- Mathematicians

- Math Lessons

- Square Roots

- Math Calculators

MEDIEVAL MATHEMATICS

During the centuries in which the Chinese , Indian and Islamic mathematicians had been in the ascendancy, Europe had fallen into the Dark Ages, in which science, mathematics and almost all intellectual endeavour stagnated.

Scholastic scholars only valued studies in the humanities, such as philosophy and literature, and spent much of their energies quarrelling over subtle subjects in metaphysics and theology, such as “ How many angels can stand on the point of a needle? “

From the 4th to 12th Centuries, European knowledge and study of arithmetic, geometry, astronomy and music was limited mainly to Boethius’ translations of some of the works of ancient Greek masters such as Nicomachus and Euclid . All trade and calculation was made using the clumsy and inefficient Roman numeral system, and with an abacus based on Greek and Roman models.

By the 12th Century , though, Europe , and particularly Italy, was beginning to trade with the East, and Eastern knowledge gradually began to spread to the West. Robert of Chester translated Al-Khwarizmi ‘s important book on algebra into Latin in the 12th Century, and the complete text of Euclid ‘s “Elements” was translated in various versions by Adelard of Bath, Herman of Carinthia and Gerard of Cremona. The great expansion of trade and commerce in general created a growing practical need for mathematics, and arithmetic entered much more into the lives of common people and was no longer limited to the academic realm.

The advent of the printing press in the mid-15th Century also had a huge impact. Numerous books on arithmetic were published for the purpose of teaching business people computational methods for their commercial needs and mathematics gradually began to acquire a more important position in education.

Europe’s first great medieval mathematician was the Italian Leonardo of Pisa , better known by his nickname Fibonacci . Although best known for the so-called Fibonacci Sequence of numbers, perhaps his most important contribution to European mathematics was his role in spreading the use of the Hindu-Arabic numeral system throughout Europe early in the 13th Century, which soon made the Roman numeral system obsolete, and opened the way for great advances in European mathematics.

An important (but largely unknown and underrated) mathematician and scholar of the 14th Century was the Frenchman Nicole Oresme. He used a system of rectangular coordinates centuries before his countryman René Descartes popularized the idea, as well as perhaps the first time-speed-distance graph. Also, leading from his research into musicology, he was the first to use fractional exponents, and also worked on infinite series, being the first to prove that the harmonic series 1 ⁄ 1 + 1 ⁄ 2 + 1 ⁄ 3 + 1 ⁄ 4 + 1 ⁄ 5 … is a divergent infinite series (i.e. not tending to a limit, other than infinity).

The German scholar Regiomontatus was perhaps the most capable mathematician of the 15th Century , his main contribution to mathematics being in the area of trigonometry. He helped separate trigonometry from astronomy, and it was largely through his efforts that trigonometry came to be considered an independent branch of mathematics. His book “ De Triangulis “, in which he described much of the basic trigonometric knowledge which is now taught in high school and college, was the first great book on trigonometry to appear in print.

Mention should also be made of Nicholas of Cusa (or Nicolaus Cusanus), a 15th Century German philosopher, mathematician and astronomer, whose prescient ideas on the infinite and the infinitesimal directly influenced later mathematicians like Gottfried Leibniz and Georg Cantor . He also held some distinctly non-standard intuitive ideas about the universe and the Earth’s position in it, and about the elliptical orbits of the planets and relative motion, which foreshadowed the later discoveries of Copernicus and Kepler.

Study at Cambridge

About the university, research at cambridge.

- Undergraduate courses

- Events and open days

- Fees and finance

- Postgraduate courses

- How to apply

- Postgraduate events

- Fees and funding

- International students

- Continuing education

- Executive and professional education

- Courses in education

- How the University and Colleges work

- Term dates and calendars

- Visiting the University

- Annual reports

- Equality and diversity

- A global university

- Public engagement

- Give to Cambridge

- For Cambridge students

- For our researchers

- Business and enterprise

- Colleges & departments

- Email & phone search

- Museums & collections

- Student information

Department of History and Philosophy of Science

- About the Department overview

- How to find the Department

- Annual Report

- HPS Discussion email list

- Becoming a Visiting Scholar or Visiting Student overview

- Visitor fee payment

- Becoming an Affiliate

- Applying for research grants and post-doctoral fellowships

- Administration overview

- Information for new staff

- Information for examiners and assessors overview

- Operation of the HPS plagiarism policy

- Information for supervisors overview

- Supervising Part IB and Part II students

- Supervising MPhil and Part III students

- Supervising PhD students

- People overview

- Teaching Officers

- Research Fellows and Teaching Associates

- Professional Services Staff

- PhD Students

- Research overview

- Research projects overview

- Natural History in the Age of Revolutions, 1776–1848

- In the Shadow of the Tree: The Diagrammatics of Relatedness as Scientific, Scholarly and Popular Practice

