Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

6.1 Purpose, Audience, Tone, and Content

Learning objectives.

- Identify the four common academic purposes.

- Identify audience, tone, and content.

- Apply purpose, audience, tone, and content to a specific assignment.

Imagine reading one long block of text, with each idea blurring into the next. Even if you are reading a thrilling novel or an interesting news article, you will likely lose interest in what the author has to say very quickly. During the writing process, it is helpful to position yourself as a reader. Ask yourself whether you can focus easily on each point you make. One technique that effective writers use is to begin a fresh paragraph for each new idea they introduce.

Paragraphs separate ideas into logical, manageable chunks. One paragraph focuses on only one main idea and presents coherent sentences to support that one point. Because all the sentences in one paragraph support the same point, a paragraph may stand on its own. To create longer assignments and to discuss more than one point, writers group together paragraphs.

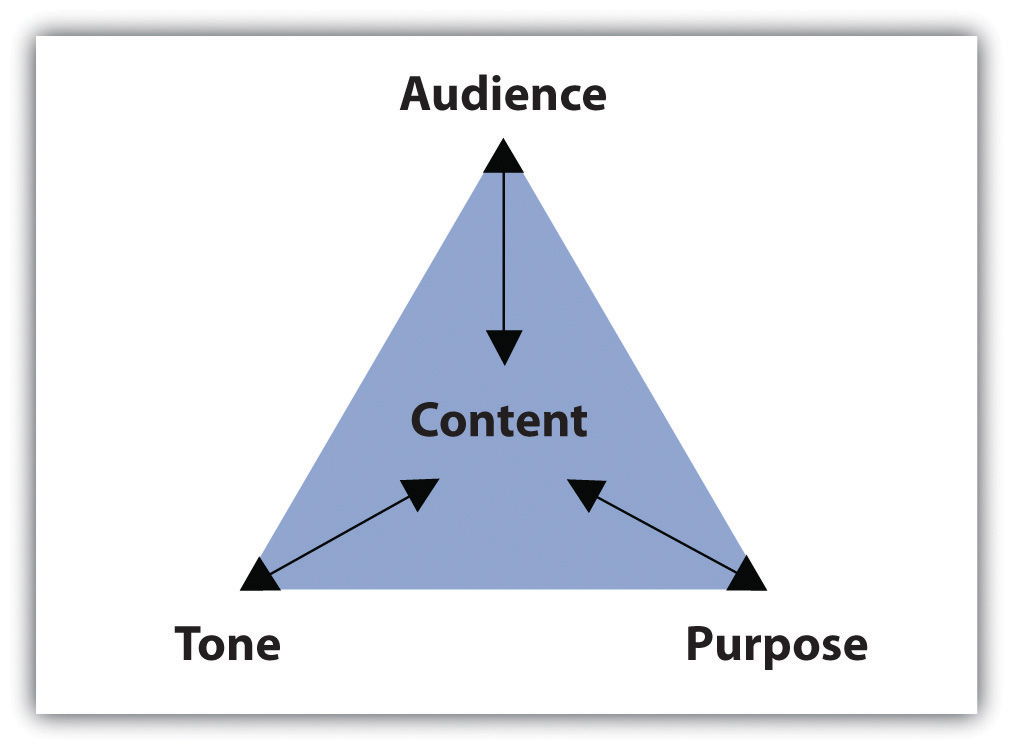

Three elements shape the content of each paragraph:

- Purpose . The reason the writer composes the paragraph.

- Tone . The attitude the writer conveys about the paragraph’s subject.

- Audience . The individual or group whom the writer intends to address.

Figure 6.1 Purpose, Audience, Tone, and Content Triangle

The assignment’s purpose, audience, and tone dictate what the paragraph covers and how it will support one main point. This section covers how purpose, audience, and tone affect reading and writing paragraphs.

Identifying Common Academic Purposes

The purpose for a piece of writing identifies the reason you write a particular document. Basically, the purpose of a piece of writing answers the question “Why?” For example, why write a play? To entertain a packed theater. Why write instructions to the babysitter? To inform him or her of your schedule and rules. Why write a letter to your congressman? To persuade him to address your community’s needs.

