratings of 4.9 and 4.5 out of 5, factors which are often reflected in the personal statement [ 4 ]. Some have even viewed the personal statement as an applicant’s perceived professional identity [ 5 ].

While formal and informal guidelines for writing personal statements are available from the American Medical Association (AMA), the Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors (CORD), medical school writing workshops, and student-centered websites, the impact of these efforts is unknown [ 6 ].

To our knowledge, the content of EM applicants’ personal statements has neither been explored nor previously published. Thus, the purpose of this study is to perform a thematic analysis of personal statements from applicants accepted into an EM residency program to better determine what successful applicants include in their personal statements and their perceptions of the specialty.

Personal statements of matched allopathic, U.S. applicants at a single, large, urban 3-year EM residency program between 2008 and 2015 were considered for inclusion in the study to ensure that no current residents at the time of the study would be included in the sample. Osteopathic and international medical graduates were excluded from this analysis as they make up a small portion of the EM applicant pool. During the study selection period, the EM residency admission committee was comprised of one program director and two associate program directors, all with various levels of education and leadership experience.

All eligible personal statements were screened for completeness and fully de-identified prior to analysis. Purposive sampling was used to create a sample representing the majority of applicants to EM residencies. Thematic analysis was used to explore the contents of EM applicants’ personal statements using an inductive coding approach to ground the study [ 7 ]. Manifest and latent coding were used to optimize the reliability of the thematic analysis. From the 100 available personal statements, two were randomly selected for generation of themes. All four authors, each with extensive experiences in residency selection (two authors were non-EM program directors, one author was the Director of Undergraduate Medical Education and EM Clerkship Director, and one author was Core Faculty and Assistant Director of an EM Clerkship), independently generated themes from these two personal statements. The authors then met to review and edit the themes through a collaborative, iterative process until the final themes were generated in consensus. Common themes identified by the authors were similar to those identified in prior studies in surgical specialties [ 8 ]. After thematic generation, ten (10) statements were randomly selected for analysis with plans to supplement these statements with additional personal statements as necessary to achieve theme saturation.

To identify themes, the authors divided themselves into teams of two; each team was responsible for independently identifying themes in half (5) of the personal statements. To minimize researcher bias, each team included a non-EM trained physician and an EM-trained physician. The authors utilized Dedoose [ 9 ], a qualitative data management software program, to code the statements and analyze the data for frequency of themes and sub-themes. Once each team concluded its independent review, both teams would review the personal statements coded by the other team before reaching consensus on the identification of the themes for all ten personal statements. This study was deemed exempt by the Thomas Jefferson University Institutional Review Board.

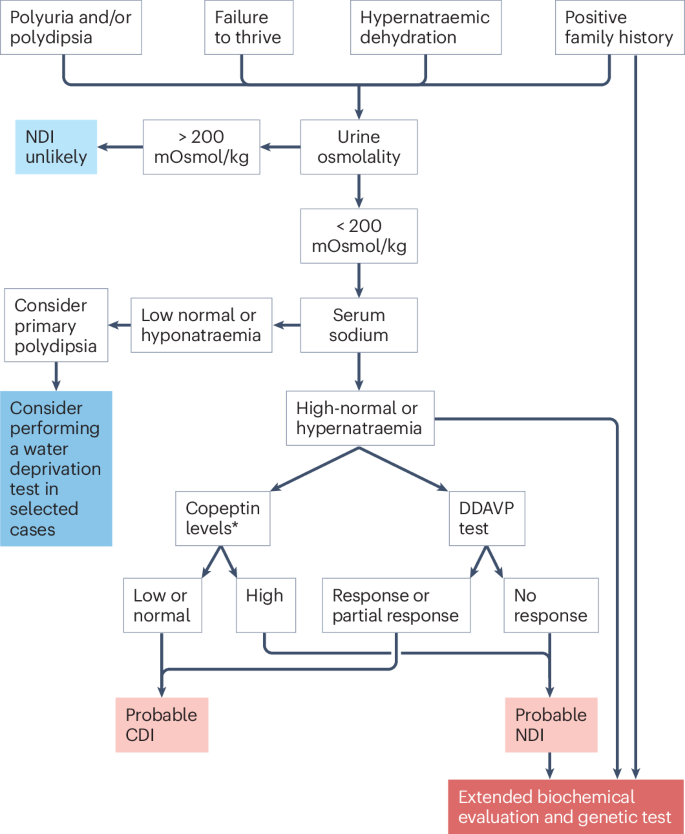

Ten (10) personal statements were analyzed. Thirty-one (31) unique themes were identified and grouped into the following five main themes (Table 1 ):

Personal characteristics related to a career in EM (38.3% of themes): This theme includes personal characteristics that make the applicant suitable for a career in EM such as being altruistic or working well under pressure.