- The Many Births of the Test-Tube Baby

- Culture at the Macro-Scale: Boundaries, Barriers and Endogenous Change

- Making Climate History overview

- Project summary

- Workstreams

- Works cited and project literature

- Histories of Artificial Intelligence: A Genealogy of Power overview

- From Collection to Cultivation: Historical Perspectives on Crop Diversity and Food Security overview

- Call for papers

- How Collections End: Objects, Meaning and Loss in Laboratories and Museums

- Tools in Materials Research

- Epsilon: A Collaborative Digital Framework for Nineteenth-Century Letters of Science

- Contingency in the History and Philosophy of Science

- Industrial Patronage and the Cold War University

- FlyBase: Communicating Drosophila Genetics on Paper and Online, 1970–2000

- The Lost Museums of Cambridge Science, 1865–1936

- From Hansa to Lufthansa: Transportation Technologies and the Mobility of Knowledge in Germanic Lands and Beyond, 1300–2018

- Medical Publishers, Obscenity Law and the Business of Sexual Knowledge in Victorian Britain

- Kinds of Intelligence

- Varieties of Social Knowledge

- The Vesalius Census

- Histories of Biodiversity and Agriculture

- Investigating Fake Scientific Instruments in the Whipple Museum Collection

- Before HIV: Homosex and Venereal Disease, c.1939–1984

- The Casebooks Project

- Generation to Reproduction

- The Darwin Correspondence Project

- History of Medicine overview

- Events overview

- Past events

- Philosophy of Science overview

- Study HPS overview

- Undergraduate study overview

- Introducing History and Philosophy of Science

- Frequently asked questions

- Routes into History and Philosophy of Science

- Part II overview

- Distribution of Part II marks

- BBS options

- Postgraduate study overview

- Why study HPS at Cambridge?

- MPhil in History and Philosophy of Science and Medicine overview

- A typical day for an MPhil student

- MPhil in Health, Medicine and Society

- PhD in History and Philosophy of Science overview

- Part-time PhD

PhD placement record

- Funding for postgraduate students

- Student information overview

- Timetable overview

- Primary source seminars

- Research methods seminars

- Writing support seminars

- Dissertation seminars

- BBS Part II overview

- Early Medicine

- Modern Medicine and Biomedical Sciences

- Philosophy of Science and Medicine

- Ethics of Medicine

- Philosophy and Ethics of Medicine

- Part III and MPhil

- Single-paper options

- Part IB students' guide overview

- About the course

- Supervisions

- Libraries and readings

- Scheme of examination

- Part II students' guide overview

- Primary sources

- Dissertation

- Key dates and deadlines

- Advice overview

- Examination advice

- Learning strategies and exam skills

- Advice from students

- Part III students' guide overview

- Essays and dissertation

- Subject areas

- MPhil students' guide overview

- PhD students' guide overview

- Welcome to new PhDs

- Registration exercise and annual reviews

- Your supervisor and advisor

- Progress log

- Intermission and working away from Cambridge

- The PhD thesis

- Submitting your thesis

- Examination

- News and events overview

- Seminars and reading groups overview

- Departmental Seminars

- Coffee with Scientists

- Cabinet of Natural History overview

- Publications

- History of Medicine Seminars

- Purpose and Progress in Science

- The Anthropocene

- Calculating People

- Measurement Reading Group

- Teaching Global HPSTM

- Pragmatism Reading Group

- Foundations of Physics Reading Group

- History of Science and Medicine in Southeast Asia

- Atmospheric Humanities Reading Group

- Values in Science Reading Group

- HPS Workshop

- Postgraduate Seminars overview

- Images of Science

- Language Groups overview

- Latin Therapy overview

- Bibliography of Latin language resources

- Fun with Latin

- Archive overview

- Lent Term 2024

- Michaelmas Term 2023

- Easter Term 2023

- Lent Term 2023

- Michaelmas Term 2022

- Easter Term 2022

- Lent Term 2022

- Michaelmas Term 2021

- Easter Term 2021

- Lent Term 2021

- Michaelmas Term 2020

- Easter Term 2020

- Lent Term 2020

- Michaelmas Term 2019

- Easter Term 2019

- Lent Term 2019

- Michaelmas Term 2018

- Easter Term 2018

- Lent Term 2018

- Michaelmas Term 2017

- Easter Term 2017

- Lent Term 2017

- Michaelmas Term 2016

- Easter Term 2016

- Lent Term 2016

- Michaelmas Term 2015

- Postgraduate and postdoc training overview

- Induction sessions

- Academic skills and career development

- Print & Material Sources

- Other events and resources

Medieval and early modern mathematics

- About the Department

- News and events

Jacqueline Stedall

There is much fascinating material to be explored in the history of medieval and early modern mathematics, but perhaps the first thing to be aware of it is that, particularly for the earlier centuries, almost all original sources are in Latin. Mathematical Latin uses a specialised but relatively limited vocabulary, and if you know some Latin already (A-level or a good GCSE, say) you can build on it, but if you have none you will need to devote time to learning it.

