University Library

Research Posters

What makes a great poster.

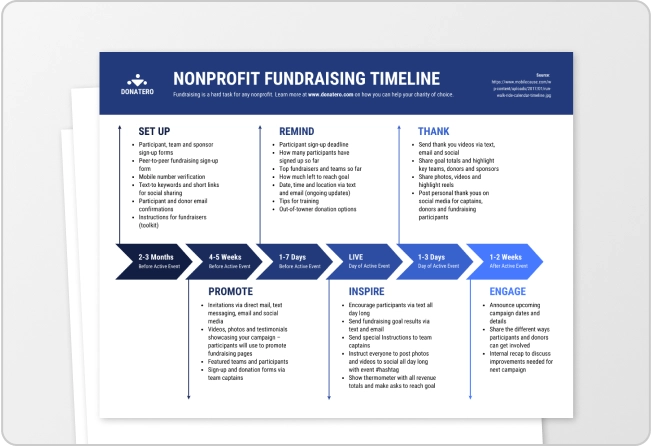

- Step by step

- Visualizations & images

- Illinois Logo

- Archiving - Grad Students

- More Resources

- Oral Presentations

- 2024 Undergraduate Research Symposium This link opens in a new window

- Colin Purrington - Designing conference posters

- The poster sessions pool - Flickr

- F1000Research Open access repository for posters and slide presentations in biology and medicine.

- Better Posters - A Blog Academic conference posters are often ugly, with tiny text, confusing layouts, and dubious colour schemes. Better Posters is about making posters informative and beautiful.

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Step by step >>

- Last Updated: Oct 29, 2024 11:53 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.illinois.edu/poster

We use essential cookies to make Venngage work. By clicking “Accept All Cookies”, you agree to the storing of cookies on your device to enhance site navigation, analyze site usage, and assist in our marketing efforts.

Manage Cookies

Cookies and similar technologies collect certain information about how you’re using our website. Some of them are essential, and without them you wouldn’t be able to use Venngage. But others are optional, and you get to choose whether we use them or not.

Strictly Necessary Cookies

These cookies are always on, as they’re essential for making Venngage work, and making it safe. Without these cookies, services you’ve asked for can’t be provided.

Show cookie providers

- Google Login

Functionality Cookies

These cookies help us provide enhanced functionality and personalisation, and remember your settings. They may be set by us or by third party providers.

Performance Cookies

These cookies help us analyze how many people are using Venngage, where they come from and how they're using it. If you opt out of these cookies, we can’t get feedback to make Venngage better for you and all our users.

- Google Analytics

Targeting Cookies

These cookies are set by our advertising partners to track your activity and show you relevant Venngage ads on other sites as you browse the internet.

- Google Tag Manager

- Infographics

- Daily Infographics

- Popular Templates

- Accessibility

- Graphic Design

- Graphs and Charts

- Data Visualization

- Human Resources

- Beginner Guides

Blog Data Visualization 12 Scientific Poster Examples [And How To Create One]

12 Scientific Poster Examples [And How To Create One]

Written by: Ivonna Cabrera Jul 02, 2023

Truth be told, scientific posters are effective at piquing interest. It’s incredible how graphics and presentation style can attract audiences.

Want to make a scientific poster but don’t know how? Well, you no longer need to be a design guru if you use Venngage’s Poster Maker .

You can speed up the process even more by using our scientific poster templates.

Before I dive right into scientific poster examples, let’s discuss what scientific posters are in the first place.

Click to jump ahead:

What is a scientific poster?

Best examples of scientific posters, how to create a scientific poster, what makes a good scientific poster.

- What you need to make a scientific poster

- What’s the purpose of a scientific or research poster?

A scientific poster is a visual presentation of research findings or scientific information shared with audiences at conferences, symposiums, and academic events. Scientific posters generally provide information on topics their authors are currently discussing.

Many scientists, researchers and medical experts use scientific posters to explain their findings in a simple and easy-to-understand format.

Of course, text isn’t the best way to show how scientific posters work.

So, I’ll let these examples do the talking.

Academic scientific poster examples

An academic scientific poster presents complicated information in a visually appealing manner.

Choosing the right poster layout is important here. Generally, sections such as an introduction, use, process, and takeaways allow students to understand a process or concept in a step-by-step method.

Here’s a great example of a scientific poster that discusses distillation:

Just so you know, some of our scientific poster templates are free to use and some require a small monthly fee. Sign up is always free, as is access to Venngage’s online drag-and-drop editor.