Why I love EM (36% of themes): This theme includes the reasons why an applicant specifically chose emergency medicine for a career, such as the diversity of patients and the ability to perform procedures.

My story (13.5% of themes): This theme includes a personal story of growth and overcoming challenges and personal experiences with the medical system that inspired the applicant to pursue medicine as a career.

My career in EM (8.9% of themes): This theme includes what applicants aspire to in their future careers as emergency medicine physicians and includes goals such as pursuing specific research interests or fellowships.

Ideal characteristics of a residency program (3.3% of themes): This theme focuses on the characteristics of the applicant’s ideal residency program such as a challenging environment that offers autonomy or caring for an underserved population.

Frequency of themes and sub-themes determined by a random selection of personal statements for emergency medicine (EM) residency from a tertiary academic center from 2008 to 2015

| Codes grouped by theme | Frequency ( ) | Percent of total codes |

|---|---|---|

| My story | 41 | 13.5 |

| Clinical vignette | 9 | 3.0 |

| Volunteer experience in medical setting | 11 | 3.6 |

| Personal experience with medical system | 5 | 1.7 |

| Story of personal growth | 16 | 5.3 |

| My career in EM | 27 | 8.9 |

| Leadership | 8 | 2.6 |

| Academic and research | 11 | 3.6 |

| Clinical medicine | 8 | 2.6 |

| Personal characteristics | 116 | 38.3 |

| Identifying problems | 11 | 3.6 |

| Part of a team | 8 | 2.6 |

| Thrive in chaos | 5 | 1.7 |

| Work ethic | 6 | 2.0 |

| Work unusual schedule | 3 | 1.0 |

| Work well under pressure | 15 | 5.0 |

| Altruistic | 24 | 7.9 |

| Decision making | 7 | 2.3 |

| Demonstrate EM knowledge | 5 | 1.7 |

| Determination | 11 | 3.6 |

| Manage complex situations | 5 | 1.7 |

| Personal accomplishments | 16 | 5.3 |

| Residency program characteristics | 10 | 3.3 |

| Better doctor | 6 | 2.0 |

| Independence | 1 | 0.3 |

| Challenging | 3 | 1.0 |

| Why I love EM | 109 | 36.0 |

| Alleviate suffering | 6 | 2.0 |

| Differential diagnosis | 14 | 4.6 |

| Diversity of patients | 31 | 10.2 |

| First point of contact | 6 | 2.0 |

| Impact long term health | 10 | 3.3 |

| Motivating patients | 3 | 1.0 |

| Procedures | 15 | 5.0 |

| Acuity of patients | 14 | 4.6 |

| Preventive care | 10 | 3.3 |

A total of 303 theme statements were applied across the 10 personal statements, with an average of 30.3 themes per personal statement (SD = 8.01, range = 21–46). Table 1 displays the frequency of themes. Table 2 displays selected quotes from the common themes and sub-themes.

Selected quotes or emergency medicine personal statements as characterized by the five main themes

| Themes | Selected quotes |

|---|---|

| Personal characteristics related to a career in EM | Altruism: “Contributing to the community has been a standard that I have upheld throughout my adulthood.” “I am driven to provide for the needs of my patients and provide them with the best possible service.” Personal accomplishments: “I founded the international health interest group, Global Health Forum, which introduces medical students to current issues in international health and helps them gain medical experience abroad during their education.” Work well under pressure: “My even-tempered, quick, logical thinking during stressful situations will complement nicely my other attributes.” “I am well suited for emergency medicine because of my ability to work under pressure, and to stay calm and think logically in stressful situations.” |