Medieval mathematics (roughly 1100–1500)

Medieval mathematics was on the whole far removed from anything that we think of as mathematics today. Indeed to study this period at all you need to be prepared to enter a world whose preconceptions, political, religious, or mathematical, were very different from our own. There are texts that are recognisably devoted to arithmetic, geometry, or occasionally algebra, but most of the writings that were later described as 'mathematical' were concerned with astrology and astronomy (the distinction between the two was often blurred). Others border on philosophy, natural philosophy (or early science), and even theology.

The main centres for such studies in northern Europe were Paris and Oxford, and Oxford still holds major collections of medieval manuscripts, many with mathematical content. This has not been a major area of study in the last few years, but for useful introductory material and overviews see the following.

- Grant, Edward, (ed), A source book in medieval science , Harvard University Press, 1974.

- Molland, George, 'Mathematics', in David C Lindberg and Ronald L Numbers (eds), Cambridge history of science , II, Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- North, J D, Chaucer's universe , Clarendon Press, 1988.

- North, J D, 'Astronomy and mathematics' and 'Natural philosophy in late medieval Oxford', in J I Catto and T A Evans, The history of the University of Oxford , II, Clarendon Press, 1992.

- North, J D, 'Medieval Oxford', in Fauvel, Flood and Wilson, Oxford figures: 800 years of the mathematical sciences , Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Stedall, Jacqueline, 'How algebra was entertained and cultivated in Europe' in Stedall, A discourse concerning algebra , Oxford University Press, 2002, 19–54.

Early modern mathematics (roughly 1500–1700)

Like all other areas of intellectual activity in the sixteenth century, mathematics was revitalized by the translation of Classical texts from Greek to Latin. It was further stimulated by the absorption of ideas from Islamic sources, and by the new technical challenges posed by increased trade and navigation. During the seventeenth century in particular, mathematics in western Europe began to change rapidly and dramatically. At the beginning of that century, mathematicians looked back on ancient learning as something they could barely hope to emulate. By the end of it, they had far outstripped Classical achievements in both methods and results, and had developed their own tools and language, recognisably similar to those we use today. The most notable mathematical advances of the seventeenth century were the development of analytical geometry, the new acceptance of indivisibles, the discovery and use of infinite series, the discovery of the calculus, and the beginnings of a mathematical interpretation of nature. All of these changes were continued, consolidated, and argued about during the eighteenth century.

At the same time, mathematical learning was becoming more widespread, and the number of publications increased rapidly. In recent years the availability of electronic databases and searchable text has transformed research possibilities for this period. Every book published in England in the seventeenth century is now catalogued, and usually digitally available, on a database known as EEBO (Early English Books Online). Its eighteenth-century counterpart is ECCO (Eighteenth Century Collections Online). Access to these is available only through academic libraries, but they are an excellent way to begin to explore the literature.

Accounts of the early modern period are to be found in all general histories of mathematics, and you should read as many as you can. The following more specialised bibliography, by no means exhaustive, is intended to illustrate just some of the different ideas, approaches, and research methods that are to be found in recent literature.

- Bos, Henk, Redefining geometrical exactness: Descartes' transformation of the early modern concept of construction , Springer, 2001.

- Feingold, Mordechai, The mathematician's apprenticeship: science, universities and society in England 1560–1640 , Cambridge University Press, 1984.

- Feingold Mordechai, 'Decline and fall: Arabic science in seventeenth-century England' in F Jamil Ragep and Sally P Ragep (eds), Tradition, transmission, transformation , Leiden: Brill, 1996, 441–469.

- Feingold Mordechai, 'Gresham College and London practitioners: the nature of the English mathematical community', in Francis Ames-Lewis (ed), Sir Thomas Gresham and Gresham College: studies in the intellectual history of London in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries , Ashgate, 1999, 174–188.

- Guicciardini, Niccolo, '"Gigantic implements of war": images of Newton as a mathematician', in E Robson and J Stedall (eds), Oxford Handbook of the History of Mathematics , Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Hill, Katherine, 'Juglers or Schollers?: negotiating the role of a mathematical practitioner', British Journal for the History of Science , 31 (1998), 253–274.

- Mahoney, Michael Sean, 1973, The mathematical career of Pierre de Fermat 1601–1665 , Princeton University Press, 1973, reprinted, 1994.

- Malcolm, Noel, and Stedall, Jacqueline, John Pell (1611–1685) and his correspondence with Sir Charles Cavendish: the mental world of an early modern mathematician , Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Stedall, Jacqueline, A discourse concerning algebra: English algebra to 1685 , Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Stedall, Jacqueline, 'Symbolism, combinations, and visual imagery in the mathematics of Thomas Harriot', Historia mathematica , 34 (2007).

- Wardhaugh, Benjamin, 'Poor Robin and Merry Andrew: mathematical humour in Restoration England', BSHM Bulletin , 23 (2007).