Often, it’s also important to separate information into categories and develop data in a clear and concise manner.

Is your scientific poster focused on environmental issues? Explore our gallery of environmental poster templates for inspiration and designs tailored to your topic.

Chemistry poster examples

Chemistry posters play a vital role in the scientific community by highlighting the importance of chemistry as a subject.

They also promote a deeper understanding of its principles and applications.

Here’s a great example:

A chemistry poster is usually organized in a logical and structured manner to effectively convey information.

Here are some common elements you can find in chemistry posters:

- Introduction

Here’s another example of a chemistry poster that displays only the abstract to hook the reader.

Lab poster examples

Lab posters are effective at sharing scientific knowledge, promoting discussion and collaboration, and disseminating research findings.

They provide a visual platform to showcase research efforts and contribute to the advancement of scientific knowledge in various fields of study.

In the lab poster below, the impact of overeating and binge drinking on the health of college students is presented in a format that anyone can understand the takeaway in a single glance.

Now that you know everything about scientific posters, it’s time to create your own.

Step 1 – Sign up for a free Venngage account

Start the process by signing up for Venngage with your email, Gmail or Facebook account.

Step 2 – Select a template from our library

Besides the examples above, you’ll find a sizeable collection of poster templates and specifically scientific posters to choose from.

There’s a template for every need, from a scientific poster for a case study review to templates focused on presenting complex data.

Step 3 – Edit your scientific poster with our editor

All our scientific poster templates can be edited using a simple drag-and-drop interface.

Feel free to change the colors, text, icons, or illustrations to make the design your own or simply input your data to have an optimized scientific poster in minutes.

Step 4 – Bring your scientific poster to life with icons, illustrations and branding elements

Venngage offers 40,000 icons and illustrations to help you visualize and bring a scientific poster to life.

If you upgrade to a Business account, you can also enjoy My Brand Kit — the one-click branding kit that lets you upload your logo and apply brand colors and fonts to any design.

Step 5 – Share a link to your scientific poster or upgrade to download

Once you upgrade to a Business account, you can download your scientific poster as a PNG, PDF, or interactive PDF.

But you can always share your scientific poster online for free.

Searching for a tech poster template? Explore these tech poster designs for useful and innovative templates.

A good scientific poster is often an attractive and easy-to-read presentation of scientific research .

They may include images, diagrams, graphs and tables, and they often focus on one or two main points.

Combining data and design together makes it easy for readers to dissect information easily, thanks to an attention-grabbing layout, simplified language and easy-to-follow jargon explanations where necessary.

A lot of layouts allow you to prioritize information and separate it into circles or boxes, like in the template above.

This type of poster design allows the reader to consume less time when reading the full context of a situation.

What do you need to make a useful scientific poster?

This is the section you’ve been waiting for — the best way to make a scientific poster from scratch.

Read on to learn about the steps below, and they come with easy-to-follow examples, too.

Study good scientific or academic poster examples

Venngage has great scientific poster templates for your first scientific poster. You can customize these templates using Venngage’s drag-and-drop editor.

Let’s take a look at each of them below.

The sparse but surgically precise use of text here contrasts the lush use of plants to explain photosynthesis.

Short explanations can be accompanied by explainer text in corner resource boxes that discuss the other details of photosynthesis.

Good science poster examples are readable from 10 feet away

There are many reasons why posters should be readable from 10 feet away.

The main reason is to allow readers to fully understand the concept from where they stand or walk.

For example, in a school or office hall, bulletin boards are usually 5 to 10 feet away from potential viewers. A poster that can be viewed within this range entices the audience to come closer and read the details.

School posters effectively engage students by presenting visual content that reinforces learning objectives or communicates important information. Browse our collection of school poster templates for inspiration and ideas.

The second reason is to allow readers to quickly comprehend the poster.

People usually don’t have time to stop and read a poster. In a school or office, everyone’s walking to do something urgently.

Thus, you don’t want to take up too much of your time reading jargon and difficult concepts that even academic peers can take hours to read and interpret.

Being readable from 10 feet away makes it easy for readers to understand your research.

You can use varying font sizes to create great posters. For digital campaigns, make sure that your posters are suitable for modern browsers.

Venngage’s My Brand Kit feature allows you to create posters that help your audience understand valuable info.

This is a special tool for Business accounts that allows you to upload logos, choose fonts, and set color palettes to your scientific posters .

