Feminist Majority Foundation

Expanding Birth Control Access as the New Front in Reproductive Freedom

The Biden-Harris administration’s proposed rule to expand access to affordable contraception under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) is a timely and essential move, especially in the current political landscape where reproductive rights have been systematically eroded. This proposal would provide over-the-counter birth control without any cost sharing for women with private insurance, removing significant financial barriers to contraception for millions of women. This would include FDA-approved options such as Opill, the morning-after pill, and other methods like IUDs and condoms. Jennifer Klein, White House Gender Policy Council Director, emphasized that this move could have a transformative impact, ensuring more women can access contraception without cost-sharing.

This initiative couldn’t be more urgent. In the wake of the Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization —which overturned the nearly 50-year precedent set by Roe v. Wade —the landscape of reproductive healthcare has shifted dramatically. With abortion access now either severely restricted or outright banned in many states, the need for accessible birth control has become a frontline issue. Women who have lost access to safe and legal abortion options are left with limited reproductive choices, making contraception not just a health service but a critical tool of autonomy and control over one’s future. Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra emphasizes this by saying, “Now more than ever, access to and coverage of birth control is critical as the Biden-Harris administration works to help ensure women everywhere can get the contraception they need when they need it”

The proposed rule would not only strengthen access to prescribed contraceptives but also tackle the loopholes created by religious and moral exemptions that have allowed some employers and institutions to deny birth control coverage. These exemptions have been a contentious issue since 2018, when regulations allowed private health plans to exclude coverage for contraceptive services based on moral or religious objections. Under this new rule, women and dependents enrolled in plans with such exemptions will be able to access contraception directly from willing providers without additional cost, ensuring that their employer’s religious beliefs don’t determine their reproductive choices.

This policy comes at a time when contraception is more than just a personal health decision—it’s a matter of economic and social justice. Nearly 90% of women of reproductive age have used contraception at some point in their lives, and access to reliable birth control is closely tied to women’s ability to pursue higher education, maintain steady employment, and plan their families responsibly. The ability to control if and when to have children is not just a matter of health; it’s a fundamental right that impacts every facet of a woman’s life. As Alexis McGill Johnson, president and CEO of Planned Parenthood, aptly put it, “Access to birth control is critical to reproductive freedom. It gives people the reins to decide their futures.”

However, while this proposal is a positive step, it doesn’t go far enough. The fact that this expanded coverage applies only to those with private insurance leaves millions of women—especially those from low-income backgrounds—still vulnerable. Contraception should not be a luxury afforded only to those employed or enrolled in a university health plan. It should be available, free of charge, to every woman in America, regardless of income, employment status, or geography. Access to birth control shouldn’t depend on a person’s ability to navigate complex insurance systems or rely on an employer’s benevolence.

In addition, this rule still retains religious exemptions for employers, which means that women who work for religious institutions or employers who claim moral objections may still face hurdles. Although the proposal seeks to create independent pathways for these women to access contraception, the process could still impose unnecessary burdens, delaying access to timely contraceptive care . In a country that prides itself on freedom, we should be moving toward a system where reproductive health care is universal, not subject to the whims of individual employers or religious doctrine.

This proposal doesn’t address the needs of women without health insurance. While expanding access to no-cost birth control under the ACA is commendable, those without insurance remain sidelined. The U.S. should be aiming for universal access to contraception—comprehensive coverage that includes everyone, regardless of their insurance status. For a society to truly respect reproductive freedom, it must ensure that contraception is affordable and accessible to all, not just the privileged few.

The Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs has created a reproductive health crisis in the United States. As state legislatures continue to attack abortion access, the federal government must counterbalance these efforts by protecting and expanding access to contraception. The Biden-Harris administration’s proposal is a necessary first step, but it’s only that—a first step. True reproductive justice will only be achieved when contraception is universally accessible, free from bureaucratic obstacles and moralistic exclusions. Women deserve nothing less.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Biden administration proposes a rule to make over-the-counter birth control free

Chandelis Duster

In this photo illustration, a package of Opill is displayed on March 22. Justin Sullivan/Getty Images hide caption

The Biden administration is proposing a rule that would expand access to contraceptive products, including making over-the-counter birth control and condoms free for the first time for women of reproductive age who have private health insurance.

Under the proposal by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Labor Department, and Treasury Department, which was announced by the administration on Monday, health insurance companies would be required to cover all recommended over-the-counter contraception products, such as condoms, spermicide and emergency contraception, without a prescription and at no cost, according to senior administration officials.

It would also require private health insurance providers to notify recipients about the covered over-the-counter products.

The proposed rule comes as the Biden administration seeks to expand access to contraceptives and as other reproductive health, including access to abortion, has become a central issue in the 2024 presidential election campaign . Republican-led states have restricted access to abortion since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in 2022. About half of states now ban or severely restrict abortion, which has coincided with steep declines in prescriptions for birth control and emergency contraception in those states.

Birth control prescriptions are down in states with abortion bans

HHS Secretary Xavier Becerra said when health care insurers impose burdensome administrative or cost sharing requirements for services, “access to contraceptives become even more difficult.”

“We have heard from women who need a specific brand of birth control but the cost of their prescription isn’t covered by their health insurance. We have made clear that in all 50 states the Affordable Care Act guarantees coverage of women’s preventive services without cost sharing, including all birth control methods approved by the Food and Drug Administration,” Becerra told reporters. “This proposed rule will build on the progress we have already made under the Affordable Care Act to help ensure that more women can access the contraceptive services they need without out-of-pocket costs.”

The products would be able to be accessed the same way prescription medicines are accessed, such as at the pharmacy counter, according to senior administration officials. Getting the products through reimbursement would also be an option, depending on the health insurance plan, officials said.

Birth control became available to those with insurance without a copay because of the Affordable Care Act, but that required a prescription.

In July 2023, a daily oral birth control pill, Opill, became the first over-the-counter birth control pill to be approved by the Food and Drug Administration. It became available for purchase online in March and can be purchased for $19.99.

The Biden administration in January announced several actions aimed at strengthening access to abortion and contraceptives, including the Office of Personnel Management issuing guidance to insurers that will expand access to contraception for federal workers, families and retirees.

There will be a comment period on the proposed rule and if approved, it could go into effect in 2025, according to senior administration officials.

However, if former President Donald Trump wins the election, he could reverse the rule.

NPR’s Sydney Lupkin and Bill Chappell contributed to this report.

- Birth Control

- Health Care

Amanda Seitz, Associated Press Amanda Seitz, Associated Press

Leave your feedback

- Copy URL https://www.pbs.org/newshour/health/health-insurance-needs-to-fully-cover-over-the-counter-birth-control-like-condoms-white-house-says

Health insurance needs to fully cover over-the-counter birth control like condoms, White House says

WASHINGTON (AP) — Millions of people with private health insurance would be able to pick up over-the-counter methods like condoms, the “morning after” pill and birth control pills for free under a new rule the White House proposed on Monday.

Right now, health insurers must cover the cost of prescribed contraception, including prescription birth control or even condoms that doctors have issued a prescription for. But the new rule would expand that coverage, allowing millions of people on private health insurance to pick up free condoms, birth control pills, or “morning after” pills from local storefronts without a prescription.

The proposal comes days before Election Day, as Vice President Kamala Harris affixes her presidential campaign to a promise of expanding women’s health care access in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to undo nationwide abortion rights two years ago. Harris has sought to craft a distinct contrast from her Republican challenger, Donald Trump, who appointed some of the judges who issued that ruling.

READ MORE: Abortion passes inflation as top election concern for women under 30, survey finds

“The proposed rule we announce today would expand access to birth control at no additional cost for millions of consumers,” Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra said in a statement. “Bottom line: women should have control over their personal health care decisions. And issuers and providers have an obligation to comply with the law.”