Email search

Privacy and cookie policies

Study History and Philosophy of Science

Undergraduate study

Postgraduate study

Library and Museum

Whipple Library

Whipple Museum

Museum Collections Portal

Research projects

History of Medicine

Philosophy of Science

© 2024 University of Cambridge

- Contact the University

- Accessibility

- Freedom of information

- Privacy policy and cookies

- Statement on Modern Slavery

- Terms and conditions

- University A-Z

- Undergraduate

- Postgraduate

- Research news

- About research at Cambridge

- Spotlight on...

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Essays on early medieval mathematics : the Latin tradition

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

obscured text on back cover page

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

Better World Books

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station35.cebu on October 14, 2021

History of medieval mathematics

- Most Cited Papers

- Most Downloaded Papers

- Newest Papers

- Save to Library

- Last »

- History of Arabic Mathematics Follow Following

- Mathematics Teacher Education Follow Following

- History of Mathematics Follow Following

- History Of Science In Islam Follow Following

- History of Algebra Follow Following

- Calculs Des Structures Mécaniques Follow Following

- History of Ottoman Science Follow Following

- The history of mathematics Follow Following

- History of Islamic science Follow Following

- Islamic History and Muslim Civilization Follow Following

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- Academia.edu Publishing

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Math Careers

Search form

- MAA Centennial

- Spotlight: Archives of American Mathematics

- MAA Officers

- MAA to the Power of New

- Council and Committees

- MAA Code of Conduct

- Policy on Conflict of Interest

- Statement about Conflict of Interest

- Recording or Broadcasting of MAA Events

- Policy for Establishing Endowments and Funds

- Avoiding Implicit Bias

- Copyright Agreement

- Principal Investigator's Manual

- Planned Giving

- The Icosahedron Society

- Our Partners

- Advertise with MAA

- Employment Opportunities

- Staff Directory

- 2022 Impact Report

- In Memoriam

- Membership Categories

- Become a Member

- Membership Renewal

- MERCER Insurance

- MAA Member Directories

- New Member Benefits

- The American Mathematical Monthly

- Mathematics Magazine

- The College Mathematics Journal

- How to Cite

- Communications in Visual Mathematics

- About Convergence

- What's in Convergence?

- Convergence Articles

- Mathematical Treasures

- Portrait Gallery

- Paul R. Halmos Photograph Collection

- Other Images

- Critics Corner

- Problems from Another Time

- Conference Calendar

- Guidelines for Convergence Authors

- Math Horizons

- Submissions to MAA Periodicals

- Guide for Referees

- Scatterplot

- Math Values

- MAA Book Series

- MAA Press (an imprint of the AMS)

- MAA Library Recommendations

- Additional Sources for Math Book Reviews

- About MAA Reviews

- Mathematical Communication

- Information for Libraries

- Author Resources

- MAA MathFest

- Proposal and Abstract Deadlines

- MAA Policies

- Invited Paper Session Proposals

- Contributed Paper Session Proposals

- Panel, Poster, Town Hall, and Workshop Proposals

- Minicourse Proposals

- MAA Section Meetings

- Virtual Programming

- Joint Mathematics Meetings

- Calendar of Events

- MathFest Programs Archive

- MathFest Abstract Archive

- Historical Speakers

- Information for School Administrators

- Information for Students and Parents

- Registration

- Getting Started with the AMC

- AMC Policies

- AMC Administration Policies

- Important AMC Dates

- Competition Locations

- Invitational Competitions

- Putnam Competition Archive

- AMC International

- Curriculum Inspirations

- Sliffe Award

- MAA K-12 Benefits

- Mailing List Requests

- Statistics & Awards

- Submit an NSF Proposal with MAA

- MAA Distinguished Lecture Series

- Common Vision

- CUPM Curriculum Guide

- Instructional Practices Guide

- Möbius MAA Placement Test Suite

- META Math Webinar May 2020

- Progress through Calculus

- Survey and Reports

- "Camp" of Mathematical Queeries

- DMEG Awardees

- National Research Experience for Undergraduates Program (NREUP)