In academic settings, the reasons for writing fulfill four main purposes: to summarize, to analyze, to synthesize, and to evaluate. You will encounter these four purposes not only as you read for your classes but also as you read for work or pleasure. Because reading and writing work together, your writing skills will improve as you read. To learn more about reading in the writing process, see Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” .

Eventually, your instructors will ask you to complete assignments specifically designed to meet one of the four purposes. As you will see, the purpose for writing will guide you through each part of the paper, helping you make decisions about content and style. For now, identifying these purposes by reading paragraphs will prepare you to write individual paragraphs and to build longer assignments.

Summary Paragraphs

A summary shrinks a large amount of information into only the essentials. You probably summarize events, books, and movies daily. Think about the last blockbuster movie you saw or the last novel you read. Chances are, at some point in a casual conversation with a friend, coworker, or classmate, you compressed all the action in a two-hour film or in a two-hundred-page book into a brief description of the major plot movements. While in conversation, you probably described the major highlights, or the main points in just a few sentences, using your own vocabulary and manner of speaking.

Similarly, a summary paragraph condenses a long piece of writing into a smaller paragraph by extracting only the vital information. A summary uses only the writer’s own words. Like the summary’s purpose in daily conversation, the purpose of an academic summary paragraph is to maintain all the essential information from a longer document. Although shorter than the original piece of writing, a summary should still communicate all the key points and key support. In other words, summary paragraphs should be succinct and to the point.

A summary of the report should present all the main points and supporting details in brief. Read the following summary of the report written by a student:

Notice how the summary retains the key points made by the writers of the original report but omits most of the statistical data. Summaries need not contain all the specific facts and figures in the original document; they provide only an overview of the essential information.

Analysis Paragraphs

An analysis separates complex materials in their different parts and studies how the parts relate to one another. The analysis of simple table salt, for example, would require a deconstruction of its parts—the elements sodium (Na) and chloride (Cl). Then, scientists would study how the two elements interact to create the compound NaCl, or sodium chloride, which is also called simple table salt.

Analysis is not limited to the sciences, of course. An analysis paragraph in academic writing fulfills the same purpose. Instead of deconstructing compounds, academic analysis paragraphs typically deconstruct documents. An analysis takes apart a primary source (an essay, a book, an article, etc.) point by point. It communicates the main points of the document by examining individual points and identifying how the points relate to one another.

Take a look at a student’s analysis of the journal report.

Notice how the analysis does not simply repeat information from the original report, but considers how the points within the report relate to one another. By doing this, the student uncovers a discrepancy between the points that are backed up by statistics and those that require additional information. Analyzing a document involves a close examination of each of the individual parts and how they work together.

Synthesis Paragraphs

A synthesis combines two or more items to create an entirely new item. Consider the electronic musical instrument aptly named the synthesizer. It looks like a simple keyboard but displays a dashboard of switches, buttons, and levers. With the flip of a few switches, a musician may combine the distinct sounds of a piano, a flute, or a guitar—or any other combination of instruments—to create a new sound. The purpose of the synthesizer is to blend together the notes from individual instruments to form new, unique notes.

The purpose of an academic synthesis is to blend individual documents into a new document. An academic synthesis paragraph considers the main points from one or more pieces of writing and links the main points together to create a new point, one not replicated in either document.

Take a look at a student’s synthesis of several sources about underage drinking.

Notice how the synthesis paragraphs consider each source and use information from each to create a new thesis. A good synthesis does not repeat information; the writer uses a variety of sources to create a new idea.

Evaluation Paragraphs

An evaluation judges the value of something and determines its worth. Evaluations in everyday experiences are often not only dictated by set standards but also influenced by opinion and prior knowledge. For example, at work, a supervisor may complete an employee evaluation by judging his subordinate’s performance based on the company’s goals. If the company focuses on improving communication, the supervisor will rate the employee’s customer service according to a standard scale. However, the evaluation still depends on the supervisor’s opinion and prior experience with the employee. The purpose of the evaluation is to determine how well the employee performs at his or her job.

An academic evaluation communicates your opinion, and its justifications, about a document or a topic of discussion. Evaluations are influenced by your reading of the document, your prior knowledge, and your prior experience with the topic or issue. Because an evaluation incorporates your point of view and reasons for your point of view, it typically requires more critical thinking and a combination of summary, analysis, and synthesis skills. Thus evaluation paragraphs often follow summary, analysis, and synthesis paragraphs. Read a student’s evaluation paragraph.