| Why I love EM | Broad patient and disease presentations: “I can deal with the drunk who is uncooperative, the rambling schizophrenic or the demented elderly person.” “What fascinated me the most was the variety of the field, as no two shifts in the emergency room are ever the same. The profession has elements of nearly every field of medicine - from procedures, to primary care, to obstetrics/gynecology, to psychology, and everything in between.” Patient acuity: “Although Emergency Medicine can be considered the ‘jack of all trades’ specialty in certain regards, it is commonly misunderstood that they are, in fact, masters of acute intervention and prioritization.” “…stabilizing the unstable patient…” Forming differential diagnoses: “What I enjoy about emergency medicine is the constant need to think about atypical presentations for common diagnoses.” “I enjoy the responsibility of formulating a differential based on the history and interrogating those suspects with a complete, but directed physical exam and laboratory studies.” |

| My story | Personal growth: “…these changes have been immeasurable treasures that allowed me to grow into the person I have become.” “During this time, I learned the valuable lesson of how to deal with adversity while fulfilling my professional commitments.” Volunteer/personal experiences: “I learned that my mother had been living with the secret of advancing breast cancer which she had kept from her family, her friends, and even her doctor.” “In my undergraduate years I volunteered for 4 years at a community emergency department, as well as with Habitat for Humanity.” Clinical vignette: “I remember one patient with an asthma exacerbation due to crack cocaine use. The medical team gave him some nebulizer treatments. It soon became obvious he was not responding to the treatment and the attending physician performed a rapid sequence intubation. The experience inspired me.” |

| My career in EM | Future goals in emergency medicine: “Beyond residency, I hope to complete a fellowship in International Emergency Medicine.” “I plan on continuing to make research a part of my career and hope to bring more evidence-based practice to the field of Emergency Medicine.” |

| Ideal characteristics of a residency program | “I seek a residency program that is as excited at producing excellent physicians as caring for anyone, with anything, at any time.” |

All personal statements included a discussion of such personal characteristics. Some applicants provided specific examples of characteristics, while other applicants simply stated that they possessed the characteristic. The most commonly cited personal characteristic was being altruistic, followed by personal accomplishments and specific examples of how they work well under pressure.

The next most commonly identified theme was why I love EM, and all ten personal statements included comments reflecting this theme. Applicants discussed a myriad of reasons why they love the field of emergency medicine. The most commonly cited reason was the diversity of patients and disease presentations, being able to perform procedures, the acuity of patients, and building a differential diagnosis. Patient acuity was described in specific terms by listing acute conditions such as acute stroke and acute coronary syndrome as well as in general terms about managing acute needs..

This theme was identified in nine out of ten personal statements. There was diversity in how applicants discussed their story, from accounts of personal growth to experiences within the medical system, and specific clinical vignettes that inspired them to choose EM. Finally, all personal statements included comments about the applicant’s expected future career, which included post-residency goals as well as ideal residency program characteristics..

Occurrence of themes was also identified among the personal statements. The most commonly co-occurring themes were personal accomplishment and leadership, preventive care, and impacting long-term health. The next most common co-occurring themes were identifying problems and working under pressure, altruism and determination, and differential diagnosis and diversity of patients.

This study marks the first published report on personal statement contents from successful applicants to emergency medicine residency programs. The most commonly expressed themes in applicants’ personal statements were the description of personal characteristics that made the applicant well suited for the specialty. Applicants often provided specific characteristic examples that made them particularly prepared for a career in EM (Table 1 ). Previous work focusing on applicants’ personal statements to other residencies (internal medicine, general surgery, ophthalmology, and pediatrics) also identified similar themes to those characterized in our study [ 5 , 8 , 10 , 11 ]. Our analysis identified that EM applicants frequently discussed their ability to work well under pressure and altruism, which appears to be a theme unique to EM personal statements when compared with the work done in other specialties. Describing personal characteristics is in keeping with the American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC)’s advice to portray marketable abilities [ 12 ]. Additionally, the characteristics mentioned by applicants—altruism and ability to work well under pressure—represent distinct personality characteristics of EM residents when compared to the general physician population [ 13 ].

It is noteworthy that discussion of why I love EM is included in all the personal statements examined in this study. The most commonly cited reason was the diversity of patients and disease presentations. This element has been identified in personal statements from internal medicine applicants, and we posit the frequency of this theme within EM applicants may be attributable to publications that recommend including this element [ 5 , 10 , 14 ]. Interestingly, this theme was not found in personal statements of those pursuing anesthesia or radiology residencies [ 3 , 15 ]. This discrepancy may relate to different resources and advising strategies for students applying to these fields or specialty-specific differences in expectations. The next most commonly mentioned reason for pursuing a career in EM was the opportunity to perform procedures; this reason was also identified as a common theme in applicants to surgical residences but not by applicants to internal medicine and pediatrics [ 8 , 10 , 11 ].