- Neff Outreach Fund Awardees

- Tensor SUMMA Grants

- Tensor Women & Mathematics Grants

- Grantee Highlight Stories

- "Best Practices" Statements

- CoMInDS Summer Workshop 2023

- MAA Travel Grants for Project ACCCESS

- 2024 Summer Workshops

- Minority Serving Institutions Leadership Summit

- Previous Workshops

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Course Resources

- Industrial Math Case Studies

- Participating Faculty

- 2020 PIC Math Student Showcase

- Previous PIC Math Workshops on Data Science

- Dates and Locations

- Past Programs

- Leadership Team

- Support Project NExT

- Section NExT

- Section Officers Meeting History

- Preparations for Section Meetings

- Bylaws Template

- Editor Lectures Program

- MAA Section Lecturer Series

- Officer Election Support

- Section Awards

- Section Liaison Programs

- Section Visitors Program

- Expense Reimbursement

- Guidelines for Bylaw Revisions

- Guidelines for Local Arrangement Chair and/or Committee

- Guidelines for Section Webmasters

- MAA Logo Guidelines

- MAA Section Email Policy

- Section Newsletter Guidelines

- Statement on Federal Tax ID and 501(c)3 Status

- Communication Support

- Guidelines for the Section Secretary and Treasurer

- Legal & Liability Support for Section Officers

- Section Marketing Services

- Section in a Box

- Subventions and Section Finances

- Web Services

- Joining a SIGMAA

- Forming a SIGMAA

- History of SIGMAA

- SIGMAA Officer Handbook

- MAA Connect

- Meetings and Conferences for Students

- Opportunities to Present

- Information and Resources

- MAA Undergraduate Student Poster Session

- Undergraduate Research Resources

- MathFest Student Paper Sessions

- Research Experiences for Undergraduates

- Student Poster Session FAQs

- High School

- A Graduate School Primer

- Reading List

- Student Chapters

- Awards Booklets

- Carl B. Allendoerfer Awards

- Regulations Governing the Association's Award of The Chauvenet Prize

- Trevor Evans Awards

- Paul R. Halmos - Lester R. Ford Awards

- Merten M. Hasse Prize

- George Pólya Awards

- David P. Robbins Prize

- Beckenbach Book Prize

- Euler Book Prize

- Daniel Solow Author’s Award

- Henry L. Alder Award

- Deborah and Franklin Tepper Haimo Award

- Certificate of Merit

- Gung and Hu Distinguished Service

- JPBM Communications Award

- Meritorious Service

- MAA Award for Inclusivity

- T. Christine Stevens Award

- Dolciani Award Guidelines

- Morgan Prize Information

- Selden Award Eligibility and Guidelines for Nomination

- Selden Award Nomination Form

- AMS-MAA-SIAM Gerald and Judith Porter Public Lecture

- Etta Zuber Falconer

- Hedrick Lectures

- James R. C. Leitzel Lecture

- Pólya Lecturer Information

- Putnam Competition Individual and Team Winners

- D. E. Shaw Group AMC 8 Awards & Certificates

- Maryam Mirzakhani AMC 10 A Awards & Certificates

- Two Sigma AMC 10 B Awards & Certificates

- Jane Street AMC 12 A Awards & Certificates

- Akamai AMC 12 B Awards & Certificates

- High School Teachers

- MAA Social Media

You are here

- The Mathematical Cultures of Medieval Europe - Introduction

Mathematics in medieval Europe was not just the purview of scholars who wrote in Latin, although certainly the most familiar of the mathematicians of that period did write in that language, including Leonardo of Pisa, Thomas Bradwardine, and Nicole Oresme. These authors – and many others – were part of the Latin Catholic culture that was dominant in Western Europe during the Middle Ages. Yet there were two other European cultures that produced mathematics in that time period, the Hebrew culture found mostly in Spain, southern France, and parts of Italy, and the Islamic culture that predominated in Spain through the thirteenth century and, in a smaller geographic area, until its ultimate demise at the end of the fifteenth century. These two cultures had many relationships with the dominant Latin Catholic culture, but also had numerous distinct features. In fact, in many areas of mathematics, Hebrew and Arabic speaking mathematicians outshone their Latin counterparts. In what follows, we will consider several mathematicians from each of these three mathematical cultures and consider how the culture in which each lived influenced the mathematics they studied.

We begin by clarifying the words “medieval Europe”, because the dates for the activities of these three cultures vary considerably. Catholic Europe, from the fall of the Western Roman Empire up until the mid-twelfth century, had very little mathematical activity, in large measure because most of the heritage of ancient Greece had been lost. True, there was some education in mathematics in the monasteries and associated schools – as Charlemagne, first Holy Roman Emperor, had insisted – but the mathematical level was very low, consisting mainly of arithmetic and very elementary geometry. Even Euclid’s Elements were essentially unknown. About the only mathematics that was carried out was that necessary for the computation of the date of Easter.