The emergency contraceptives that people on private insurance would be able to access without costs include levonorgestrel, a pill that needs to be taken immediately after sex to prevent pregnancy and is more commonly known by the brand name “Plan B.”

Without a doctor’s prescription, women may pay as much as $50 for a pack of the pills. And women who delay buying the medication in order to get a doctor’s prescription could jeopardize the pill’s effectiveness, since it is most likely to prevent a pregnancy within 72 hours after sex.

WATCH: Over-the-counter birth control pill approved for sale in U.S.

If implemented, the new rule would also require insurers to fully bear the cost of the once-a-day Opill, a new over-the-counter birth control pill that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved last year. A one-month supply of the pills costs $20.

Federal mandates for private health insurance to cover contraceptive care were first introduced with the Affordable Care Act, which required plans to pick up the cost of FDA-approved birth control that had been prescribed by a doctor as a preventative service.

The proposed rule would not impact those on Medicaid, the insurance program for the poorest Americans. States are largely left to design their own rules around Medicaid coverage for contraception, and few cover over-the-counter methods like Plan B or condoms.

Support Provided By: Learn more

Educate your inbox

Subscribe to Here’s the Deal, our politics newsletter for analysis you won’t find anywhere else.

Thank you. Please check your inbox to confirm.

The Washington Post’s essential guide to health policy news

Ahead of election, White House proposes free over-the-counter birth control

Good morning! We’re just over two weeks until Election Day. But it’s still October, a month where back in 1980 a Ronald Reagan campaign operative coined the term “October surprise.” Got tips? Send ‘em on over to your guest host at [email protected] .

Today’s edition: Two federal agencies are collaborating to advance efforts to develop new products that help people quit smoking. How a new parental consent law in Idaho is affecting care for young people. But first …

Could birth control be free without a prescription?

In July 2023, the Food and Drug Administration approved the first over-the-counter birth control pill in the United States. But there was a catch: The medication was not free for most people.

The White House is now proposing to broaden access to free birth control covered by private health insurance plans — a bid that surfaces one of Democrats’ most potent issues just over two weeks before Election Day, my colleague Carolyn Y. Johnson and I report. The administration is unveiling a proposed rule today that would mandate private health plans cover over-the-counter birth control — including daily pills, emergency contraceptives and condoms — without a prescription and at no cost.

Democrats are focusing on reproductive health ahead of the election after abortion rights measures have had a winning streak at the ballot box.

Vice President Kamala Harris has made reproductive rights a centerpiece of her campaign for the White House, and Democrats are banking on the issue to help the party not only defeat former president Donald Trump but also maintain control of the Senate and recapture the House. This November marks the first presidential election since the Supreme Court overturned the constitutional right to an abortion in June 2022, fueling a seismic shift in the nation’s reproductive health landscape.

Reproductive health advocates have said making contraception easily available is more important than ever in a post- Roe world where most abortions are banned in more than a dozen states. Prominent Democrats and reproductive rights advocates have urged the Biden administration to make over-the-counter birth control free.

The details

The Affordable Care Act mandates that insurance companies cover contraception at no cost. But plans are not required to cover items available over the counter unless the patient has a prescription.

The rule seeks to change that, with Biden administration officials projecting that roughly 52 million women of reproductive age who are covered by private health plans would be able to get free birth control over the counter.

One key question: How would such a proposal work in practice?

Health plans could choose different ways to administer the plan, officials said, while adding that more details could come in a final rule. Some consumers may be able to get free birth control by picking it up in a store aisle and bringing it to the pharmacy counter. Officials didn’t rule out the possibility of consumers buying products and then seeking reimbursement from their health plans.

The White House would also seek to expand the choice of birth control — currently, insurers are required to cover only one drug within each category of contraception. Under the proposal, insurers would have to cover all approved drugs, unless they have a therapeutic equivalent that is covered. The end result would be more brands of birth control pills and a wider selection of IUDs available for free.

But will the administration actually finalize the rule? It will be a tough lift because the plan must undergo a 60-day comment period, and it often takes months to years for federal agencies to respond to comments and release a final plan. But a key administration official insists finalizing the rule in the coming months is possible.

“We will work quickly to conclude it before the end of this administration,” Jennifer Klein, the director of the White House Gender Policy Council, said in an interview. “The urgency is clear.”

Read our full story here.

Agency alert

FDA, NIH push for innovation in smoking cessation therapies

On tap today: The Food and Drug Administration and the National Institutes of Health are teaming up for a joint public meeting to discuss potential new tools to help adults and youths stop smoking.

In an op-ed last week , senior officials from both agencies emphasized the “urgent need” for innovation in smoking cessation treatments, calling it a “high-priority area” for the federal government. Notably, they suggested that reductions in smoking should be considered a meaningful endpoint in clinical trials for new products, a departure from their traditional emphasis on complete abstinence.

The authors also called for more research on e-cigarettes, including long-term health outcomes and whether the devices could eventually be marketed as therapeutic tools, rather than just tobacco products.

In other news from the agencies …

Lykos Therapeutics sees a “path forward” for its MDMA-assisted treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder after federal regulators declined to approve it over the summer.

In a statement Friday, the company announced that its new interim CEO, Michael Mullette , and chief medical officer, David Hough , had a “productive meeting” with the FDA about next steps for the first-of-its-kind treatment. Next steps include an additional Phase 3 trial, and a potential independent third-party review of prior clinical trial data.

Key context: In August, the FDA rejected Lykos’s current application , citing “significant limitations” in its data that the agency said prevented it from determining whether the treatment was safe and effective. The federal regulator called for another large study — a request the company has pushed back on, arguing that the existing data is adequate to prove the drug’s efficacy.

Idaho’s new parental consent law for health care draws sharp criticism

The Post’s Karin Brulliard is out this morning with a deep dive into Idaho’s new law requiring parental consent for nearly all health care that a minor receives.

Supporters of the law, which allows for emergency treatment, say it’s a reasonable step to prevent adolescents from discussing issues such as birth control and gender identity with doctors, counselors and other adults unless their parents are informed first.

But critics argue it ignores the reality that not all parents are present or trustworthy and removes essential confidentiality protections by granting parents access to minors’ health records. Three months after the law’s implementation, they say it’s limiting adolescents’ access to counseling, complicating evidence collection in sexual assault cases and forcing schools to seek parental permission to treat scrapes with ice packs and Band-Aids.

- “It has been a terrible bill with terrible outcomes,” said state Rep. Marco Erickson (R), a youth organization director who voted for the measure despite misgivings. “I have seen youth not want to participate in therapy for fear their abuser would gain access to what they are talking about.”

The bigger picture: The law is part of a broader parental rights movement. It was supported by the Alliance Defending Freedom , a conservative Christian group that has notched several U.S. Supreme Court victories and points to gender-affirming school counseling as an example of youth health care gone awry. The group says seven states, including Idaho, now “fully” protect parental rights in health-care decisions.

Industry Rx

FLOTUS, top health officials hit Las Vegas for HLTH 2024

On our radar: Thousands of health-care providers, industry leaders and advocates are converging on Las Vegas this week for HLTH 2024 , a major conference featuring top government officials and even a few celebrities.

The event, which kicked off Sunday at the Venetian Expo Center , runs through Wednesday. Here’s what we’re keeping an eye on:

On tap today: FDA Commissioner Robert Califf will discuss health-care innovation, regulation and patient safety. Later, Chelsea Clinton and White House Gender Policy Council Director Jennifer Klein will talk about reproductive rights and the challenges surrounding abortion access.

On Tuesday: Rep. Morgan Luttrell (R-Tex.), Sen. Kyrsten Sinema (I-Ariz.), and Shereef Elnahal , undersecretary for health at the Department of Veterans Affairs , will explore the future of psychedelic medicines and their potential for mental health therapy.