Notice how the paragraph incorporates the student’s personal judgment within the evaluation. Evaluating a document requires prior knowledge that is often based on additional research.

When reviewing directions for assignments, look for the verbs summarize , analyze , synthesize , or evaluate . Instructors often use these words to clearly indicate the assignment’s purpose. These words will cue you on how to complete the assignment because you will know its exact purpose.

Read the following paragraphs about four films and then identify the purpose of each paragraph.

- This film could easily have been cut down to less than two hours. By the final scene, I noticed that most of my fellow moviegoers were snoozing in their seats and were barely paying attention to what was happening on screen. Although the director sticks diligently to the book, he tries too hard to cram in all the action, which is just too ambitious for such a detail-oriented story. If you want my advice, read the book and give the movie a miss.

- During the opening scene, we learn that the character Laura is adopted and that she has spent the past three years desperately trying to track down her real parents. Having exhausted all the usual options—adoption agencies, online searches, family trees, and so on—she is on the verge of giving up when she meets a stranger on a bus. The chance encounter leads to a complicated chain of events that ultimately result in Laura getting her lifelong wish. But is it really what she wants? Throughout the rest of the film, Laura discovers that sometimes the past is best left where it belongs.

- To create the feeling of being gripped in a vice, the director, May Lee, uses a variety of elements to gradually increase the tension. The creepy, haunting melody that subtly enhances the earlier scenes becomes ever more insistent, rising to a disturbing crescendo toward the end of the movie. The desperation of the actors, combined with the claustrophobic atmosphere and tight camera angles create a realistic firestorm, from which there is little hope of escape. Walking out of the theater at the end feels like staggering out of a Roman dungeon.

- The scene in which Campbell and his fellow prisoners assist the guards in shutting down the riot immediately strikes the viewer as unrealistic. Based on the recent reports on prison riots in both Detroit and California, it seems highly unlikely that a posse of hardened criminals will intentionally help their captors at the risk of inciting future revenge from other inmates. Instead, both news reports and psychological studies indicate that prisoners who do not actively participate in a riot will go back to their cells and avoid conflict altogether. Examples of this lack of attention to detail occur throughout the film, making it almost unbearable to watch.

Collaboration

Share with a classmate and compare your answers.

Writing at Work

Thinking about the purpose of writing a report in the workplace can help focus and structure the document. A summary should provide colleagues with a factual overview of your findings without going into too much specific detail. In contrast, an evaluation should include your personal opinion, along with supporting evidence, research, or examples to back it up. Listen for words such as summarize , analyze , synthesize , or evaluate when your boss asks you to complete a report to help determine a purpose for writing.

Consider the essay most recently assigned to you. Identify the most effective academic purpose for the assignment.

My assignment: ____________________________________________

My purpose: ____________________________________________

Identifying the Audience

Imagine you must give a presentation to a group of executives in an office. Weeks before the big day, you spend time creating and rehearsing the presentation. You must make important, careful decisions not only about the content but also about your delivery. Will the presentation require technology to project figures and charts? Should the presentation define important words, or will the executives already know the terms? Should you wear your suit and dress shirt? The answers to these questions will help you develop an appropriate relationship with your audience, making them more receptive to your message.

Now imagine you must explain the same business concepts from your presentation to a group of high school students. Those important questions you previously answered may now require different answers. The figures and charts may be too sophisticated, and the terms will certainly require definitions. You may even reconsider your outfit and sport a more casual look. Because the audience has shifted, your presentation and delivery will shift as well to create a new relationship with the new audience.

In these two situations, the audience—the individuals who will watch and listen to the presentation—plays a role in the development of presentation. As you prepare the presentation, you visualize the audience to anticipate their expectations and reactions. What you imagine affects the information you choose to present and how you will present it. Then, during the presentation, you meet the audience in person and discover immediately how well you perform.

Although the audience for writing assignments—your readers—may not appear in person, they play an equally vital role. Even in everyday writing activities, you identify your readers’ characteristics, interests, and expectations before making decisions about what you write. In fact, thinking about audience has become so common that you may not even detect the audience-driven decisions.