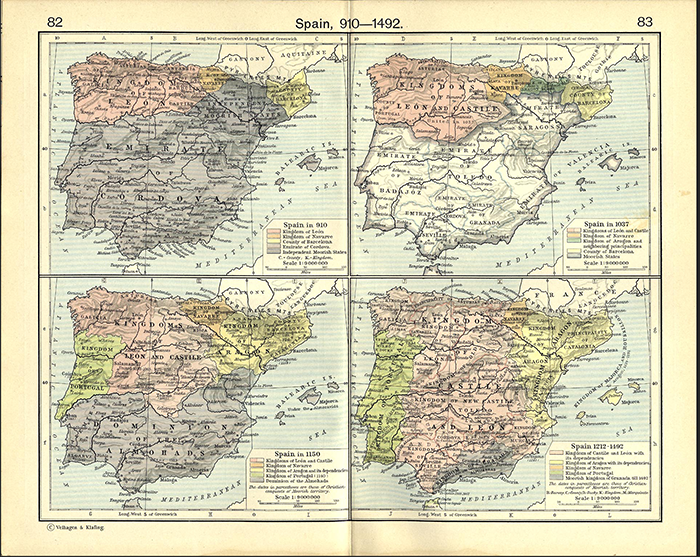

Recall that Spain had been conquered by Islamic forces starting in 711, with their northward push being halted in southern France in 732. Beginning in 750, Spain (or al-Andalus) was ruled by an offshoot of the Umayyad Dynasty from Damascus. The most famous ruler of this transplanted Umayyad Dynasty, with its capital in Cordova, was ‘Abd al-Raḥmān III , who proclaimed himself Caliph early in the tenth century, cutting off all governmental ties with Islamic governments in North Africa. He ruled for a half century, from 912 to 961, and his reign was known as “the golden age” of al-Andalus. His son, and successor, al-Ḥakam II , who reigned from 961 to 977, was, like his father, a firm supporter of the sciences who brought to Spain the best scientific works from Baghdad, Egypt, and other eastern countries. And it is from this time that we first have mathematical works written in Spain that are still extant.

Al-Ḥakam’s son, Hishām, was very young when he inherited the throne on the death of his father. He was effectively deposed by a coup led by his chamberlain, who soon instituted a reign of intellectual terror that lasted until the end of the Umayyad Caliphate in 1031. At that point, al-Andalus broke up into many small Islamic kingdoms, several of which actively encouraged the study of sciences. In fact, Sā‘id al-Andalusī, writing in 1068, noted that “The present state, thanks to Allah, the Highest, is better than what al-Andalus has experienced in the past; there is freedom for acquiring and cultivating the ancient sciences and all past restrictions have been removed” [Sā‘id, 1991, p. 62].

Figure 1. Maps of Spain in 910 (upper left), 1037 (upper right), 1150 (lower left), and 1212-1492 (lower right)

Meanwhile, of course, the Catholic “Reconquista” was well underway, with a critical date being the reconquest of Toledo in 1085. Toledo had been one of the richest of the Islamic kingdoms, but was conquered in that year by Alfonso VI of Castile. Fortunately, Alfonso was happy to leave intact the intellectual riches that had accumulated in the city, and so in the following century, Toledo became the center of the massive transfer of intellectual property undertaken by the translators of Arabic material, including previously translated Greek material, into Latin. In fact, Archbishop Raymond of Toledo strongly encouraged this effort. It was only after this translation activity took place, that Latin Christendom began to develop its own scientific and mathematical capabilities.

But what of the Jews? There was a Jewish presence in Spain from antiquity, and certainly during the time of the Umayyad Caliphate, there was a strong Jewish community living in al-Andalus. During the eleventh century, however, with the breakup of al-Andalus and the return of Catholic rule in parts of the peninsula, Jews were often forced to make choices of where to live. Some of the small Islamic kingdoms welcomed Jews, while others were not so friendly. And once the Berber dynasties of the Almoravids (1086-1145) and the Almohads (1147-1238) from North Africa took over al-Andalus, Jews were frequently forced to leave parts of Muslim Spain. On the other hand, the Catholic monarchs at the time often welcomed them, because they provided a literate and numerate class – fluent in Arabic – who could help the emerging Spanish kingdoms prosper. By the middle of the twelfth century, most Jews in Spain lived under Catholic rule. However, once the Catholic kingdoms were well-established, the Jews were often persecuted, so that in the thirteenth century, Jews started to leave Spain, often moving to Provence. There, the Popes, in residence at Avignon, protected them. By the end of the fifteenth century, the Spanish Inquisition had forced all Jews to convert or leave Spain.

Figure 2. Papal territories in Provence

It was in Provence, and later in Italy, that Jews began to fully develop their interest in science and mathematics. They also began to write in Hebrew rather than in Arabic, their intellectual language back in Muslim Spain.

Victor J. Katz (University of the District of Columbia), "The Mathematical Cultures of Medieval Europe - Introduction," Convergence (December 2017)

- Printer-friendly version

Dummy View - NOT TO BE DELETED

The Mathematical Cultures of Medieval Europe

- The Mathematical Cultures of Medieval Europe - The Mathematics of the Muslims

- The Mathematical Cultures of Medieval Europe - The Mathematics of the Jews

- The Mathematical Cultures of Medieval Europe - Mathematics in Catholic Europe

- The Mathematical Cultures of Medieval Europe - Conclusions

- The Mathematical Cultures of Medieval Europe - References

MAA Publications

- Images for Classroom Use

- MAA Reviews

- MAA History

- Policies and Procedures

- Support MAA

- Member Discount Programs

- Propose a Session

- MathFest Archive

- Putnam Competition

- AMC Resources

- Curriculum Resources

- Outreach Initiatives

- Professional Development

- Communities

Connect with MAA

Mathematical Association of America P: (800) 331-1622 F: (240) 396-5647 Email: [email protected]