On Wednesday: first lady Jill Biden will spotlight the White House’s efforts to advance women’s health research. Her remarks will be followed by a discussion on the topic featuring Renee Wegrzyn , director of the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health , and Carolyn Mazure , chair of the White House Initiative on Women’s Health Research, among others.

In other health news

- On the move: CVS Health has named David Joyner its president and CEO, replacing Karen Lynch . Joyner, who previously served as executive vice president of CVS Health and president of CVS Caremark , also joined the company’s board of directors.

- The first shipments of intravenous fluids from Baxter International’s overseas facilities arrived in the United States over the weekend, the federal health department announced , adding that hospitals now have 50 percent more product available than they did immediately after Hurricane Helene.

- Humana Inc. sued the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, seeking a federal court’s reversal of the agency’s decision to cut the rating of one of its most popular Medicare Advantage plans, John Tozzi reports for Bloomberg News .

Health reads

Harris goes after Trump on abortion rights during Georgia rally (By Brianna Tucker, Maegan Vazquez and Dylan Wells | The Washington Post)

Amid backlash, FDA changes course over shortage of weight-loss drugs (By Daniel Gilbert | The Washington Post)

The Powerful Companies Driving Local Drugstores Out of Business (By Reed Abelson and Rebecca Robbins | The New York Times)

View this post on Instagram A post shared by Dabin Han (@dabiliciouss)

Thanks for reading! Not a subscriber? Sign up here.

We've detected unusual activity from your computer network

To continue, please click the box below to let us know you're not a robot.

Why did this happen?

Please make sure your browser supports JavaScript and cookies and that you are not blocking them from loading. For more information you can review our Terms of Service and Cookie Policy .

For inquiries related to this message please contact our support team and provide the reference ID below.

LAist is part of Southern California Public Radio, a member-supported public media network.

Biden administration proposes a rule to make over-the-counter birth control free

The Biden administration is proposing a rule that would expand access to contraceptive products, including making over-the-counter birth control and condoms free for the first time for women of reproductive age who have private health insurance.

Under the proposal by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Labor Department, and Treasury Department, which was announced by the administration on Monday, health insurance companies would be required to cover all recommended over-the-counter contraception products, such as condoms, spermicide and emergency contraception, without a prescription and at no cost, according to senior administration officials.

It would also require private health insurance providers to notify recipients about the covered over-the-counter products.

The proposed rule comes as the Biden administration seeks to expand access to contraceptives and other reproductive health, including access to abortion, has become a central issue in the 2024 presidential election campaign . Republican-led states have restricted access to abortion since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in 2022. About half of states now ban or severely restrict abortion, which has coincided with steep declines in prescriptions for birth control and emergency contraception in those states.

HHS Secretary Xavier Becerra said when health care insurers impose burdensome administrative or cost sharing requirements for services, “access to contraceptives become even more difficult.”

“We have heard from women who need a specific brand of birth control but the cost of their prescription isn’t covered by their health insurance. We have made clear that in all 50 states the Affordable Care Act guarantees coverage of women’s preventive services without cost sharing, including all birth control methods approved by the Food and Drug Administration,” Becerra told reporters. “This proposed rule will build on the progress we have already made under the Affordable Care Act to help ensure that more women can access the contraceptive services they need without out-of-pocket costs.”

The products would be able to be accessed the same way prescription medicines are accessed, such as at the pharmacy counter, according to senior administration officials. Getting the products through reimbursement would also be an option, depending on the health insurance plan, officials said.

Birth control became available to those with insurance without a copay because of the Affordable Care Act, but that required a prescription.

In July 2023, a daily oral birth control pill, Opill, became the first over-the-counter birth control pill to be approved by the Food and Drug Administration. It became available for purchase online in March and can be purchased for $19.99.

The Biden administration in January announced several actions aimed at strengthening access to abortion and contraceptives, including the Office of Personnel Management issuing guidance to insurers that will expand access to contraception for federal workers, families and retirees.

There will be a comment period on the proposed rule and if approved, it could go into effect in 2025, according to senior administration officials.

However, if former President Donald Trump wins the election, he could reverse the rule.

NPR’s Sydney Lupkin and Bill Chappell contributed to this report. Copyright 2024 NPR

Abortion rights, women of color, and LGBTQIA+ people are under attack. Pledge to join us in fighting for gender justice.

By submitting your cell phone number you are agreeing to receive periodic text messages from this organization. Message and data rates may apply. Text HELP for more information. Text STOP to stop receiving messages.

Over the past year, the National Women’s Law Center has achieved historic victories for women and families—even while facing one of the biggest crisis moments in our country’s history. Join us at our annual gala to celebrate and hear from changemakers across sectors who are fighting to build a country that is equitable for all women, girls, and those across the gender spectrum.

- Equal Pay & the Wage Gap

- General Health Care & Coverage

- Poverty & Income Security

- Supreme Court

- Child Care & Early Learning Access & Affordability

- Child Care & Early Learning Policy Implementation

- Child Care & Early Learning Workforce

- Sexual Harassment in Schools

- School Discipline & Pushout Prevention

- Pregnant & Parenting Students

- Birth Control

- Refusals of Care & Discrimination

- In the States

- Judicial Nominations

- LGBTQ Equality

- Income Supports

- Data On Poverty & Income

- Job Quality

- Equal Pay & the Wage Gap

- Sexual Harassment in the Workplace

- Pregnancy, Parenting & the Workplace

- How We Work

- NWLC's Founders

- Board of Directors

- Jobs at NWLC

- Legal Help for Sex Discrimination and Harassment

- Legal Help for Abortion Patients and Supporters

- Abortion Provider Legal Help

- Birth Control & Preventive Services Coverage

- Press Releases

- NWLC In The Press

- Take Action

- Partner With Us

- Attend the 2024 Gala

- Share Your Story

- Find Resources

- Supporter Shop

- Become a Monthly Changemaker

- Ways to Give

- Partner with Us

- Support Our Gala

press release

Nwlc applauds the biden administration for proposing broader access to free birth control.

October 21, 2024 – Today, the Biden Administration announced plans to expand access to no-cost birth control by ensuring coverage of over-the-counter contraceptives without cost-sharing, making sure insurance plans provide coverage without cost-sharing for the particular method an individual needs, and making it easier for individuals to learn about their contraceptive coverage.

In response, Fatima Goss Graves, president and CEO of the National Women’s Law Center, issued the following statement:

“Everyone deserves the freedom to make decisions about their bodies and futures. That includes being able to access the birth control they want or need, without any barriers in their way. We applaud the Biden Administration’s proposed rule building on the historic gains of the Affordable Care Act, which first guaranteed birth control coverage without out-of-pocket costs for millions. This new proposed rulemaking expands birth control coverage in critical ways and helps to end insurance company practices that denied people–including our many CoverHer clients–the coverage they are entitled to by law.”

“This new effort is especially critical as we confront rising threats from anti-abortion, anti-reproductive health extremists, such as those behind the Project 2025 agenda, which seek to undo important gains we’ve made, including for contraceptive coverage. In the face of these threats, the Biden Administration’s action will help remove barriers and ensure that people can get the birth control they need, when they need it. NWLC is ready to work with the Biden administration and other stakeholders to make sure that this leads to meaningful change for people across the country.”

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Should oral contraceptive pills be available without a prescription? A systematic review of over-the-counter and pharmacy access availability

Caitlin e kennedy, ping teresa yeh, lianne gonsalves, hussain jafri, mary eluned gaffield, james kiarie, manjulaa l narasimhan.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Correspondence to Dr Manjulaa L Narasimhan; [email protected]

Corresponding author.

Received 2019 Jan 8; Revised 2019 Jun 7; Accepted 2019 Jun 8; Collection date 2019.