For example, you update your status on a social networking site with the awareness of who will digitally follow the post. If you want to brag about a good grade, you may write the post to please family members. If you want to describe a funny moment, you may write with your friends’ senses of humor in mind. Even at work, you send e-mails with an awareness of an unintended receiver who could intercept the message.

In other words, being aware of “invisible” readers is a skill you most likely already possess and one you rely on every day. Consider the following paragraphs. Which one would the author send to her parents? Which one would she send to her best friend?

Last Saturday, I volunteered at a local hospital. The visit was fun and rewarding. I even learned how to do cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or CPR. Unfortunately, I think caught a cold from one of the patients. This week, I will rest in bed and drink plenty of clear fluids. I hope I am well by next Saturday to volunteer again.

OMG! You won’t believe this! My advisor forced me to do my community service hours at this hospital all weekend! We learned CPR but we did it on dummies, not even real peeps. And some kid sneezed on me and got me sick! I was so bored and sniffling all weekend; I hope I don’t have to go back next week. I def do NOT want to miss the basketball tournament!

Most likely, you matched each paragraph to its intended audience with little hesitation. Because each paragraph reveals the author’s relationship with her intended readers, you can identify the audience fairly quickly. When writing your own paragraphs, you must engage with your audience to build an appropriate relationship given your subject. Imagining your readers during each stage of the writing process will help you make decisions about your writing. Ultimately, the people you visualize will affect what and how you write.

While giving a speech, you may articulate an inspiring or critical message, but if you left your hair a mess and laced up mismatched shoes, your audience would not take you seriously. They may be too distracted by your appearance to listen to your words.

Similarly, grammar and sentence structure serve as the appearance of a piece of writing. Polishing your work using correct grammar will impress your readers and allow them to focus on what you have to say.

Because focusing on audience will enhance your writing, your process, and your finished product, you must consider the specific traits of your audience members. Use your imagination to anticipate the readers’ demographics, education, prior knowledge, and expectations.

- Demographics. These measure important data about a group of people, such as their age range, their ethnicity, their religious beliefs, or their gender. Certain topics and assignments will require these kinds of considerations about your audience. For other topics and assignments, these measurements may not influence your writing in the end. Regardless, it is important to consider demographics when you begin to think about your purpose for writing.

- Education. Education considers the audience’s level of schooling. If audience members have earned a doctorate degree, for example, you may need to elevate your style and use more formal language. Or, if audience members are still in college, you could write in a more relaxed style. An audience member’s major or emphasis may also dictate your writing.

- Prior knowledge. This refers to what the audience already knows about your topic. If your readers have studied certain topics, they may already know some terms and concepts related to the topic. You may decide whether to define terms and explain concepts based on your audience’s prior knowledge. Although you cannot peer inside the brains of your readers to discover their knowledge, you can make reasonable assumptions. For instance, a nursing major would presumably know more about health-related topics than a business major would.

- Expectations. These indicate what readers will look for while reading your assignment. Readers may expect consistencies in the assignment’s appearance, such as correct grammar and traditional formatting like double-spaced lines and legible font. Readers may also have content-based expectations given the assignment’s purpose and organization. In an essay titled “The Economics of Enlightenment: The Effects of Rising Tuition,” for example, audience members may expect to read about the economic repercussions of college tuition costs.

On your own sheet of paper, generate a list of characteristics under each category for each audience. This list will help you later when you read about tone and content.

1. Your classmates

- Demographics ____________________________________________

- Education ____________________________________________

- Prior knowledge ____________________________________________

- Expectations ____________________________________________

2. Your instructor

3. The head of your academic department

4. Now think about your next writing assignment. Identify the purpose (you may use the same purpose listed in Note 6.12 “Exercise 2” ), and then identify the audience. Create a list of characteristics under each category.

My audience: ____________________________________________

Please share with a classmate and compare your answers.

Keep in mind that as your topic shifts in the writing process, your audience may also shift. For more information about the writing process, see Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” .

Also, remember that decisions about style depend on audience, purpose, and content. Identifying your audience’s demographics, education, prior knowledge, and expectations will affect how you write, but purpose and content play an equally important role. The next subsection covers how to select an appropriate tone to match the audience and purpose.