Copyright © 2024

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Mobile Version

- Special Collections Home

- Archives Home

- Madrid Home

- Assessement

- Contact/Directory

- Library Associates

- Archives & Digital Services

- Databases - Article Linker FAQ

- Digital Collections

- Government Information

- Library Catalog

- Library Catalog - Alerts/Other Material

- Locating Materials in Pius Library

- Meet your Librarian

- SLU Journals and SLU Edited Journals

- SLUth Search Plus

- Special Collections

- Research Guides

- Academic Technology Commons

- Course Reserves

- Course Reserves FAQ

- Interlibrary Loan

- Journal Articles on Demand

- Library Access

- library Account

- Library Instructions

- Library Resources for Faculty and Staff

- Off Campus Library Access

- Questions? Ask Us!

- Study Space and Lockers

- Writing Program Information Literacy Instruction

- Pius Faculty and Staff

- Meet Your Pius Research Librarian

- MCL Faculty and Staff

- Meet Your MCL Liaison Librarian

Medieval and Early Modern Science and Medicine: Mathematics

- Reference Sources

- Natural Philosophy

- Astronomy/ Astrology

- Medicine and Anatomy

- Occultism and Esotericism

- Manuscripts

- Mathematics

- Science and Technology

- Transmission and Reception

- Art and science

- Websites/ Databases

Intended as an overview of available material on mathematics. Grouped into the following categories:

Medieval Mathematics

Early modern mathematics.

- "Maria Gaetana Agnesi: mathematics and the making of Catholic Enlightenment" by Massimo Mazzotti Isis 92 (2001): 657-683

- "Science and Humanism in the Renaissance: Regiomontanus's Oration of the Dignity and Utility of the Mathematical Sciences." by Noel Swerdlow Call Number: Q175.3 .W6 1993 in World Changes: Thomas Kuhn and the Nature of Science, edited by P. Horwich (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1993): 131-168.

Euclid Vatican City, Biblioteca apostolica vaticana, Cod. Vat. graec. 190, 288v-289r

- << Previous: Atomism

- Next: Transmission and Reception >>

- Last Updated: Apr 18, 2024 11:38 AM

- URL: https://libguides.slu.edu/medren_science

COMMENTS

An important (but largely unknown and underrated) mathematician and scholar of the 14th Century was the Frenchman Nicole Oresme. He used a system of rectangular coordinates centuries before his countryman René Descartes popularized the idea, as well as perhaps the first time-speed-distance graph. Also, leading from his research into musicology, he was the first to use fractional exponents ...

Early modern mathematics (roughly 1500-1700) Like all other areas of intellectual activity in the sixteenth century, mathematics was revitalized by the translation of Classical texts from Greek to Latin. It was further stimulated by the absorption of ideas from Islamic sources, and by the new technical challenges posed by increased trade and ...

Fernando Q. Gouv&ecic;a. , on. 01/10/2003. ] Essays on Early Medieval Mathematics is part of the Variorum Collected Studies series, which reproduces papers directly from their original (sometimes quite obscure) sources, preserving even the original pagination. (This is intended to make it easier to trace references to the papers, but it does ...

This work is a continuation of his previous Essays on Early Medieval Mathematics: The Latin Tradition (2003), which concentrated on European developments from the eighth to the eleventh centuries. Two of his articles in this collection appear, for the first time, in English language translation. Another two articles (chapters IV, V) remain in ...

The mathematical cultures of Medieval Europe. History and Pedagogy of Math- ematics, Jul 2016, Montpellier, France. �hal-01349229�. THE MATHEMATICAL CULTURES OF MEDIEVAL EUROPE. Victor J. KATZ. University of the District of Columbia (Emeritus) Washington, DC, USA [email protected]. ABSTRACT.

Essays on early medieval mathematics : the Latin tradition by Folkerts, Menso. Publication date 2003 Topics Mathematics, Medieval Publisher Aldershot, Hampshire, Great Britain ; Brookfield, Vt. : Ashgate/Variorum Collection printdisabled; internetarchivebooks Contributor Internet Archive

Essays on Early Medieval Mathematics. : MENSO. FOLKERTS. Taylor & Francis Group, Jun 10, 2019 - History - 382 pages. This book deals with the mathematics of the medieval West between ca. 500 and 1100, the period before the translations from Arabic and Greek had their impact. Four of the studies appear for the first time in English.

This book deals with the mathematics of the medieval West between ca. 500 and 1100, the period before the translations from Arabic and Greek had their impact. Four of the studies appear for the first time in English. Among the topics treated are: the Roman surveyors (agrimensores); recreational mathematics in the period of Bede and Alcuin ...