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

Introduction

Making oral contraceptives (OC) available over the counter (OTC) could reduce barriers to use. To inform WHO guidelines on self-care interventions, we conducted a systematic review of OTC availability of OCs.

We reviewed data on both effectiveness and values and preferences surrounding OTC availability of OCs. For the effectiveness review, peer-reviewed articles were included if they compared either full OTC availability or pharmacist-prescribing (behind-the-counter availability) to prescription-only availability of OCs and measured an outcome of interest. For the values and preferences review, we included peer-reviewed articles that presented primary data (qualitative or quantitative) examining people’s preferences regarding OTC access to OCs. We searched PubMed, CINAHL, LILACS and EMBASE through November 2018 and extracted data in duplicate.

The effectiveness review included four studies with 5197 total participants. Two studies from the 2000s compared women who obtained OCs OTC in Mexico to women who obtained OCs from providers in either Mexico or the USA. OTC users had higher OC continuation rates over 9 months of follow-up (adjusted HR: 1.58, 95 % CI 1.11 to 2.26). One study found OTC users were more likely to report at least one WHO category 3 contraindication (13.4% vs 8.6%, p=0.006), but not category 4 contraindications; the other study found no differences in contraindicated use. One study found lower side effects among OTC users and high patient satisfaction with both OTC and prescription access. Two cross-sectional studies from the 1970s in Colombia and Mexico found no major differences in OC continuation, but some indication of slightly higher side effects with OTC access. In 23 values and preference studies, women generally favoured OTC availability. Providers showed more modest support, with pharmacists expressing greater support than physicians. Support was generally higher for progestogen-only pills compared with combination OCs.

A small evidence base suggests women who obtain OCs OTC may have higher continuation rates and limited contraindicated use. Patients and providers generally support OTC availability. OTC availability may increase access to this effective contraceptive option and reduce unintended pregnancies.

Systematic review (PROSPERO) registration number

CRD42019119406.

Keywords: systematic review, oral contraceptives, over-the-counter, pharmacy access

Key questions.

What is already known.

Making oral contraceptives (OC) available over the counter (OTC) may increase access.

What are the new findings?

A systematic review of the literature identified four studies using comparative designs to examine the effect of OTC availability of OCs and 23 studies examining values and preferences of patients and providers, mostly from the USA and Mexico.

The more recent and rigorous studies suggested OTC users had higher rates of OC continuation over time; there was some indication that OTC users had lower rates of side effects but slightly higher rates of use of OCs despite contraindications.

Values and preferences suggested general support for OTC availability or pharmacy access, with more support among women and pharmacists than among physicians.

What do the new findings imply?

Making OCs available OTC, perhaps with progestogen-only pills that have fewer contraindications to use, may be an approach to increasing access to and use of this effective contraceptive option.

Ensuring access to contraceptive methods, including for vulnerable populations and young people, is essential for the well-being and autonomy of women and girls. Oral contraceptives (OC), both combined oral contraceptives (COC) and progestogen-only pills (POP), are widely used effective methods of birth control. However, access to OCs varies globally—in some countries, OCs are available over the counter (OTC), while other countries restrict access to OCs either by requiring eligibility screening by trained pharmacy staff before dispensation (pharmacy access, or behind-the-counter availability), or by requiring a healthcare provider’s prescription. A 2015 review of OC access across 147 countries found that 35 countries had OCs legally available OTC, 11 countries had OCs available without a prescription but only after eligibility screening by trained pharmacy staff, 56 countries had OCs available informally without a prescription and 45 countries required a prescription to obtain OCs. 1 Given the persistently high proportion of unintended pregnancies globally—44% according to some estimates 2 —making OCs available OTC in more settings has the potential to reduce barriers to access, thereby increasing use of this effective contraceptive option and reducing unintended pregnancies.

While different regulatory criteria are needed in different countries to make a specific medication available OTC or with eligibility screening by pharmacy staff, the WHO is responsible to provide overall guidance to critical questions of whether interventions should be recommended or not. We conducted this systematic review in the context of developing WHO normative guidance on self-care interventions for sexual and reproductive health and rights. We included both a review of effectiveness data and a review of data on values and preferences.

Effectiveness review: PICO question and inclusion criteria

We sought to answer the following question: should contraceptive pill/oral contraceptives be made available over the counter without a prescription?

Our effectiveness review followed the PICO question format:

Individuals using contraceptive pill/oral contraceptives.

Intervention

Availability of contraceptive pill/oral contraceptives OTC (without a prescription) or behind the counter (pharmacy access, including dispensing from trained pharmacy personnel and pharmacist prescribing of hormonal birth control).

Availability of contraceptive pill/oral contraceptives by prescription only.

Uptake of OCs (initial use).

Continuation of OCs (or, conversely, discontinuation).

Adherence to OCs (correct use).

Comprehension of instructions (product label).

Health impacts (unintended pregnancy, side effects, adverse events or use of OCs despite contraindications).

Social harms (eg, coercion, violence (including intimate partner violence, violence from family members or community members, and so on), psychosocial harm, self-harm, and so on), and whether these harms were corrected/had redress available.

Client satisfaction.

To be included in the effectiveness review, a study had to meet the following criteria:

Employ a study design comparing OTC availability of OCs (with or without pharmacist dispensation) to prescription-only availability of OCs.

Measured one or more of the outcomes listed above.

Published in a peer-reviewed journal.

We focused on daily contraceptive pill/oral contraceptives for routine pregnancy prevention and did not include studies examining pills specifically for emergency contraception.

Where data were available, we stratified all analyses by the following subcategories:

Behind-the-counter (pharmacy access) versus OTC availability without a prescription.

COCs versus POPs.

Point of access (eg, stores, pharmacies, and so on).

Prior use of contraception.

Age: adolescent girls and young women (aged 10–14, 15–19 and 15–24) and adult women (aged 25+).

Vulnerabilities (ie, poverty, disability, religion).

High-income versus low/middle-income countries.

Literacy/educational level.

Study inclusion was not restricted by location of the intervention or language of the article. We planned to translate articles in languages other than English if identified. The complete protocol was registered and is available in PROSPERO (CRD42019119406).

Values and preferences review: inclusion criteria

The same search strategy was used to search and screen for study inclusion in a complementary review of values and preferences related to OTC access to OCs (including pharmacy access). We included studies in the values and preferences review if they presented primary data (qualitative or quantitative) examining people’s preferences regarding OTC access to OCs. We included studies examining the values and preferences of both people who have used or potentially would use OCs themselves as well as providers (including pharmacists) and other stakeholders, such as male partners, policymakers and insurance providers.

Search strategy

The same search strategy was used for both the effectiveness review and the values and preferences review. We searched four electronic databases (PubMed, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILACS) and Embase) through the search date of 30 November 2018. The following search strategy was developed for PubMed and adapted for entry into all computer databases; a full list of search terms for all databases is available from the authors on request.

(‘Contraceptives, Oral’ [Mesh] OR ‘oral contraceptive pill’ [tiab] OR ‘oral contraceptive pills’ [tiab] OR ‘birth control pill’ [tiab] OR ‘birth control pills’ [tiab] OR ‘oral contraceptives’ [tiab] OR ‘oral contraception’ [tiab] OR ‘hormonal birth control’ [tiab] OR ‘hormonal contraception’ [tiab] OR ‘the pill’ [tiab]) AND (‘Nonprescription Drugs’ [Mesh] OR ‘nonprescription’ [tiab] OR ‘over the counter’ [tiab] OR ‘over-the-counter’ [tiab] OR ‘without a prescription’ [tiab] OR ‘pharmacist-prescribed’ [tiab] OR ‘pharmacy access’ [tiab] OR ‘clinician-prescribed’ [tiab] OR ‘physician-prescribed’ [tiab] OR ‘without prescription’ [tiab] OR ‘community pharmacy services’ [Mesh] OR ‘community center’ [tiab] OR ‘community centre’ [tiab] OR store [tiab] OR online [tiab] OR mobile [tiab] OR telehealth [tiab])

To identify articles that may have been missed through online database searching, we used several complementary approaches. We reviewed the resources section of the OCs OTC working group website, 3 which gathers scientific articles and reviews on this topic, and reviewed the citations included in several related recent reviews. 1 4 5 Secondary reference searching was also conducted on all studies included in the review. We searched for ongoing trials through ClinicalTrials.gov, the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, the Pan African Clinical Trials Registry, and the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry. Finally, selected experts in the field were presented with our list of included articles and asked to share any additional article we had missed.