Use our real-time collaboration feature to invite team members and work together. You can also leave comments and get feedback instantly.

Alternatively, share your design online, on social media, or via email completely for free.

Make an attention-grabbing, short headline

Attention-grabbing headlines are easy for science articles and posters.

It’s always thrilling to find out about a new plant species or discoveries that debunk old theories.

It’s a good idea to use best practices in making attention-grabbing headlines, even if it is just casual scientific content for social media.

Titles that draw attention and engagement include:

- Trending topics Create headlines according to what is trending. For example, if your study discusses climate change , align your headline to this topic to engage readers.

- Controversial developments An old textbook fact being false is a controversial and surprising topic which you can easily sum up in a headline.

- Issues that address curiosity Humans are naturally curious, so tickling the audience’s curiosity is a great way to create a compelling and attention-grabbing headline.

Use bullets and numbering to make a list easier to read

Bullets, lists and clear language are all tools that improve readability.

Even without fancy graphics and poster backgrounds , a short-sentence, simple-worded post with bullets and lists makes it easy to understand any topic.

Bulleted lists make each subtopic of your scientific poster easy to read. Plus, it allows readers to jump from one subtopic to another without feeling like they missed information along the way.

Designers of scientific posters find it easier to design bulleted and list content because they can place every bullet in different sections, making the poster easy to read.

If you used bullets instead of boxes to explain each subtopic in this poster, you could still read it easily — just not from 10 feet away.

Ensure layout consistency

Layout consistency is the uniform appearance of elements within a design.

It is achieved by employing the same layout, color and typography throughout an entire design.

For example, if a web page uses a consistent layout, each page will be uniform in appearance but not necessarily in content.

Layout consistency is achieved by employing the same pattern, color and typography throughout an entire design. This uniform appearance helps readers navigate for better organization.

Creating layout consistency is of crucial importance in scientific poster design because coherence creates a familiar mood and attachment for readers.

This template uses the same fonts and complementary colors that give the scientific poster its own coherent, attention-grabbing and informative personality

Related: Stay ahead of graphic design trends that can help you with your scientific poster design!

Include acknowledgments, names and affiliations

Lastly, all scientific posters include their acknowledgments, researcher names and affiliations underneath the poster.

You can use a footnote to include these details or a resource box. Plus, if you used any links as references in your research, add them to this section.

If you were the researcher involved in this scientific poster , you could include all the information I’ve mentioned underneath the last paragraph using a line to indicate that they are acknowledgments and author information.

Searching for a research poster? Browse through our collection of research poster templates in to get started!

What is the purpose of a scientific poster?

Academics are the only ones who can read and understand a technical scientific paper.

To a normal reader, a research paper’s language and syntax are challenging. Scientific papers don’t prioritize reading flow in their outlines or exposition of data, methods and results.

But with a well-made and creative poster , reading a technical paper becomes easier.

For example, effective scientific posters include images that explain complicated terms.

At the same time, the poster layout makes data and text easy to read. Lastly, scientific posters use simple language that allows even young children to understand concepts.

FAQ about scientific posters

I know you’re all set to make your own designs, but you might want to have these questions answered too.

What should a scientific poster include?

A scientific poster should include an easy-to-follow layout, graphics and color schemes that don’t take away from the reading experience. Successful scientific posters also use short sentences, simple language and bullet points.

How do you write a good scientific poster?

Researchers must focus on the evidence behind the research. Afterward, they can concentrate on using simple language and short sentences to explain their point. Short text and simple words make it easier for graphic designers to create posters with an intuitive layout.

How do you write a scientific title for a poster?

Focus on aligning your title with human emotions and curiosity. Outside human emotions, you can align your titles toward controversial or trending issues. This article dedicates an entire section to writing a great scientific title for a poster, so you should head there to learn more!

Our Poster Maker guarantees that you’ll make the most intuitive and well-designed scientific posters in a single session.

Make the best scientific posters within minutes today!

Now, you’re ready to make your own scientific posters for print or website use!

If you’re short on ideas, you can use Venngage’s scientific poster templates for inspiration. Besides access to scores of templates, you also get a free drag-and-drop web-based editor by signing up for a FREE Venngage account today. Register now!

Discover popular designs

Infographic maker

Brochure maker

White paper online

Newsletter creator

Flyer maker

Timeline maker

Letterhead maker

Mind map maker

Ebook maker

IMAGES

VIDEO