Selecting an Appropriate Tone

Tone identifies a speaker’s attitude toward a subject or another person. You may pick up a person’s tone of voice fairly easily in conversation. A friend who tells you about her weekend may speak excitedly about a fun skiing trip. An instructor who means business may speak in a low, slow voice to emphasize her serious mood. Or, a coworker who needs to let off some steam after a long meeting may crack a sarcastic joke.

Just as speakers transmit emotion through voice, writers can transmit through writing a range of attitudes, from excited and humorous to somber and critical. These emotions create connections among the audience, the author, and the subject, ultimately building a relationship between the audience and the text. To stimulate these connections, writers intimate their attitudes and feelings with useful devices, such as sentence structure, word choice, punctuation, and formal or informal language. Keep in mind that the writer’s attitude should always appropriately match the audience and the purpose.

Read the following paragraph and consider the writer’s tone. How would you describe the writer’s attitude toward wildlife conservation?

Many species of plants and animals are disappearing right before our eyes. If we don’t act fast, it might be too late to save them. Human activities, including pollution, deforestation, hunting, and overpopulation, are devastating the natural environment. Without our help, many species will not survive long enough for our children to see them in the wild. Take the tiger, for example. Today, tigers occupy just 7 percent of their historical range, and many local populations are already extinct. Hunted for their beautiful pelt and other body parts, the tiger population has plummeted from one hundred thousand in 1920 to just a few thousand. Contact your local wildlife conservation society today to find out how you can stop this terrible destruction.

Think about the assignment and purpose you selected in Note 6.12 “Exercise 2” , and the audience you selected in Note 6.16 “Exercise 3” . Now, identify the tone you would use in the assignment.

My tone: ____________________________________________

Choosing Appropriate, Interesting Content

Content refers to all the written substance in a document. After selecting an audience and a purpose, you must choose what information will make it to the page. Content may consist of examples, statistics, facts, anecdotes, testimonies, and observations, but no matter the type, the information must be appropriate and interesting for the audience and purpose. An essay written for third graders that summarizes the legislative process, for example, would have to contain succinct and simple content.

Content is also shaped by tone. When the tone matches the content, the audience will be more engaged, and you will build a stronger relationship with your readers. Consider that audience of third graders. You would choose simple content that the audience will easily understand, and you would express that content through an enthusiastic tone. The same considerations apply to all audiences and purposes.

Match the content in the box to the appropriate audience and purpose. On your own sheet of paper, write the correct letter next to the number.

- Whereas economist Holmes contends that the financial crisis is far from over, the presidential advisor Jones points out that it is vital to catch the first wave of opportunity to increase market share. We can use elements of both experts’ visions. Let me explain how.

- In 2000, foreign money flowed into the United States, contributing to easy credit conditions. People bought larger houses than they could afford, eventually defaulting on their loans as interest rates rose.

- The Emergency Economic Stabilization Act, known by most of us as the humungous government bailout, caused mixed reactions. Although supported by many political leaders, the statute provoked outrage among grassroots groups. In their opinion, the government was actually rewarding banks for their appalling behavior.

Audience: An instructor

Purpose: To analyze the reasons behind the 2007 financial crisis

Content: ____________________________________________

Audience: Classmates

Purpose: To summarize the effects of the $700 billion government bailout

Audience: An employer

Purpose: To synthesize two articles on preparing businesses for economic recovery

Using the assignment, purpose, audience, and tone from Note 6.18 “Exercise 4” , generate a list of content ideas. Remember that content consists of examples, statistics, facts, anecdotes, testimonies, and observations.

My content ideas: ____________________________________________

Key Takeaways

- Paragraphs separate ideas into logical, manageable chunks of information.

- The content of each paragraph and document is shaped by purpose, audience, and tone.

- The four common academic purposes are to summarize, to analyze, to synthesize, and to evaluate.

- Identifying the audience’s demographics, education, prior knowledge, and expectations will affect how and what you write.

- Devices such as sentence structure, word choice, punctuation, and formal or informal language communicate tone and create a relationship between the writer and his or her audience.

- Content may consist of examples, statistics, facts, anecdotes, testimonies, and observations. All content must be appropriate and interesting for the audience, purpose and tone.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Writing Clear Science

Learn to write clearly and succinctly, without sacrificing the accuracy of your topic..