Titles, abstracts, citation information and descriptor terms of citations identified through the search strategy were initially screened by a member of the study staff. Remaining citations were then screened in duplicate by two reviewers (CEK and PTY) with differences resolved through consensus. Final inclusion was determined after full-text review.

Data extraction and analysis

For each included article, data were extracted independently by two reviewers using standardised data extraction forms. Differences in data extraction were resolved through consensus.

For the effectiveness review, data extraction forms covered the following categories:

Study identification: author(s); type of citation; year of publication, funding source.

Study description: study objectives; location; population characteristics; type of oral contraceptives; description of OTC access; description of any additional intervention components (eg, any education, training, support provided); study design; sample size; follow-up periods and loss to follow-up.

Outcomes: analytical approach; outcome measures; comparison groups; effect sizes; CIs; significance levels; conclusions; limitations.

Risk of bias: assessed for randomised controlled trials with the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias, 6 and for non-randomised trials but comparative studies with the Evidence Project risk of bias tool. 7

For the values and preferences review, data extraction forms included sections on study location, population, study design and key findings.

We did not conduct meta-analysis due to the small number and heterogeneous nature of included studies. Instead, we report findings based on the coding categories and outcomes.

Patient and public involvement

Several of the authors are current or past OC users. HJ, chair of the advisory group for the WHO Patients for Patients Safety Program, was involved as a community representative starting with the phase of protocol development. He commented on the overall study design and protocol, including patient-relevant outcomes, interpretation of results and writing/editing the document for readability and accuracy. Patients were involved in a global survey of values and preferences and in focus group discussions with vulnerable communities conducted to inform the WHO guideline on self-care interventions 8 ; they thus play a significant role in the overall recommendation informed by this review.

Search results

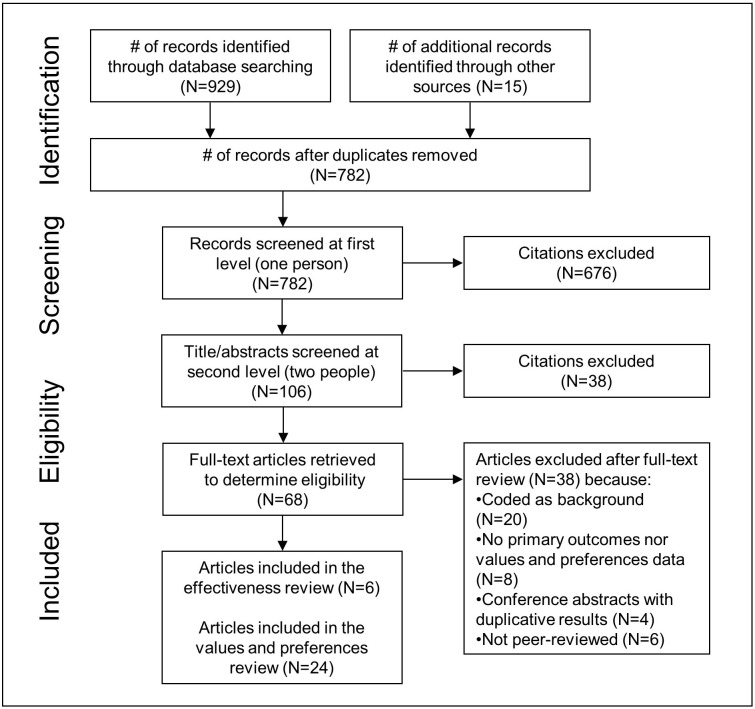

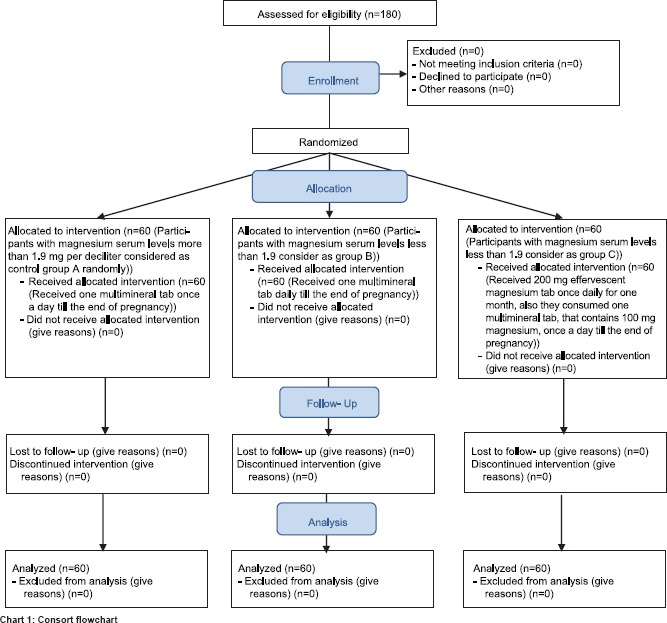

Figure 1 presents a flow chart showing study selection for both the effectiveness and values and preferences reviews. The initial database search yielded 929 records, with 15 records identified through other sources; 782 remained after removing duplicates. After the initial title/abstract review, 68 articles were retained for full-text screening. Ultimately, six articles reporting data from four studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the effectiveness review. 9–14 An additional 24 articles from 23 studies were included in the values and preferences review. 13 15–37

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart showing disposition of citations through the search and screening process.

One study was considered for the effectiveness review but ultimately judged to not meet the inclusion criteria. 38 In Kuwait, where OCs are available OTC, the study compared women who consulted with a physician and those who did not. We excluded the study because it was not clear whether women received OCs from these physicians or not. However, we note that the study found no difference across groups in OC continuation, duration of first OC use, method failure and reasons for discontinuation.

Effectiveness review

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the four studies included in the effectiveness review. 9–14 The first study, the Border Contraceptive Access Study, was a longitudinal cohort study conducted among women living in El Paso, Texas, USA, from 2006 to 2008 with results reported in a number of articles. 10 12 13 The study used convenience sampling to enrol 1046°C users who obtained OCs either OTC from a Mexican pharmacy (n=532) or from a family planning clinic in El Paso (n=514). These women were interviewed at baseline and then followed in three additional surveys over 9 months. The second study, an analysis of data from the 2000 Mexican National Health Survey 14 by an overlapping group of researchers, was a cross-sectional comparison of women who reported obtaining OCs OTC to women who reported obtaining them from a healthcare provider. The third and fourth studies were significantly older, drawing on data from the 1970s. They presented cross-sectional comparisons of women whose initial contraceptive method was OCs, obtained OTC from a pharmacy/drugstore, from a private provider/clinician or the national family planning programme: one analysed data from the 1979 Mexico National Fertility and Mortality Study among 2063 women 9 and the other was a 1974 Fertility and Contraceptive Use survey in Bogotá, Colombia, among 893 women. 11 All studies included mainly women using COCs, rather than POPs, although pill formulations likely differed by time.

Descriptions of studies included in the effectiveness review

OC, oral contraceptive; OTC, over the counter.