EM applicants also expressed an attraction to the acuity of care and taking care of patients in the acute phase of illness. This provides a unique perspective compared to themes identified in the literature concerning other specialties [ 3 , 5 , 8 , 10 , 15 – 17 ]. This finding along with the identification of specialty-specific personal characteristics again highlights the specialty-specific information that can be gleaned from personal statements. This may inform program directors of the alignment between applicant and program goals for training.

Almost all applicants discussed my story, which was their personal narrative for why they chose EM. This theme was presented in a wide variety of ways, but universally, the applicants explained their journey from an influential tipping point (e.g., personal experience or volunteer experience) to the present state of applying for an EM residency. This theme was also identified in dermatology, general surgery, internal medicine, ophthalmology, and pediatrics residency applicants [ 5 , 8 , 10 , 11 , 18 ]. This is also in keeping with the AAMC’s Careers in Medicine advice that the personal statement “be personal” [ 12 ]. The presence of this theme across multiple specialties may indicate good penetrance of the AAMC’s Careers in Medicine advice or natural concordance and agreement among program directors about what is important in a personal statement.

Due to a high prevalence of common features within personal statements across specialties, there is an overall perception that these documents are becoming more impersonal over time [ 3 ]. We have identified common themes found in personal statements written by applicants who ultimately matriculated to academic EM residency programs. Thus, an argument can be made in favor of standardizing the personal statement. This could potentially be advantageous to both programs and applicants if executed appropriately. If there was consensus among program directors for a given specialty on which theme(s) they find most useful in selecting applicants for interview, applicants could be encouraged to focus their statements on those theme(s). Program directors would have additional information perceived as valuable and applicants could more clearly focus on their narratives.

However, the goal of the residency application process is to identify which applicants best fit at a training program, and although the residency application incorporates information from a variety of sources, the personal statement remains the only portion of the application that provides a direct dialogue from the applicant to the program. As such, it allows for creativity and provides a tremendous opportunity for the applicant to identify and accentuate the elements of their application and background they believe would be most helpful to a selection committee. Our study identified unique characteristics discussed in personal statements that reflect the unique characteristics of emergency physicians demonstrating that it is possible to have distinction among personal statements. This could be lost with standardization of personal statements.

Limitations

This study was conducted at a single institution, with randomly selected statements, over an 8-year time frame, and only included applicants who matched into EM. Common themes may be different for applicants who go unmatched. Similarly, the statements were from applicants who matched at an academic residency program. Themes from applicants applying to a primary community program may be different. Osteopathic and international applicants were excluded, and these personal statements may express different themes than those captured in this study. Additionally, we acknowledge our sample size was small, and we did not consider other factors that might influence personal statements, nor did we attempt to analyze whether these personal statements improved or hindered the applicant’s likelihood of matching.

This study marked the first attempt at thematic analysis of personal statements of accepted applicants at an allopathic 3-year EM residency program. All statements included discussion of personal characteristics that make the applicant suitable for EM, why the applicant loved EM, and the applicants’ future goals. The most commonly cited personal characteristics were altruism and an ability to work under pressure. The most commonly discussed reasons for loving EM included the diversity of patients and being able to perform procedures. While this study was limited to a small sample of personal statements at a single institution, the themes identified in personal statements can be helpful in informing program directors how applicants view the practice of emergency medicine and can help guide prospective applicants on how to structure their personal statements. Future studies will be conducted to expand this pilot study by analyzing personal statements from multiple EM residencies and including osteopathic, international, and unmatched applicants. Further exploration could also include the impact of gender and underrepresented minority status on personal statements.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

This study received an ethical approval (IRB-Exempt no. 18E.436).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Xiao Chi Zhang, Email: [email protected].

Jeremy Lipman, Email: [email protected].

Randy Jensen, Email: [email protected].

Kendra Parekh, Email: [email protected].

- 1. AAMC. Electronic Residency Application Service Statistics 2017. https://www.aamc.org/services/eras/stats/359278/stats.html .

- 2. Association of American Medical Colleges. (2018). Historical Specialty Specific Data: Emergency Medicine. Retrieved from https://www.aamc.org/download/359222/data/emergencymed.pdf . Accessed 10 May 2018.