How to identify your target audience

When we write, we write about something (the topic) in a certain format (the document type) for a reader or group of readers (the audience). Deciding what we are writing about and what type of document to prepare is usually straightforward for most writers. However, deciding who we are writing for is not always thoroughly considered. To a large degree, the audience of a document is determined by the type of document and the subject matter but unless researchers and other science writers have a background in marketing, the concept of identifying and catering to a target audience might not be a high priority.

DOWNLOAD THE INFOGRAPHIC ' 6 ways to identify and cater to your target audience '

Unless catering to a target audience is a central objective, your document may lack some of the fundamentals of good document design. Spending the time deciding exactly what you want to do for your audience, rather than simply delivering information, will help you fine-tune the content and the design of your document.

Problems caused by not understanding your target audience

Common writing problems often reflect that a writer has not thoroughly considered who their audience is or what they need. This can cause the following problems:

- providing too much (or not enough) detail or background information

- providing too much detail on unrelated sub-topics or on a well-known topic

- using the wrong language or unfamiliar terminology

- assuming the audience’s level of interest in, or understanding of, the topic

One common mistake in science and academic writing is assuming your audience will know your topic nearly as well as you do. The problem with this assumption is that crucial background information and explanation of fundamental concepts may be omitted. Authors of research papers will often make this assumption deliberately if they are writing about a specialised topic. Yet even in these cases, it is not a good habit to omit important background information and project details that are necessary for the reader to understand the context of the research.

Get feedback

It is easy to fall into the trap of thinking that writing is simply delivering information if you are a solo writer, if you are inexperienced or if you don’t get regular feedback on your writing. If you do get regular feedback, it might not be enough if you only get feedback from people who know your topic well as you do; your colleagues or supervisors may ensure you write a scientifically-accurate document but anyone overly-familiar with your topic may not realise that what you’ve written is not clearly written or easy to read.

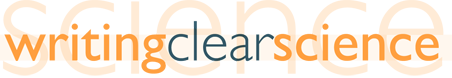

There are three different types of audiences to consider

An audience is a collective group of readers and for most purposes we need to think about our readers as a group and generalise about what qualities they have. I define three types of audience for most documents: the target audience , the secondary audience and the tertiary audience . For an example of this definition, refer to the diagram below that outlines the hypothetical audiences for an ecological research paper.

Your target audience is your intended audience. They are the group of readers that you want to read your document or you expect will read your document. These are the people you are designing your document for. Your target audience should understand everything you write. Some examples are research scientists writing peer-reviewed papers for their peers, students writing assignments for their lecturers or consultants writing reports for clients.

Your secondary audience are those people who still want, or need, to read your document but may have different education backgrounds or work within a different discipline to your target audience. For example, the secondary audience of an ecological research paper might be scientists from other disciplines, or other people interested in your topic or your project outcomes; for example, land managers, farmers, conservationists, journalists, science educators or students. Your secondary audience may not be thoroughly familiar with your topic but still has a strong or vested interest in your projects’ outcomes. However, it is not possible to cater to both your target audience and your secondary audience with the same document. You cannot cater to the secondary audience as you would need to provide too much detail or instruction, making it tiring for the target audience to read, or worse make the target audience feel the document is not designed for them.

You cannot explain everything for your secondary audience but you can help them navigate your document by defining your key terms and ensuring your main aim and findings are abundantly clear.

Your tertiary audience are people who will directly or indirectly benefit or be affected by your work in some way but will not read your document themselves; they will learn about your work either through the secondary or target audience of your document. Because your tertiary audience won’t be reading your document, it is crucial for you to ensure your key messages are abundantly clear so they are not mis-interpreted or mis-represented.

Key ways to identify and cater for your target audience

- Think about who your readers are and whether they fit into either of the three audience categories, then focus on how to cater for the target audience. Some factors to consider:

- Who will want or need to read your document? What reasons do they have for reading your document?

- Who will be interested in your topic and key findings? Why will they be interested in reading your document? If they are not already interested, how do you attract them?

- What is their occupation, expertise, background or level of education?

- Will they be able to understand all parts of your document? If not, include sufficient detail and explanation to ensure that they do or assign them to your secondary audience.