As all studies were observational, table 2 shows the risk of bias assessments using the Evidence Project tool. The Border Contraceptive Access and Mexican National Health Survey studies found that women who obtained their OCs OTC were different in at least some sociodemographic characteristics than those who obtained them from clinics; however, both studies employed analyses that adjusted for confounders to address this discrepancy. 10 12–14 The Mexico National Fertility and Mortality Study and Colombian Fertility and Contraceptive Use Survey said there were only minor sociodemographic differences between groups but did not present actual statistics to support these statements; neither study adjusted for confounders. 9 11 The Border Contraceptive Access Study relied on convenience sampling, but was strengthened by its longitudinal design. 10 12 13 Conversely, while the other three studies were cross sectional in nature, they were strengthened by their multistage sampling strategies. 9 11 14

Evidence Project risk of bias assessment 7 for studies included in the effectiveness review

*Four-stage probability proportionate to size sampling.

†Authors state that the comparison groups were similar, but no comparative data provided to assess this.

‡Three-stage probability sampling.

N/A, not applicable; NR, not reported.

The included studies reported on three of the PICO outcomes: continuation of OCs, health impacts (specifically, use of OCs despite contraindications and side effects) and client satisfaction. For the other PICO outcomes, we found no studies. Results from each study are presented in table 3 and described below.

Outcomes of studies included in the effectiveness review

OC, oral contraceptive;OTC, over the counter.

Continuation of OCs

The Border Contraceptive Access Study reported the proportion of women who continued OC use over the 9-month study period. 12 Overall, 25.1% of clinic users discontinued by the end of the study period compared with 20.8% of OTC users (p=0.12). In an unadjusted Cox proportional hazards model, OTC users were more likely to continue OC use than clinic users (unadjusted HR: 1.48, 95% CI 1.07 to 2.04); this estimate changed only slightly in the adjusted model and remained statistically significant (adjusted HR: 1.58, 95% CI 1.11 to 2.26).

The two studies from the 1970s also examined continuation. The Mexico National Fertility and Mortality Study presented continuation rates at 12 months per 100 women who accepted OCs as their first contraceptive method. 9 No difference by OC source was found: 59% of private physician or clinic users, 57% of government family planning programme users and 60% of OTC users remained on OCs after 12 months. The Colombian Fertility and Contraceptive Use Survey presented first contraceptive method continuation rates for women who chose OCs at 12 and 24 months. 11 Though a validation survey found that the continuation rates were overestimated by approximately 10%–15%, the study found that at both 12 and 24 months, OC continuation was approximately 5% higher for clinic users than OTC users.

Use of OCs despite contraindications

The two studies from the 2000s reported on the use of OCs despite contraindications.

The Border Contraceptive Access Study reported use of OCs despite contraindications using the WHO Medical Eligibility Criteria (MEC) (third edition) relative (category 3) and absolute (category 4) contraindications. 10 At the baseline survey, at least one category 3 or 4 contraindication was reported by 21.4% of OTC users and 13.8% of clinic users (p=0.002). OTC users were more likely to have any category 3 contraindication (13.4% vs 8.6%, p=0.006), but there was no difference in category 4 contraindications (7.4% vs 5.3%, p=0.162). The study also provided a list of specific contraindications. For most contraindications there was no significant difference for OTC and clinic users; however, OTC users were significantly more likely than clinic users to have category 3 hypertension (140–159/90–99) (8.4% vs 4.5%, p=0.036) or to both smoke (<15 cigarettes per day) and be 35 years or older (6.4% vs 3.1%, p=0.017).

The 2000 Mexican National Health Survey analysis reported use of OCs despite category 3 contraindications using the WHO MEC Criteria from 1996 based on hypertension and smoking at or over age 35. 14 Overall, the study found no significant differences in contraindications between OC users who obtained their pills OTC versus those who obtained them at a clinic ( table 3 ). This finding held true when comparing OTC to clinic users on contraindications related to hypertension (≥160/100) (1.7% vs 1.8%), smoking and age 35 or older (9.4% vs 7.5%), and both contraindications combined (4.5% vs 3.6%).

Side effects

Two studies reported on side effects related to OC use. The Border Contraceptive Access Study found that, at baseline, 22.3% (104/466) of OTC users reported side effects compared with 30.4% (144/474) of clinic users (p<0.01). 12 The Colombian Fertility and Contraceptive Use Survey found that 51% of OTC users and 44.4% of clinic users reported any side effect from initial OC use. 11 Neither group reported the most important complications of OC use (thrombophlebitis and thromboembolism), and similar proportions reported the most common side effect (headache). OTC users were more likely to mention nervousness, skin problems, pain and bleeding problems, while clinic users were more likely to complain of weight changes, varices and other side effects (not specified).

Satisfaction

One study—the Border Contraceptive Access Study—reported client satisfaction but did not present exact results. They stated, ‘three quarters of clinic users and more than 70% of pharmacy users said they were very satisfied with their source (results not shown). Only about 4% of each group said they were either somewhat or very unsatisfied with their source.’ 13

Values and preferences review

We identified 24 articles from 23 studies that met the inclusion criteria for the values and preferences review. Of these, 13 articles focused on the perspectives of female OC users, potential users, or women in general, 13 15 16 18 19 21–24 29–31 37 9 focused on the perspectives of healthcare providers (particularly physicians) and pharmacists 17 25 26 28 32–36 38 , 39 and 1 focused on the general public; 27 one article included both women and healthcare providers. 20 Almost all studies were conducted in the USA, except for one each in Canada, 32 France 17 and Ireland 15 ; one publication from the Border Contraceptive Access Study included in the values and preferences review included women residing in El Paso, Texas, who accessed OCs in both the USA and Mexico. 13 Studies used both quantitative and qualitative methodologies.

Studies covered both OTC and pharmacy access. While most studies of women asked about hypothetical values and preferences around OTC availability, a few studies reported the perspectives of women who had actually used OTC or pharmacy access services. 13 20 Most studies distinguished between pharmacy access and OTC availability, although a few were less clear about which approach they were studying, using terms such as ‘access to oral contraceptives without a prescription,’ which we assumed to be OTC availability. Using our best assessment of which model studies were examining, we present data for the values and preferences studies separated by true OTC access ( table 4 ) and pharmacy access ( table 5 ), and present results accordingly below. Two studies examined perspectives on both OTC and pharmacy access, so are presented in both tables 4 and 5 . One cross-sectional survey among young women aged 14–17 in the USA found slightly higher support for dispensation in pharmacies compared with full OTC availability (79% vs 73%), but slightly higher potential use of full OTC availability compared with pharmacy access (61% vs 57%). 30 Another cross-sectional survey among healthcare providers in the USA found much higher rates of support for pharmacy access (74%) compared with full OTC access (28%), although this study combined the pill, patch and ring together in one question about hormonal contraceptives. 35

Study descriptions and key findings of studies included in the values and preferences review examining OTC access

OC, oral contraceptive; OCP, Oral Contraceptive Pill; OTC, over the counter;POP, progestogen-only pill; STI, sexually transmitted infection; aOR, adjusted OR.