- 20. Association of American Medical Colleges. (2019). About ERAS. Retrieved from https://students-residents.aamc.org/applying-residency/article/abouteras/

- 3. Max BA, Gelfand B, Brooks MR, Beckerly R, Segal S. Have personal statements become impersonal? An evaluation of personal statements in anesthesiology residency applications. J Clin Anesth. 2010;22(5):346–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2009.10.007. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. National Resident Matching Program. Results of the 2016 NRMP Program Director Survey. 2016 (June):79–80. http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/NRMP-2016-Program-Director-Survey.pdf . 8 June 2018

- 5. Osman NY, Schonhardt-Bailey C, Walling JL, Katz JT, Alexander EK. Textual analysis of internal medicine residency personal statements: themes and gender differences. Med Educ. 2015;49(1):93–102. doi: 10.1111/medu.12487. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Campbell BH, Havas N, Derse AR, Holloway RL. Creating a residency application personal statement writers workshop: fostering narrative, teamwork, and insight at a time of stress. Acad Med. 2016;91(3):371–375. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000863. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Glaser BGSAL. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Chicago; 1967.

- 8. Ostapenko L, Schonhardt-Bailey C, Sublette JW, Smink DS, Osman NY. Textual analysis of general surgery residency personal statements: topics and gender differences. J Surg Educ. 2018;75(3):573–581. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2017.09.021. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Dedoose. https://www.dedoose.com/ . Published 2018. Accessed June 12, 2018

- 10. Lee AG, Golnik KC, Oetting TA, Beaver HA, Boldt HC, Olson R, Greenlee E, Abramoff MD, Johnson AT, Carter K. Re-engineering the resident applicant selection process in ophthalmology: a literature review and recommendations for improvement. Surv Ophthalmol. 2008;53(2):164–176. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2007.12.007. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Nield LS, Nease EK, Mitra S, Van Den Langenberg E, Saggio RB. Major themes in the personal statements of pediatric resident applicants. Clin Pediatr. 2016;55(7):671–672. doi: 10.1177/0009922815600440. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. AAMC. 2019 AMCAS applicant guide. American Medical College Application Service. https://aamc-orange.global.ssl.fastly.net/production/media/filer_public/2d/5d/2d5d7c94-6b23-4edf-ab1b-d574221bf6e3/2019-amcas-applicant-guide.pdf . Accessed May 10, 2019

- 13. Jordan J, Linden JA, Maculatis MC, Hern HG, Jr, Schneider JI, Wills CP, Marshall JP, Friedman A, Yarris LM. Identifying the emergency medicine personality: a multisite exploratory pilot study. AEM Educ Train. 2018;2(2):91–99. doi: 10.1002/aet2.10078. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Olson DP, Oatts JT, fields BG, Huot SJ. The residency application Abyss: insights and advice. Yale J Biol Med. 2011;84(3):195–202. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Smith EA, Weyhing B, Mody Y, Smith WL. A critical analysis of personal statements submitted by radiology residency applicants. Acad Radiol. 2005;12(8):1024–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2005.04.006. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Mathur A, Kamat D. The personal statement. J Pediatr. 2014;164(4):682–682.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.01.003. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. White BAA, Sadoski M, Thomas S, Shabahang M. Is the evaluation of the personal statement a reliable component of the general surgery residency application? J Surg Educ. 2012;69(3):340–343. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2011.12.003. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Olazagasti J, Gorouhi F, Fazel N. A critical review of personal statements submitted by dermatology residency applicants. Dermatol Res Pract. 2014;2014:934874. doi: 10.1155/2014/934874. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Badal JJ, Jacobsen WK, Holt BW. Behavioral evaluations of anesthesiology residents and overuse of the first-person pronoun in personal statements. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3(2):151–154. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-10-00117.1. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (233.3 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Where to start

- Ultimate Guides

- Virtual Work Experiences

- Chat to students

- UCAS events

- Apprenticeships

Subject guides

- Subject tasters

Industry guides

Where to go.

- Universities and colleges

City guides

- Types of employment

- Write a cover letter

- Starting work

- Career quiz

Before you apply

- Campus open days

- What and where to study

- Distance learning

- Higher Technical Qualifications (HTQs)

- Studying at a college

- Pros and cons of university

Applying to university

- Dates and deadlines

Personal statement

- UCAS Tariff points

- Individual needs

After applying

- Track your application