This book deals with the mathematics of the medieval West between ca. 500 and 1100, the period before the translations from Arabic and Greek had their impact. Four of the studies appear for the first time in English. Among the topics treated are: the Roman surveyors (agrimensores); recreational mathematics in the period of Bede and Alcuin; geometrical texts compiled in Corbie and Lorraine from ...

Essays on Early Medieval Mathematics: The Latin Tradition - by Menso Folkerts. Jens Høyrup, . Search for more papers by this author

Medieval Mathematics: Two Figures from the Later Middle Ages Teresa Kuo. The history of mathematics, like that of any science, has had periods of rapid devel-opment and growth balanced by periods of less vigorous development. In Europe, the period lasting from approximately the early 500s A.D. to the mid 1400s is collectively referred to as the ...

The Development of Mathematics in Medieval Europe complements the previous collection of articles by Menso Folkerts, Essays on Early Medieval Mathematics, and deals with the development of mathematics in Europe from the 12th century to about 1500. In the 12th century European learning was greatly transformed by translations from Arabic into Latin.

M ENSO F OLKERTS, Essays on Early Medieval Mathematics: The Latin Tradition. Variorum Collected Studies Series, CS751. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2003. Pp. 382. ISBN -86078-895-4. £59.50 (hardback). Published online by Cambridge University Press: 26 August 2005. JACKIE STEDALL. Show author details JACKIE STEDALL Affiliation:

Three years ago, I reviewed an earlier volume by Menso Folkerts in the same Variorum Collected Studies Series.Entitled Essays on Early Medieval Mathematics, it collected several of Folkerts' papers on that topic.This volume is clearly a continuation of the other, focusing this time on "The Arabs, Euclid, and Regiomontanus" (and therefore on a slightly later part of the Medieval period).

Sourcebook in the Mathematics of Medieval Europe and North Africa (Book Review) Abstract Reviewed Title: Sourcebook in the Mathematics of Medieval Europe and North Africa, by Victor J. Katz. Menso Folkerts, Barnabas Hughes, Roi Wagner, and J. Lennart Berggren, Eds., Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2016. 574 pp. ISBN: 9780691156859.

Medieval History, Medieval Studies, Medieval Mathematics, Platonism Ancient Egyptian and Greek mathematics ALCUIN, MATHEMATICS AND THE RATIONAL MIND Preamble: This is the front page of Chapter 11 in the book 'Insular Iconographies: Essays in Honour of Jane Hawkes', ed. Meg Boulton & Michael D.J. Bintley, (Boydell Press, 2019).

For most medieval scholars, who believed that God created the universe according to geometric and harmonic principles, science - particularly geometry and astronomy - was linked directly to the divine.To seek these principles, therefore, would be to seek God. European science in the Middle Ages comprised the study of nature, mathematics and natural philosophy in medieval Europe.

We begin by clarifying the words "medieval Europe", because the dates for the activities of these three cultures vary considerably. Catholic Europe, from the fall of the Western Roman Empire up until the mid-twelfth century, had very little mathematical activity, in large measure because most of the heritage of ancient Greece had been lost.

Citation styles for Essays on Early Medieval Mathematics How to cite Essays on Early Medieval Mathematics for your reference list or bibliography: select your referencing style from the list below and hit 'copy' to generate a citation. If your style isn't in the list, you can start a free trial to access over 20 additional styles from the Perlego eReader.

Essays on Early Medieval Mathematics by Menso Folkerts. Call Number: QA23 .F65 2003. The Development of Mathematics in Medieval Europe: the Arabs, ... Vestigia mathematica : studies in medieval and early modern mathematics in honour of H.L.L. Busard by M. Folkerts and J.P. Hogendijk (Editors) Call Number: QA23 .V47 1993.

The Development of Mathematics in Medieval Europe complements the previous collection of articles by Menso Folkerts, Essays on Early Medieval Mathematics, and deals with the development of mathematics in Europe from the 12th century to about 1500. In the 12th century European learning was greatly transformed by translations from Arabic into Latin. Such translations in the field of mathematics ...

The history of mathematics deals with the origin of discoveries in mathematics and the mathematical methods and notation of the past.Before the modern age and the worldwide spread of knowledge, written examples of new mathematical developments have come to light only in a few locales. From 3000 BC the Mesopotamian states of Sumer, Akkad and Assyria, followed closely by Ancient Egypt and the ...

Indian mathematics emerged in the Indian subcontinent [1] from 1200 BCE [2] until the end of the 18th century. In the classical period of Indian mathematics (400 CE to 1200 CE), important contributions were made by scholars like Aryabhata, Brahmagupta, Bhaskara II, and Varāhamihira. The decimal number system in use today [3] was first recorded ...

The Association for Women in Mathematics and Math for America have co-sponsored an essay contest calling for biographies of contemporary women in the fields of mathematics and statistics as they relate to academic, industrial and government careers; all this to raise awareness of women's ongoing contributions to the mathematical sciences.. This year Annie Katz, a ninth grader of Leffell School ...