Study descriptions and key findings of studies included in the values and preferences review examining pharmacy access

OC, oral contraceptive;OTC, over the counter;STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Across studies using both quantitative and qualitative methods, women generally expressed high interest in hypothetical OTC availability of OCs. In quantitative studies, support for OTC availability of OCs ranged from a third of female students in two US colleges/universities 19 31 to 89% of current OC users aged 18–50 in Ireland. 15 However, most quantitative surveys of potential OC users found that a majority of participants supported OTC availability. 15 18 21 24 30 Slightly lower but still sizeable proportions of women said they would obtain OCs OTC if available. 23 24 30 Ease of access, convenience, privacy and time saved from clinician visits for prescriptions were the main benefits women anticipated from OTC availability. 13 16 18 30 However, across studies, participants noted concerns about cost, continued use of other preventive screening options (eg, for Pap smears, pelvic exams, clinical breast exams and sexually transmitted infections) and the safety of such access, particularly for young people, first-time pill users and women with medical conditions. 13 16 18 19 23 30 31

Healthcare professionals from France and the USA, particularly medical doctors, voiced moderate to low support for OTC availability of OCs, often citing safety concerns, OC efficacy, concerns about correct OC use or missed examinations for medical contraindications. 17 28 35 Providers generally supported making POPs available OTC more than they supported making COCs available OTC. 26

Pharmacy access

Among potential or current OC users, most women were in favour of pharmacy access, and substantial proportions said they would obtain OCs through pharmacy access if it were available. 29 30 37 Some women currently not using any contraception said they would begin using a hormonal contraceptive if pharmacy access were available. 29 One study found that women (and pharmacists) were satisfied with pharmacist-led OC use and expressed willingness to continue seeing pharmacist prescribers. 20 While young women appreciated their traditional healthcare providers, they liked the increased access and convenience of obtaining OCs directly from a pharmacy. 37

In studies among healthcare providers, pharmacists were generally very supportive of pharmacy access to OCs, while physicians tended to be more moderately supportive. 20 25 28 32–36 Increased access to care, preventing unintended pregnancies and convenience for patients were the most frequently identified potential benefits. 25 33–35 Safety, time constraints, lack of private space in the pharmacy, increased liability and reimbursement were identified as potential barriers. 25 28 33 36 There was also concern from pharmacists about physician’s resistance to making OCs available at pharmacies 28 and concern from physicians about pharmacist’s refusal to provide services. 34

Finally, in a study of digital comments on online media articles about pharmacy access to OCs in the USA, commentators were generally positive and cited benefits including increasing access to healthcare, reducing unintended pregnancies and supporting individual autonomy, but noted these must be balanced with potential safety and logistical concerns. 27

In this systematic review, we identified four studies using comparative designs to examine the impact of OTC availability of OCs. Two studies conducted in the 2000s examined women who obtained OCs OTC in Mexico and compared them with women who obtained OCs from providers in either Mexico or the USA. The other two studies were significantly older (from the 1970s) and compared first contraceptive method users who either obtained OCs OTC from a pharmacy or drugstore or through a provider or family planning programme; the OC formulations in these studies were likely different, and women 45 years ago potentially differ from women today in terms of desired fertility, decision-making around contraceptive methods and perception/tolerance of and tendency to report side effects. While the more recent studies suggested OTC users had higher rates of OC continuation over time and fewer side effects, there was some indication that OTC users had slightly higher rates of use of OCs despite contraindications. Contraindications are an important concern; however, research has indicated that women can self-screen for contraindications fairly well using a simple checklist. 40 41 Despite the strengths of the studies included in the review, the small evidence base provides limited guidance for countries considering OTC availability of OCs.

We identified a much larger evidence base on the values and preferences of potential users, providers and the public. However, this evidence was also limited, since almost all studies were conducted in the USA. Women were generally in favour of OTC availability; healthcare providers were as well, with pharmacists expressing higher support than physicians for pharmacy access. Among both women and providers, support was generally higher for dispensation in pharmacies compared with full OTC availability, and for OTC access to POPs rather than COCs. Given the near-universal use of COCs at the times and locations where the studies included in the main review were conducted, we had no comparative effectiveness data on POPs. This is unfortunate, as POPs have been suggested as a good option for initial OTC availability, given that they have fewer contraindications to use.

An additional concern about OTC availability is that the concomitant reduced visits to clinicians may also translate to a reduction in routine preventive screening (including for Pap smears, pelvic exams, clinical breast exams and screening for sexually transmitted infections). This was not one of our prespecified PICO outcomes since such exams are not required to receive OCs per the WHO’s Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use. 42 However, the Border Contraceptive Access Study did report on preventive screening; while women who obtained their OCs from a clinic reported slightly higher rates of some screenings, both groups (OTC and clinic users) had high overall rates of reported screenings with relatively minimal differences between groups. 43 One values and preferences study also found that US women said they would continue to get screened if OCs were made available OTC, 23 although clinicians were afraid they would not. 35 These findings offer some indication that OTC access for OCs may not necessarily result in reduced use of other preventive services.

OTC availability is only one way to increase access to OCs. A previous systematic review found that increasing the number of OC pill packs dispensed or prescribed increased OC continuation, although it also resulted in increased pill wastage. 44 There are also internet-based platforms for ordering OCs, which comply with clinician prescriptions or pharmacist screening, but conduct all screenings online. 45 A modelling study found that making out-of-pocket pill pack costs low or free would increase OC use. 46 Finally, increased insurance coverage for OCs should also reduce access barriers to OC use, regardless of access point. Although moving OCs to OTC status should lead to fewer clinician visits for women, thus decreasing costs related to travel, time and other medical expenses associated with those visits, OTC access could potentially increase the cost of OCs if insurance does not cover OTC purchases, or if women are unaware that they can use insurance in OTC purchases. Insurance considerations should be explicitly considered in policy discussions of OTC availability, as insurance coverage will be particularly important for some of the most vulnerable groups, such as low-income women and girls.

Our review has several strengths, including our broad search strategy and our inclusion of both effectiveness and values and preferences studies. However, conclusions from our review are limited by the small evidence base in this area. We identified four observational studies in our main effectiveness review, from the same global region, and there may have been residual confounding in comparing OTC and clinic OC users despite some analyses being adjusted. Although there were more studies in the values and preferences review, they were also geographically limited, and many relied on participants’ responses to hypothetical questions about OTC availability. While it is challenging to conduct randomised trials of what is fundamentally a policy intervention, researchers should be encouraged to take advantage of natural experiments such as the Border Contraceptive Access Study or to study changes to policies such as those recently allowing pharmacy access to OCs in the US states of Oregon and California. Further, many countries already allow OTC availability of OCs, so policy decisions can also take into consideration the wide range of country experience in this area.

Despite the limitations of the evidence base, this review provides important information to guide policy decisions around OTC availability of OCs. This evidence has been used to inform the development of WHO recommendations for self-care interventions for sexual and reproductive health and rights in relation to OTC availability of OCs. The benefits and harms of OTC availability of OCs and the values and preferences of patients and providers found in the present review, along with a separate survey of community values and preferences and consideration of resource use, human rights and feasibility, will shape the recommendation. Additional research into outcomes critical to decision-makers where little comparative data currently exist should be done to address the gaps identified.

Acknowledgments

We thank Laura Ferguson and Nandi Siegfried for their comments on the review protocol. We also thank Johns Hopkins research assistants Rui (Renee) Ling, Kaitlyn Atkins, Priyanka Mysore, Molly Petersen and Anita Dam for help with screening the initial database search results, conducting hand searching and secondary reference searching, and duplicate data extraction. Finally, we thank Daniel Grossman and Sara Yeatman for their timely and thorough responses to questions about their studies, and the excellent comments from the anonymous reviewers who really helped improve the manuscript.

Handling editor: Soumyadeep Bhaumik

Contributors: MN conceptualised the study. CEK and PTY designed the protocol with input from JK, MLG, LG, HJ and MLN. PTY ran the search and oversaw screening, data extraction and assessment of bias. CEK drafted the manuscript, while all authors reviewed the draft and provided critical feedback. All authors had full access to all of the data (including statistical reports and tables) in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. The corresponding author, as guarantor, accepts full responsibility for the finished article, has access to any data and controlled the decision to publish.

Funding: This study received financial support from the UNDP-UNFPA-Unicef-WHO-World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP) and the Children's Investment Fund Foundation (CIFF). HRP was involved in the study design.

Disclaimer: The funders played no part in the decision to submit the article for publication, nor in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data come from published journal articles. Extracted data are available on request to the corresponding author.