- What people need to read your document

- What task(s) will your document perform for them?

- How they will find out about your document?

- How will they access your document?

DOWNLOAD THE INFOGRAPHIC: 6 ways to identify and cater for your target audience

Once you have clearly mapped out who you are writing to and how you will cater to them. If appropriate, ask someone from your target audience to give you feedback on a late draft of your document. You might find there are some important aspects you still need to consider.

- Do not assume your readers know everything you do.

- Understand there are different types of audiences who may read your document.

- Always define your key terms and explain your key concepts.

- If appropriate, ask someone from your target audience for feedback on a late draft of you rdocument.

© Dr Marina Hurley 2020 www.writingclearscience.com.au

Any suggestions or comments please email [email protected]

Find out more about our new online course...

How to be an Efficient Science Writer

The Essentials of Sentence Structure

Now includes feedback on your writing Learn more...

SUBSCRIBE to the Writing Clear Science Newsletter

to keep informed about our latest blogs, webinars and writing courses.

F URTHER READING

- Should we use active or passive voice?

- 10 writing tips for the struggling ESL science writer

- Co-authors should define their roles and responsibilities before they start writing

- How to write when you don’t feel like it

- When to cite and when not to

- Back to basics: science knowledge is gained while information is produced

- How to build and maintain confidence as a writer

- If science was perfect, it wouldn’t be science

- What is science writing?

- 8 steps to writing your first draft

- Two ways to be an inefficient writer

- Work-procrastination: important stuff that keeps us from writing

The Importance of Audience in Student Writing

Audience is one of the most integral parts of writing regardless of an author’s skill or proficiency. Whether your students are writing a simple in-class narrative, a piece for a final exam, or a college application essay, their audience determines what kind of voice they want to convey in their compositions. It guides the intent of their writing and determines how complex or how simple the piece should be. It helps them determine what perspective is appropriate to write from, and it provides them with an understanding of what is going to either appeal to or deter their audience.

Identifying Your Audience

The first thing any writer needs to do when beginning a composition is develop a strong understanding of his or her audience. Help your students understand that their audience might be you (their teacher), their friends, their parents, or a complete stranger. Each of these different audiences will perceive what is written in a different way, so with each audience it’s key that students place themselves in the shoes of a defined audience member and think from the perspective of that individual or from the perspective of the audience as a whole.

Understanding What Appeals to Your Audience

You might explain to your students that if they are writing an essay for you, their teacher, you might review their writing for factual accuracy, sensible reasoning and structure, grammar, and a variety of other factors that indicate their technical ability in writing. However, if they are writing something that’s just going to be read by their friends, those friends probably won’t mind a few errors here or there in sentence structure. On another hand, if students are writing to persuade or convince someone, that audience needs to know why they should care. Again, if students are trying to make their audience laugh, students need to know what the audience finds funny. We’re starting to see a pattern here, right?

Questions to Answer About Your Audience

Let your students know they may have to do some thinking or even some research to determine how to craft their writing based on their audience. The following is a great list of questions for your students to ask themselves while brainstorming ideas about their audience:

- Do you only have one audience? Or are you addressing more than one kind of audience?

- What does your audience need to know ahead of time?

- What is it that your audience wants to hear? What is the most important thing to them?

- What is your audience least likely to care about?

- Can you organize your writing in a different way to better appeal to your audience?

- What are some ways in which you might persuade, surprise, or inspire your audience?

- What do you want your audience to think about you? What impression will your writing convey?

It’s really that simple in the end: If your students understand audience, they will know how to most effectively connect with them through their writing.

English Grammar 101 Alternatives

When You Ask for Analysis but You Get Summary Instead

Establishing Confident Writers Through Creativity and Self-Expression

Brainstorming Through Writer’s Block

Four Steps to Teaching Your Students Adverbs

How to Fire Your Internal Critic

What Just 10 Minutes of Daily Journaling Can Do for Student Writing

The Four Levels of Flow in Writing: What it Means When Writing Flows

Home Features Plans & Pricing Reviews

Instructional Method Blog About Contact

Login Support Request a Quote Get 30 Days Free

© GrammarFlip 2024 | All Rights Reserved | Privacy & Terms

IMAGES

VIDEO