- 1. Grossman D. Over-the-counter access to oral contraceptives. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America 2015;42:619–29. 10.1016/j.ogc.2015.07.002 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Bearak J, Popinchalk A, Alkema L, et al. . Global, regional, and subregional trends in unintended pregnancy and its outcomes from 1990 to 2014: estimates from a Bayesian hierarchical model. Lancet Glob Health 2018;6:e380–9. 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30029-9 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. The oral contraceptives (OCS) over-the-counter (OTC) Working Group, 2018. Available: http://ocsotc.org/

- 4. Grossman D. Over-the-counter access to oral contraceptives. Expert Review of Obstetrics & Gynecology 2011;6:501–8. 10.1586/eog.11.50 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. American College of obstetricians and Gynecologists. over-the-counter access to oral contraceptives. Committee opinion no. 544. Obstet Gynecol 2012;120:1527–31. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, 2011. Available: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org/

- 7. Kennedy CE, Fonner VA, Armstrong KA, et al. . The evidence project risk of bias tool: assessing study rigor for both randomized and non-randomized intervention studies. Syst Rev 2019;8 10.1186/s13643-018-0925-0 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. World Health Organization Consolidated guideline on self-care interventions for sexual and reproductive health and rights. Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Bailey J, Jimenez RA, Warren CW. Effect of supply source on oral contraceptive use in Mexico. Studies in Family Planning 1982;13:343–9. 10.2307/1965805 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Grossman D, White K, Hopkins K, et al. . Contraindications to combined oral contraceptives among over-the-counter compared with prescription users. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2011;117:558–65. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31820b0244 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Measham AR. Self-prescription of oral contraceptives in Bogota, Colombia. Contraception 1976;13:333–40. 10.1016/S0010-7824(76)80043-1 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Potter JE, McKinnon S, Hopkins K, et al. . Continuation of prescribed compared with over-the-counter oral contraceptives. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2011;117:551–7. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31820afc46 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Potter JE, White K, Hopkins K, et al. . Clinic versus over-the-counter access to oral contraception: choices women make along the US–Mexico border. Am J Public Health 2010;100:1130–6. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.179887 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Yeatman SE, Potter JE, Grossman DA. Over-the-counter access, changing who guidelines, and contraindicated oral contraceptive use in Mexico. Studies in Family Planning 2006;37:197–204. 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2006.00098.x [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Barlassina L. Views and attitudes of oral contraceptive users towards the their availability without a prescription in the Republic of Ireland. Pharm Pract 2015;13 10.18549/PharmPract.2015.02.565 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Baum S, Burns B, Davis L, et al. . Perspectives among a Diverse Sample of Women on the Possibility of Obtaining Oral Contraceptives Over the Counter: A Qualitative Study. Women's Health Issues 2016;26:147–52. 10.1016/j.whi.2015.08.007 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Billebeau A, Vigoureux S, Aubeny E. Survey of health professionals about the Access to oral contraception over the counter in France. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 2016;21. [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Dennis A, Grossman D. Barriers to contraception and interest in over-the-counter access among low-income women: a qualitative study. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2012;44:84–91. 10.1363/4408412 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Forman SF, Emans SJ, Kelly L, et al. . Attitudes of female college students toward over-the-counter availability of oral contraceptives. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 1997;10:203–7. 10.1016/S1083-3188(97)70086-X [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Gardner JS, Downing DF, Blough D, et al. . Pharmacist prescribing of hormonal contraceptives: results of the direct access study. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association 2008;48:212–26. 10.1331/JAPhA.2008.07138 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Grindlay K, Foster DG, Grossman D. Attitudes toward over-the-counter access to oral contraceptives among a sample of abortion clients in the United States. Perspect Sex Repro H 2014;46:83–9. 10.1363/46e0714 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Grindlay K, Grossman D. Women's perspectives on age restrictions for over-the-counter access to oral contraceptives. Journal of Adolescent Health 2015;56:38–43. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.08.016 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Grindlay K, Grossman D. Interest in over-the-counter access to a Progestin-Only pill among women in the United States. Women's Health Issues 2018;28:144–51. 10.1016/j.whi.2017.11.006 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Grossman D, Grindlay K, Li R, et al. . Interest in over-the-counter access to oral contraceptives among women in the United States. Contraception 2013;88:544–52. 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.04.005 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Hilverding AT, DiPietro Mager NA. Pharmacists’ attitudes regarding provision of sexual and reproductive health services. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association 2017;57:493–7. 10.1016/j.japh.2017.04.464 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Howard DL, Wall J, Strickland JL. Physician attitudes toward over the counter availability for oral contraceptives. Matern Child Health J 2013;17:1737–43. 10.1007/s10995-012-1185-6 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Irwin AN, Stewart OC, Nguyen VQ, et al. . Public perception of pharmacist-prescribed self-administered non-emergency hormonal contraception: an analysis of online social discourse. Res Soc Adm Pharmacy 2018. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Landau S, Besinque K, Chung F, et al. . Pharmacist interest in and attitudes toward direct pharmacy access to hormonal contraception in the United States. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association 2009;49:43–50. 10.1331/JAPhA.2009.07154 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Landau SC, Tapias MP, McGhee BT. Birth control within reach: a national survey on women's attitudes toward and interest in pharmacy access to hormonal contraception. Contraception 2006;74:463–70. 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.07.006 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Manski R, Kottke M. A Survey of Teenagers’ Attitudes Toward Moving Oral Contraceptives Over the Counter. Perspect Sex Repro H 2015;47:123–9. 10.1363/47e3215 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Nayak R, Brushwood D, Kimberlin C. Should Oral Contraceptives Be Sold Without a Prescription? An Analysis of Women’s Risk and Benefit Perceptions Regarding Nonprescription Birth Control Pills. Journal of Pharmacy Practice 2005;18:479–85. 10.1177/0897190005280522 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Norman WV, Soon JA, Panagiotoglou D, et al. . The acceptability of contraception task-sharing among pharmacists in Canada — the ACT-Pharm study. Contraception 2015;92:55–61. 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.03.013 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Rafie S, El-Ibiary SY. Student pharmacist perspectives on providing pharmacy-access hormonal contraception services. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association 2011;51:762–5. 10.1331/JAPhA.2011.10094 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Rafie S, Haycock M, Rafie S, et al. . Direct pharmacy access to hormonal contraception: California physician and advanced practice clinician views. Contraception 2012;86:687–93. 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.05.010 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Rafie S, Kelly S, Gray EK, et al. . Provider Opinions regarding expanding access to hormonal contraception in pharmacies. Women's Health Issues 2016;26:153–60. 10.1016/j.whi.2015.09.006 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Vu K, Rafie S, Grindlay K, et al. . Pharmacist intentions to prescribe hormonal contraception following new legislative authority in California. J Pharm Pract 2017;897190017737897. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Wilkinson TA, Miller C, Rafie S, et al. . Older teen attitudes toward birth control access in pharmacies: a qualitative study. Contraception 2018;97:249–55. 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.11.008 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Shah MA, Shah NM, Al-Rahmani E, et al. . Over-the-counter use of oral contraceptives in Kuwait. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 2001;73:243–51. 10.1016/S0020-7292(01)00375-7 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Yazd NKK, Gaffaney M, Stamm CA, et al. . Physicians and pharmacists on over-the-counter contraceptive access for women. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31:S342–S3. [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Grossman D, Fernandez L, Hopkins K, et al. . Accuracy of self-screening for contraindications to combined oral contraceptive use. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2008;112:572–8. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31818345f0 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 41. Shotorbani S, Miller L, Blough DK, et al. . Agreement between women's and providers' assessment of hormonal contraceptive risk factors. Contraception 2006;73:501–6. 10.1016/j.contraception.2005.12.001 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]